First, the obvious: yes, Michail Jurowski is the father of conductors Vladimir and Dmitri, and vocal coach and pianist Maria. He comes from a long line of musical talent: his own father, Vladimir Jurowski (1915-1948) was a conductor and composer, and his grandfather, David Blok (1888-1948), was a conductor, film composer, and the first head of the State Orchestra of the USSR Ministry of Cinematography. Both Jurowski and his sons have conducted the work of his father (whom his first-born son was named after), including the sumptuous ballet suite Scarlet Sails (1942), based on the 1923 Alexander Grin novel of the same name.

There are many memories one may hold dear with relation to a particular recording; some of my fondest are tied to Michail Jurowski’s 2017 recording of Moses, by pianist-conductor-composer Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894). Constructed around eight scenes and based on episodes from the biblical book of Exodus, Rubinstein composed the piece between 1884 and 1891, using a libretto by Salomon Hermann Mosenthal. The vocal work (or “geistliche Oper” – sacred opera – a term Rubinstein coined himself) follows the biblical story of the prophet Moses from his childhood through to being given the Ten Commandments and handing authority to Joshua. It is long (over three hours), but it is fascinating, a deeply evocative aural journey, with an abundance of rich vocal writing weaved throughout a plush neo-Romantic score. Sonically familiar, and yet not, and filled with paradox: epic and yet intimate; religiously specific and yet totally secular, its writing is immediate and yet over-arching, broad, a strangely symbolic expression of the human relation to the divine, one that is graspable and yet distant, personal and yet universal. There are clear musical references backwards (to works by Balakirev and Mussorgsky), forwards (Zemlinsky and Henze), and mostly near-contemporaneous, with the sounds of Wagner, and more specifically, the writing of Tannhäuser (1845) and Lohengrin (1850) given clear nods.

With such a rich integration of sounds, a dense score, and its need for a very large orchestra, the work was never presented during Rubinstein’s lifetime, or for a long period thereafter. A planned presentation in Prague in 1892 fell through when the theatre (then Neues Deutsches Theater; later Státní Opera) went bankrupt; public taste had shifted too, and Rubinstein’s passing in 1894 left the work in relative obscurity – until the efforts of Russian conductor Michail Jurowski, who spent years undertaking careful research and restoration of the score. Moses was given its world premiere in Warsaw in October 2017, with the Polish Sinfonia Juventus, the Warsaw Philharmonic, and Artos Children’s choirs. Featuring a stellar cast (including tenor Torsten Kerl, sopranos Chen Reiss and Evelina Dobraceva, and baritone Stanislaw Kuflyuk in the title role), the recording (released via Warner Classics) is as much a distillation of late-19th century musical thought as a call for broader contemplation; here the creative is personal, and the personal is certainly creative. Jurowski’s refined management of these immense orchestral forces feels intimate, as if he’s talking to the divine himself, whether through voices or violins; such an approach underlines the epic yet intimate writing, and acts as a powerful symbol bridging sound and spirit.

Such creative integration is what Michail Jurowski (b. 1945) excels at, a gift discovered early on, and shown through numerous recordings and live performances. Having studied conducting in his native Moscow under conductor Leo Ginsburg and musicologist Alexey Kandinsky, Jurowski went on to assist the legendary maestro Gennady Rozhdestvensky at the National Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra of Moscow, and conducted regularly at Stanislavsky Theatre and Nemirovich-Danchenko Moscow Academic Music Theatre, and began conducting at the Komische Oper Berlin (then in East Berlin) in 1978. In 1989 he accepted a permanent post with the Dresden Semperoper, departing the Soviet Union shortly thereafter to live permanently in Germany. Since then, he has held numerous positions, including Chief Conductor of Leipzig Opera, Principal Conductor of Deutsche Oper Berlin, General Music Director and Chief Conductor of the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie, and Chief Conductor of WDR Funkhausorchester Köln. Between 1998 and 2006 Jurowski was Principal Guest Conductor of the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin. He has also made numerous guest appearances with orchestras around the world, including the Leipzig Gewandhaus, Dresden Staatskapelle, the St. Petersburg Philharmonic, the Oslo Philharmonic, the Bergen Philharmonic, MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra, Königlichen Kapelle Copenhagen, the Buenos Aires Philharmonic, Orquestra Sinfónica do Porta Casa da Música, the São Paulo Symphony, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, and has led a myriad of opera productions and ballets in many prestigious houses, including Teatro alla Scala, Bayerische Staatsoper, the Bolshoi, Opernhaus Zürich, and Malmö Opera. He has also led televised concerts and radio recordings in Oslo, Norrköping, Berlin, Stuttgart, Cologne, Dresden, and Hannover, and won the German Record Critics’ Prize in both 1992 and 1996; five years later, maestro received a Grammy nomination for his recording of orchestral works by Rimsky-Korsakov done with the RSB. In 2018 he was a recipient of the Accademia Internazionale “Le Muse” award, presented in Florence, recognizing his significant contributions to culture.

