One of the more engaging works I’ve read this summer concerns a seemingly-crusty topic, albeit with a very soft core: the music of the GDR (or German Democratic Republic), specifically mourning music, and the ways in which that music and its composers are remembered – or not. Founded in 1949 and dissolved in 1990, East Germany is, at least in the some quarters, very often associated with cartoonish images, frequently manifest in the form of glowering villains in grey suits and/or leather coats, breezily presented in Western popular media throughout the 1970s and 1980s, even into the 1990s. At the other end of the spectrum, the rising tide of ostalgie has made it equally hard to gain a proper picture, with the GDR’s more unsavoury elements glossed over in the name of sentimentality. Having an interest in GDR-born composers myself (Georg Katzer (1935-2019) and Paul Dessau (1894-1979) among them), it seemed like some form of fate to come across Martha Sprigge’s Socialist Laments; Musical Mourning in the German Democratic Republic (Oxford University Press, 2021) earlier this summer. Surveying various aspects of musical expression in post-WWII Germany (theoretical, practical, political, social, historical) and their intersections, Sprigge, who is Associate Professor of Musicology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, presents a fascinating portrait of specific creative expression, and its performative manifestations, amidst the time before, during, and after (however briefly) the time of the Berlin Wall. It paints a multilayered portrait of a time, place, and people that is at once difficult and diffuse, but just as equally heart-rending and human. Also, rather refreshingly, the book comes with its very own playlist, complete with performance suggestions, in its opening pages.

Organized not solely via strict historical chronology (the end of the Second World War and onwards through the socialist era), Socialist Laments is driven by memory – its perceptions, presentations, manifestations, and, by the actual act of remembering itself: the meaning, in micro and macro ways, in post-war, post-communist, and ever-creative senses. The idea of ruin, literal as much as figurative, casts a defining shadow throughout the book, past its opening explorations of the bombing of Dresden and related figures whose works had resonance in post-war times (among them choral conductor/composer Rudolf Mauersberger and his Dresdner Requiem from 1961), concentration camp memorials (including Tilo Medek’s controversial Kindermesse zum Gedenken der im Dritten Reich ermordeten Kinder / In Memory of of the Children Murdered in the Third Reich, 1974), Soviet influence (the apparent appropriation of the Russian funerary hymn “Immortal Victims” being but one example), the role and continuing function of the Kreuzchor in religious and cultural life, as well as anti-fascist expressions of the 1960s and 1970s, with reference made to the works of Dessau and Katzer among others – many of whom, as Sprigge notes, “often had memories of the wartime years that presented direct conflicts with the country’s official narratives.”

Sprigge opens the book with a remembrance of her visit with the widow of composer Reiner Bredemeyer (1929-1995), who had the names of her husband’s compositions carved into his gravestone, which is situated at Pankow III along with a number of celebrated German cultural figures, singer/actor Ernst Busch (1900–1980) and conductor Kurt Sanderling (19192-2011) among them. Understanding the place of Bredemeyer, and his GDR colleagues, in the wider spectrum of the GDR’s music world is less about convenient placement of puzzle pieces that might fit current post-reunification narratives, and far more about experimentation with new ingredients in a varied stew; you may not entirely recognize the end result, but you will understand, nay appreciate, the level of creativity and labour that went into its creation. Thus is the Freudian conception of Trauerarbeit (or work of mourning) manifest in ways that move beyond simple sentimental and/or melancholy definitions, and into a more varied, thought-provoking, and nuanced take on German cultural history and its contemporary echoes, or a distinct lack thereof. How often do we hear the works of Dessau, Bredemeyer, Biermann, Dessau, Katzer, after all? With incredible attention to detail, a scholarly approach to analyses, and a clear love of the composers and their respective works across 300+ pages, Socialist Laments underlines the importance of an ever-evolving history that deserves to be – quite literally – heard and experienced. Is it a kind of advocacy? Perhaps, and perhaps that’s overdue. The book, published in mid-2021, joins a growing body of literature which looks at the work of a multifaceted era, and its people, in ways that bust out the old, Western-influenced clichés of humorless, grey grimness and show the ways in which meaning, mourning, and moving on, helped shape not only late 20th century Germany but modern Europe. It’s worth keeping in mind as the music world slowly reopens amidst coronavirus restrictions, and, to use a hoary old term, “reimagines” itself; the composers of the GDR understood this act very well, and the classical music world now, and its fans, would do well to remember such expressions and perhaps ask more from organizations, programmers, and most especially, themselves.

