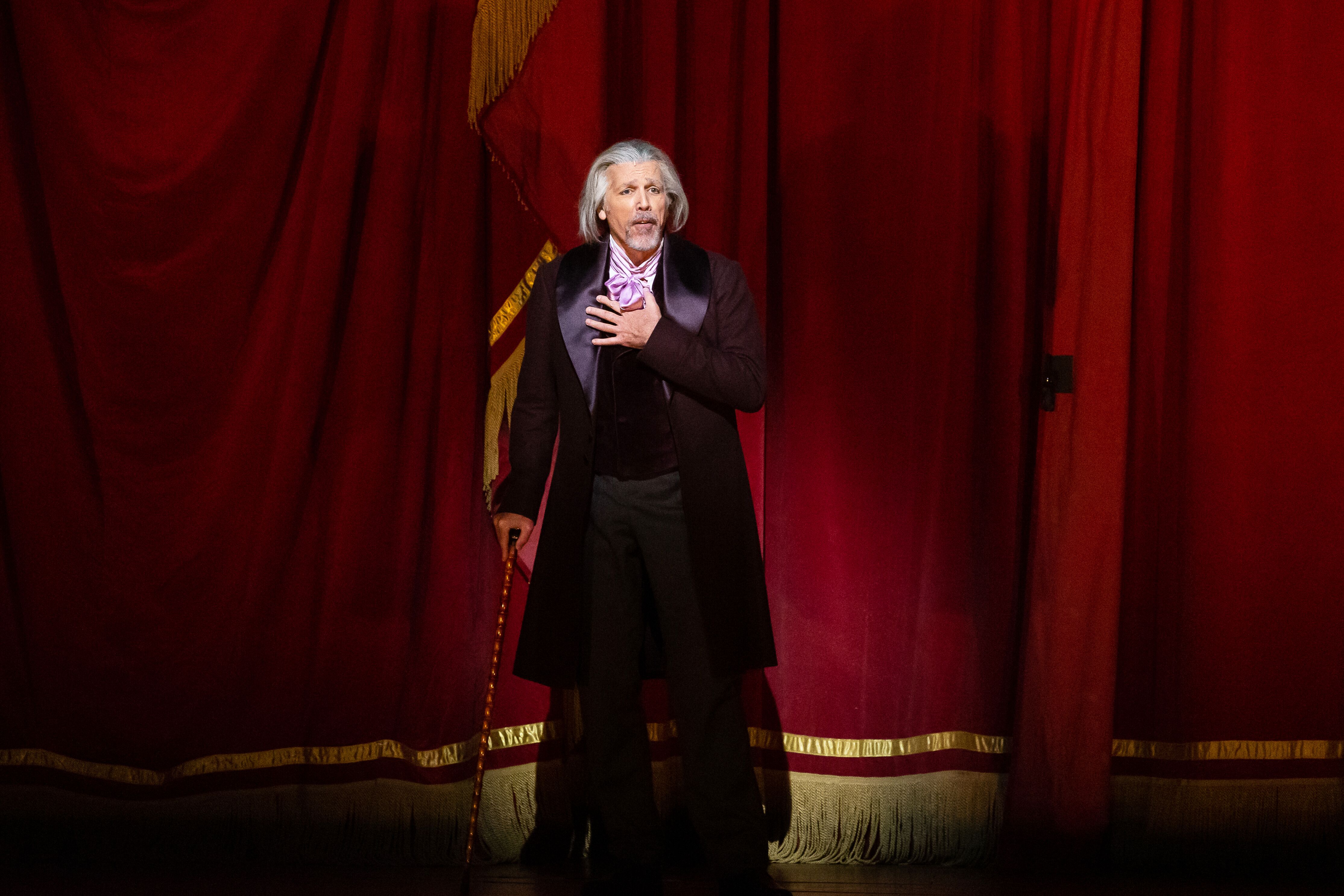

Photo: Paul Marc Mitchell

When I last spoke with soprano Chen Reiss, she was in the middle of planning a Beethoven album. At the time, she spoke excitedly about possible selections, and happily shared a few morsels of insight her research had yielded. The fruit of that study is Immortal Beloved (Onyx Classics) a delicious collection delivered with Reiss’s signature mix of lyricism and authority, accompanied with sparky gusto by the Academy Of Ancient Music and conductor Richard Egarr. Released in March, the album is the latest in Reiss’s very ambitious discography featuring the music of Mozart, Mahler, Meyerbeer, Lehar, Schubert, Donizetti, Rimsky-Korsakov, and many others besides. The title of this latest album is an intentional reference to the name Beethoven gave to a mysterious woman in his life (the identity of the “immortal beloved” has long been a source of speculation), and showcases of the breadth of complexity pulsating within Beethoven’s early writing style. Far from fantastical, flights-of-fancy lovey-dovey ditties (the composer didn’t do those), these are sounds rooted in a very earthy sensibility. Reiss’s performance of these notoriously difficult works is a heartfelt embrace of the human experience and the myriad of emotions within. What was a thoughtful listen in former, so-called normal times takes on an even more contemplative shade in the current one.

Like many in the classical industry, the usually-busy soprano has been affected by cancellations stemming from the corona virus pandemic. Just two days into rehearsals at Semperoper Dresden last month (as Morgana in a planned production of Handel’s Alcina) the production, following others in Europe, was shut down. Thankfully, Reiss did get to record a sumptuous concert with the Academy of Ancient Music and conductor Christopher Alstaedt in early March, at Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, one featuring a selection of tracks presented on Immortal Beloved, as well as orchestral pieces honouring this, the year of Beethoven’s 250th birthday. But, as with everything at present, the future is a giant question mark. Reiss’s scheduled appearances on the stage of the Wiener Staatsoper (as Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier and Marzelline in Fidelio), with the Rotterdam Philharmonic (Mahler Symphony No. 2), and at Zaryadye Hall in Moscow have been cancelled; her scheduled performances in June (at the Rudolfinum Prague with the Czech Philharmonic; as part of the Richard Strauss Festival in Garmisch with Bamberger Symphoniker; a return to Wiener Staatsoper in Falstaff) have not. It’s so difficult to say what could happen now; the fingers, toes, and figurative tines of tuning forks everywhere are being crossed throughout the classical world, for a return, if not to normal (an idea that seems to bear redefining hourly), than to something that might still allow for that magical energetic exchange between artists and audiences.

Photo: Claudia Prieler

Such an exchange is one Reiss is well-acquainted with. She has performed at numerous houses, including Teatro alla Scala, Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Bayerische Staatsoper, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Hamburg State Opera, De Nederlandse Opera Amsterdam, and, of course, at her home base in Vienna with Wiener Staatsoper, where she has appeared over many seasons. As well as opera, Reiss has made concert appearances with the Israel Philharmonic, Wiener Akademie, Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg, Akademie Für Alte Musik Berlin, Staatskapelle Berlin, Laeiszhalle Hamburg, the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Tonhalle Düsseldorf, Orchestre de Paris, Orchestre National de France, as well as with festivals like Schleswig Holstein, Lucerne, the BBC London Proms, the Enescu Festival, and the Liszt Festival Raiding. Last spring the soprano was in Belgium as part of a sweeping performance of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana with the Orchester Philharmonique Royal de Liège led by Christian Arming; not long after, she jetted off to Berlin, giving divine performances in Haydn’s Die Jahreszeiten (The Seasons) at Chorin and the Philharmonie, before embarking on a multi-city tour of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 with the Munich Philharmonic and conductor Gustavo Dudamel. Reiss also uses her considerable teaching skills in Master Classes at the Israel Vocal Arts Institute.