Photo: T. Müller

Jurowski made his long-awaited North American debut in May 2019, leading the historic Cleveland Orchestra in a programme featuring the music of Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich; the concert was met with great success, and, as you’ll read, meant a great deal personally to the maestro. More recently Jurowski completed a series of concerts in Sweden, opening the season of the Norrköpings Symfoniorkester, with whom he has enjoyed a long and happy working relationship; the well-received concert featured works by Mozart, Tchaikovsky, and the world premiere of a new double concerto for violin and cello by Russian composer Elena Firsova, a performance which featured violinist Vadim Gluzman and cellist Johannes Moser as its soloists.

Norrköpings and Jurowski have numerous live performances and impressive recordings in their shared history including a 2015 release (via cpo) of Vladimir Jurowski’s Symphony No. 5 and Symphonic Pictures: Russian Painters. The conductor has also made numerous recordings of the work of Shostakovich, stellar as much for their intense musicality as for their emotional immediacy. A 2017 album of live recordings (Berlin Classics) with the Staatskapelle Dresden from the International Shostakovich Festival in Gohrisch won the German Record Critics’ Prize, with the conductor also being formally awarded the Third International Shostakovich Prize by the Shostakovich Gohrisch Foundation that same year. Along with the famed Russian composer, the music of Prokofiev, Grieg, Tchaikovsky, Meyerbeer, Rangström, and Khachaturian (another family friend) constitutes a good part of his discography.

via cpo

A cornerstone of my own musical exploration is a 1995 recording (released via cpo) of Symphony No. 2 and Symphony No. 7 by Georgian composer Giya Kancheli, with Jurowski leading the Rundfunk Sinfonieorchester Berlin. The alternating moments of tenderness and dread are handled with deft elegance; Jurowski brushes the sonic tapestry of textures between strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion, with skill and precision. One moment, shimmering, glittering, and gleaming, the next, piercing, gripping violence. Few conductors, I think, understand Kancheli’s music better; Jurowski carefully modulates the blinking, winking silences in a way that makes one rethink orchestration and resonance within such a rich sonic universe; if the composer shows you an ocean, Jurowski asks you to dip in a toe, then a leg, and then… any charges you can’t swim suddenly don’t seem very real. Jurowski has this gift, for making you understand connection, and your role in making them, in real time. Such expertise highlights, once more, the beguiling trinity of spatial-sensual-spiritual in understanding and appreciating music, an integration I strongly suspect transferred more than a bit onto his offspring.

Among his many engagements this season, Jurowski is scheduled to lead Boris Godunov at Bayerische Staatsoper (a revival of a Calixto Bieito production from 2013) with a stellar cast featuring Dmitri Ulyanov, Ekaterina Vorontsova, and Brindley Sherratt; he’s also returning to La Scala for a revival of Swan Lake. This Thursday he’ll be on the podium for a concert with the St. Petersburg Philharmonic featuring the music of Beethoven and Penderecki. Just as you’d expect, Jurowski is as much of a great storyteller with words as with music. Ever kind, ever patient, with a big laugh and warm, open facial expressions, he was hugely generous with time and energy, his words (about meeting Stravinsky and Shostakovich, about doing the same programme several days in a row, about the role of compromise in dealing with repressive governments) inspiring many ruminations long past the hour we spent conversing. I remain immensely grateful for such an exchange with such a special person.

