Every day comes the email reminder: It’s time for your German lesson! Daily practice is key to learning a new language! During the worst of the pandemic lockdown I took formal lessons with a real, live teacher via Zoom; the experience was a useful and stimulating way to integrate education and interaction. Those months were indeed fruitful but pricey, and proved ultimately too dear for my limited budget, and so I am now left with basic, self-directed gadgets and services, and to my own analogue study, pursuits which demand other forms of payment (namely energy and attention) that I am not always able to give. It pangs me to consider the extent to which my language skills have slipped away, what with memories falling like raindrops lately – of winning fancy language prizes during elementary school days; of the praise garnered by my mother for pronunciation and swiftness of comprehension; of casually shrugging it away the way teenagers so often do when other interests enter and academic responsibilities loom. Playing linguistic catch-up (otherwise known as jumping in the deep end) as a middle-aged freelancer is daunting, exhausting, often disheartening, but passion for culture renders it necessary, and if I am being honest, uniquely rewarding.

And while knowledge of languages isn’t obligatory to opera appreciation, especially with the introduction of surtitles in 1983, such knowledge deepens the experience considerably. I always felt I was being left out of something, anything, everything, in not knowing opera’s prime languages (Italian-French-German) as well as I ought. That knowledge is slowly expanding, but so too, is my appreciation of the art of translation itself. Companies dedicated to presenting works in their geographically-specific local language (like the English National Opera, and once, if less so now, Komische Oper Berlin) would (do) rely on translations that aim to capture the nuances of both text and its relationship to and with orchestration and scoring, and (in some cases) to the contexts in which the work was first created and presented (and/or contemporaneously produced). Many composers have actively participated in translations of their works and/or collaborated with their respective text-based counterparts; among opera’s most famous librettists/translators are Alfred Kalisch (1863-1933), Edward J. Dent (1876-1957), Andrew Porter (1928-2015), Amanda Holden (1948-2021; her work will be the subject of a future feature here), and the famous team of W.H. Auden (1907-1973) and Chester Kallman (1921-1975). Auden-Kallman wrote, along with collaborative translation on works by Mozart, Weill, and Dittersdorf, original libretti for living composers, including Stravinsky (The Rake’s Progress, 1951) and Henze (Elegy for Young Lovers, 1961; The Bassarids, 1966). More recently, to take just one of many examples, English National Opera’s production of Die Walkure – or The Valkyrie – in autumn 2021 was presented in a singing translation by musician/scholar John Deathridge, whose own meant-for-reading translation of Wagner’s epic Ring Cycle was published by Penguin Classics in 2019. The book points up a vital aspect of the industry that has faced new challenges in the digital era, most particularly with the rise of streaming services amidst pandemic.

Any opera lover will know, probably too well, that hitting “translate” on a video lacking formal subtitling invites a world of frustration; the result is mostly comical, and stems from a longstanding caption problem on Youtube. Even with the insertion of formal subtitled translations,the nuances of expression are often lost, drowned out in weird mishmash mixes of intended accuracy and grammatical gibberish. One can’t help but notice the many inadequacies in watching various introductions, talks, interviews, and previews released by opera houses, orchestras, and other classical-related organizations, when it comes to translation options; the varied socio-cultural / political / historical contexts are often binned in the name of (one supposes) expediency, digestibility, an ever-present pressure to get a post up quickly with the least amount of fuss and satisfying ever-shrinking arts budgets while hoping to garner the ever-desired sexy clicks. Is the arts world really so ready to throw something as important as translation to the side? Isn’t it a foundational part of attracting new audiences (and keeping old ones) to cultivate meaningful comprehension (and thus engagement)? At such moments the digital world seems woefully ill-equipped for the demands of translation, yet the internet would seem to be the very spot to offer more fulsome possibilities for the sort of nuanced appreciation that best serves the repertoire – thus arguably increasing its overall appeal. Someone, surely, must be able to build something(s) better, a system organizations at any level can access that goes beyond Google translate (or deepl.com) limitations – but then, someone, something, surely, must fund all of it, and aye, there’s the rub. But how much meaning is being lost in the meantime? How many potential audiences? How many potential ears, minds, hearts?