The notable cultivation of a wider array of repertoire over the past while reveals an artist who is firmly determined to be her own woman – on stage, in music, and through life. Such fortitude is reflected in the selections on Immortal Beloved, not easy works, in either musical or dramatic senses, but chosen, clearly, for the arc they provide for an holistic listening experience – a theatre of the mind indeed, with intuitive heart-and-head moments. The songs reveal not only Beethoven’s approach to vocal writing, but the types of texts he was attracted to (which, as you’ll see, she expands on in our chat). Many were written in the hot intensity of youth (Beethoven was mostly in his twenties), so it follows that the texts the composer set are equally dramatic, with Big Emotions and Big Feelings, instincts that only grew in shape and complexity with time. There is a definite dramatic arc to their arrangement on the album, with the Mozartian opening aria, “Fliesse,Wonnezähre, fliesse!” (“Flow, tears of joy, flow!”), taken from Cantata on the accession of Emperor Leopold II, composed in 1790. A young Beethoven was clearly wearing his influences on his sleeve here, an instinct which weaves its way throughout Immortal Beloved, where discernible threads of not only Mozart and Haydn, but contemporaries like Johann Baptist Wanhal, Fran Ignaz Beck, François-André Danican Philidor, and notably Étienne Nicolas Méhul can plainly be heard; the bricks laid by these classical composers along the path of composition – melodic development, instrumentation, counterpoint, thematic exposition – were absolutely central to Beethoven’s own creative development, and can plainly be heard on Immortal Beloved, both in the smart vocal delivery and the knowing, quiet confidence of Egarr and the Academy.

The emotionally turbulent “No, non turbarti” (“No, do not be troubled”), scena and aria for soprano & orchestra, features Reiss carefully modulating tone, stretching vowels this way and that with just enough oomph to quietly underline the vital schlau, a quality she feels is central to understanding the piece. “Prime Amore” (“First Love”), which follows, is characterized by Reiss in the liner notes, “a startlingly mature way of looking at love’s complexities” and is conveyed with piercing tonal purity and tremendous modulation. The melodic grace of Fidelio, Egmont, and the incidental music for Leonore Prohaska (for a play by Johann Friedrich Duncker about the military heroine) highlight the soprano’s elegant phrasing, easy flexibility, and sparkling aptitude for injecting drama at just the right time, with just the right phrasing and vocal coloration; even if one doesn’t understand each word within their broader tapestry, one nonetheless feels the threads of multi-hued emotion running through and between them. Delivered with controlled passion and a watchful eye for storytelling, the selection of songs clearly convey a keen sensitivity to both the complexity of the writing and the complicated histories of their creation. As the liner notes remind us, the circumstances in which these works were written (and only sometimes performed) were less than ideal, and were frequently the source of sadness and frustration for their composer.

However, not all the material on Immortal Beloved is steeped in poe-faced seriousness; “Soll ein Schuh nicht drücken” (“If a shoe is not to pinch”) is a jovial little number, performed with a wink and a definite smile in the voice. Written in 1795 and taken from the singspiel Die schöne Schusterin (The Shoemaker’s Wife) by Ignaz Umlauf (second kapellmeister to Vienna’s Hofkapelle, or Court Chapel), its jovial lyrics, reflected in the lilting music, fit within the overall playful nature of the work (the wife’s husband is named Sock, because of course), providing the album with some needed softness amidst its many sharper edges, ones which are displayed to perfect effect with the elegant ferocity of “Ah! perfido” (“Ah! Deceiver”). The famous two-scene aria, composed in 1796 and based on the work of Metastasio, has its roots in the mythological figures of Deidamia and Achilles. The song is an extended and emotionally varied lament over the antique hero’s abandonment and rejection of the narrator; it moves rapidly between fury, despair, confusion, and longing, feelings which inextricably fuse text and music. As has been noted, Beethoven’s Deidamia could be “a younger sister of (Mozart heroines) Donna Elvira, Fiordiligia or Vitella. Yet “Ah! perfido” contains elements that can act as premonitions of Beethoven’s later vocal style, where the mosaic of changing emotions is replaced by consistent and deepened psychology.” With “Ah! perfido” Reiss has chosen to close the album on a deliberately, and quite deliciously, thoughtful note. Indeed, there is something reassuring about Reiss’s sound across the whole of Immortal Beloved, one that blends strength, beauty, and wisdom, while showcasing an inherently intelligent approach to narrative and to creating a deeply satisfying listening experience, one which, in our current times, is more needed than ever.

