Photo: Janina Laszlo

Throughout the pandemic era the experience, or more precisely, lack of experience, in relation to human connection has been repeatedly underlined, in both large and small ways. How might that be attained through the glare of a monitor, the click of a mouse, the sound of a faraway voice resonating through tinny speakers? As life restarts and returns to some form of normal in certain areas, an unusual if somewhat predictable paradox reveals itself, for while the understanding of human connection has risen, its evolved expression has not; indeed, there are far fewer expressions of empathy than one might’ve hoped. The compassion deficit borne of the coronavirus experience is an issue yet to be worked out and in many cases acknowledged at all, particularly within the realm of culture, where new and old ways of being have collided (and occasionally enmeshed) with mixed results. People power culture, and this is a point worth remembering as the “new normal” unfolds. Such is it that the experience of chamber music, and particularly the art of song, comes into focus for some, for it is within such a realm where one might experience, however intangibly for now, the lifeblood of those people, and the sense of connection with them which is still very much missing in so many lives.

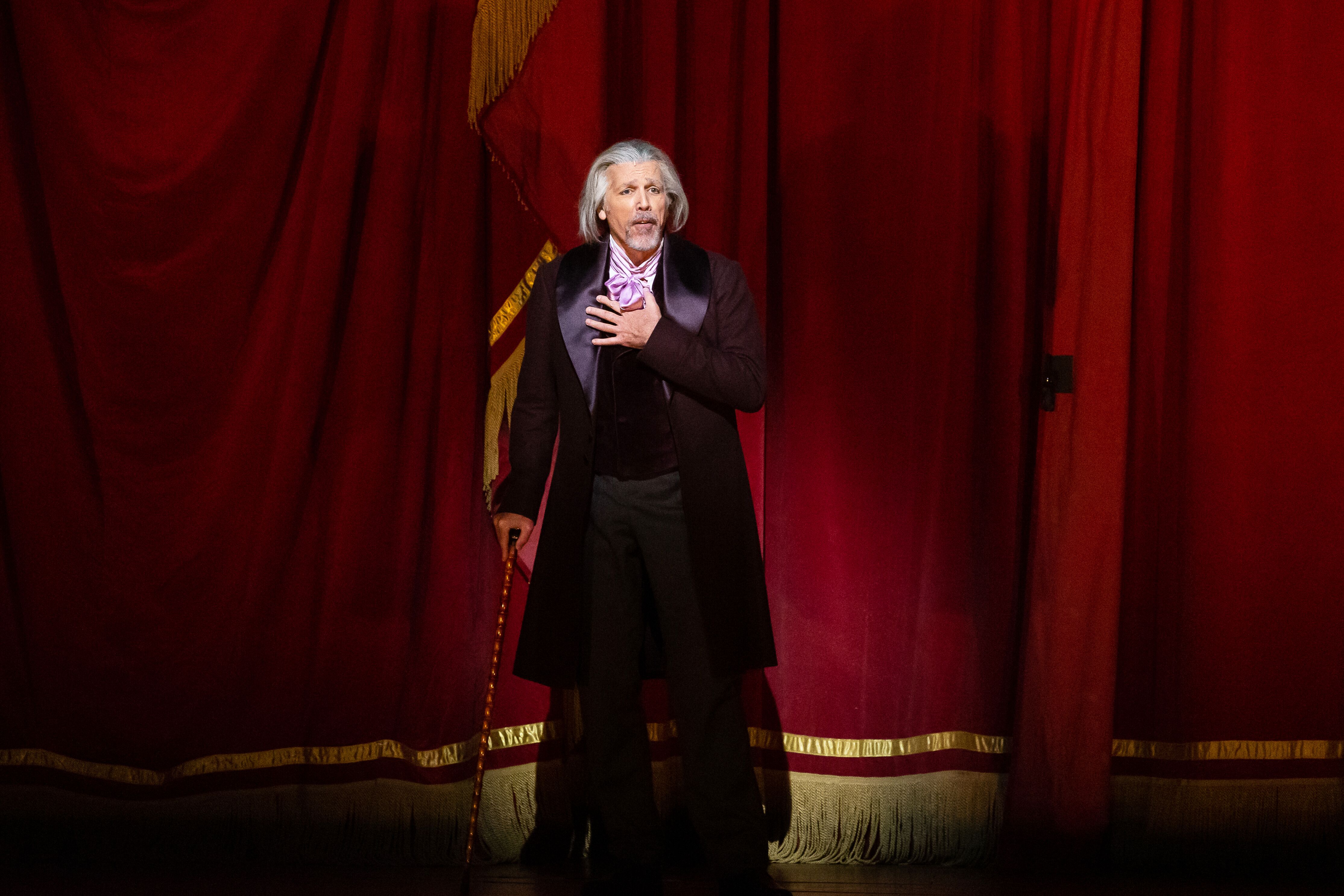

Tenor Ilker Arcayürek radiates this quality of warmth in bundles, whether on stage, in recordings, or through various online performances. His beautiful album of Schubert songs, The Path Of Life (Prospero Classical), recorded with pianist Simon Lepper, nicely conveys Arcayürek’s deft talent in handling difficult material, rendering the sometimes cold and over-intellectualized lied form with grace, intelligence, and genuine human warmth. The album, released earlier this year, is a showcase of vocal and interpretive gifts, the tenor’s rendering of “Dass sie hier gewesen” (“That She Has Been Here”) colored with the pungent longing so clearly expressed in both Friedrich Rückert’s poem and the mournful lines Schubert wove in and around them. The way he lingers on specific syllables, modulates volume between and around vowels, the careful coloration and phrasing, the watchful breath control and achingly sensitive delivery – all this, combined with Lepper’s sure-footed playing, makes for a rewarding, deeply enriching listening experience which highlights the humanity so central to the best lieder experience.