Of course there is no substitute for direct sensory experience when it comes to the marriage of music and words, but the key, as ever, is finding the time. One of my favourite if too-rarely enjoyed activities is spending a day (a week, a month) studying an opera libretto and related score, large pot of fresh tea at hand. Noting the rhythm of language, the shifting colours of sounds, the ways in which the dynamism of vowels and consonants shapes and informs musical lines and orchestration; pondering interactions, phrasings, silences; these are gifts to be enjoyed and explored, over and over. The act of reading a libretto (especially aloud) gives one a simultaneously broader and more intimate relationship with words, with sounds, with flow, intonations, and emphases, the way they all feel in the mouth, carry-float-sink-shoot in or through the air – such a reading allows a greater comprehension of the world of words, of the work’s creators, and all those who’ve presented it since. Thus does the world become larger and more detailed, all at once. Deathridge did the world a great service indeed with his Ring book, but his efforts rile my writer’s heart for giving a sharp reminder of the fact that so few other opera-text ventures exist in the 21st century. There is clearly a long history of writer-composer relations – Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Stefan Zweig worked with Richard Strauss, for example, and the texts of Friedrich Rückert and Clemens Brentano (among many others) were used by Gustav Mahler. English translations of these writers and others do indeed exist, though the output when it comes to their musical manifestations is spotty; those which are extant in scores, such as those which appear in the Dover editions of Mahler lieder, are far less than ideal (and don’t list translator names for the most part, pity). Indeed they may be intended for phonetic starting points, and as the bases of introductory study for musicians, but they are decidedly not a comprehensive whole. The ever-expanding Lieder.net is a good resource for song translations (and recognizes the translators, natch) even if it makes one long for a more comprehensive whole within the classical industry. Good English translations exist, but to reiterate, are spotty, not always easy to find, and are sometimes couched within more comprehensive volumes.

The Whole Difference: Selected Writings of Hugo von Hofmannsthal (Princeton University Press, 2008), edited by poet/librettist J.D. McClatchy, contains a highly readable, immensely poetic translation of the first act of Die Rosenkavalier by dramatist Christopher Holme, done in 1963. Years before, in 1912, Strauss’s popular opera was its first full English translation by English critic and librettist Alfred Kalisch, who championed the composer’s work and translated other operas into English as well, Salome and Elektra among them. Kalisch himself noted in “The Tribulations of a Translator”, a 1915 presentation for the Royal Musical Association (published by Taylor & Francis; Source: Proceedings of the Musical Association, 1914-1915, 41st Sess. 1914-1915), pp. 145-161) the varied difficulties of translating opera, pinpointing the issue of whether it is the translator’s duty “to produce a readable translation or singable words.” This gets to the heart of the matter for current purposes, for while the latter is a topic for another day, the former – having something readable – is worth investigating, particularly in light of evolving technologies, audience engagement, cultural discussion, and to further perceptions around various forms of identity. Smart translations matter, and readable, easily accessible ones are a net good, in the world of literature as much as in the world of music and specifically classical culture. Most creators would, one assumes, like for their works to be understood in their full range of expression, for audiences of all locales and backgrounds to be given access to those intrinsic cultural nuances which are not always part of the concomitant scoring alone.

Thus it can be said that the act of translation demands respect for place, process, history, and humanism, qualities classical (as much the art form as its artists and ambassadors) aims to embrace and promulgate. In November 1959 writer Kenneth Rexroth (1905-1982) presented a lecture at the University of Texas in which he outlined, with fascinating precision, the ways in which the act of translation (as applied here to poetry) changes according to various contexts and received understandings. Using Sappho’s “Orchard” as his first example, Rexroth offers up eight different translations (including his own) to illustrate the vagaries and subtle ways in which language, and the societies from which understandings and experiences of the world springs, informs translation choices. He goes on to observe that translation “can provide us with poetic exercise on the highest level.” Translation can do much more, as he notes:

It is an exercise of sympathy on the highest level. The writer who can project himself into the exultation of another learns more than the craft of words. He learns the stuff of poetry. It is not just his prosody he keeps alert, it is his heart. The imagination must evoke, not just a vanished detail of experience, but the fullness of another human life outside of one’s own. Making that leap requires imagination, but also compassion.