Photo via IMG Artists

You had your American debut with the Cleveland Orchestra in May (2019); how did it go?

I felt it was fantastic! It was a huge success. We got standing ovations, and it was a big present for me, especially after a long time waiting.

Too long!

Well you see, better late than never!

Did you notice any differences between American audiences and European or Russian audiences?

In general, no. It is different between a prepared audience and one absolutely fresh, yes – but it can be this way in Vienna, in Berlin, location is not even the question. I met a really very good, very prepared, and highly cultured public. It was lovely!

It has to be said: the Cleveland Orchestra has a very long and very big tradition. I first heard this orchestra in the 1960s in Moscow with George Szell, and I remember these concerts very well — it was one of the most powerful feelings in my life, to experience such an orchestra and conductor. So when we met, the orchestra and me, it was within the first five minutes we immediately understood each other. The programme was fresh to the orchestra — well, not the Tchaikovsky violin concerto – but the Eleventh Symphony of Shostakovich (1957), which is today rather seldom presented onstage. It is a symphony which had its influence from Hungarian revolutionary events of 1956, but Shostakovich’s special talent and his genius, was that he referenced, in his compositions, the problems of the whole world. The vision of violence, of death, of life, everything, not in the biographical sense in one or other way, but in the intonation. This is really music from heart to heart, and I can say it was truly so in Cleveland.

I had the possibility, with these concerts, to speak with the public, for about forty minutes. We spoke about my personal experience with Shostakovich (1906-1975), and some related biographical moments. It was in parallel with violinist Vadim Guzman, who brought his violin, on which was premiered the Glazunov violin concerto. That was an incredible but historical instrument he used! So, to answer your original question, yes, I was very happy to be there. I had not only the possibility to make music together with this orchestra but also to have contact with the American public. I had the feeling I was in paradise.

How much do you think music can contribute to breaking down barriers — cultural barriers, political barriers, emotional barriers?

Music, first of all, is notes. It is just notes. And it is really seldom we can find the direct connection between historical or political events, so music, in general, is a retrospective art, or an art for the future: what I felt by some fact of life; or, what I want to wish for humanity – and so on. The Tenth Symphony of Mahler (1910), for instance, connects with the event of the letter of architect Walter Gropius to Mahler’s wife – Mahler understood his wife was not with him; it was a shock, and from this shock began the composing of the symphony, and really the climax of the first movement. It’s a question we know the answer to here: what was this input (the source of inspiration)? We know it. For Shostakovich, in another example, one of his most famous pieces is his Seventh Symphony (1942). It was composed during the terrible blockade in Leningrad during the war, but you see, the material of the first movement was in Shostakovich’s head before the war. And for Shostakovich, violence does not have a national form; violence is violence, it is more than geographical. So this is one of the reasons why, for example, the Seventh Symphony has such success today. This season I will conduct it in Italy; I’ve done it almost every year somewhere, and this year it will be in Sicily. People understand its power, no matter where it is played.

Photo: T. Müller

In an interview earlier this year you said you originally wanted to be a film director, and I wonder how much cinematic sense you bring to what you conduct, because some of your recordings are strongly cinematic in nature.

Your comparison with cinema… yes, maybe this observation is right! I try to blend music with cinema and theatre. I am also a theatre (opera) conductor, after all. I look behind, and I remember in my childhood: I didn’t want to be a musician, because my father was a composer. I wanted to be a theatre director! Our house was open for contact with really fantastic artists of the time – among our guests was not only Shostakovich, but also (violinist) Oistrakh (1908-1974) and other great musicians. My father had very regular contact with various artists in cinema as well. In the West the names of Soviet directors are not so important, except maybe for Dziga Vertov or Sergei Eisenstein, who were very big directors of the 1930s; of course society was absolutely closed then, but I can tell you that such directors as Rolan Bykov (1929-1998), Mikhail Romm (1901-1971), Sergei Gerasimov (1906-1985), and other Soviet directors – they were regulars, and all top-quality in terms of their being recognized artists of world cinema.

