Nationaltheater, Bayerische Staatsoper. Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Anticipation, excitement, and anxiety tend to be usual feelings in relation to new productions, for artists and audiences alike. When the opera being staged is a favored work, those feelings become distinctly pronounced, and call into question the whole nature of fascination with the piece, the composer, the librettist, and the art form overall. As a pseudo-knowledgeable, ever-studying, non-singing, over-wordsy, wide-eared opera person, you may become conscious of your love, others’ love, your expectations, others’ expectations, your preconceptions, others’ preconceptions, your reactions, others’ reactions – and you may find yourself exhausted by the conscious, semi-conscious, and unconscious levels of identification, non-identification, meditations, musings, and various analyses you perform, repeatedly, over the course of weeks, months, years. You may hear bits of arias and orchestration at unexpected moments, and tap your foot or teeth or waggle eyebrows or fingertips along, an internalized melodo-sensual-rhythmical complement at all hours of the day or night: in the bath, out on the street; looking out the window at a white dog, looking up in wonder at a purple-pink orchid; frowning in a mirror, forking in cold spaghetti, falling asleep in front of the telly. You may wonder and worry about those new costumes and sets and what form of fancy choreography might complement some favored passages, to say nothing of all the secret, conversational places between. You also ponder why any of this should actually matter amidst a year-long worldwide pandemic. Yet it does, and very much; art takes on new and precious significance amidst pandemic, more so when there is the willpower to see it realized in a live form. Anticipation, excitement, anxiety; soap, rinse, repeat.

And so it is with a new production of Der Rosenkavalier set to make its debut in Munich this coming Sunday. Premiered in 1911 in Dresden, the opera is associated with a distinctly Rococo visual, helped along by celebrated recordings and fusty album covers as well as the famous Otto Schenk production, first presented in 1972 and led by Carlos Kleiber. The wigs, the dresses, the buttons, the buckle shoes – the glitter, the gilding, the glamour: these are the elements co-related (however consciously or not) with Der Rosenkavalier. There was more than a hint of public mournfulness when the Schenk production was retired in 2018. New visions of old favorites tend to create waves, sometimes (/ often) brushing against the sandcastles of expectation lining the shores of creative consciousness. It’s difficult to gauge how any new production will be ultimately received, but in an environment so heavily re-shaped by pandemic, it’s little wonder that a new staging will court reaction, for after all, certainties within the artistic sphere are nice (or perceived to be so) in an age where there is naught but uncertainty everywhere else. “Give me my buckle shoes,” goes the thinking, “they hurt to walk in but they’re comforting nonetheless.” Such clinging can, of course, lead to needless suffering; bunions are not marks of virtue, after all. Sometimes a good dose of curiosity is the best (and only) thing to provide a proper shoehorn. Yes, it’s frightening to stay open at a point in history when it feels so dangerous on all fronts – but in the current cultural climate, that openness seems more vital than ever.

Certainly good leadership can help to encourage the needed spirit. The determination of the Munich team behind the new Der Rosenkavalier, together with actionable choices which manifest such determination, have provided much inspiration and hope. Directed by Barrie Kosky, conducted by Vladimir Jurowski, and designed by Rufus Didwiszus, the new production was birthed in an environment characterized by rules and restrictions which would have seemed like a form of creative straitjacket only 14 months ago; now that straightjacket is a parachute, the very thing which allows for any sort of a view. Hugo von Hofmannsthal wrote, in Buch der Freunde (Book of Friends), his 1922 collection of aphorisms, itself a kind of postmodern conversation with artists of the past (the title is lifted from Goethe’s own West-östlicher Divan), “(t)here is more freedom within the narrowest limits, within the most specialized task, than in the limitless vacuum which the modern mind imagines to be the playground for it.” (trans. Tania and James Stern; The Whole Difference: Selected Writings of Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Princeton University Press, 2008) Like every event currently unfolding (or planned) at various houses operating at various levels in Europe, this Rosenkavalier conforms to current Bavarian health regulations, ones which (as you’ll read) entail a strict system of interaction for artists.