Like many in the music world right now, the soprano has turned to the online world for sharing her talent, and for showcasing that of others. On her Instagram account, she hosts exchanges with fellow artists as part of collaborative digital project Check The Gate. One recent exchange featured cellist Gautier Capuçon, with whom she performed in Paris as part of Bastille Day celebrations in 2019; another featured director Kasper Holten. Her virtual performance with guitarist Lukasz Kuropaczewski, of Schubert’s “Frühlingsglaube” (“Faith In Spring”, with its encouraging text, “Nun, armes Herz, vergiss der Qual! Nun muss sich Alles, Alles wenden” / Now, poor heart, forget your torment! Now all must change”), is particularly stirring. Reiss has also been featured in broadcasts of productions streamed through the Wiener Staatsoper website. Most recently she can be seen as an elegant Ginevra in Handel’s Ariodante, as well as a very cheeky Bystrouška (the Vixen) in Das schlaue Füchslein (The Cunning Little Vixen) by Leoš Janáček. Here the soprano conveyed a ferociously charismatic stage presence that alternated smoothly between thoughtful notions of innocence, experience, and everything in-between. Blake’s lines that “Mercy has a human heart / Pity a human face; / And Love, the human form divine; / And Peace, the human dress” never felt more immediate than when experiencing (however virtually) her elegant intonation and lyrical vocal prowess in handling the complexities of Janáček’s delightful and truly tricky score. One positively thirsts to experience her broader explorations into the composer’s world, and fingers are crossed for things to manifest in what is currently, as for so many, an uncertain future.

More livestreams are, however guaranteed, in the interim. On May 2nd Wiener Staatsoper is set to broadcast Fidelio, which will feature Reiss as Marzelline, a role she is well familiar with, and there are sure to be more interviews and performances on her Instagram page as well. Over the course of our conversation in mid-March, just as Reiss was preparing to leave Dresden for home in Vienna, we chatted about a wide array of topics, including Immortal Beloved, as well as the impact of the cancellations, and the possible meaning Reiss is taking from the current situation.

What was the motivation to do these not-so-well-known pieces?

Actually that was just it: these pieces aren’t well-known. There isn’t any one album that has collected all these pearls for sopranos under one roof – you have to buy an entire Beethoven edition. There are so few recordings of these works, and I thought, why not? They’re so good, they should be standard repertoire, they should be recorded as often as Mozart concert arias and performed onstage. Most are early Beethoven, taken from the time he was living in Bonn and before he came to Vienna.

With “Primo Amore” for instance, for many years everybody thought it was written during his time with Salieri in Vienna; researchers found out recently, in comparing ink and paper, that it was actually written in Bonn before he came to Vienna, and to German text, and it was never published. Most of the pieces (on Immortal Beloved) were not published in his lifetime; he did revise them and had the intention of publishing them but didn’t come to do it because he was so particular and such a perfectionist. I think that he just didn’t trust himself with (writing for) the voice – it didn’t come to him as naturally or organically as writing for piano or orchestra – so (his vocal works) were just left in the drawer. Magdalena Willmann was a neighbour’s daughter in Bonn, and he was possibly in love with her, and we known he wrote (“Primo Amore”) for her. And the shoe aria (“Soll ein Schuh nicht drücken”) is an unusual piece for Beethoven; it’s a buffa aria, written a very Haydn-like style. It’s a humouristic aria, he wrote it for her also; we know that because (Willman) was soprano and had a very good lower range, and in those pieces there are a lot of passages where he’s using the lower range for an effect, either a comic effect or to express very extreme feelings. (Willman held a position as first soprano at the Bonn National Theater.) So it is very challenging because almost in every piece there are two octaves at least!