So for me, it was a very important moment, to be able to be around them, and it led to asking myself such questions: “What is moving conflict?” and “How do I find the right inputs as to what music is used here?” Music is an abstract art; it is only notes. I just try to understand what happens with these notes, but it means I compose, in a sense: the changing of effects, the language of music, this moving between con moto and sostenuto, the idea of musical structure. Musical form can be only realized during live performance; music is when we play and in this case, form, structure. It’s what happens, I hope, when I bring the right form to the public during various pieces.

The other side, from my personal kitchen, is from a time when I had a big friendship with the Tonkünstler Orchestra (Austria). The traditions of this orchestra are to repeat one programme through seven or eight concerts, so with this programme, I had such work. It was, as usual, a series of concerts on a tour, including two or three in the Musikverein (Vienna). It was sometimes rather difficult to repeat like that, seven or eight times, the same composition, night after night.

That seems strenuous!

Yes, it was. For a moment I decided to change my understanding of this programme – what I must feel, what I must think, just come with this Shostakovich work that I had to conduct seven days in a row without pause. This symphony, as with almost all of them, needed very high tension, and after seven concerts I felt myself … well, the best thing was to go fishing afterwards; I was absolutely empty and terribly tired. I was fine up to the second day or after that, but before me was three or four next. To your question about cinema, it was like this: that night I understood if I go by plot, so to say, by events, every time, and prepare myself for some of the score’s climaxes, or relate them to some moments which in life happened, unfortunately, then for me it must be personally not only a pleasure to make big music, but also very interesting. And from this moment, the door for this sort of action and understanding, of what happens in music, was opened.

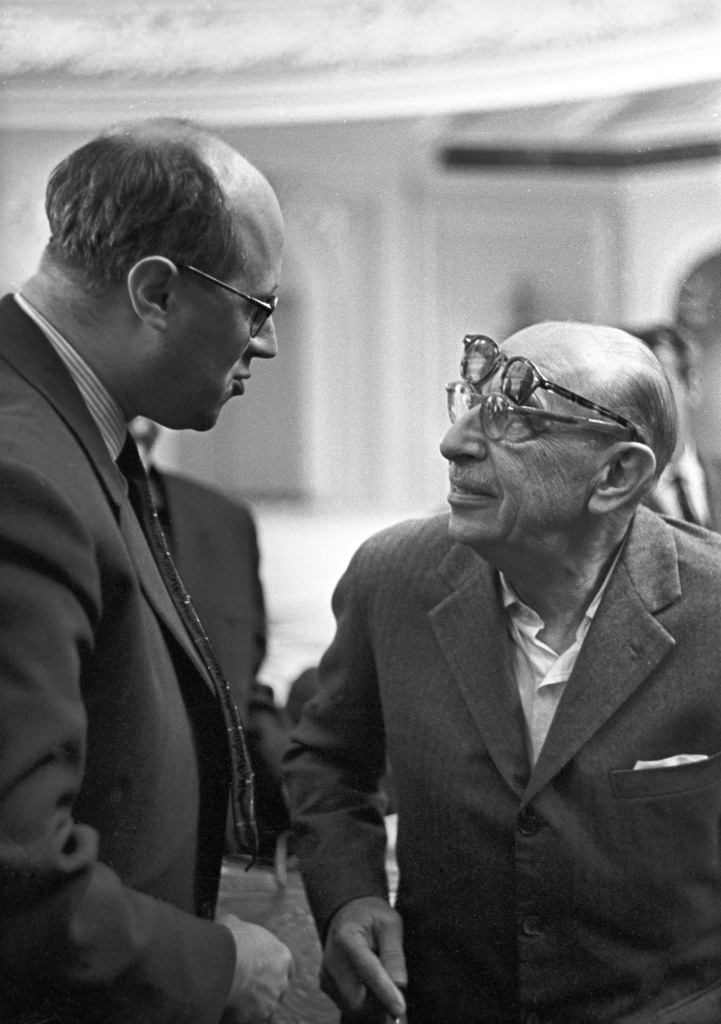

Composer Igor Stravinsky and cellist Mstislav Rostropovich in Moscow, September 1962. (Photo: RIA Novosti archive, image #597702 / Mikhail Ozerskiy / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

You observed in that same interview that Stravinsky would “imbue the music with a human meaning.” What did you mean?