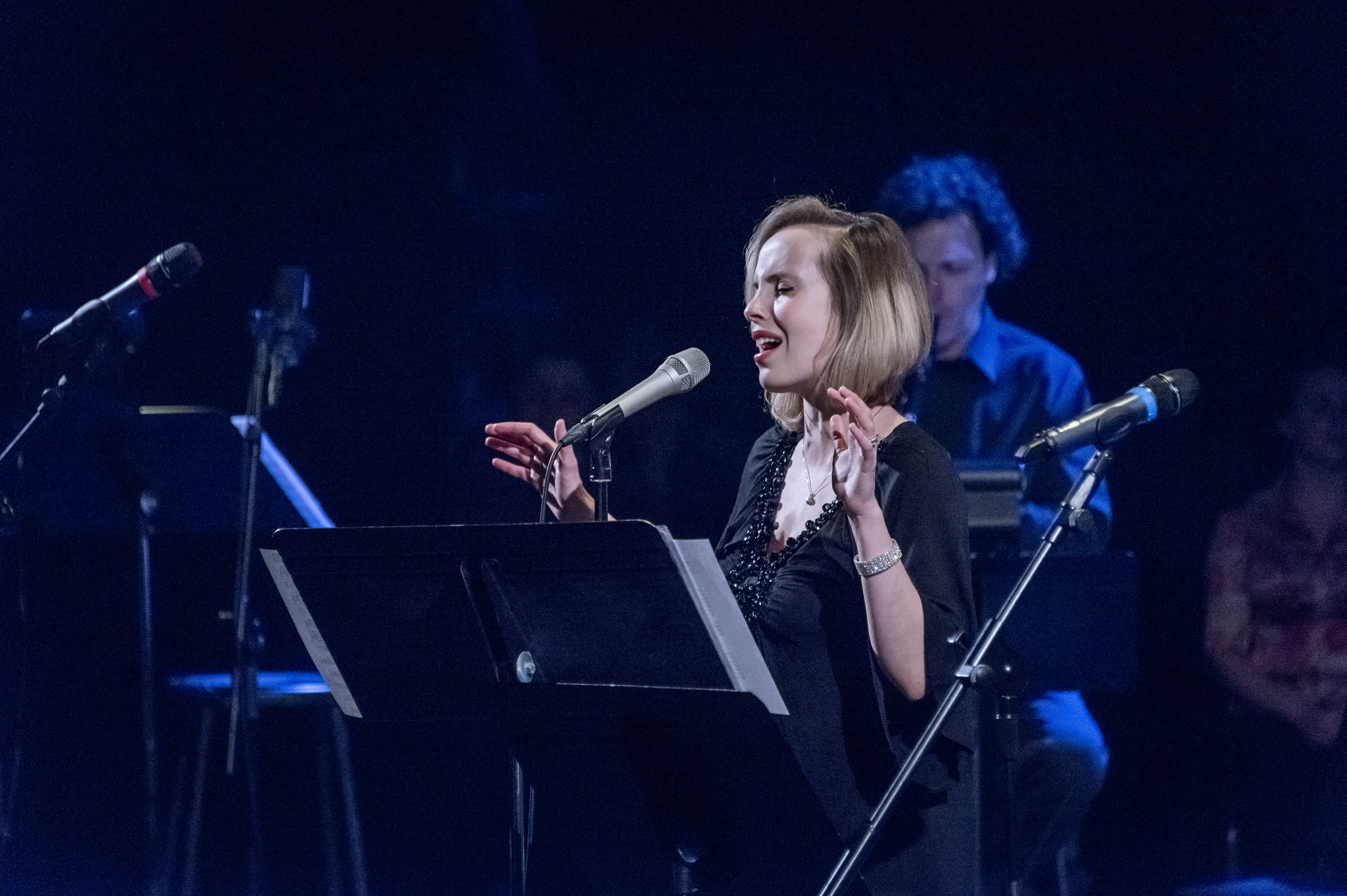

Professor Sprigge and I spoke in early July 2021.

Why did you focus on mourning and the music associated with it? You outline some academic motivations in the book but I’m curious about personal instincts.

Why did you focus on mourning and the music associated with it? You outline some academic motivations in the book but I’m curious about personal instincts.

This is a great question that I love answering! As you mention, I give a more academic explanation in the intro to the book, but there are a few more experiential reasons for choosing the lens of mourning to approach East German music culture. Musically, I’ve had a slightly morbid fascination with mourning music for a while, possibly longer than I realized. When I first started working on this project I was chatting with an old friend from high school, who reminded me of the number of requiems and choral mourning works we sang in the choir we were both in growing up – she joked that I must have really taken those experiences to heart! I suspect my personal experience of singing and playing mourning music might not be all that unique; memorial customs are everywhere in Western art music customs, though we might not always consciously be paying attention to the relationship between a generic title – for example, Requiem, Epitaph, Elegy, or a dedication, (like Schumann’s piano piece “Remembrance,” which was written the day Mendelssohn died) and the mourning rituals that lie behind them when we listen to or play these pieces. But sometimes we are (consciously paying attention), and I wanted to explore these customs and their continued use in more depth, especially in 20th century Europe, or after WWI and WWII specifically), when both the musical languages and the subjects of mourning were dramatically transformed.

In terms of the historical time period, I was struck by the disconnect I felt when I first read/heard about the GDR in (admittedly Western) texts, compared to the emotional impact that many of the sites of the former GDR had when I first visited them (and in the time since). The texts seemed to present East Germany as incredibly restrictive, especially in terms of emotional expression, while the sites I visited were sites of so many insurmountable losses, from wartime monuments to former concentration camps, that would seem to prompt an emotional response. I thought that looking at music would be a way in to exploring the various tensions surrounding expression in East Germany, not least because commemorative practices – and music – were so central to the cultural life of the GDR.

