|

| Stephen Hegedus and chorus members in AtG’s Messiah Photo: Darryl Block |

Handel’s great Messiah is associated with many things: ceremony, contemplation, a quiet joy. One thing it is not widely noted for is playfulness. That’s just where Toronto’s Against the Grain Theatre comes in. The company, known for their creative updates of opera works, is currently presenting a reimagined Messiah at Harbourfront Centre, one that fuses theatricality and musicality, and riffs off many moods: anger, fear, joy, rejection, abandonment, and… fun.

What makes this Messiah so special is the extent to which intimacy works as a strong, spicy partner to the essential grandeur of the work, which was composed as an oratorio and first performed in Dublin in 1742. Generally presented with an orchestra and soloists on a large stage, in a church, concert hall or auditorium, Against the Grain’s Messiah uses the audience as an integral part of the production, allowing us to experience the music in a closer and more revelatory way. At one point the chorus, divided by gender, fills the aisles on either side of the theatre and immerses the audience in a cascading waterfall of harmonies; it’s as if the God-made-flesh tale is being paralleled by the singers via musical metaphor, the heaven-to-earth connection made real. During the famous “Hallelujah” chorus, the ensemble is again in the aisles, singing and urging members to stand. (Some audience members at the performance I attended even proudly and loudly sang along.) Immersion and interactivity are not unusual for Against the Grain productions; their successful show #UncleJohn, a re-envisioning of Mozart’s Don Giovanni (produced in Toronto last winter) placed the audience in the middle of a wedding reception, with the action in the libretto unfolding with a delicious immediacy. What makes stagings like these so special is that one gets to experience the singularly unique experience of opera singing mere inches away, as opposed to several feet; the stage isn’t formalized, the performers aren’t distant. This choice of presentation has the effect of bringing the work — perhaps previously considered starchy, unapproachable, snobbish – into close relief, allowing an experiential understanding that frequently moves beyond the verbal. In Messiah, such an understanding approaches the divine, but it skillfully integrates an earthy aspect that is at once highly inspired and deeply moving.

|

| Andrea Ludwig and Owen McCausland in AtG’s Messiah Photo: Darryl Block |

While many symphonies program the Messiah this time of year (some featuring creative re-orchestrations), Ivany and Music Director Topher Mokrzewski make elegant use of a small ensemble to showcase ideas around beauty, spirituality, and play, within an intimate and ultimately enriching context. With an eighteen-piece orchestra and sixteen-person chorus, the work’s two-and-a-half-hour running time flies by, moving seamlessly through the various stages of the life of Jesus Christ. The work opens with tenor Joshua Davis carefully moving to Jennifer Nichols’s highly stylized choreography, eventually draping himself (in a rather impressive back bend) across a block. The music that accompanies is mournful and stately; as the work progresses, the musicians and performers onstage develop a synergistic chemistry that allows an equal and vivid exchange of energy that extends to the audience. Ivany features some nice meta-theatrical moments, throwing off the formalism of the work and its starchy classical associations. Tenor Owen McCausland removes his suit jacket, bow tie, shoes and socks near the start of the work; the female soloists (alto Andrea Ludwig and soprano Miriam Khalil) follow suit, their draping skirts revealing puffy layers of tulle beneath. The entire chorus and four soloists (including bass baritone Stephen Hegedus, who performs his own kind of strip-down later on) are barefoot throughout the production, despite their formal wear, pointing at an earthy experience, free of past constraints in either music or religion, though to some of course, they are one in the same. This Messiah doesn’t let you forget that.

|

| Joshua Wales in AtG’s Messiah Photo: Darryl Block |

The color scheme employed throughout the work is expressed via the rich, wintery tones of the dresses and suits — it’s a blend of wine reds and aquamarine blues — and helps to offset the stark, near-clinical simplicity of the set, which is composed of a few white blocks on a black floor. These blocks — picked up, carried, lain across, stood upon — resemble recognizable shapes (a cityscape, furniture, oversized toys) as different passages of music are performed; at one point, two tall rectangular shapes resemble nothing so much as the fallen World Trade towers, while at others, they’re a plinth for statuesque bodies and sensuous fabrics. Ivany marries Handel’s score with striking visuals to create a kind of Rorschach Test that integrates Baroque sounds and contemporary performance, where narrative is entirely secondary —or more specifically, non-existent. Ivany trusts his audience enough to allow us to to knit together the various fragments of the work. As opposed to emotional dictation, Ivany and AtG have opted for imaginative individuation, with elements of potential meaning (or non-meaning, in the form of pure experiential beauty) poking out like welcoming tentacles from a much older body.

The idea of “playing” — playing music, playing games, playing with each other, playing with notes, playing with ideas and identities — takes on huge significance in Ivany’s vision. As I’ve written about before, play is something I believe is central to creation; the act of play itself is akin to taking a ride on a highway of experimentation and imagination, and with Against the Grain’s Messiah, it’s given a robust workout. The famous passage “All We Like Sheep” is done with members of the chorus in a circular “flock,” shuffling back and forth across the stage, warily eyeing soloist Stephen Hegedus, who haplessly bleats out a few “baaaahs” after the chorus sings the title, as if against his own will. Watching the scene unfold, I couldn’t help but be reminded of a few pop culture corollaries; it’s strange to think of cartoons and puppets when one is watching a classic oratorio, but then, why wouldn’t you? Against the Grain seems to welcome these kinds of associations, and to see them as valid as references to Nordic mythology and gypsies. Why should classical culture be strictly self-referential? Surely a fusty insularity doesn’t help its broader appeal; a bit of pop culture might be just the thing — and with it, a bit of playfulness.

|

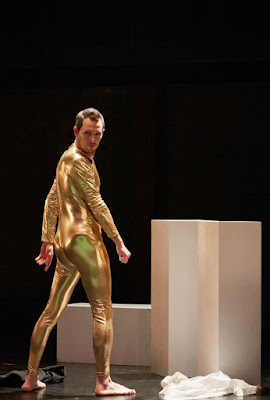

| Stephen Hegedus in AtG’s Messiah Photo: Darryl Block |

It’s that very sensibility, of playfulness fused with a kind of pop culture knowingness, that permeates one of the most memorable scenes in Messiah, which that occurs during “The Trumpet Shall Sound.” Stephen Hegedus, last seen for Against the Grain in their summer production, Death and Desire, jauntily delivers in his signature rich, robust tone, before stripping down to a gold unitard, striking various statuesque poses, and gleefully tossing glitter. What a refreshing contrast to his dour, serious expression in earlier scenes, and what a wonderful way to physicalize the joyousness of this passage! Dr. Frank-n-furter would surely approve, as would the travelers on the Priscilla. Ivany brings a fresh approach and wonderfully experimental spirit to each of these theatrical scenes, making Handel’s rich and (to my ears) sometimes dense score a highly digestible, vibrant, and yes, playful piece of music-performance art that suits the tone and tenor of the times, to say nothing of the direction opera and live performance may be moving in. By the end of Against the Grain’s Messiah, you feel buoyed by the energy, moved by the intimacy, and inspired by the sheer imaginative bravado it took to bring this piece to vivid life. Baroque music: ballsy, brave, and… fun? In AtG’s hands, you bet. Bravo.