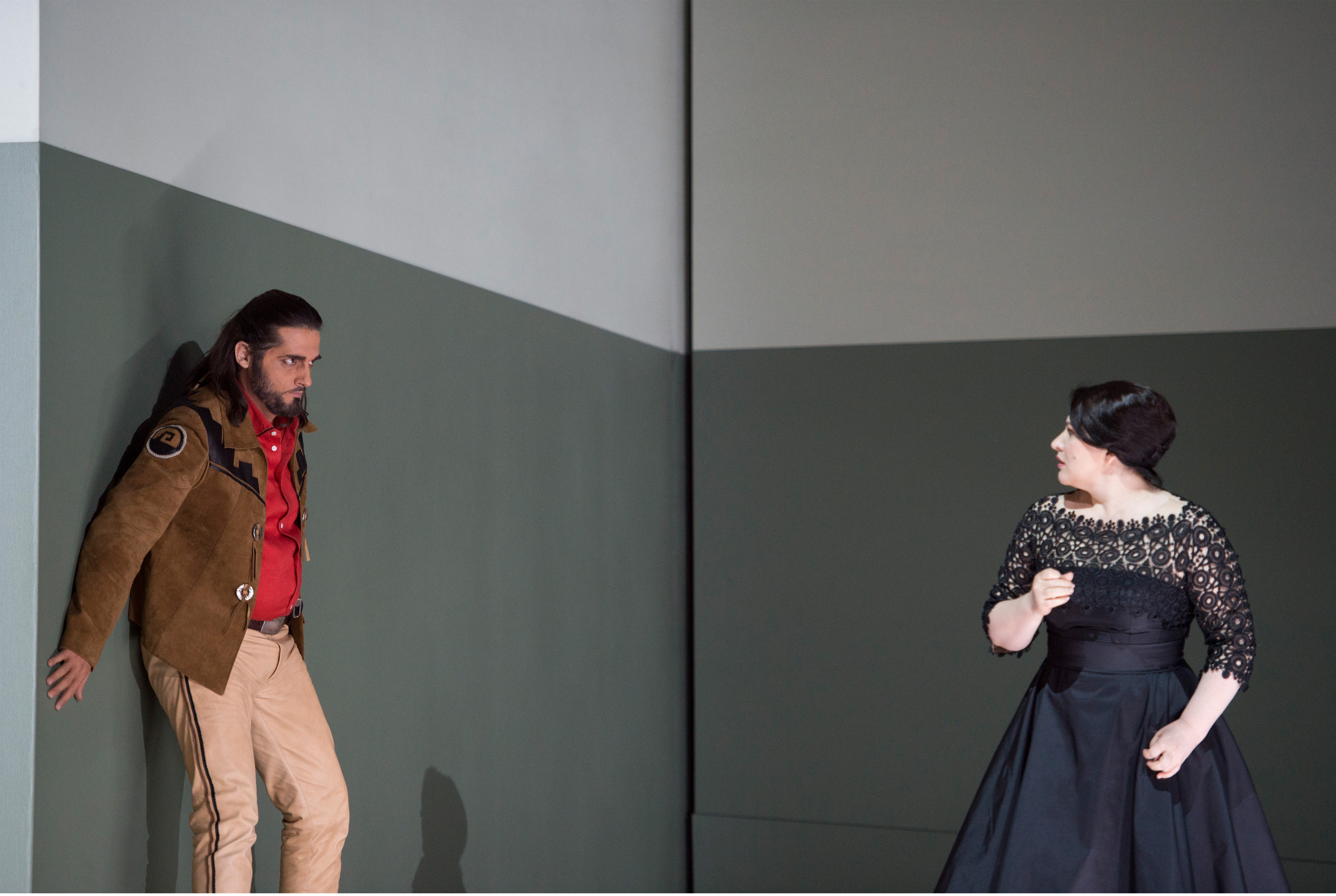

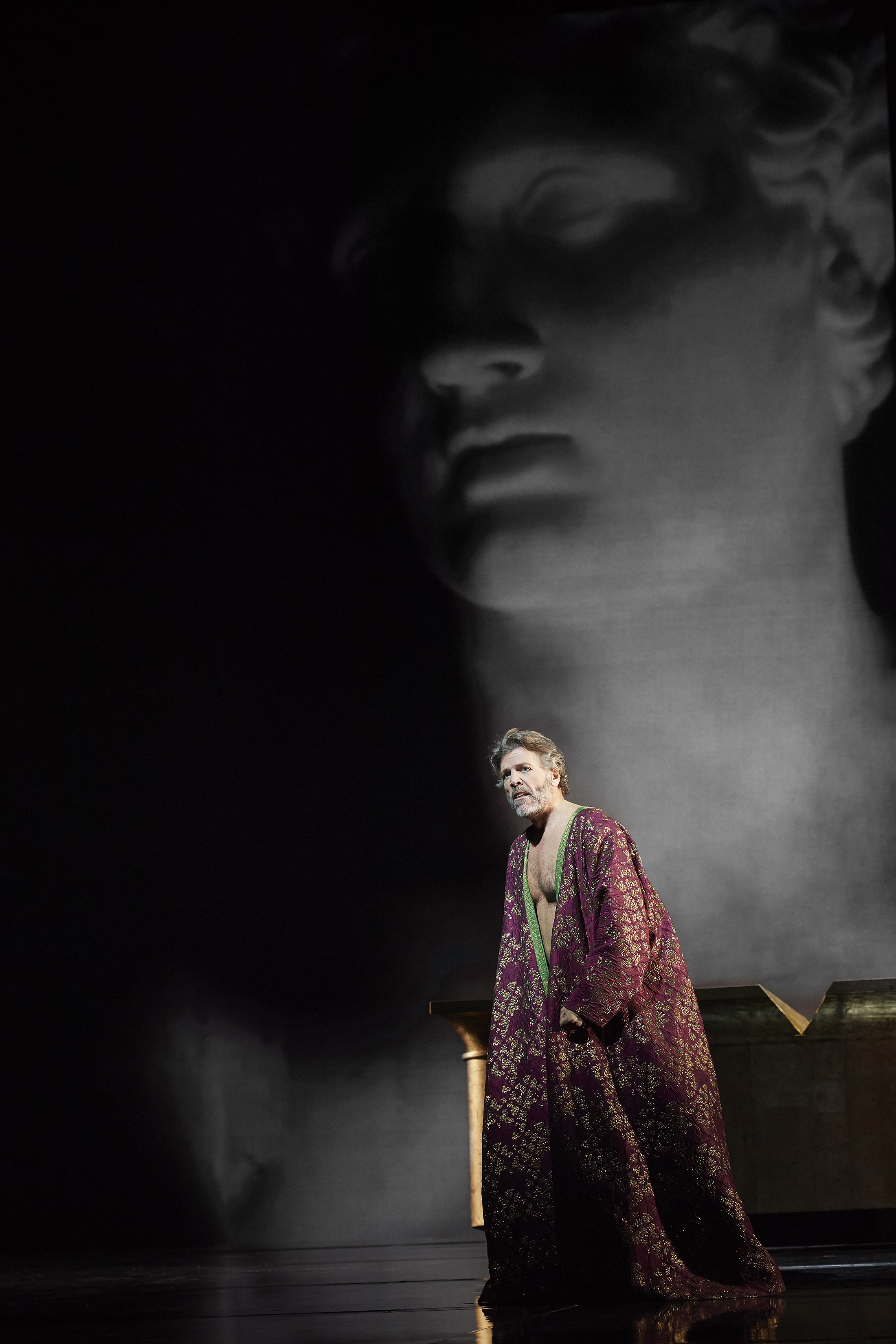

This human approach might have been influenced by a decidedly unconventional path for a classical singer. Born in Turkey but raised in Austria, singing figured prominently in Alcayürek’s youth, but conservatory training did not. In his youth Alcayürek worked a variety of odd jobs (not unlike pianist Lucas Debargue), and, as he told Turkish news site TRT World in 2018, “(o)ver time the singing got more and more, and I decided to try and live from (it)“, a decision that led to him being spotted by a casting director from Oper Zürich; he became a member of the company’s prestigious International Opera Studio, and remained, from 2009 to 2013. From there Alcayürek joined the respective ensembles at Stadttheater Klagenfurt (2013-2015) and Staatstheater Nürnberg (2015-18), performing a variety of roles, including famous Mozart-penned ones like Tamino (Die Zauberflöte) Ferrando (Così fan tutte), Don Ottavio (Don Giovanni), and the title role Idomeneo, as well as Puccini’s celebrated Rodolfo in La bohème. Since then, he has performed at Teatro Real Madrid, the Salzburg Festival, Volksoper Wien, and the Munich Opera Festival, among many others. In 2015 Alcayürek was finalist in the BBC Cardiff Singer of the World; the same year saw him as a BBC Radio 3 New Generation Artist; in 2016, he won the International Art Song Competition of Germany’s Hugo Wolf Academy. Summer 2019 saw him make his American opera debut, with Santa Fe Opera, as Nadir in Les Pêcheurs de Perles. His concert repertoire includes Bruckner (Alcayürek performed the composer’s Mass in F minor with Mariss Jansons and the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks), Liszt (Faust Symphony, with the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra and Orchestre National de Belgique), and Bach (both the St Matthew and St. John’s Passions; the former with Orchestre national de Lyon and Kenneth Montgomery, the latter with the Academy of Ancient Music and Riccardo Minasi). Arcayürek has also performed the immensely challenging vocal portion of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and more than once: with the Royal Philharmonic at the Royal Albert Hall in 2018, under the baton of David Parry, and on a Naxos recording with conductor Ádám Fischer and the Danish Chamber Orchestra, part of a complete cycle of Beethoven symphonies, released in 2019.