What’s that like for you as a singer? How do you approach it?

I put in ornaments – I built them in, because it’s early Beethoven and because I (recorded) it with an early music ensemble. Some of the (works) were written in 1791, 1795, around there – Haydn was still alive, Salieri was still writing, so they’re very much classical. The pitch we used to record is A=438 and not A=443 or A=442, which was used more in the Romantic time later on. It’s a very classical period (for these works) and I wanted to use ornaments, since some passages (of the songs) over two octaves. This is why I think it’s great for sopranos – you can show a very big talent of expression, of colors, of virtuosity. And with Beethoven, the virtuosity is not virtuosity for the sense of showing off the voice, but of showing big emotions: everything is bigger than life; we are pushing boundaries in every possible way, rhythmically, dynamically, harmonically. The length of the pieces is noteworthy too – “Ah! perfido” is fourteen minutes, “Primo Amore” is around fourteen minutes; no one wrote, at that time, such long songs. Mozart’s concert arias are between seven and ten minutes! Beethoven was using a bigger orchestra too. So clearly he liked to do everything big for his time.

For me it was pushing my boundaries, like “Ah! perfido”, a work which is so identified with bigger voices, like Birgit Nilsson and Montserrat Caballe and Cheryl Studer – these are big voices but I think today more and more lighter voices are singing it, and I believe this is the kind of voice that sang it in his time.

Over the last few years, that undercurrent of very dramatic, authoritative sound has been developing in your voice, though The Times described your sound as “soubrette”…

I don’t think I was ever a soubrette. I know some people say this but my voice never had this edginess, it was a light voice, a pure voice. Of course I sang roles that are soubrette-ish, like Adele (from Die Fledermaus) or Blonde (from Die Entführung aus dem Serail), but I no longer sing them – not that I can’t but I don’t find them as interesting. And I think the color of the voice… it was always an elegant voice, and in this sense I don’t know why people say it’s soubrette, I would not say it, but again, I’m very happy that they chose it as CD of the week! Everyone has a different view of voices; it’s quite individual.