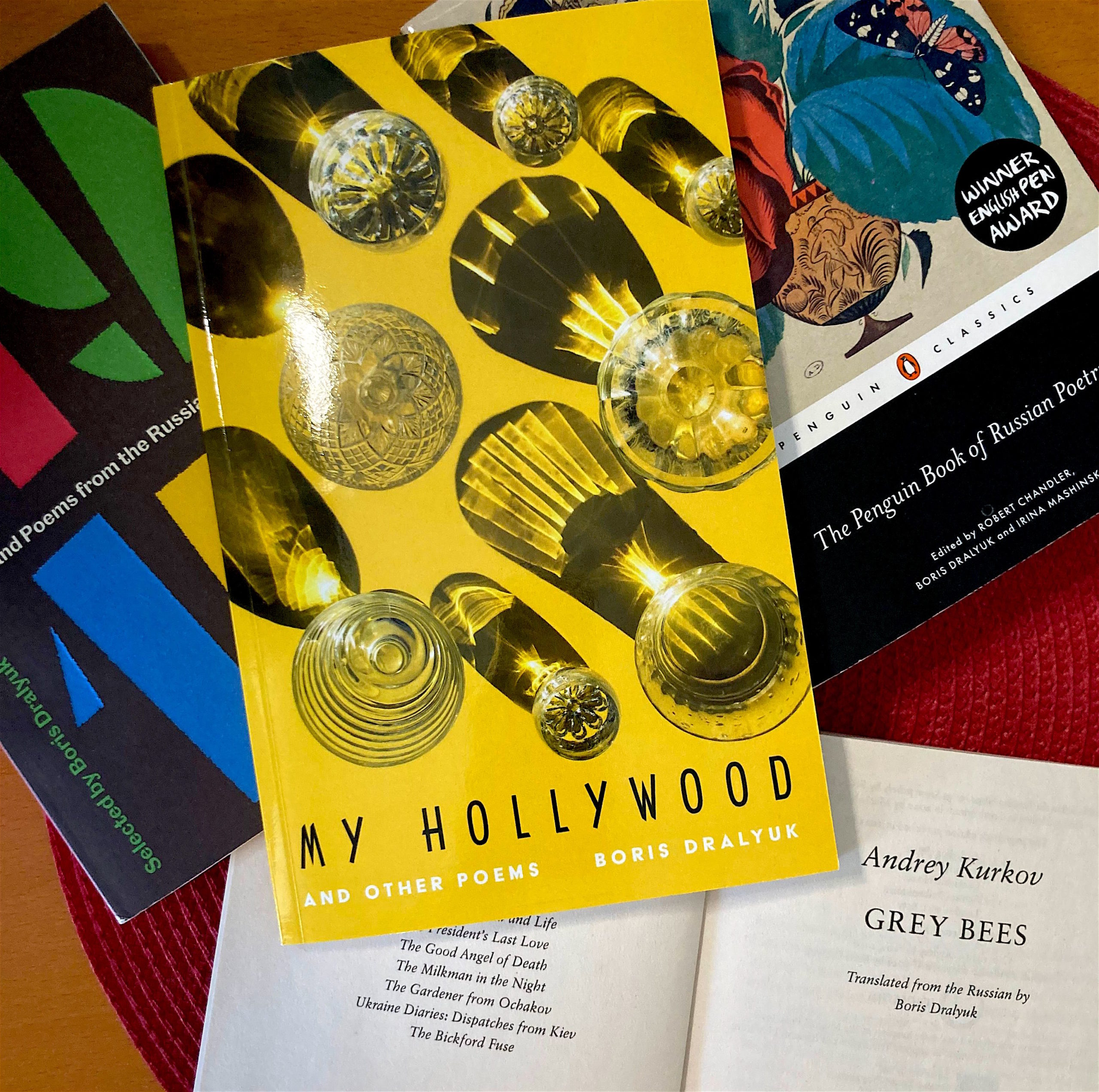

Thus I would posit that translation is (as I have written in the past) more than sympathy, but a true act of empathy, for translation engages the imagination just as empathy requires, and both require active, directed integrations of intellect and creativity to achieve meaningful effect. Someone who understands this integration thoroughly is poet and translator Boris Dralyuk. Born in Odesa and later relocating to America, Dralyuk is currently the Editor-in-Chief of the LA Review of Books, and is married to acclaimed fellow translator Jenny Croft. He holds a PhD in Slavic Languages and Literatures from UCLA, where he taught Russian literature, though he also taught at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. Awarded first prize in the 2011 Compass Translation Award competition, he went on, together with Russian-American poet/essayist Irina Mashinski, to win first prize in the 2012 Joseph Brodsky / Stephen Spender Translation Prize competition. In 2020 Dralyuk received the inaugural Kukula Award for Excellence in Nonfiction Book Reviewing from the Washington Monthly. His work has been published in numerous magazines and journals, including Granta, The New Yorker, The Guardian, The Times Literary Supplement, and The New York Review Of Books. His book Western Crime Fiction Goes East: The Russian Pinkerton Craze 1907-1934 (Brill) was published in 2012; three years later, he co-edited, together with Mashinski and British poet/translator Robert Chandler, the immense Penguin Book of Russian Poetry (Penguin Classics, 2015), containing a wide swath of poets and writers from the 18th to the 20th centuries. Dralyuk also served as editor of 1917: Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution (Pushkin Press, 2016). His translation of Sentimental Tales (Columbia University Press) by Russian writer Mikhail Zoshchenko was published in 2018. Dralyuk has also translated the works of Ukrainian writer Isaac Babel (1894-1940), with Red Cavalry (Pushkin Press, 2015) and Odessa Stories (Pushkin Press, 2016). The writings of Babel, a fellow Odesa native, were described by The Guardian’s Nicholas Lezard in 2016 as “(f)ractured, jarring, beautiful, alive to humour […] they have the ring of contemporaneity, and probably always will.” With bold strokes and wild energy, Babel vividly explores the lives of an assortment of colourful sorts drawn from real life, and Dralyuk’s own poetic attention to tone, colour, and pacing shine through the words, not to mention the meticulous, carefully considered rests between those words; rhythm, as it turns out, is just as important as exactitude. In addition to translating the work of Babel, Dralyuk has a close association with noted Ukrainian author Andrey Kurkov (b. 1961), whose equally timely and often harrowing books The Bickford Fuse (Maclehose Press, 2016), and Grey Bees (Maclehose Press, 2020) have been translated to much acclaim, with Kurkov’s own recent fame in the West fuelling a rising awareness of the centrality of good translation and all the moving parts therein.