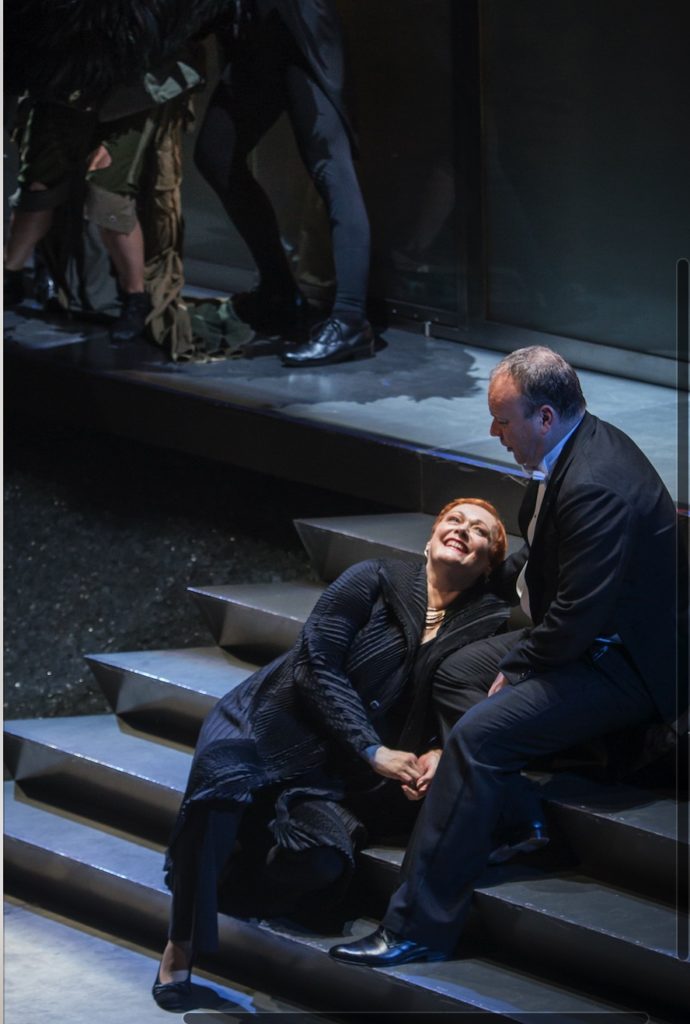

Marlis Petersen (L) as the Marschallin and Samantha Hankey as Octavian in a scene from Barrie Kosky’s staging of Der Rosenkavalier at Bayerische Staatsoper. Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Such a conformation also means that Strauss’s original, immense score isn’t going to be presented (at least this time), but a reduced version of it, by conductor/re-orchestrator Eberhard Kloke, will; with its dramaturgical approach, Kloke’s reorchestration utilizes the sound palette of Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos (which premiered the year after Rosenkavalier, in 1912) and, notably, makes no deletions to the original, as has been the case with past presentations and recordings. Hofmannsthal’s libretto, filled with a delicious syllabism, mixes intimate poetry and epic theatricality (including broad farce) within a dialectical framework involving the Marschallin, her young lover Octavian, her obnoxious cousin Baron Ochs, his intended bride, Sophie (who falls for Octavian, and vice-versa), her status-obsessed father Faninal, and, I would argue, the immense if unseen character of the work, the Marschallin’s husband. The opera’s final scene features one of the most famous trios in all of opera, but each part could (does) stand as its own form of soliloquy, a moment whereby Octavian, Sophie, and the Marschallin are enacting a hoary old romantic cliché (the love triangle) whilst forming something new, as, from word to word and note to note, they individually express and refine their sense(s) of freedom, circumstance, choice, and actual, felt consequence. “Es sind die mehreren Dinge auf der Welt, so dass sie ein’s nicht glauben tät’, wenn man sie möcht’ erzählen hör’n. Alleinig wer’s erlebt, der glaubt daran und weiss nicht wie,” sighs the Marschallin. (“There are so many things in the world that one would not believe them if one heard them told. Only those who experience them believe in them, and do not know how.”) Every time I hear this, no matter the recording, I want to run across a dark beach barefoot, leaving wig, corset, and buckle shoes behind, kicking the sandcastles as I go.