Balancing such grand orchestral sounds is the devotion Alcayürek has shown toward the decidedly more intimate world of lieder. The Edinburgh International Festival, the Innsbruck Festwochen, the Schubertiada Vilabertran (Spain), and the deSingel Antwerp, are just a few of the venues in which he has given recitals; in 2018 he told writer Frances Wilson that the celebrated Wigmore Hall, where he has also notably performed and recorded, is a place in which he feels “very well linked to the audience.” The distinctly larger Park Avenue Armory in NYC was the location of the tenor’s American recital debut in 2019 alongside pianist Simon Lepper, with whom he also recorded his debut disc in 2017, Der Einsame (Champs Hill Records). The title references not only the contents of Karl Lappe’s poem, but the idea of solitude as a state of being, one Arcayürek explores in various facets throughout the album’s 23 tracks. As he writes in the album notes, “(w)e can find ourselves alone as the result of many different circumstances in life – unhappiness in love, a bereavement, or simply moving to another country. For me, however, being alone has never meant being ‘lonely’. As in Schubert’s song Der Einsame, I try to enjoy the small things in life, and, especially in those times when I am alone, to consciously take time out of everyday life and reflect on my own experiences.” At the time of the album’s release, Alcayürek was praised by The Guardian’s Erica Jeal for his “airy, easily ringing tenor that puts across words beautifully, with power in reserve yet a hint of vulnerability too.”

It’s that very vulnerability, and the willingness to explore it through careful musical means and smart creative choices, which makes Alcayürek’s artistry so special, particularly now in the time of pandemic; perhaps the classical music world needs the sort of sensitivity and compassion which are so inherently a part of his approach. We started off our chat by discussing the ways in which perceptions of solitude have shifted as a result of the “new normal” and how this “new” aspect led him to perform the music of Benjamin Britten, which he performed back in March in a livestream with the Amsterdam Sinfonietta.