So how did this project actually begin?

Around 2005-2006, you could take a history class about the 20th century, and you’d learn all this political stuff; then you’d take a music class about the 20th century, and you’d learn about these seemingly very detached things – but I realized, in taking them in university, that they are closer together than one might’ve thought they’d be. These elements of history are not just political, or apolicial, not strictly one thing, or another; there’s messiness there. And I like messiness.

How do you go about capturing aspects of that messiness, or did you feel you had to clean some of it up yourself?

I guess, I got into this topic through the music and related places, and so in that way, it comes through in my organization of the book, it’s like, places and music are interlinked, very much. I had started from that perspective of, “This music is interesting; these places are interesting” – they reveal all these multiple histories if you sit and pay attention, or walk and pay attention – and as I read more, I realized that there was something more to that than just me liking going on walks and listening to music; there’s something one can do if one takes a very site-specific approach to an historical topic that kind of mirrors a piece-specific approach to an individual work. I broadened it out from there.

Did you intend for the introduction to feature Bredemeyer’s widow, or did the idea come later?

That was after I met her. She is such a generous woman; we sat and talked for long periods of time. I was a grad student at the time, and I mean… who does that?! Who invites you into her home and lets you converse about this time period in such a way? I’m not even German! But that level of generosity stuck with me. And as I worked through this book and thought about what to do next, it occurred to me that this is a central part of the story; these women – it’s usually women – have spent years collecting their husbands’ works and figuring out what to do with them, they’re telling these specific histories in how they archive. So yes, I remember, I left that conversation and I did not actually know about Bredemeyer’s grave until I spent that time with her, after that, I went and found the grave the next day. In the first draft of everything ,which was my dissertation, this meeting with her was at the end, but as soon as I reworked the material into a book, I thought, “This meeting needs to go at the beginning, and it can broaden out from there.”