Sunday’s presentation in Munich is new in not only the approach to staging but in its casting, with many here making important role debuts. Marlis Petersen, celebrated for her interpretations of Lulu and Salome, debuts as the Marschallin; mezzo soprano Samantha Hankey sings Octavian, the “cavalier” of the title, while soprano Katharina Konradi is Sophie, the recipient of the cavalier’s “Rose.” It was a true a privilege to speak with the latter two singers the day after their first general rehearsal, with the artists carrying an ebullient energy from the experience, their first in front of an audience (however limited) after a long period of deprivation. Both artists have extensive experience across celebrated opera stages, and with singing the music of Strauss. Soprano Konradi is currently a BBC New Generation Artist (2018-2021), and has made numerous recordings for BBC Radio 3. From 2015 to 2018 she was a member of the ensemble of the Hessisches Staatstheater Wiesbaden, and joined the ensemble of Staatsoper Hamburg at the start of the 2018-2019 season, during which time she also performed as Zdenka (in Strauss’s Arabella) at the Semperoper in Dresden. She has enjoyed concert engagements with Orchestre de Paris, the Tonhalle-Orchester Zurich, Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, and NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra, to name a few, and worked with a range of conductors including Daniel Harding, Manfred Honeck, Kent Nagano, and Paavo Järvi. Along with performances at Wigmore Hall last year, Konradi has a new CD of lieder out now, Liebende (or Lovers, Avi Music), featuring the music of Strauss, Mozart, and Schubert. This summer, restrictions allowing, she’ll be performing in Tobias Kratzer’s staging of Tannhäuser. Mezzo soprano Hankey is a member of the ensemble of Bayerische Staatsoper, where she made her role and house debut as Hänsel in Hänsel and Gretel in late 2019. A former member of San Francisco Opera’s Merola Opera Program, she has sung at the Metropolitan Opera, Opera Philadelphia, Opernhaus Zürich, Den Norske Opera, and is the recipient of numerous awards, including the Birgit Nilsson Prize (part of Operalia) for her interpretation of the music of Strauss. She’s worked with numerous conductors, Philippe Jordan, Gianandrea Noseda, Nicola Luisotti, and Carlo Rizzi among them, and this summer performs in Andreas Kriegenburg’s staging of Das Rheingold as part of the Münchner Opernfestspiele, the annual summer festival via Bayerische Staatsoper. The event, as with Bayreuth, and so many cultural events, depends entirely on which restrictions may (or may not) be in place as the result of coronavirus infection rates.

Der Rosenkavalier streams live from Munich on Sunday, March 21st, at 3.30pm CET.

Katharina Konradi (foreground) in a scene from Barrie Kosky’s staging of Der Rosenkavalier at Bayerische Staatsoper. Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Does everyone working at the Staatsoper receive regular testing?

SH Yes, the opera has a whole bunch of safety procedures in place in addition to regular testing and mask-wearing; everyone in the house is sectioned off into groups. Performers are at a specific level of risk, the red group it’s called; your group determines the level of interaction you are allowed to have with other people.

Samantha’s recent Bayerische Staatsoper Instagram takeover showed a bit of this testing process but also featured Katharina on her trampoline at intermission.

KK Oh, I take it everywhere! Whenever I have performances, concerts, projects like this, I make a recording, whatever, I take it with me, and I relax before performing with it. I don’t know how to quite express it, but my body is like waves, so I’m so happy to have it.

It’s a good way to keep your energy up – literally.

KK Yes it is! It’s fun to do before a performance.

SH You also have a balancing circle, what’s it called?

