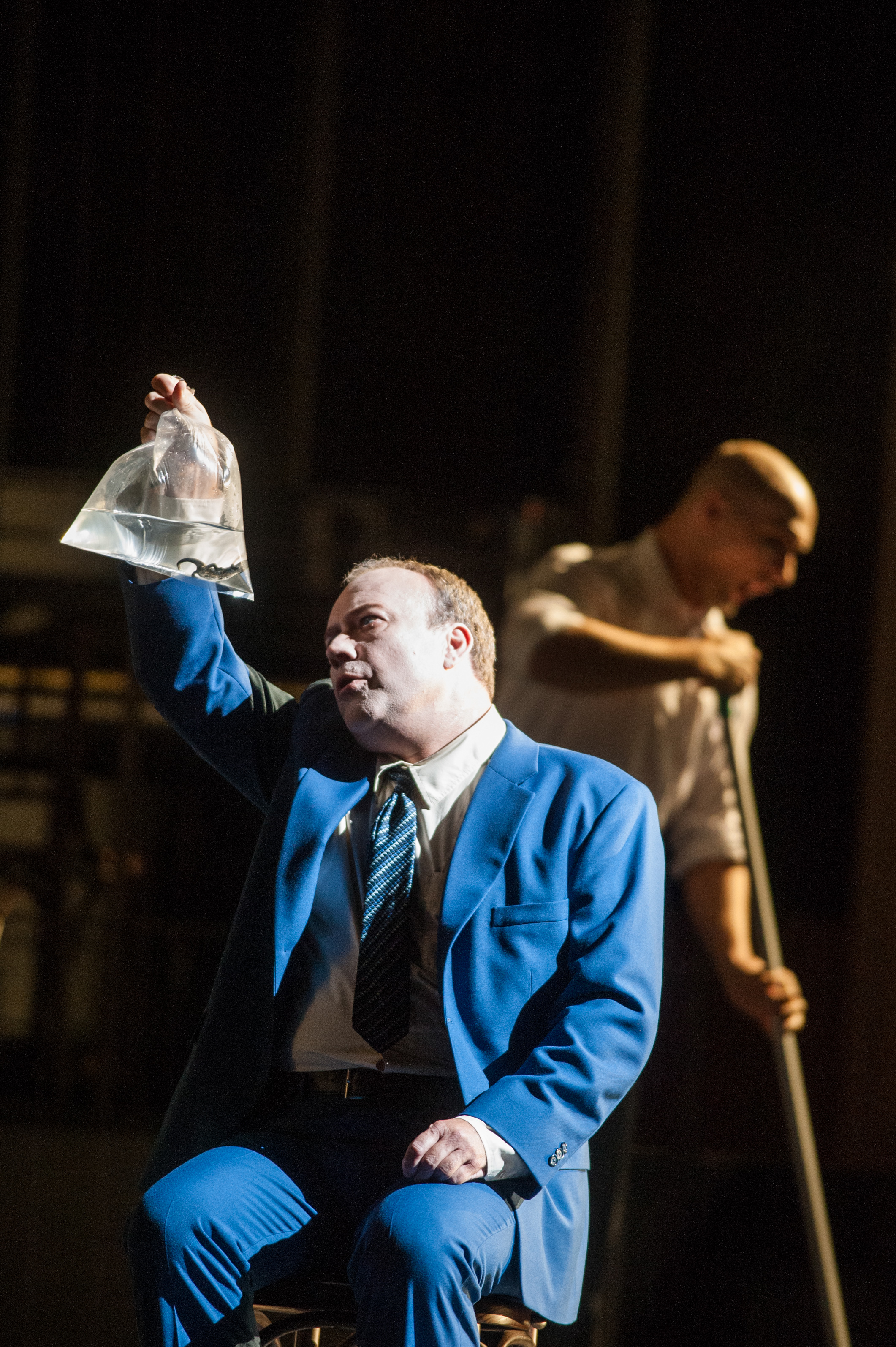

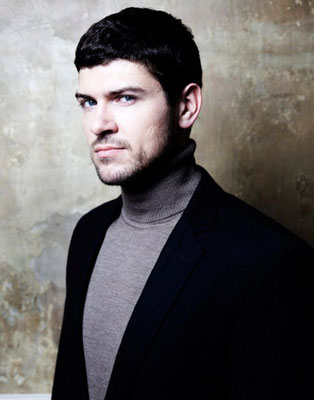

Photo: Tom Schweigert

Baritone Dominik Köninger has been busy since our last conversation. That isn’t surprising, considering he’s a member of the Komische Oper Berlin (KOB) ensemble, where he’s sung a variety of roles, from a myriad of eras —Baroque, classical, bel canto, operetta, modern — since starting there in 2012.