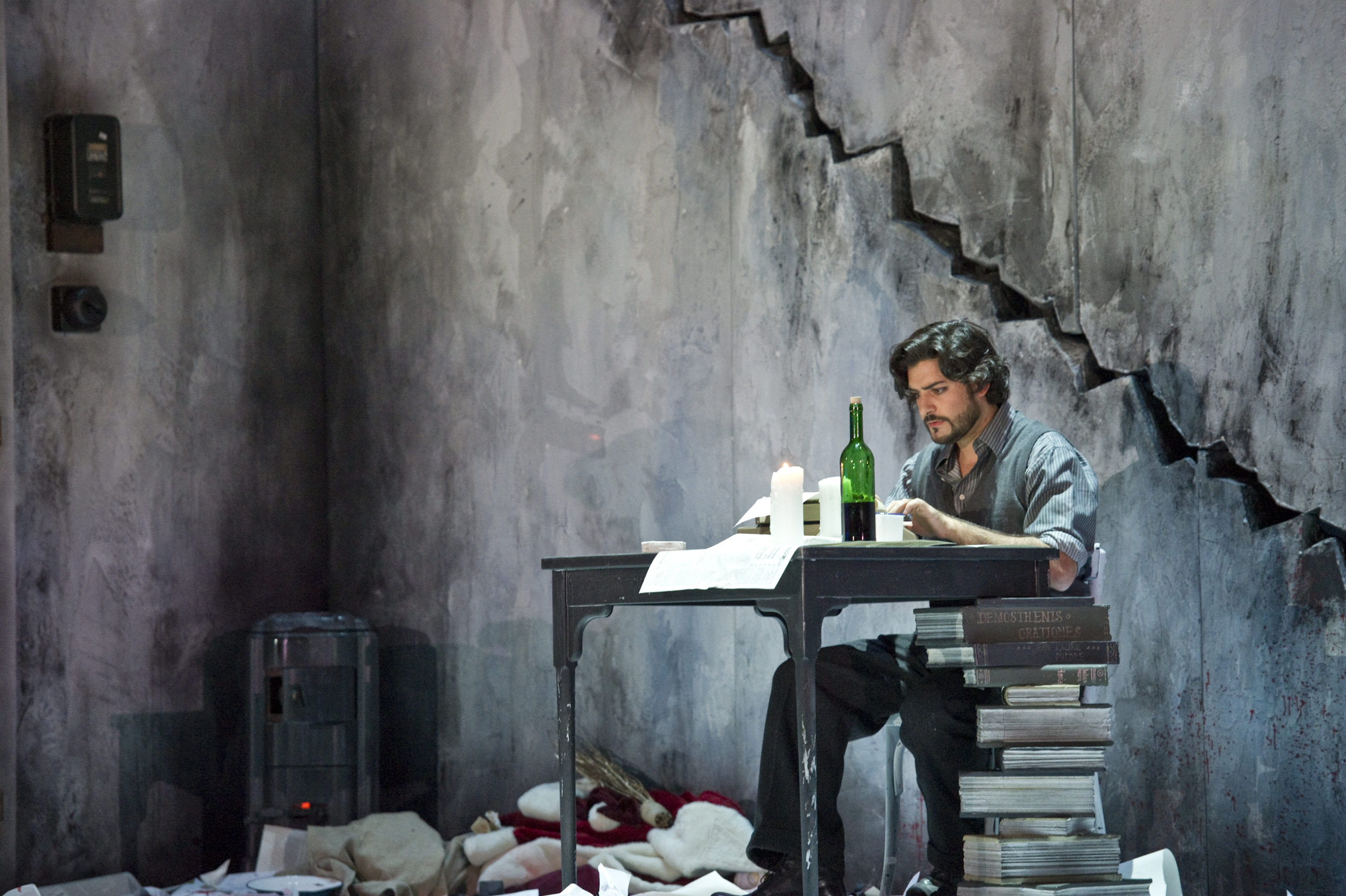

As Rodolfo in Staatstheater Nürnberg’s production of La bohème, 2015. (Photo: Jutta Missbach)

What has your experience been through this time?

It’s been an opportunity I would say; every challenge has good parts and also negative parts. But I see (this era) as a call to use my time for another approach, another way. I get the chance to spend more time with my daughter, which is great, and I have the chance to explore my barista qualities, and to work on my latte art! You also recognize the small successes of life, and realize every day has new challenges – this became my motto, actually: you realize that singing is very important – it’s nice, making music, it’s essential – but on the other hand, you realize how much you have missed in the last couple of years by spending time on different things.

Those “different things” took in new meanings in the pandemic; has this been the case for you?

Definitely. But it’s strange to talk about! It’s like talking to a psychotherapist, because on the one side I do miss being in a hotel, I miss being on my own sometimes, because I used to be lonely and it became part of my life, to be lonely and on my own a lot, and have time to think about things, and now suddenly, you are responsible for the dishes, you are responsible for the cooking, you are responsible for all these things you missed out on in not being home – and also you are very involved in raising your child. It’s things like that you think about now. And it can be difficult to balance everything.

And I’d imagine having an album out now too, and seeing things slowly reopen in some places, underlines that divide.

Yes, for sure.

How much has your approach to singing has changed? Is there any stress at moving between the various-sized venues which are so much a part of any singer’s career?