KK Ah yes, a balance board…

SH I always want to come into your room for it, it moves in all these different ways – very cool!

Working in the current environment must be quite different from what you are used to.

SH We haven’t performed in so long. I think Barrie saw we’re young, fit people and we like to move, and so…

KK I think the big difference is that we don’t have an audience. Yesterday we had a general rehearsal and we had fifty or sixty people watch, and it was completely another scene, because you know there are people sitting there, and you can send the energy to them and you also take a small part of this energy to you on the stage. It was a great experience after this long time without an audience.

SH Hearing applause at the end was so unexpected, we were like, “Wow, this is … incredible, this is people’s way of saying “Thank you for doing this.” It was very emotional. I didn’t anticipate hearing applause.

I’m reading John Mauceri’s Maestros And Their Music (Vintage, 2018) and one of the things he writes about is how audiences and artists are in partnership; how has that idea played into your experiences?

SH In rehearsal there would be some laughs from the artistic personnel, and yesterday I was thinking, “Will (the audience) laugh here? Am I not hearing laughs because of the masks? Is this working? Are you enjoying this?” That’s the difference between having fifty to sixty people and having absolutely no one. I think of it as this double-sided coin, though, because you can also do so much without an audience – you feel safe to explore and play and make the most of it, even though it’s being streamed to the world. Digital isn’t a replacement for live performance but it’s the best option we have right now.

What’s it been like working on this with Barrie Kosky?

Katharina Konradi (Photo Simon Pauly)

KK For me it was a surprise – Barrie gives us the ability to be free on the stage, and to find things, by ourselves. For me it was the first time for this kind of experience, I was like, “What should I do?” And he said, “You can do whatever you want and I will say if you are right in your character, in your body, and in what Sophie is like.” It was, for me, the first time the stage director doesn’t say something before to the effect of, “Sophie is like this and like that, and so you must be like this.” I felt really free to build my character. He just put in small corrections, like, “You can be younger and laugh and be excited” but it was not like a set frame, with no possibility to take my own experiences into this role. And that’s been fantastic. I think this cast is full of personality and full of people who are so different and we are not all alike, we all have imaginations. Barrie never dictated how we should be, so we are allowed to use that difference. Every time in rehearsal we are trying to find some new aspects to take into our characters. I don’t know how it was for Sam, because she’s on the stage all the time. Maybe it’s different again…

SH I think, like what Katharina said, it’s been completely liberating working with Barrie. We’re doing such major roles that have such incredible history; you know, so many great singers have done these roles, and they’ve been in these iconic productions that we’ve all seen…

… may I add here, it is Christa Ludwig’s birthday today…

Samantha Hankey (Photo © Famous)

SH Oh, what timing! So yes, there’s so much weight in terms of that whole history, and, I don’t want to say fear, but it’s a huge amount of responsibility in doing these roles, and seeing all the traditional productions you think, “Okay, they follow the exact Hofmannsthal style and directions” and “This singer did it *this* way” and “Well this is how it’s always been done” – and Barrie said, “We want to do something different here.” So that means we get to do our own versions of these characters. In a piece like Der Rosenkavalier there aren’t a lot of variations in terms of interpretations of the piece – there’s a set type of Sophie, there’s a set type of Octavian. And now I really feel we’re creating something new that still honors this libretto. It’s very real.

In that vein, you are singing a reduction of Strauss’s score by Eberhard Kloke right now; some have expressed doubts about the sound world of Strauss undergoing such a transformation…

SH … well we can either not have art during the pandemic or we can have music in a reduced form and stream it, or we can all stay home. What’s preferable?

KK In this orchestral form, you can hear different things – for instance, a piano playing through our conversation. It’s better to perform like this, than to stay at home.

… and this Kloke version seems like a theatre piece in its own right, with a dramaturgical approach, and the sound palette of Ariadne auf Naxos. What’s it like to sing in such an expansive space?

