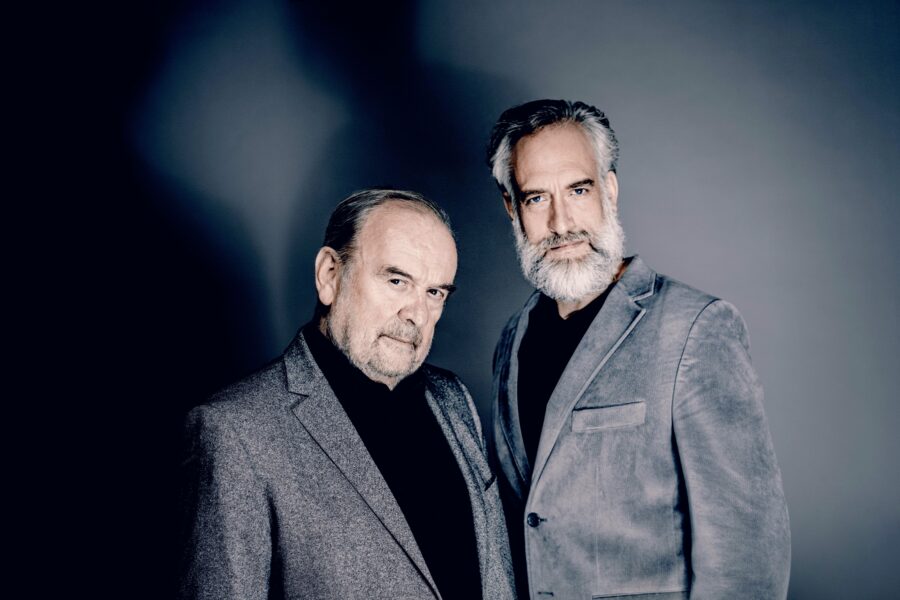

Schubert, Mahler, Brahms, Schumann, and Liszt are names known and celebrated within the world of lieder; Christian Immler and Helmut Deutsch are hoping to add a few more to the list. The celebrated bass baritone and collaborative pianist are set to release Be Still My Heart (Alpha Classics) featuring the music of Robert Gund (1865-1927) and Wilhelm Grosz (1894-1939), two composers whose oeuvres have been largely overlooked. This isn’t the first time Immler and Deutsch have highlighted the work of unknown composers. The pair released Hidden Treasure (BIS Records) in 2021, which shone a light on the work of composer Hans Gál. At the time of its release Immler wrote in Gramophone that “(r)eading through and rehearsing music which hasn’t ‘become sound’ for more than a century is for me a powerful combination of curiosity, pioneer spirit and obligation. One is indeed living history!” That spirit of exploration continues with Be Still My Heart, which, amidst its thirty-three tracks, hosts several world-premiere recordings – not a small achievement given the sheer volume and consistently high quality of its respective composers’ output.

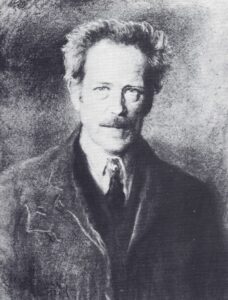

Portrait of Robert Gund by Ludwig Michalek, around 1921. Private collection.

Swiss-born Gund (who used the more French “Gound” for a time before changing it in 1916) enjoyed an illustrious career in Vienna, where, over the course of three decades as a singing and harmony teacher, he built a considerable reputation as both an educator (Alma Mahler was among his students) and composer. He created many works (especially songs) – but also destroyed many, including a symphony, a piano concerto, and an original opera. German writer/musicologist Ernst-Jürgen Dreyer contributed album notes to a 1986 Jubilate vinyl release of songs featuring soprano Franziska Hirzel and pianist Ilona Sándor, and noted that “(f)ew people … suspected that the modest and amiable man known in all salons, father of a family rich in sons, pianist in countless chamber music pieces, sought-after song accompanist and organiser of ‘music jours’ and ‘student productions’, not only had something to add to the songs of the moderns as a composer, but that he surpassed them with genuine song talent.”

In his opening for the liner notes to Be Still My Heart, multi-award-winning producer Michael Haas (who is also the co-founder of Vienna-based exil.arte) quotes a 1905 essay by critic Julius Korngold that savages the contemporaneous state of Viennese lieder while notably singling out Gund for praise; Haas goes on to weigh the reasons behind Gund’s gradual disappearance in music, noting his unique position in Vienna at that time:

… his compositions, as confirmed by Julius Korngold, presented a reliable oasis of stability, offering beauty and inventiveness within the bounds of received convention. Unfortunately, “received convention” was not a priority in the early days Viennese Modernism.