After much planning and re-planning, Dralyuk and I finally were able to chat – about translation as it applies to various corners of culture, about so-called identity politics, the choices he’s made as editor of the LA Review Of Books, his debut collection of poetry, My Hollywood (Paul Dry Books, 2022), and about the role technology can (should) play in advancing the awareness and appreciation of languages. We also discussed current notions around expression of cultural identity; related moral panics; the value (if any) of retaining romanticized notions in art and music and the related role of context in breaking apart habitual webs of intransigence. Just what does Dralyuk think of the current (and perhaps lasting) labelling of identities? Certainly such labels matter in translation? In an essay from March, The New Yorker music writer Alex Ross noted that “(a)cknowledging the polyglot entanglements of the musical canon can, in fact, serve as a check on the oppressive allure of nationalist mythologies.” At a time when privilege, didacticism, and binary conclusions dominate large swaths of cultural discourse, examining the complex connections between familial (and social, economic, cultural) origins and creative output is vital, translators play a crucial role in helping to facilitate (and in some cases, promote) awareness and expansion of those connections, and of fostering curiosity, comprehension, and compassion to those identities.

And, a quick if vital note: I don’t speak or read the languages Dralyuk translates (yet), but I do strongly feel that his work, especially at this point in time, is of tremendous importance. Dralyuk possesses a musician’s approach to the elements, skillfully balancing, conjuring, and highlighting tone, colour, dynamism, texture, tempo, rhythm, silence, as pace and structure dictate. He understands the complexities of technique, the labyrinthe of contexts, the connections between head and heart, and he wants to let us, the reader, into that world. Emotion is, as you’ll read, a key part of what he does. Dralyuk is a maestro of translation, but he is also (and this was confirmed in our chat), humble, funny, kind, and involved. I remain grateful for his time and energy.

Note: The following interview was edited by Boris Dralyuk on 30 May 2022, following its original posting on 29 May 2022.