Not very much, because every performance is a live performance and I react to the reaction of the audience. That’s especially important when you come from the chamber music world. It’s easier to get in contact with the audience in that world, and to react, and to get their reactions, than what happens on the opera stage, because on the opera stage you just see a dark room usually – you don’t have the faces you can rely on. When I sing Schubert and I see somebody crying, I am touched and I know I am in real contact with that person, and so then I try to bring the audience to me, somehow. I do the same in opera, or try to, but it doesn’t matter the size (of the venue); you have to just be connected with the music and then not act – you know, like “act” – something (which could be construed as) sincere but be as honest as possible in that moment.

But is that honesty easier to access now, because of the pandemic? You along with many musicians have been forced to examine your own approach to your work, and that related sense of honesty, in relation to music-making for over a year now.

It’s like this: when you make this music, when you perform, it’s all about honesty. And for me, I try to find a relationship between each song and my life. There are some funny songs like, “I wish I were a fish” (“Ich wollt’ ich wär’ ein Fisch“) – so it’s happy, and if you read this music, and read these kinds of poems, it has nothing to do with our time, but the honesty and the message within those songs has everything to do with our time. You could make a tweet instead of writing this type of poem now. The message and the honesty within a work like this will always survive, so this is what I try to do, to convey the honesty of this music to our reality now, because we all know the pain of love, and the nice moments too, and also the moments of reflection, or the moments of acceptance, and this human desire, these deep wishes – I try to bring out all of that during music-making. Yes, these are also the topics which people from the 18th and 19th centuries were working with, and they are still up-to-date.