(Michael Haas, Be Still My Heart, 2025)

Wilhelm Grosz, 1927 © Georg Fayer; ÖNB, Bildarchiv Austria

Wilhelm Grosz, twenty-nine years Gund’s junior, was born in Vienna and schooled by a wide range of composers, Franz Schreker among them. Grosz would go on to become the artistic manager of the Ultraphone Gramophone company in Berlin before leading the Kammerspiele Theater in Vienna, though he was forced to flee Austria in 1934. After a short stay in the UK, the composer (who used a number of pseudonyms) moved to New York with plans to continue on to Hollywood, joining other exiled European artists – but he died of a massive heart attack in 1939. His considerable output includes orchestral works, chamber music, film scores, music for two ballets, and three operas; his work would go on to be covered by a range of artists including Frank Sinatra and The Beatles. Haas contextualizes the presence of Grosz within a Viennese progressivism that is more wide than it may first appear, observing the composer’s “metamorphosis from Viennese fin de siècle, to songs for German cinema before teaming up with Billy Kennedy in London under the pseudonyms Will Gross, André Milos, Hugh Williams or Hugh Grant for hits still popular today such as “Isle of Capri” or “Harbour Lights.””

Be Still My Heart celebrates this range by offering a wide array of sounds and experiences. The album, recorded in early 2023 at Munich’s BR-Funkhaus, conveys a deep respect for history alongside a passionate embrace of innovation. With texts by a wide range of writers (including Hesse, Brentano, Morgenstern, Lenau, and Rilke) the album skillfully explores aspects of love, loss, longing, memory, and identity, with a keen sensitivity belying its academic roots. Be Still My Heart is three-dimensional, textured, real, raw, cutting – rooted in a near-forgotten history indeed, but utterly, unmistakably alive with a palpable and timeless passion.

The album is also a showcase for Immler’s intense timbral shading and Deutsch’s intuitive, poetic playing; their interplay, so clear in works like Gund’s “Julinacht” and “Nachts”, or Grosz’s “Helle, sommerliche Nacht” and “Schicksal”, serve to highlight the pair’s clear creative chemistry and near-psychic musical connection. My recent exchange with Christian Immler and Helmut Deutsch touched on forgotten and found histories, the challenges of unknown work (not least in playing it), the joys of long-term collaboration, and what it means to be on the same page in terms of artistic curiosity.

“A Distinct Musical Language”

“A Distinct Musical Language”

Why do you think Robert Gund’s work is so largely unknown now?

HD It’s quite unbelievable that his work is so completely forgotten. Here is a man who had performed his own symphony in the Vienna Musikverein, who was close to Mahler and before that to Brahms; he was really in the music world of Vienna in those years. But we don’t know what happened.

CI We are baffled by his music being so unknown, but there are a few theories. Helmut and I have been like detectives through the years, finding and recording unusual repertoire alongside well-known works; in those instances we were usually lucky if we got ten good songs from our investigations – but Gund wrote hundreds of songs, many of them in absolute top quality, so we really had a hard time choosing what to feature on this album – I think that’s the best compliment we can give him.

Halls will often skew their programming toward box office, especially now – “We know we can sell tickets to star names and/or Schumann/Schubert/Mahler” – and everyone else is ignored – maybe that thinking played a role also?

HD Well that’s right, and it’s worth noting that amidst those names Gund really cultivated his own language – a distinct musical language – from them; some parts of his work remind me of Brahms a little bit, but there are things in his writing which you cannot compare easily to any other composer of his time.

Yet he destroyed some of his early works, didn’t he?

HD Yes, in his very young years, he had written a symphony and a piano concerto – which he burned.

CI I wrote to the library of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Society of Friends of Music) in Vienna, and I really tried to learn more. I mean, for that kind of a destruction, you don’t have to only destroy your piano part, you have to destroy all the orchestral parts – and absolutely everything seems to be really, really gone. So he really meant it when he burned his own work – but it cannot have been bad if it was premiered at the same time as Zemlinsky’s symphony, right?

Zemlinsky was just one of his many music contacts, is that right?

CI Yes – along with composing, Gund had been the archivist of the Tonkünstlerverein association founded by Schoenberg in Vienna, and he had been Alma Mahler’s counterpoint teacher; he had also played four-hand piano with Brahms! He had all these people on what you might call speed-dial now. Along with these connections Gund was one of the first musicians to promote and actually present lecture-recitals in which he would discuss his research on the complexities of thematic connections in music – and he was twice married to a singer, so he had easy access to interpreters. But I think at heart he was a private person, and he just didn’t like the craziness of what an international career would demand. I met Gund’s grandson, and the more we spoke, the more it seemed as if this was true. Gund, as a composer, seems to have been extremely private.

Natural, Elegant, Evocative

So how would you characterize Gund’s writing then?

CI The quality of his writing is phenomenal! And – I don’t say this lightly – I am hopeful, if not convinced, that more people will be performing his songs now. I have had so many young students already say, “I love this, where can I get the music?” and I tell them: it’s printed. The majority of his lieder were printed in his lifetime, and they are available now; you don’t have to go to any society and get the manuscripts. It’s all printed, everything is out there. And this album with Helmut feels like it was something which was meant for us to do.