I had the opportunity to speak with Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) in 1962. He was in Moscow, playing there, it was his visit together with Robert Craft, his first time visiting Soviet Russia. He had received special permission to visit. Stravinsky not only conducted – he was a very good conductor – but also he had some meetings with Soviet composers. My father took me to one of these meetings. Standing there, about four metres from him, he asked me what I wanted to compose. I was sixteen years old; I told him I wanted to be a conductor.

“And what do you want to conduct?”

At that time we were allowed to know Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring) — I had the score with me. I told him, “Of course, Sacre du Printemps!”

“Why?” he asked.

“It’s such a beautiful piece, but it is also so difficult.”

“It’s not difficult,” he said, “everyone and his dog can conduct it.”

I remember this. He was highly intelligent when he spoke. It was incredible. I remember some of the musicologists asking him about his autobiography, things like, “In your conversations with Mr. Craft, what is true and what is not true?” And Stravinsky said, “Truth is only music; don’t believe the words.”

Stravinsky gave us very different pieces, very different ideas. He had personal experience with Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky, but his expression became different from the Russian music of Firebird, Petrushka and of course, Sacre as well. He was composing these anarchic, fantastic things, destroying all worlds, with these fantastic harmonies in his new classics. He’s a very important person of the 20th century and I would compare him with Picasso, because stylistically, he is like Picasso: he changed a lot during his life. Where is the real Picasso? We don’t know. And we don’t know where the real Stravinsky is either, but he is real, always.

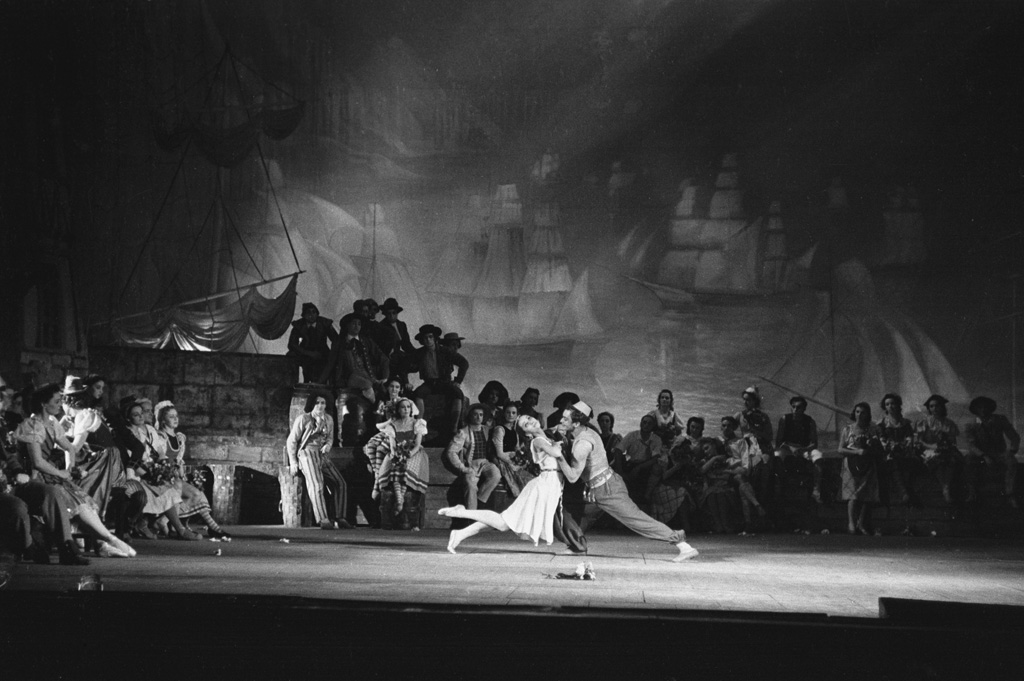

Olga Lepeshinskaya as Assol and Vladimir Preobrazhensky as Arthur Grey in a scene from Vladimir Jurowski’s ballet Scarlet Sails, staged at the State Academic Bolshoi Theater of the USSR, December 5,1943. (Photo: RIA Novosti archive, image #941010 / Anatoliy Garanin / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

How does that quality of ‘the real’ translate in leading pieces by your father? Or in watching your sons conduct his works?