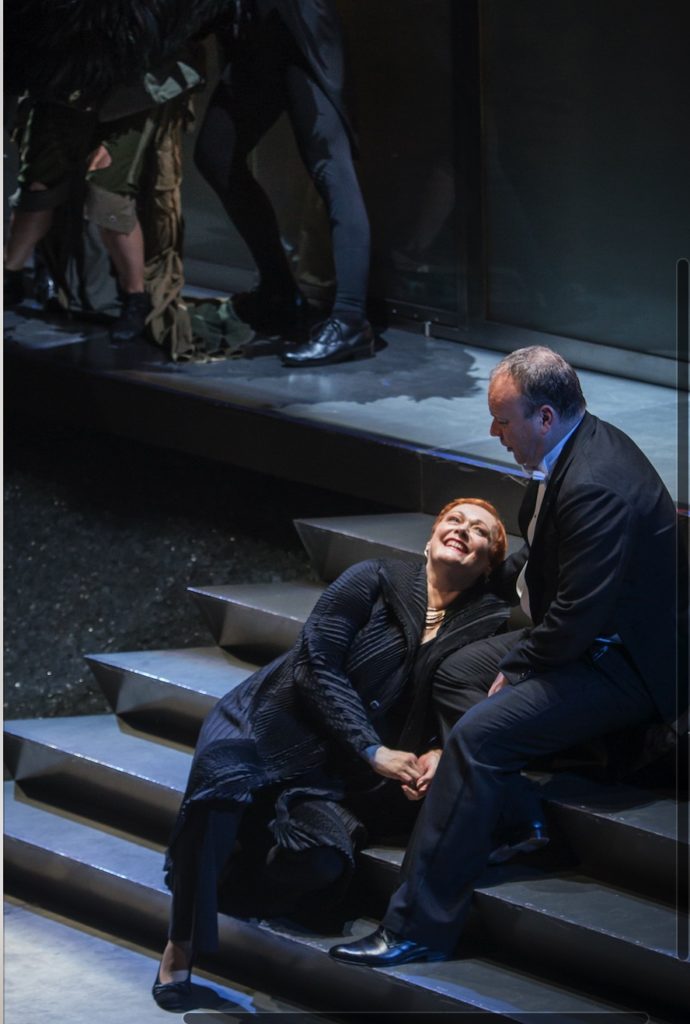

With Rene Pape in Fidelio at Wiener Staatsoper. Photo: © Michael Pöhn & Wiener Staatsoper

You’d said when we spoke before that you don’t like being slotted into one style, a view that’s been echoed by singers I’ve spoken with since, and I wonder if that is the result of a need to be flexible now in the opera world, or of wanting to be more artistically curious.

I think it’s happening because more and more singers are taking their careers into their own hands – well, “career” is the wrong word, but singers are taking charge, yes. I think we’re tired of being told all the time what to do. When you start as a young singer, yes, you have to obey everything, you have to take every job that is being thrown at you, but when you get a little bit older, there are benefits to that, one being that you can also make your own choices and you can say, “no, I actually don’t feel like singing this role anymore, I want to do something else” and also, “I want to do my own projects” – meaning, “I no longer want to be just a team player, it’s great to be that and I love doing it when I do opera, but I also want to do my own projects where I am choosing the repertoire, where I am choosing the partners I will work with, where I choose what will written in the booklet and what will be the order of the pieces and what will be the title of the CD.” So basically, I think that it’s coming because we singers feel a need to be more, not more in control, but we want to have more responsibility over our artistic choices. And we want to present a complete product from beginning to end where we can say: this is me, this is mine, this is what I want to share with the world.

And this is why I took this (Beethoven) project. It was huge – it took me two years to realize it, to come up with the idea, the research, learning the pieces, learning the circumstances in which the pieces were written, finding the titles, choosing the photos, writing the booklet – it took a lot of time. I’m very proud of it and very, very happy because I feel that every tone that comes out of my mouth on the CD is 100% me, and no one is telling me how to sing and how to present myself, which is often the case when you do opera – they tell you everything: they choose your clothes, they choose your hairstyle, they tell you what to do on stage; how to move, how to breathe, how the lighting will be, the conductor is dictating the tempo whether it’s comfortable or not – usually you can’t say anything about it – the orchestra is playing as loud as they want to so… you’re kind of left out there … when you really have very little control of the end result, but when you do a CD and you are the soloist, you have much more control of the end result.

Some do albums because they want a broader appeal, but the songs on this album are musically complex – how were they to prepare?

They required a lot of practise and stamina – they’re long, and written… not in the most singable way, I would say. Some of them are very instrumental, some of the coloratura was composed, not for the voice but as if he wrote for violin – there are all kinds of weird intervals and sequences, and the voice doesn’t want to go there. Also dramatically they are not easy; to keep the tension, one has to have a very clear plan dramatically and vocally. “Ah! perfido” is the exception – that is an exceptionally well-written scene, dramatically and vocally, but it’s one that came later. Others, like “Primo Amore”… it is so difficult to make sense of the character, it’s like a big salad, Beethoven is throwing in every possible compositional idea that he had in there, and in certain ways, in terms of form, it’s not the best written aria! So to make sense of it was not easy. Some of these works just require you to spend more time with them – they’re not as organic as say, Lucia’s mad scene, which is pure bel canto. But I think they are very interesting!