KK For me and for Sam, it’s the first time we perform these roles. I don’t have experience with a full orchestra in this piece, I know only a bit and I know recordings from the past, but I think it’s a great experience to start with this orchestration, this not-so-big sound… but now the sound *is* really big because the orchestra is not in the pit but on the regular level. It’s a special experience, to take this sound, in a reduced form right now – like a child, we start with the small and then grow, and the role will be growing also, and in the next year hopefully it will be with the full orchestra.

SH I think it’s a great warm-up for when we do it with a full orchestra in the pit. Right now in an empty house the orchestra, already with its 36 to 40 instruments, is huge, because they’re placed on the orchestra level, so maestro and the team have come with ways to deaden the sound a bit, especially under the woodwinds and brass section, but with no one in house to absorb that sound and with our very boomy set, the sound is crazy. The Staatsoper is meant for bodies, for people to be there to absorb that sound and for the orchestra to be in the pit. But it’s a good compromise and a good way for us to warm up to these Strauss roles.

This being your first time doing these roles, how have your perceptions of them changed through rehearsals?

SH These are real people – the fact we’ve taken them out of this traditional Rococo style and thrown so much life and color into the characters, I think, means they’re very relatable and, I don’t want to say modernized, but a lot of the stuffiness is just gone, at least for Octavian.

KK For me it’s also really been freeing. I tried to find my own character in the (depiction of) Sophie. So in the normal life I am not like a “lady” – I can also be like a child, so I took this part of life onto the stage. In the old recordings, everything is really formal – “you must be like this” and you have rules (for the character’s portrayal) – we threw it all over and we can do, actually, everything. So we can be alive and and find ourselves in these roles.

(L-R) Marlis Petersen as the Marschallin, Christof Fischesser as Baron Ochs, and Samantha Hankey as Octavian/Mariandel in the new Bayerische Staatsoper production of Der Rosenkavalier. Photo © Wilfried Hösl

That points ups something said in the recent video interview, that even with a fantasy element present, the emotions are nonetheless authentic. How do you find that in a role like Octavian?

SH There’s so much curiosity in the character. For instance, you’ll see in our production we do a very different Mariandel than what anyone’s prepared for, I think, and it’s really so much fun. Octavian is so in control, and he is so not afraid; he’s young, and very curious. I take a lot of inspiration (in characterization) from what’s going on in the current world, in terms of him being slightly androgynous, perhaps gender curious – there’s so much room within these roles to explore what’s in the libretto.

Samantha, you’ve sung Cherubino (from Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro), which is also a famous trouser role. Do you see a connection?

SH No, I have to say; I think Octavian is very different to Cherubino.

People think of Mozart as a massage for the voice; I’m curious how Strauss has been for your voices through this era.

SH I spent the entire pandemic doing work personally – for myself, and in preparing to sing Octavian. That’s really all I did. Sometimes I see these questions put out there online – “What would you have done differently if you could go back to March 2020?” I’d do the exact same thing; I really prepared physically to get in shape for the stamina I knew I’d need for this, and put my heart and soul into the role and toward knowing everything I could about the music. I don’t feel like vocally it hasn’t gone well. But I kept hoping we’d get to the point of rehearsing this and put it onstage, and we’ve been very lucky to do that.

KK It’s a strange thing, when people in this pandemic era don’t use their time to develop the voice, to try something, to practise. So I work every time through this period, and I can say the same thing as Sam: I feel really fit, and I worked for this role. And I’ve done this CD recording (Liebende); I tried to do as much as possible, because in normal times I didn’t have so much time for other projects. Now I can practise every day when I want, with calm, and I can take a lot of time with things. And Rosenkavalier, it’s like a cherry on top of the cake, to be able to do this, to present our ideas and our voices in this production.

SH Of course there are times when the inspiration hasn’t been there, it would go on and off. Some days you don’t feel like singing, sometimes because of a gig that got cancelled, but really, for me, it was holding on to hope we’d get to February 1st and start rehearsing. I said to everyone in the room that very first day, “I’m just happy we’re here today.” With all the lockdowns and restrictions, you never know, so every day has been a gift we can go to work. The whole process of working with Barrie and Vladimir and the entire cast has been really inspiring, and creatively very restorative in the sense of wanting to work on other projects once this wraps up.