You’ve translated authors whose works are now more widely known, and you’ve taken part in panels on Ukraine; do you think the attention on the country and its authors will lead to an overall greater curiosity and knowledge?

You’ve translated authors whose works are now more widely known, and you’ve taken part in panels on Ukraine; do you think the attention on the country and its authors will lead to an overall greater curiosity and knowledge?

I think the attention is a good thing if it’s a lasting awareness.None of this is certain yet, whether this period of newfound fascination will outlive the conflict or whether it will even, frankly, be sustained throughout this war, which shows no sign of ending. I can only rely on my personal impressions and on the things I hear from my friends, but I think the worry is that social media and the news cycle bring up new scandals and new conflict and new conflagrations every day, and they have a lifespan of their own, and it would be wonderful if the people who are advocating for and spreading awareness of Ukrainian culture, if they’re able to leverage this attention that’s been drawn to the country – for the wrong reasons – for good.

Leverage the attention in a meaningful way that technology allows for?

That’s my hope.

Very often, I see – and I’m sure you do too – these updates and opinions go by, and I always wonder how it is that we don’t have a better technological framework that would accommodate the translations you and Jenny do.

I think Jenny is more of an optimist than I’ve tended to be. I’m pretty pessimistic myself, nowadays, but let’s put it this way: let’s say you have some degree of earned respect in the world, you’ve done a few things people like, and therefore you speak with some degree of authority. If that’s the case, what you put out there, regardless of the technological channels, will reach people. Social media is powerful in that regard; these things, even poems, if well-timed – and I don’t make a study of when to post or that kind of thing, though I know some do – but if well-timed in the general sense, if they hit on something people are thinking about, and you are one of the people to whom others tend to listen on these very subjects, the thing you’re putting out there will reach someone, a good number of people. Even if you reach two or three people when you could’ve reached five, you’ve still reached two to three people. I’m not really complaining about the channels available to us, I know there are people like yourself who actively work and think about new platforms and new ways to present the cultural items we care about most in a way that might gain traction.

These new ways of presenting culture tend to bump up against the perceived legitimacy of legacy brands, but the tools at hand, which everyone uses, make changing perceptions a challenge. Being independent means you gain certain things but lose others.

I’ve always prided myself on the fact that I don’t intervene too heavily in the things we publish at the LA Review of Books. I edit what we accept, if not myself, then others do, but it’s a broadly-based organization and always has been. The editing is not a reflection of my personal vision – I’m not Draconian, I don’t rule like a tyrant – but where I do rule like a tyrant is at my own blog or on my social media platforms, and I regard those as a rather pure form of expression. I have a very different sense of what a successful post on my own blog means to what a successful post on LARB means. Not infrequently a poem or translation published on my blog will reach more people than it might have at the LARB website itself – and that’s because people who believe that I do something well enough to listen to me go to the place where I do it; they’re not the readers of the LA Review of Books, necessarily – they’re the readers of my translations. And over time that number of people has grown, largely thanks to my use of WordPress and Twitter.

You are your own brand in that sense.

Yes, that’s right – because I’m not thinking of how to elevate my position there. I don’t get paid for my blog posts or the translations I post there. lf I really wanted prestige I’d try to get them into the major journals and would submit widely every 6 months, and face rejection letters and do it again and again – but that’s not what matters to me. I want those translations and those poems to reach the largest possible number of readers. And so they go on my blog.

And that’s to me a crucial point about the act of translation: you want to reach people. Reaching isn’t the same as engagement...

That’s very true…

… but through reaching people you can engage with what you translate in a new and important way. When I spoke with Elena Dubinets she said she found it hard to fathom how soldiers who’d read Dostoyevsky could engage in such horrendous acts of violence – which made me ponder the ways in which culture is received and perceived according to various factors.