How much do you think there is more of a place now for lieder, and chamber music – these smaller more intimate musical experiences? In my chat with Helmut Deutsch earlier this year, he seemed to think the pandemic had opened a new door for the art form.

I think lieder, and the way people think of it, is changing a bit.

How so?

You have to see it from an historical perspective. Lied was quite popular after the Second World War, but it was performed with a different approach, and in a different way than it is now. Lied was like, how can I say this, like a theatre piece, performed as a piece of art but maybe not with the same view, like I personally bring now, because emotions were kind of forbidden in that period, so it was more to bring people joy after this time of suffering.

As artsy escapism?

Yes, it was more like singing nice melodies, like a form of escapism, as you say, and I think now it is about time to break that, and say, “I am a musician, reading my own poem, and bringing this to you, and trying to explain my own personal story.” I think this is the next level we have to achieve. Also it’s vital to make lieder, the art of lied, interesting for a broader audience – the big difference between lied in the 1950s and nowadays is that people were educated about it in school, and they knew the poems which make up the text of these works. But nowadays people don’t know the poems. So getting to know these written works and their authors is another way to explain it, and to bring the audience into this music, and into the poetry, into this artwork overall, like the understand which existed before.

Maybe one small story: the first time I sang in New York was at the Park Avenue Armoury, and there was a young couple sitting in the first row and they were quite fashionably attired, the guy in the couple looked like a rock star; we met afterwards in a bar by chance, this place where we all went for a drink, and he said that he’s also a musician, and although he didn’t understand a word I sang and didn’t know the music either, he felt the emotions inside. So he understood on this other level. That was a very interesting experience for me, to hear that – I really liked it! And I think this is exactly what it’s about, to transport emotions, and not play them falsely but to live them. Singing this music needs a lot of life experience. For certain pieces I sing I think of various aspects in my own life, and these things make me emotional, and I try to express myself in a way that touches on those things.

Good lieder should connect to real life experience – and some of us can’t applaud at the end because we’re processing everything…

I prefer when people don’t applaud immediately after my singing.

Do you?

Yes! For me, pauses, within the music but also after the music, are really important, so I really try to also have a moment of silence. I really enjoy that, especially after signing a cycle like Winterreise; I think it’s important to digest the music for a while, and then applaud, or not.

How does that translate to a venue like Santa Fe? What was that experience like?

Scary! I loved it a lot, but it’s scary, because the winds can be a challenge. It’s open-air, so you are affected by the weather, and it can be very cold, very hot, very windy, and suddenly there’s lightning; you see the clouds moving around and you think, “Oh no my aria is coming! If the winds come in on this side, will people hear me if I stand there?”” But oh, it was a very nice, very special experience, and I’m so glad I did it.

And it’s quite large, isn’t it?

It’s huge, I think it’s more than a 2000-seat capacity.

The other houses you’ve sung at are such a contrast – Zürich is very jewel box, for instance.

… especially in Zürich, yes. And it has a really good acoustic, and the seating, the way that’s built, was done with an angle, so the acoustic lifts up, which makes it easy to sing in. It also gives the singer the opportunity to step back and not sing at 100%, so you can create more colors, you can be very musical. Because of that (design), you are not using your full capacity, so you always have 20% left. My teacher said that in such a spot you are singing with your, how do you say it in English, it’s like with a bank account, you don’t sing with your capital, you sing with your…

Interest?

Yes, the word I was looking for, interest! (Jewel box-sized spaces) give you the freedom of playing around and not going to the very, very edge, and then if you do go to that edge once or twice, it’s to build up a climax.

Interior, Opernhaus Zürich. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Indeed, one is able to hear so many colors in that house. You were part of the opera studio program in Zürich, yes?

I was in the opera studio at Zürich – most of the time I sang smaller parts during my years there. I used Zürich as my study spot actually, and I got some stage experience from singing in choir before, so (working at) Zürich was useful to get some confidence and security onstage, to find one’s self.