What were the unique challenges of not only choosing which pieces to play, but then perfecting and recording them?

HD We had difficulties making selections because there are only so many minutes you can have on a CD. When we first selected the songs we liked, we went far over the running time – so we had to edit, and it was really very hard for us to say goodbye to so many wonderful works. There is much more to discover of Gund than is even on this record.

CI The main thing we wanted was to have a nice mix; some of the songs make use of unique metres, like 5/4, but Gund uses the time in such a refined way that it just lulls you in. And I think Helmut can confirm that some composers try to get the piano accompaniment right, but Gund comes from a more pianistic side already – he was lucky to be married to singers who probably also had their influence on his writing – but the piano parts are incredibly interesting. So whenever, as a singer, I had the feeling that I needed a little injection of energy, it was right there. Gund uses very simple things, things that, in my opinion, only a master composer can apply in such a way. His writing feels very natural, very right, simple but elegant, and very evocative and realistically idiomatic for the actual instrument, whether voice or piano.

“A Rollercoaster of Musical Styles”

So why Gund and Grosz, together?

CI To start at the beginning: Helmut actually found a book about Robert Gund. That was the initiative. I think; you stumbled across it by chance – correct me if that’s not right, Helmut?

HD It was in Bonn, in a bookshop; there were two books there for five marks – so it was a long time ago indeed – they had Gund’s musical life only, and an appendix with 40 songs. I tried to encourage my former students in Munich with them, and some of them performed a few of the works – but It needed a person like Christian to conduct more research and to find all his other songs. We found out that there is much, much, much more. They both have the connection to Vienna, of course…

CI Yes, the combination with Gund and Grosz was done with reference to very different eras for Vienna composers; I also wrote part of my doctorate about Wilhelm Grosz and the recital scene in Vienna between the two wars. Gund and Grosz meet kind of right in the middle of an era in flux; one person is kind of tapering off and the other person is just emerging. Obviously the style of each is different, but having them both on one recording gives you a little rollercoaster of musical styles, and also a choice of poems; then it ends on Grosz’s English-language songs, which are much lighter.

What makes Grosz’s writing unique?

CI He had an incredible gift for melody, in my opinion, his sense of melody is just so sticky. We mention it in the booklet also, that his work has been covered by the likes of Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, The Beatles.

HD Initially with the early Grosz songs, I wondered: could I, maybe for a few minutes, be 30 years old again, just to find out whether it’s just my current age making these works difficult, or if they are really so complicated? A lot of parts in these early songs he wrote are on three systems, or, not only three systems – Debussy used this kind of writing also – but most of the chords Grosz writes for both hands have ten voices. And there are a lot of really complicated things in terms of where to put this middle line – in your right hand and in your left hand. Despite my age, I would consider myself not bad at sight-reading…

CI You are the best!

HD … but you could read one chord at one point, and you needed three or four seconds there to figure out the next chord; then the next and the next. In the end, it should be a more or less flowing tempo. After ten days, I was really very close to saying, “Christian, I’m very sorry, I give up.” But I didn’t give up. Now, after a while away from Grosz’s songs for a bit, I look at one of them and that feeling starts again – this can also be extremely difficult. So while Gund was certainly a very good pianist and did write very effective things on the piano, they are not difficult by comparison with Grosz.

CI The feeling of finding music like this… I mean you have an idea of its sound if you look at the music of the time, but there is really no comparison either. You don’t feel any influence by Brahms – maybe there’s a little bit in some songs – but there is no influence by Mahler. There are also no comparisons with recordings as with these other composers, like “This is the best recording of this and that” – when you are making the 250th recording of Winterreise, for example, you can scan generations, but here, you have to find out together, with a musical partner, and this was a fascination.

Discovering Together (With Wine)

Helmut Deutsch (L) and Christian Immler (R). Photo: Andrej Grilc

How has the working chemistry between you changed through the years? And do you, together, feel like ambassadors for these little-known lieder composers?

HD It’s thanks to these composers that the quality is, very much, in the music. And we have, if I may say so, Christian, the same taste.

CI This is very true!

HD It’s always a bad signal if you have to have a lot of discussions about a tempo, about a rubato or the like: “Why do you do this? I would like to go straight forward and you are hesitating.” I can’t remember any discussion of this kind working with Christian. One has to be very thankful to have a partner who feels the same.

CI Yes. I mean, it evolves from rehearsal to rehearsal, but talking about tempo is for me, very annoying. A purely music-making and non-verbal rehearsal is often more effective! The only thing we discussed, really, was which white wine to put into the fridge for dinner – that was important! But the prolongation of our curiosity is something I’m very fortunate to share with Helmut; it’s been a long collaboration already. And I don’t know any other pianist with whom one can have so much fun, just sitting at the piano and trying things out. It is incredible to examine repertoire like this.