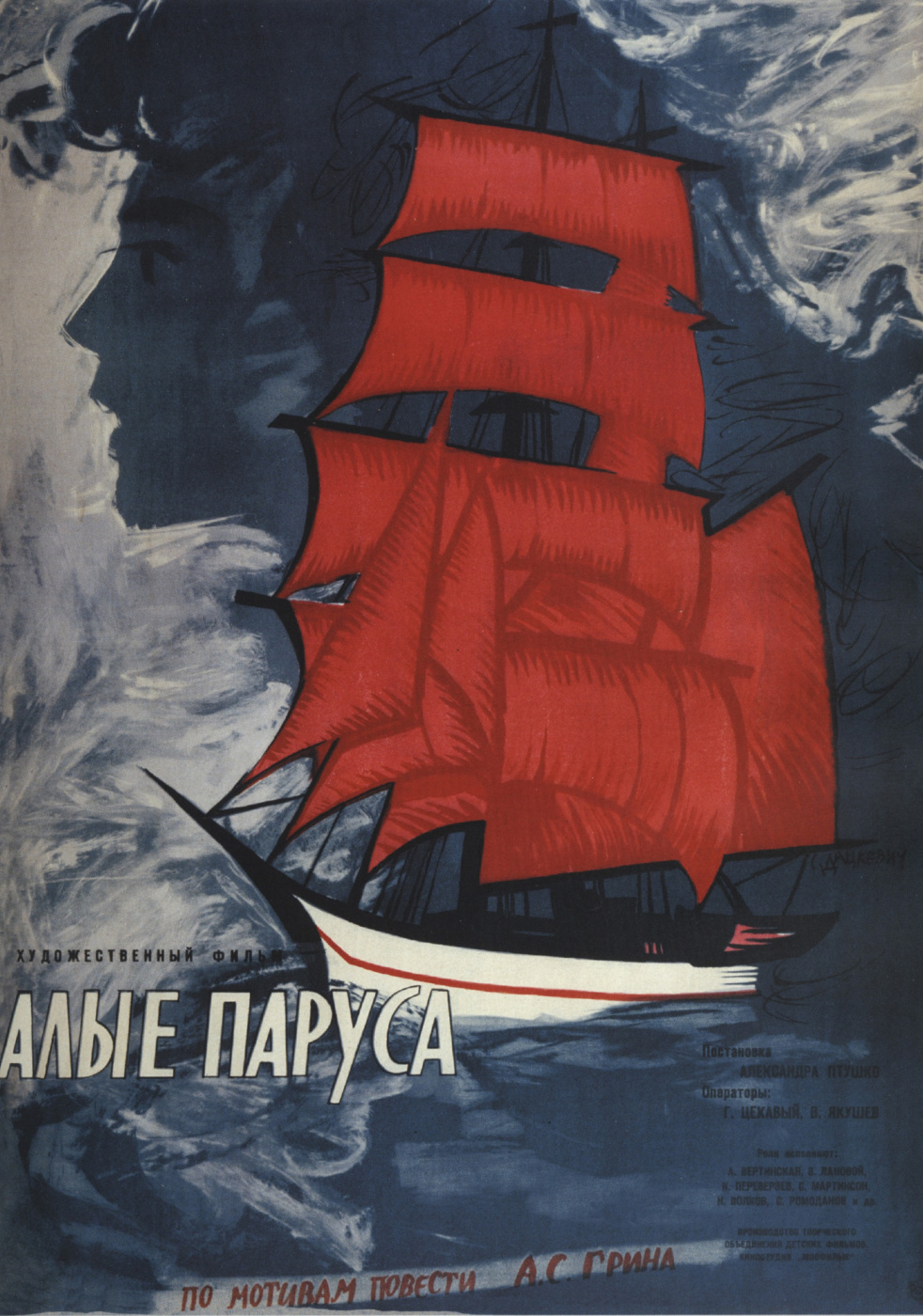

If you speak about my father, I find him one of the outstanding composers of his time. He died very early – he was only 56 years old – and he was not in the music mainstream. We are Jews, the whole family, so within the Soviet Union, our stock line was always, as you might say, “ten kilometres behind others” – that is how it was. His work was not forbidden though, he had a very big success with the public, but he had no help from any of the organizations at the time to have developed that success. His ballet Scarlet Sails, after the romantic novel of Alexander Grin, was played for fourteen years on the stage of the Bolshoi – it was on during the Second World War. At the time of the war there was a deep hunger for the high romantic, and a very, so to say, Christ-like idea about the inferno in life and paradise in future. In this sense (the ballet) captured Grin’s theme, that patience of the soul has to be without any orders – then Captain Grey will come with a big ship, with red sails, and take one and one’s life away to better things. Shostakovich wrote a highly positive critique to this ballet in the central press.

Movie poster for the 1961 film Scarlet Sails (directed by Alexandr Ptushko) based on the novel. (Photo: Mosfilm)

The music of my father was high romantic. I cannot say he was like some other composers. His music was tonal music, and with a very positive feeling, but step by step, his own view of life became worse and worse; belief for him was very difficult and he was ill. There were a lot of difficulties in his life. During the war there were difficulties experienced by everybody, but after the war it was sometimes very difficult for him indeed, and some of those challenges were very personal.

I’m very happy all of us – Vladimir and Dmitri and me – opened the pages of his music. My recordings of his work were met with good press, and there were very successful concerts in Moscow this year, by Dmitri – with his symphonic poem Otello; and Vladimir’s concert with the Moscow students, he had a big success with Scarlet Sails. And my concert also, with the Fourth Symphony, which was again with students of the Moscow Conservatory. The time for my father’s music is coming, and it will not be for my father’s own name alone.

This relates to the atmosphere after the war in the Soviet Union and especially in Moscow: there was an absolutely fantastic group of composers, really very high-rate composers, not only Shostakovich, who I think was a genius, but also Khachaturian, Karayev, Mieczysław Weinberg, and others whose music now also is getting attention. I knew those composers, of course, including Weinberg (1919-1996), and now I’m making a CD of his music with Staatskapelle Dresden (here Jurowski holds up an immense score with markings – ed.); this is now what I work on, which I enjoy. All the other pieces are already ready — the Clarinet Concerto, for instance. I hope by the end of this year the album will be ready to release.