It seemed like a good place for that, and not only because of the singer-friendly acoustic.

I must say, it’s still one of the best houses. During the time of Alexander Pereira, the former opera director (Intendant of Oper Zürich, 1991-2012), it was filled with all the stars of the business – Netrebko, Nucci, Hampson, Bartoli, Camarena, and Kaufmann as well, to name a few – so it was just great for me to observe those artists, to be around them, to work onstage with them; you get so much input by seeing these people and getting the chance to be close to them. You also get to know in which places they save their voice, where there is the possibility to do that, when they go on their edge and how – things like that. I was amazed at being part of the whole thing. Later when I came to Klagenfurt, the first time maybe, of course, it was clear the orchestra was different, and there were challenges, but you find new ways to deal with those challenges, and ways to grow through them. Nürnberg was my first state opera experience, so it was a bigger orchestra again, and my debut there was La bohème of course – and I can tell you, the first time, with a German orchestra playing Puccini, is also not so easy! And in comparison to Zürich the acoustic in Nürnberg is, again, not the same either. So you have to adapt to each room, to each space, each orchestra, and you have to find your strategy in how to manage the whole situation, and your role within that situation.

That’s a good education is it not?

It is definitely good! As a singer you will always learn new things and adapt to situations, so after the pandemic I’m really curious what will happen with artists; I’m sure some singers will struggle, at least for a while, until they get back to shape. You can sing as much as you want at home, but it isn’t the same as singing on a stage, and you won’t have the same feeling of adrenaline and excitement. It’s another level of singing, like for a basketball player, the difference between the training and then the game. When you have people in front of you, it’s difficult to make that throw the same way.

Some singers have expressed those kinds of concerns; how much have your pandemic activities helped set the stage, to whatever extent, to going back to the actual stage?

I haven’t been singing recently so much. My last project was in March, so not so long ago, but it was during that experience that I sang, for the first time, the Serenade (Serenade for tenor, horn, and strings) by Benjamin Britten with the Amsterdam Sinfonietta, and it was in a hall which is not so big. It was like a normal concert venue size – and it was different to sing not for an audience who’d normally be there, but for the microphone, because it was a broadcast concert, so.

That’s a whole new skill, one many are learning: how to sing for the internet.

Exactly! I mean, I have had some background in recording and singing for radio or for CD, but this project was still a new experience for me because I was singing for an audience without having an audience, so it was a mix between live performance, where you sing for the audience, and a CD recording, where you don’t. It was something in-between.

So was that Britten piece back in March a sign of things to come?

I wish I would sing more of it, actually, because the music is, for me, it was… musical love at second sight. Can I say that?!

Yes, that’s precisely my experience of Britten’s music too.

Really, it just happens sometimes with some composers!

Well I wasn’t raised to his work…

… me either! I was raised more to the music of Schubert and Mozart and so on, because I sang at the age of 9 in a boys’ choir, and we never got in touch with the music of Britten, we weren’t raised with it, like in the UK for example, when you sing Britten in choir, so it’s a totally new world for me and a new language, not the English language, but the musical language – the harmonies, for instance – but I really, really enjoyed singing this piece, I must say! I was surprised at how much I liked it.

https://vimeo.com/528266890

It suits the timbral quality of your voice, and you bring a warmth to music which is not always perceived as warm (rightly or wrongly!) – but your approach is very sensitive.

Whatever you sing, you have to sing it with your voice. And yet there is always the sound of Peter Pears in one’s ear, or head, when singing this music. People know these pieces through Pears’ recordings. Friends in the UK said, “It’s hard to imagine you singing this because we have it in our ear with Peter Pears”, so I really tried not to adapt or imitate at all, but to sing it my way. Also, these pieces are a fit for me, I think, because they’re like singing lied but with some moments more operatic – it can be difficult to find the right balance, to find colors, which you need, which are connections with that world of lied, but also with the technique which requires operatic singing. It’s interesting, his music is right on the edge for me, and singing his work is a balancing game.

I want to hear you sing more Britten.

I hope I do more of it! We shall see what the future holds.