Any artist who’s experienced the ensemble system is aware of the need to balance wildly different material in very short amounts of time. Scheduling and repertoire means a careful adherence to vocal sensitivities and recuperative demands, to say nothing of the challenges that can be presented in working with a sometimes revolving set of artistic personnel. During my chat with Wilhelm Schwinghammer this past January, the German bass baritone spoke of his own time as a member of the Staatsoper Hamburg ensemble, estimating he performed over seventy roles during his decade-plus time there. Ensemble work can also be an incredibly important and useful experience in developing skills, getting to know repertoire (well) and cultivating specific and sometimes entirely unknown talents. One might enter into one with the belief of being suited to doing x type of repertoire, only to learn (through time, experience, and exposure) that in fact, y type of repertoire is probably a better match vocally (and that z repertoire, which had never before been even vaguely considered, is suddenly looking interesting too). Ensembles have their ups and downs, but for some, they give needed grounding, requisite exposure (to audiences, repertoire, directors, conductors, and potential future houses), oh-so-vital flexibility (vocally and otherwise), and a broadening of perspective — all of which are so important to a burgeoning career.

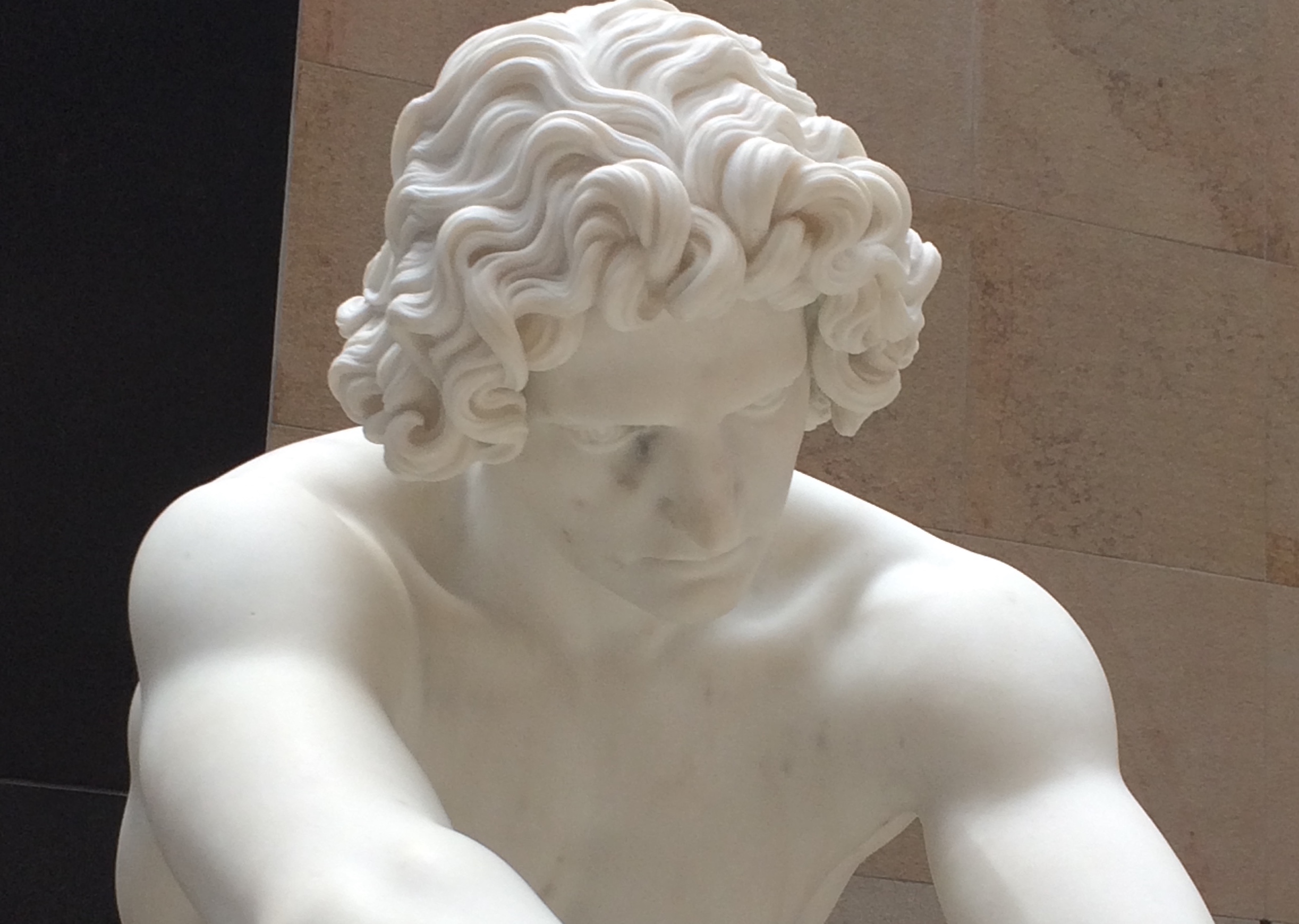

As Pelléas in the Komische Oper Berlin production of ‘Pelléas et Melisande’ in October 2017. (Photo: Monika Rittershaus)

And so Köninger has done much since we last spoke close to two years ago. As well as making a much-awaited role debut as Pelléas in a brilliant and bold, brilliant production of Pelléas et Melisande directed by KOB Intendant Barrie Kosky, he reprised his role as Silvius in the frothy Oscar Straus operetta Die Perlen der Cleopatra (The Pearls of Cleopatra), appeared as Agamemnon in a colorful production of Offenbach’s Die schöne Helena (The Beautiful Helena), sang Papageno (something of a signature role) in the much-vaunted KOB/1927 production of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), and gave a recital (one I found very moving) full of dark works by Mahler, Grieg, Mendelssohn, and Schubert. Along with more Silvius and Papageno performances this season, he’s also singing (/has sung) Maximilian in Bernstein’s Candide (with KOB), and Pantalone in Prokofiev’s Die Liebe zu drei Orangen (The Love for Three Oranges). A well-received recital of Schubert’s celebrated Winterreise closed out 2018. This