It’s encouraging to see the work of these composers being more frequently performed and recorded.

It’s very good! I must say, I, personally think society today has a lot of clichés that really close off the connection with the high-level composers of that time – the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s. In this time, Soviet music was not only Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998), Sofia Gubaidulina (1931), Edison Denisov (1929-1996) and so on – whose work I played a lot. Granted, it was not a very big group of composers, but there were enough that any musical culture would be proud to have them. I met practically all of them. After our immigration, I had no contact, not only with these people – most of them died – but the world in the West opened up such big doors for me, and I had a free feeling from different sides.

Now I’m almost 74 years old, and I don’t think I ever lived with a view that looked only behind – but I also understand that not everything today is for the development of the soul, so I try with all my forces to compensate for that, and I’m very glad that Vladimir has done practically the same. It’s in a bit of a different form, but he has more possibilities than I did. He is now at the age for doing that – well, he is a little older than I was when we jumped to Germany. At his age right now is precisely when I really began my world career, incredibly.

It was like a whole second life for you to start over the way you did.

In this form, with family and children and career and all the various factors – yes.

Leading the Norrköpings Symfoniorkester in October 2019 with violinist Vadim Gluzman and cellist Johannes Moser. (Photo: Calle Slättengren / Norrköpings Symfoniorkester)

What role do you think authenticity plays? You mentioned clichés and the development of the soul; it seems like within the cultural realm now authenticity is increasingly difficult to find.

I suppose that it depends from what point of view you perceive such things. In the famous and very good Pushkin work Little Tragedies, within the story of Mozart and Salieri, there is a whole tragedy from the phrase, “There is no justice on the earth, they say. But there is none in heaven, either.” I think that is true wisdom and… we must give the last moments of our time for beauty, or for real people we have now, in our lives, and so on. Every event has many different sides; it is, today, very simple for young people to say, “Shostakovich was a collaborator, he was a Communist party member” – but today it is not obligatory to be a member of some party.