Such generosity points to a humanity that I think is very often ignored or taken for granted in the history of the GDR in terms of how the West thinks of it…

That’s very true.

… and that notion-busting extends to gender also. I love the observation you make about how gender parity under communism was every bit as performative as elements of commemoration; I wonder if there’s a companion book to be written on that topic.

Funnily enough, that’s what I’m hoping to do next!

Psychic powers!

Yes! There’s something about it though – and, the longer you stay in this particular world, the more ideas you get to write about. I think the music… the longer I stay in this field, the more I feel there’s a lot more that can be said, not just about composers who identify as women and how they navigated it all, but the much broader set of activities that took place to make the musical world work for them, and their partners, under that system.

That’s part of the nuance which is so palpable, along with the references to the Soviet Union. How challenging was it to navigate that element? I ask this as someone who interviewed Marina Frolova-Walker, whose work you also reference in your book.

That’s a good question – funnily enough, I read your interview with Marina this morning! Well, the Russian thing… I think especially now, Shostakovich is getting programmed significantly more often than most other Russian composers, especially the next generation – I mean, nobody’s running to tell you about Edison Denisov…

Sure, but there is a common frame of reference that a lot of Western audiences and musicological audiences have, and in some ways I could rely on the fact that the audience probably already know a fair amount, or have a fair amount of ideas, about the music of the Soviet Union, so I figured, with good footnotes and recognition, I could imply the realization that, “Yes, I know you want to know about Shostakovich right now, so here you go; here’s the formal reference” – but the other, thornier question, in terms of thinking about the field of musicology, or how people thought about artistic practise in the Cold War, for far too long… it was so very Soviet Union-focused. So some of what I was doing was building on the work of other scholars who have taken this very interesting era and explored how yes, the Soviet Union was hugely influential on East Germany, but the musical life there looked, and sounded, different. And that is significant.

Photo: Eric Isaacs

How much do you think the current interest is fuelled by “ostalgie”?

Oh for sure, a good chunk of it, there’s no question. I got into this field right around the time of the 20th to 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. You’d go to these conferences (2010-2015) and there would be a certain generation of people saying, “Well I went to East Germany and it felt like this” and “I remember life was like that.” You know, this past week I came across a list of movies that were meant to help you understand the GDR but none of them were actually by East German film artists… so, I mean, people are intrigued by this era and place, because they have this idea of what East Germany was.

One that has been largely shaped by Western ideas, as you noted.

Yes, that’s right.

But the sense of nostalgia within Eastern cultural expression is also significant; the interplay between nostalgia and reality, sentimentality and authentic expression, seems especially relevant to contemporary programming. Why do you think the work of East German composers isn’t programmed more often? There was a production of Dessau’s opera Lanzelot (1969) in Erfurt and Weimar) in 2019, but that seemed unique.

I think the reasons might’ve shifted – it was always multifaceted, why they were or weren’t heard. In the 1990s, there is ample evidence to indicate that yes, Western intellectuals took over former East German institutions for reasons which were based on completely discrediting Marxist thought; for a peek into that kind of world, Anna Saunders and Debbie Pinfold have this great book (Remembering And Rethinking the GDR, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2013) demonstrating this sort of effect in various areas of the arts and culture and in universities, with some of the essays (“Reflective Nostalgia and Diasporic Memory: Composing East Germany After 1989“, Elaine Kelly) exploring the cultural atmosphere of the early 1990s in that vein. Bredemeyer himself commented on this issue as well; he said he felt like his works were being shaken off, that the perspectives this generation of composers had grown up with had suddenly been discredited. And, I think there’s this other dimension, which is more connected to new music writ large, and that is… it’s hard to get programmed. A lot of composers are continually and justifiably complaining about this or, if not complaining, aware that it is a system where only a few people get programmed again and again and again, and there is this broader movement which is not necessarily linked to the collapse of communism. Also, yes, the new music world is modelled on a world that is almost a century older now.