I think if there is a net-positive outcome here, it is a change in how we perceive Russian culture. Some people do have a starry-eyed view of Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing, but I myself do not – but I don’t think it’s a crime to think that way. I do think it can become pernicious when we associate Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky and Pushkin, and their art, with a kind of purity of soul, and a purity of vision, and then assume that anyone speaking Russian must surely possess those innate qualities. That’s not a good thing. We have to be realistic, difficult though it may be. We can’t always hold ourselves to this, but we have to be realistic when we make judgments about cultures and the bearers of those cultures, whatever the culture we come from. We may love the US but hate our neighbour because our neighbour has this to say, and our mother has that to say, and the guy down the street says something else – we’re all very different, yet there are things that tie us together. The same goes for people living in Russia and living in Ukraine. At some moments those common features become the most important things in our lives – as in moments of crisis, moments like these – but in general we are all different people and all have different capacities for insight and capacities for love and capacities for hatred. Russian culture, being such a powerful force in the world, has convinced many people, too many people, that Russians are a bunch of soulful Tolstoys and Dostoyevskys and Pushkins, when Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky and Pushkin were themselves complicated figures, not pure of soul at all times. I think this war can make us more realistic, bring greater nuance to our understanding of the people we read and admire, of the cultures in which we’re interested.

The “nuance” aspect largely goes against the algorithms that power the platforms we use…

Yes!

… but now especially, do you feel a particular weight or responsibility to not just present new things but old things with that same nuance? And how much do you see others carrying it forwards?

I think anyone working in Ukrainian and Russian right now feels a heightened sense of responsibility. I know I certainly was much more likely to do things before this war because I was interested in them without thinking about their effect in the world. I was kind of an “art for art’s sake” purist… I mean, I have ethics, but I’ve always been interested in presenting the most … challenging, the most delightful, the most complicated, the most unusual work, in translation, regardless of the life of the man or woman who wrote it, regardless of their political affinities. It’s basically been my sense that if the work is well made, it deserves to be read, and people can make up their own minds about how terrible the person was or how terrible the things expressed in it are. I still think that’s largely where I land, but I feel I now have to be more selective, not because anyone asked me. The people I translated tend to be people who are, I think, generally, somewhat responsible – not always. But I do think that it behooves us to be careful, now, in how we present work that may be interesting but perhaps can be too easily misread or misused at the same time.

Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without express written permission.

I’m curious how you think this relates to the music world. It’s difficult to find good translations, even with companies dedicated to performing in English; there is this sense of “well just learn” whatever language – “just” carrying a number of unfair assumptions, not least access to resources. So how to most effectively move past these attitudes? And how do we approach translating things like libretti, which, by their very nature, resist any form of translation?

I think the technology is very much the answer. Google has taught people that translation is no easy thing, and Google Translate, yes, people knock it, but there are two things about it worth considering: one, it’s getting better every day, because of the input – every time someone asks it to translate something, it learns – and the other thing is that it reminds people every day of the need for a human touch. I think ultimately it’s a great educational tool, not only for getting the bare thing across, so some people can move about their business day, but also, if you plug in Tolstoy whole, you’ll get rubbish that’s useless unless a human being gets involved. The technology leads people to realize how important translation is. Over the last ten years or so there’s been a greater appreciation of the work of translators and that appreciation has inspired many young people – I see this every day, more and more people are asking me about my career and how I got into this. So there’s more interest in learning and mastering and communicating across languages, and the number of younger translators is growing by leaps and bounds, and that speaks to a broader interest in foreign languages.

That said, I don’t think this necessarily means the quality of translation will improve, because what you need in order to be a great translator is the ability to read very closely and very carefully, and with a lot of emotion. You have to respond emotionally to a text, and not just intellectually. You also have to have deep intellectual understanding, but you need a real love for expression – a real love for the target language. You have to revel in it and relish it. You have to find the task of writing immensely rewarding, find a lot of joy in it. People who translate simply because they love the original and are just going through the motions of putting it into English will probably not come out with as pungent or flavourful a product as those who both love the original and love the target language.

That brings to mind a common line of thinking on English: “oh it’s so limited…”

I hate that…

Really?

I really do, I hate it when people say, “Oh, well, English is a poorer language, because it doesn’t have a-b-c” – no, every language lacks something, an a, b, or c, but it makes up for that in other ways, by what it brings to the table. So you have to be in awe of the possibilities of English when you embark upon a translation – that’s how you get the best text. You don’t get it by saying, “Oh no, I’m going to lose this and that because English can’t possibly do it” – yes it can! English can do anything you want it to! That’s the attitude you’ve got to take.

By the same way of thinking, how would one translate the works of writers like Joyce or E.E. Cummings into Russian?