At the end of the 1950s, especially for Shostakovich, he felt like Hamlet – To be or not to be! – that is, to live or not to live. It was like this in his mind because after Stalin’s death (1953) was a bit of fresh air, and I remember this time, I was eight or nine years old, I remember it very well, it was from one side to the other side in all walks of life. The role of music in creating a social community was incredibly important, much higher than now. At that time, the leader of the Soviet composers Tikhon Khrennikov (1913-2007), was a composer – not a high composer, but good, and his idea was not to ever help somebody who might be a better composer than him. In fairness, I must say that Khrennikov managed to save the Union of Composers, unlike other creative unions – ones for writers, artists, theatrical figures, where there were many victims of the Great Terror after the war in the 40s. But it happened with a lot of conductors as well, ones who didn’t want a guest conductor who were most likely better than they were.

Photo: T. Müller

Some would say that’s just another negative side of human nature…

… yes it is part of that, human nature. From the other side though, the position of composers was not only from the point of view of cultural but international presence, because internationally there were only two names – Prokofiev (1891-1953) and Shostakovich, and then later Khachaturian (1903-1978), who was from Armenia, which helped. But near to Shostakovich were some friends, who were also, as I understand now, secret agents of the KGB. They gave him advice, and it was around this time when Shostakovich very seriously considered suicide. And it was at this same time when the wife of Shostakovich had died (1954), and Shostakovich had come to his moment and he could not compose or do absolutely anything. He had two children that needed at that time to come to the light road, so to say – his son Maxim, and his daughter Galina – but Shostakovich was absolutely destroyed as a person. His friend, cinema producer Lev Arnshtam (1905-1979), who made the film Five days, Five nights (1961) invited the composer abroad in what was then the DDR. (Shostakovich was composing music for the film, a joint project between the Soviet Union and East Germany, about the WW2 bombing of Dresden – ed.) When Shostakovich got to Dresden he was given the possibility to live in Gohrisch (roughly 47 kilometres southwest of Dresden – ed.). Nothing had been destroyed there during the war, unlike the city of Dresden, which had been totally destroyed. Gohrisch was not a village, not town, but something between; it was filled with fantastic air, good views looking to the river, mountains – but Shostakovich cried every single day he was there. He could not compose, until one day he made the conscious choice to stop composing the film music and instead compose the Eighth String Quartet, one of the most important compositions of the 20th century. He wrote it in three days.

Then he received the advice to be member of the communist party, and decide all his problems in one day. He was not really a member of the party as a big ideologue – absolutely not – but most people near him understood why he made this step, and from it, he was able to compose what he wanted. He said, “The more decent people in this party, the more likely it will be better.” Oh, the naivete…!

So is knowing when to compromise the secret to inner authenticity, or merely outer peace?

It’s the secret of surviving the regime. Shostakovich’s choice was an opportunity to save himself. In Stalin’s time, he was in danger, and after Stalin died, he could’ve been a hero of fairy tales, but, I must say, political power was afraid of him, because he could write some tune for the anniversary of the Republic, or the Seventh Symphony inspired by the Psalms, or use poems of Yevtushenko in the Thirteenth Symphony with double sense – Shostakovich knew very well how to do this, not only in his big symphonic works but in his smaller quartets.

So to give some reply here… when we speak about cliché, well, it originates from a strong order: “Who is not with us is against us” and “you must know that the crocodile who ate your enemy is not your friend yet.” A cliché can today bring mass ideology, mass meaning, mass press, the point of view of one composer against another; this is all very sad, because we have really very different points and conditions of life, and if we don’t understand this, we can’t give our true selves, guilty or not guilty.

It feels like there are a lot of artists now who still have to make those compromises.

I don’t know…maybe. I understand today it is practically almost all the same thing as before. What happened with humans and those artists… there are some groups of covert artists who are, so to say, “in front”, and these artists must be, possibly, in good shape with their souls. But… I don’t know if it’s good or not-good; we are not angels. And we also don’t live in paradise.