spring Köninger will be on a mini-tour with RIAS Kammerchor and Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, in a presentation of Bach’s St. John Passion. For those of you assuming you may have to travel to Europe to hear him live, fear not: Köninger is set to make his North American debut next spring with Opera de Montreal, as Papageno, in Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), which he lovingly refers to as “my baby,” a nod to his history with the presentation.

This coming Saturday sees another first for the baritone: he’ll be making his debut in the title role of Handel’s rarely-staged opera Poro, Re dell’Indie (Porus, King of India), called simply Poro here (Poros auf Deutsch), which made my Things To See 2019 list. The story revolves around Alexander the Great’s time in India, and the love triangle which arises between him, King Porus, and Cleofide (aka Cleophis), Queen of a neighbouring realm. Handel’s opera is based Alessandro nell’Indie by celebrated Italian poet and librettist Metastasio, a work that inspired more than sixty other operas throughout the 18th century. The Komische Oper Berlin production opening this coming Saturday (March 16th) is led by conductor and early music specialist Jörg Halubek, but is may not strictly Baroque in that frilly-cuffed, big-wigged way; its celebrated director, Harry Kupfer (who was trained by KOB founder Walter Felsenstein), has, as you will read, made a few updates. The leap from Pelléas to Poros for Köninger isn’t as wide as you may think; his intense focus comes from a place of commitment and utter humility. So no matter the variety of plant, the ground beneath it is rich and sure, and is being continually cultivated with the utmost care and consideration; you can hear it in his voice with every performance, at the Komische and not. Köninger, quite simply, is one to watch.

The role of Poro was originally written for the famed castrato Senesino and is usually cast with a counter-tenor; in this production, it’s a baritone (you!) — what’s that like?

The whole thing is a bit of an adaption. It is Kupfer’s wish to have baritone in the lead role. In the 1950s, he was an assistant director in Halle, which was then East Germany, and they did this opera, but in German, with a baritone in the lead role — that was his intention. So putting it on now, it’s kind of the circle closes. He wanted the opera to be in German now as well, so we got a German translation — it’s more like an adaptation than a translation. Our production is set in British colonial India, a very specific and political time and context.