People have – you do it by writing Ulysses, by being a genius at your work. Those translators did a good job. That’s how Alice In Wonderland was translated into Russian – you have to have the same level of imagination and sense of possibility as Lewis Carroll had.

I love the Irish sense of playing with the language of their British colonizers – it’s a big reason I fell in love with Irish literature years ago, and underlines what Rexroth says when he explores Sappho, and gives examples of how each culture translated the same poem differently…

The Irish thing is a good example of what Ukrainians have attempted to do with the Russian language, from Gogol on – a good parallel –Isaac Babel would count, by dint of two circumstances, as a colonial subject –he’s Jewish and he’s from Ukraine. He’s a good analogy for Joyce, for speakers of Irish extraction. That’s one of the things I love most about translating the Russian language of Ukrainian speakers, which is a kind of endangered species now: they approach it from the side, as insider-outsiders, and it makes for very rich texts. I’ve spent a good deal of time on that aspect.

The insider/outsider thing is especially interesting – how much do you identify with that, as someone not born in America but raised there?

I think of myself largely as an American. So many of us weren’t born in America, and it’s a unique culture in that regard; nativism is present but isn’t the defining feature of the culture. Most of the people who have contributed mightily to the formation of American letters and culture, from the colonial period on,, were immigrants to the United States…

… which provides an interesting subtext to your “Hollywood” title of poems; it feels like a hat-tip to the many others artists who settled in that precise area.

Yes, exactly! I feel I’m a pretty good run-of-the-mill American – but yes, of course, you are also right that there is an outsider component to it. This happens to be a nation of immigrants, but that doesn’t make me anything other than an immigrant: I am still an immigrant to the United States. The story of immigration is central to the story of America, writ large.

That inclusivity stands in stark contrast to a world that quickly ostracizes those who don’t speak the language…

It happens, but I think that’s wrong – and to my mind, very dated.

It brings to mind what Rexroth noted, that translation is an act of sympathy, or to my mind, empathy.

Yes, and it’s amazing to me that that observation had to wait until 1959 to be made – I mean, it probably didn’t, I’m sure others said something similar – but it seems so natural to me that those who enjoy translation the most, the people who are the most successful at creating readable and moving texts based on texts in other languages, are using their capacity for empathy. They really do feel deeply connected to the texts they’re reading and to the people behind them. And if you don’t feel that connection, if you just sit there mechanically translating, then you may produce a more accurate version than Google Translate, but it won’t necessarily be a fuller version – or a more appealing one.

Your work has made me ask ‘who’s the translator?” through many book purchases the last little while.

That’s so lovely – that’s as it should be! I think Jenny probably did more to accomplish that than I did, but it’s important to pay attention to the translators. There are certain translators, long dead, whose work may not be perfect, but who I feel have as much of an oeuvre as that of any author, so I will read everything they’ve done, simply because I love their artistry.

That’s similar to following the work of soloists or conductors: one may not like a particular piece or opera, but one might really love the artistry of the person doing it.

That’s a perfect analogy! The soloist or conductor is an interpreter, just like the translator.

Speaking of translations and artistry: do you have a favourite translation of Bulgakov’s famous The Master and Margarita?

That’s a tough question. I think the Michael Glenny translation of 1967 is overall the more flexible and colourful, but there are glaring errors that have yet to be corrected. If somebody were to sit down, somebody who really understands the text, and use it as the start, building it out, then we’d have a masterpiece on our hands.

Because you haven’t done it yet…

I would love to edit that Glenny text, but process-wise, one way I check – it isn’t a perfect thermometer, but it works – how good a translation is, is by the impact it has on the target culture. For instance, it was the Glenny translation that gave us “Sympathy for the Devil” by The Rolling Stones. Personally, I don’t think the later translations would’ve had that influence – they’re not quite as readable as the Glenny.

I keep being told that there has yet to appear a translation which captures the humour, the rhythm…

I think that’s generally true. We’ve made a start, but we need someone to go in there and finish. Frequently I’m drawn to older translations not because they’re the most accurate in every sense, not because they capture all the tones of the original, but because the world in which those earlier translators lived is more or less the world in which the authors lived – they were contemporaries, so when the authors described something they could see with their own eyes, those translators of long ago saw those things with their own eyes too. When they were translating a description, they knew exactly what was being described. That creates a sharper image in English, a clearer sense of what it is Tolstoy is talking about, or Dostoyevsky is talking about. I would urge people not to toss out the old versions completely; you can continue to translate and refine the texts but I think those old versions have something to offer us too.