The text is so interesting, as are the characters – strong women, independent women, women with ideals of a different world, women who want to change the world, to take charge, to take things to their hands – these are the kind women he admired, and this I why I called the album Immortal Beloved; we don’t know who she really was… maybe an ideal in his mind.

In the booklet you contrast Mozart’s female characters with Beethoven’s, which is such a smart way to contextualize the world in which Beethoven was living and writing; he would’ve known all these Mozart heroines but he went for something entirely different.

Yes, I think he appreciated Mozart very much musically but I think he was much more advanced in the ideas of the world and society as related in that specific sense, but for me, Mozart is beyond a composer, it’s musica assoluta, it’s really… the truth, like, God has spoken! It’s music itself; there can’t be anything better than that. But it’s something not human, and Beethoven is very human – he’s perhaps the most human composer. It’s wear-your-heart-on-your-sleeve music in the most direct way, although not at all in a Puccini way!

What was your experience of working with the Academy of Ancient Music?

I was debating whether I should use a Viennese orchestra, and I knew I wanted an original-instrument one. The English period instruments are really so fabulous, so quick, they have a great tradition, and in recording you need people who are really “on” there. I was doing the Egmont concerts with them last summer, so I thought, why not extend it and do the whole CD with them? Egmont was the starting point, the catalyst, and the performances were around the time I wanted to record, so it just made sense. I’m very happy we did it; they sound fabulous and I really enjoyed working with Richard, his energy is wonderful.

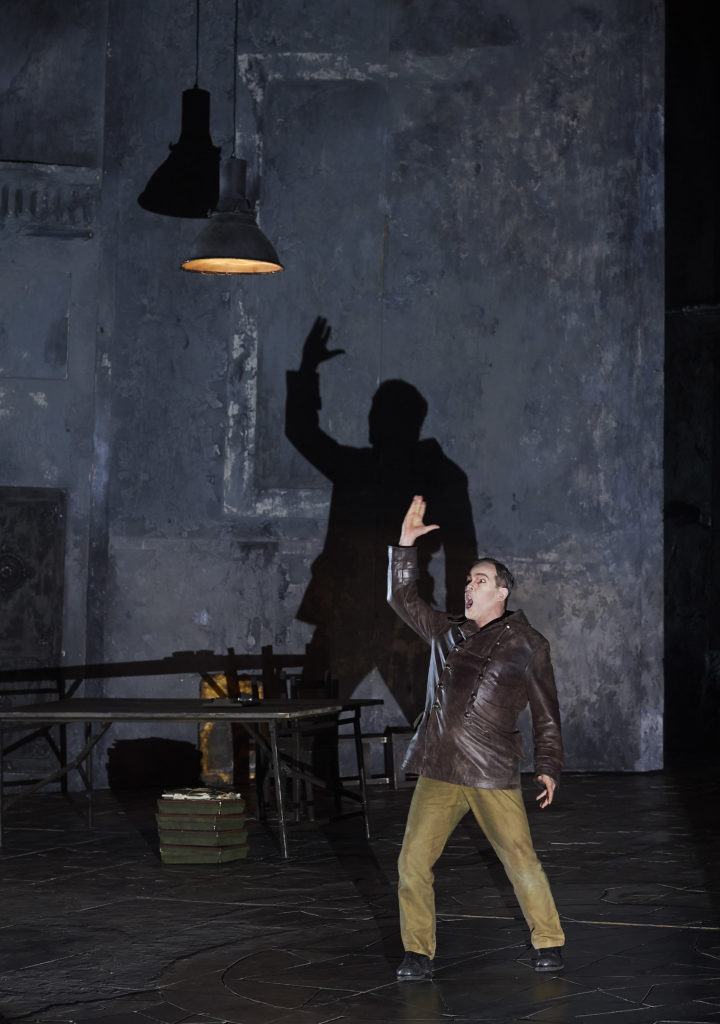

As Marzelline in Fidelio at Wiener Staatsoper. Photo: © Michael Pöhn & Wiener Staatsoper

Your vocal work has become more varied over the last two years or so. I wonder if making this album has made you approach other work differently.