So Mayamaha in this production was originally Cleofide?

Yes! These are Indian names in the production: Gandaharta (Philipp Meierhöfer), Mahamaya (Ruzan Mantashyan), Poro’s sister Nimbavati (Idunnu Münch). That’s what Kupfer intended. Also, the role of Alexander, which was originally a tenor, is now a counter-tenor (Eric Jurenas). It’s all been adapted, but it all makes sense.

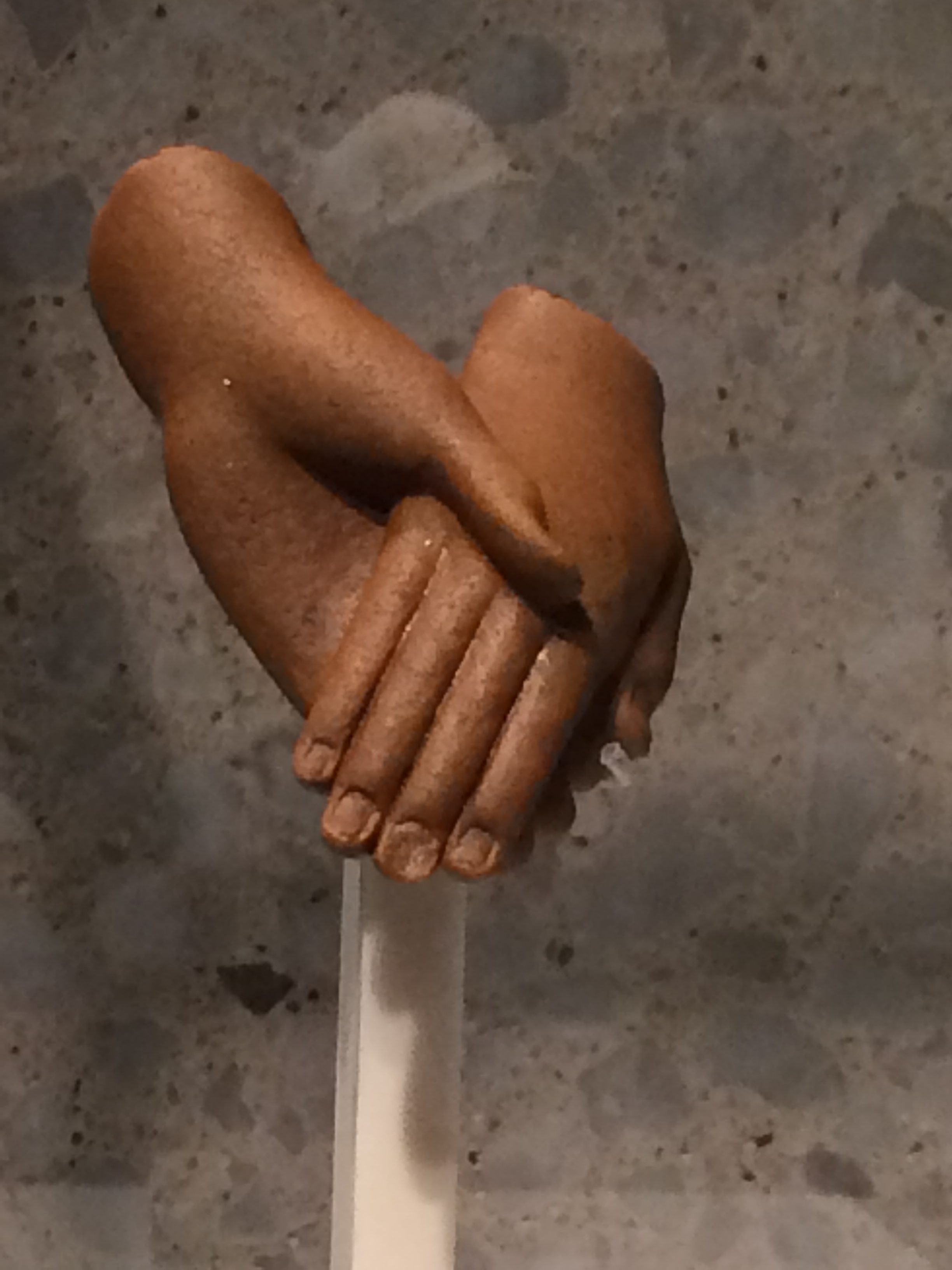

As Poro in Komische Oper Berlin’s ‘Poro’ (Photo: Monika Rittershaus), opening on March 16th, 2019.