Like literary Ur-Text?

That’s right!

There is the urge now to make plain cultural labels – ie, “this is Ukrainian; that is Russian” and to draw pat conclusions based on them.

I don’t think people will hold on to that; I think it’ll go away. Right now there’s controversy about renaming streets in Ukraine. But renaming a street from Tolstoy Street has nothing to do with saying that “Tolstoy is a bad writer.” What it’s about – and this is spelled out clearly in a LARB piece – is saying: look, there’s every reason to keep reading Tolstoy; go ahead and read Tolstoy, no one’s stopping you. But there’s a reason this street was named after Tolstoy in the first place: this country was subjugated by Russia. The reason that we have so many streets named after Russian writers and none at all named after Portuguese writers is that we were not subjects of Portuguese colonization – we were subjects of Russian colonization. So by renaming these streets in honour of Ukrainian authors and cultural figures, all we’re saying is: these are our streets. If you want to sit on the street and read Tolstoy, that’s fine. It may not be a comfortable thing for those who love Tolstoy to witness, but it’s the choice of the people who live on that street. I really don’t think this hysteria about Russian culture being cancelled will be proven to have been justified. There are a lot of reasons why we should worry about all the things happening now; the fact Russian literature will lose a few more readers in the short term is not one of them.

A couple people have written to me to say, “It’s not the time for Russian voices,” and I myself have shown preferential treatment for those writing from Ukraine – it’s more important right now. People will make that kind of editorial judgment call. Yet I can’t imagine any person, no matter how patriotic they are who will say, “I will never again read anything from a Russian, ever” –even those who are militant say, “It may take five years, or ten years; it may take twenty years,” – but at some point, I think Ukrainians will be reading Russian literature, and Russians will be reading Ukrainian literature. Right now, it makes all the sense in the world to listen to Ukrainians who are under active attack rather than to most Russians. That said, I still translate Russian authors myself; I just did a translation of a piece by Maxim Osipov (“Cold, Ashamed, Relieved: On Leaving Russia“, The Atlantic, May 16, 2022). But, to be blunt, I don’t think Russians are paying that big a price, comparatively – that’s my sense of things.

Elena Dubinets also noted in our chat how the language around how we discuss these cultures must be decolonized – a word that’s been used more and more often in this context.

Yes, and decolonization is not necessarily cancellation. Again, all we’re talking about is adding nuance to our understanding of how Russian culture functions, and has functioned, and been allowed to function, in the world. Tolstoy himself is one thing; a monument to Tolstoy is another. A monument to Tolstoy on his estate is one thing; a monument to Tolstoy in a place he never visited, simply because Russia owned it, is another.

But this questioning has led to a big moral panic in some circles – certain corners of the classical world have made quite a lot of noise about how identity politics is detracting from art and music. For instance, Prokofiev was born in Eastern Ukraine; Tchaikovsky’s paternal family were Ukrainian. What do you make of the current debate around identity politics as it relates to Russian and Ukrainian artists?

I don’t think this is identity politics – I think this is the acknowledgement of the complicated histories of this region and of the people who called and still call it home. To say that Gogol is strictly a Russian writer or strictly a Ukrainian writer would be silly – he’s obviously a Russian writer and a Ukrainian writer, and that’s a consequence of the complicated relationship between Russia and Ukraine. I think we as lovers of culture can arrive there – many of us are already there. Right now tempers are heated, and for good reason: cultural monuments are being destroyed by bombs. The head of Shevchenko has a bullet in it.Those things are not acceptable; those things are not going to bring about truth and reconciliation. But I do feel we’ll get through this. Both of these cultures are too strong to be eradicated, and no matter how powerful the Russian military is, it will not squash Ukrainian language and Ukrainian culture. which was banned over several centuries yet lives on, and is one of the most productive literary cultures in Europe right now. I don’t think anyone who aims to kill the culture as part of this conflict will succeed, and once they’ve failed decisively, we can go about creating a better, more representative picture of this region’s history, and its art.