I would imagine being around each other has also been very good; as arts people it’s important to have the energy of others in a sensual, not solely virtual, way, and to have the knowledge you’re doing something new as well.

SH To be together and to create something so beautiful as this production has been special. As Barrie has said, art needs to be a reflection of the times – he also said something like, “I don’t want my productions shown after ten years” so as an artist, getting to create something new, it takes so much of the pressure off, because we can be ourselves, and be entirely present. We just take it one day at a time. As an American working in Germany I feel really fortunate, but for the majority of the pandemic I felt I shouldn’t’ be going in the opera house at all, that I’m really not an essential worker, but through rehearsing this piece, I felt like, “This feels important, this feels like it has meaning.”

Katharina Konradi (L) and Samantha Hankey (R) in a scene from Barrie Kosky’s staging of Der Rosenkavalier at Bayerische Staatsoper. Photo © Wilfried Hösl

I’d say you are an essential worker, at least to some of us. Lucas Debargue said recently how culture has suffered through the pandemic, but art and artists have (or will) become better.

SH I’d agree with that, but I also don’t think the arts were ever prepared for anything like this. You always think, “This is going to happen, it’s in the diary” and then for your whole world to be shattered… you don’t know if things are going to happen in the future at all. So again, I feel lucky working in Germany.

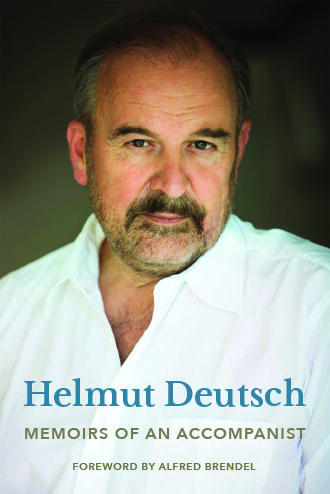

Helmut Deutsch and I discussed how perhaps the quality of listening has improved, how that’s a very valuable thing to have emerged from this era.

KK For us, because of this situation… yes, but also, when just one listener is in the house, as a performer you’re so happy. In normal times, when the auditorium was full of people, it was just another normal performance for us, but now, with just one person, you are *so* happy to see him or her, and you have another sense entirely of what you are doing, and for whom you are doing it.

SH And audiences have been silenced as well.

Yes, but not all people have the quilt of culture woven into their lives in the same way…

SH That’s why opera becoming digital is important. Not everyone has the luxury, once this pandemic is over, to travel to see performances. I do think this time has provided a big step forward for the industry to get with the times and have more digital content.

KK I think there is another side of this digital thing. I’ve done a lot of concerts in this pandemic time, and every concert, or almost every one, was recorded, and sometimes you don’t feel like, “I’m a singer of the world” and sometimes you also don’t do a very great performance, and in this time all the performances are recorded, so it’s like, “Okay, I must concentrate / I must be here and now / I must do it perfectly”…

How much do you think that expectation of perfection and the related pressure highlights the nature of digital then?

SH It is a bit stressful going into the livestream knowing that there will be imperfections, because art is imperfect…

KK I will say, I am a bit nervous about the presentation of the rose scene and how it will be filmed…

SH Oh, I don’t think they’ll do an extreme close-up then… and really, you sing it so beautifully, Katharina. I do think the atmosphere we create in the theatre might not transfer to the filming; the sound we make in the theatre might not be beautiful in recorded form, even though it was or is good in the house it’s designed for. But again, I still think it’s a better alternative than nothing. And I think listeners also understand that and can try and see past it. That’s my hope.

Photo: Katharina Konradi

Your memoir is especially notable for its candour; that’s a refreshing quality.

Your memoir is especially notable for its candour; that’s a refreshing quality.