That makes generational divides all the more stark, and also brings up some very timely ideas around funding, especially in the post-Covid cultural landscape, or whatever we’re in now…

Which-Stage-Now-Covid…

How much did those elements – intergenerational, financial – come into play as you were researching and writing?

One of the things I realized I had to do at some point in this project, for my own sanity, and also to do justice to that messiness I referenced without making it a free-for-all, is that I had to focus on a certain generation that had come of age, or a couple of generations, that came of age during WWII and then came into the GDR as fully grown adults, versus those born during the war, and then those born in the GDR and after – I just don’t know enough about the more contemporary ones to comment. I’ve been tangentially following this third-generation group who were children when the GDR collapsed, or are first-generation and born in reunified Germany, but may well have parents from the East, and they’re adults now, doing various creative things – I just haven’t followed them as much. I think there is that dimension of how much people are holding onto stuff from the past, compared to how much those elements they think of with so much nostalgia have, in fact, morphed into totally different things. Like the element you mentioned about levels of state support – that’s also been fused into this whole idea of, ‘where do you go to get your works performed?’ – which I think is very valid right now. Europe seems to support musicians more than the U.S., for sure.

Indeed, and North Americans never get to hear the work of people like Bredemeyer or Dessau performed live as a result, because programming them is perceived as too risky. Do you think in our current pandemic era we might start to appreciate these artists, people who wrote through their own difficult times?

Possibly. I finished this book right as Covid started, which I wrote about in the intro, and I was thinking, “What on earth is going on? I have to finish this book!” So that opening chapter is colored by that whole initial experience, but throughout the book some of the examples I was working with made me think about motivation in multiple ways, and in slightly different ways – there’s this kind of potential therapeutic element of, “This is my response to this situation; this is what I do. I’m a musician: if something happens, I’m going to respond through music” – so I think it is possible that composers and audiences may turn back to, and look for, these moments of mourning in sound. There was this article at the beginning of the whole thing I saw, about music during the plague, the Renaissance, about it being repurposed and in thinking about that today, it’s possible that would happen now, but I can also imagine… I don’t know what format it would take, whether it would be a composer turning back to previous examples and pondering how that would help them work through things. Speaking for myself, I love work that changes the way I listen to and comprehend other music. To give you an example, I’m struck by Mauersberger’s turn to Schutz; at first my reaction was, “Well of course, it’s Dresden!” – I studied Schutz as an undergrad with a scholar of his work, but then I thought, “Hold on a second, Schutz and the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648); Schutz and all the religion issues” – there were lots of potential layers.

So yes, it would be really interesting and intriguing if audiences did turn back to music, maybe GDR music, and, this sounds twee, but to music that fully represents this current time of need. I can also see that taking different forms; for instance, Courtney Bryan recently had the premiere of her Requiem in Chicago, which was postponed from before this whole thing, but the work takes on a new meaning now. The form is still there, but musicians are adapting and making such works fit to the present, which seems very similar to what the composers I studied were doing.

Some may look at your askance for not being European and doing this; how much do you think being a kind of cultural outsider helped or hindered your writing and understanding?

I think there’s been so much attention and work and really rich stuff written about East Germany, and the arts in East Germany, over the past decade or so, so it’s not just one book everybody’s turning back to anymore, or one person; it’s not like, ‘if you read German then you definitely read this person; if you read English, you definitely read this person’ – no, it’s a bunch of people. There’s this rich, very engaging dialogue taking place now. So I don’t think I’d feel comfortable writing this if I wasn’t in dialogue with that larger community. We need both perspectives, from insiders and outsiders; it’s the only way to form something approaching a complete picture.