What’s it like to sing? Poro seems quite different to Handel’s other operas musically.

This opera is not so full of the fast coloratura arias and the demands of being perfect stylistically, but the challenge this time is that it brings much more out emotionally. Handel wrote these arias in a different way; he didn’t write them with fireworks, although there are some like that (like with the counter-tenor). Kupfer is keen on having us not doing too much when musical things change, but to have it more clear, more simple. It’s like, he doesn’t like a singer to show off. He wants real feelings, and to hear not what they can do with their voice, but to bring out the emotional colors of the voice, with the text and body, and the heart.

Is this your first time working with Harry Kupfer?

No, actually not, we did a production of The Merry Widow in Hamburg years ago. I was just starting out then, and it’s different now. I’m much more experienced. The match is really nice. We had a good long rehearsal period and Kupfer was really detailed and really precise with what he wanted. First he broke down — and that’s what I like about his detailed approach — he broke down every recitative to its core, at the very beginning of rehearsals. If you would’ve heard this, you would’ve thought, “How will this all work?!” All the recits were so long and there were so many pauses, and it went so slow, because he wanted us to have the thoughts first and then sing the lines, or use the pauses while showing that we are thinking about something else and we go in a different direction, so it would make sense. That’s what I really liked about this project; this is a totally different style of theatre, and very different if you compare it to Candide or Cleopatra, but this is the fun part for me, doing various things.

Photo: Jan Windszus Photography

Like St. John Passion…

Yes, of course. It’s a small tour: one day in Italy, then Munich, then the third day we’re in Berlin. I’m only singing Jesus, so for me it’s just a few recits, but it’s a good way to connect back with the RIAS Kammerchor and with the Akademie für Alte Musik. My schedule is a mixture of heaven and hell, black and white, yin and yang.

Is that good for you as a singer?

Yes, it keeps me really flexible, and I like that. Working on the Handel, I think I have six or seven arias in total but two are quite fast, so it’s really nice. Keeps me flexible — in the head, in the voice.

What repertoire would you still like to do?

If you talk about the next five years, it’s just the usual suspects like Giovanni or Marcello, but if we talk ten or fifteen years, there’s Onegin to discover, maybe there’s a little bit of Wagner, but I’m not sure about it because I have to see how the voice develops. The French stuff has of course a lot to discover — like Hamlet from Thomas, which would be great, but houses rarely do this sort of repertoire.

And there’s the Lieder works as well.

Of course yes, there are plans for making a CD, but you need time and preparation so I’m not sure when that will happen, but we’ll see. It is a difficult business; you’re always touring around, you have so many appointments and there isn’t always time to give everything to this one concert. There is a lot of responsibility every time you do a recital. People come to hear you and you need to be prepared, and learn the music by heart — that’s the very basic work, yes? Then you have to dive deeper into this new world, and it’s a responsibility, every time. And sometimes it’s hard to fulfill. It’s why I’m careful; I still have my opera engagements and my contract here in Berlin. Having recitals scheduled between, for instance, a Candide here and a Poros there and few days later a Pelléas… you know, it has to be well-chosen. Mentally, strength-wise, everything; it’s hard. I’ve been constantly working now since September — I just went from one thing to another. But I’ve really enjoyed focusing only on the Handel for the last six weeks. Once this is done I’ll prepare for my next recitals. When it gets calmer, it gets easier to let everything sink in.

What’s been the most surprising thing so far?

This Handel opera is much easier than the past ones I’ve done! I did Giulio Cesare in Egitto a few years ago; it had much more in terms of coloratura and furioso arias. I was younger. You grow with every challenge and every single thing you have to deal with. Maybe if I hadn’t had that experience four years ago, Poros would be that sort of thing now, and I would be a little bit struggling and lost and more fighting — but this time, it’s good, I’m super-relaxed, even though we open soon. When I’m relaxed I’m more on top of my game than when I’m closing in on myself and wanting something. If you really want something specific, it’s the wrong approach. That’s the surprising thing I discovered doing this. And of course the relaxed and productive way of working with Kupfer and Halubek, and Ruzan and Eric — it’s been a really nice, really positive experience.