Marzelline as a character is really difficult – there is a lot of text in a very uncomfortable zone of the voice; it’s parking her in the passaggio, with lots of text. I’m trying to sing her as round and delicate as I can. Strauss is a completely different story! He’s a composer I think is so wonderful for sopranos, and I’m so happy to sing Sophie (from Der Rosenkavalier) because it’s so comfortable in the voice. I love singing Zdenka (from Arabella) too – it’s more challenging rhythmically and very chromatic, so one has to be more careful and really look at the conductor, otherwise you lose it! Sophie is a more fun role but Zdenka is a very interesting character.

In Beethoven, I like singing some things. I love “Ah! perfido” – it’s a great piece. It sits so well in my voice, especially in terms of the range – surprisingly. This was the piece I was most afraid of, but it just feels very good! I love singing the shoe aria too – I think it’s fabulous and so funny and really well-written. And I really love the aria with the harp (“Es blüht eine Blume im Garten mein” /”In my garden blooms a flower”, from Leonore Prohaska). I think it’s a jewel…

It’s a favourite of mine too, although it really goes against what many think Beethoven “sounds” like…

Yes! It reminds me so very much of Schubert; you can hear him going off in that (musical) direction throughout this one. I also like “No, non turbarti” because of the text. It’s an aria of deception: (the narrator) has deceived (the female subject), and in such a masterful way… he’s really a master of deception, and it’s very interesting to see how Beethoven fits the music and the text so perfectly. Every sentence has two parts, the parts when he’s carrying her, and the parts when he’s calming her down. He’s schlau, as we say in German, very cunning… there is no storm coming at all! He’s talking about the storm inside him, the storm of his soul, not about a real storm, but a storm of emotions, and she’s not in real-life danger – the only danger for her is him! Then in the continuation –”Ma tu tremi, o mio tesoro!” (“But you tremble, oh my treasure!”) – he tells her, “I’ll be here at your side, I’ll save you, and when the storm is over you will go away, you will abandon me, you ungrateful woman!”

So this narrator is a bit of a drama king, then?

Oh yes… but (the words of the songs) are like a strange prophecy in terms of Beethoven’s misfortunes in love. It’s amazing that even at such a young age he was attracted to those types of texts.

In youth, every emotion is writ large, whether joy or sadness.

That’s true.

Speaking of the latter, you were going to do Morgana… ?

I’ve worked on it, yes – I learned it, though I sang it before, four years ago. So I approached it like new now – I wrote new ornaments – but we stopped rehearsal in Dresden. We rehearsed two days, with two rehearsals, and tomorrow, I’m going home.

You know, this whole virus… it makes you put things in proportion. I don’t know where the future is going, even now. The fact I’m unemployed for this month and I don’t know next month… if they’ll open the (Wiener Staatsoper) house, who knows? Thinking about the future of our profession… public finding has to go to the hospitals… it just shows the priorities, of where things go, so what’s the situation with us, the freelance artists? I’m sure orchestras in the UK are worried about that as well; a lot of the players are freelance, and it means that if concerts are cancelled, they’re not being paid.

Photo: Paul Marc Mitchell

Do you feel there Is there might be any value – as you say, you learned the role, you did the prep – is there some good you still might take away from the experience?

Every time I learn a role or re-learn a role I have new ideas, new insights, and then in the future I share it with my students. But yes, you always learn about the voice, about different styles and different approaches to a role. You never know, maybe I can jump in again (to Alcina). The prep is never for nothing, it’s just… you kind of feel that it’s not complete. You have not completed the process; you complete it only when you go onstage and share it with the public.

But I think maybe this virus is there to teach us a lot of things; maybe it’s not bad to just stop. Everything just stops for a few weeks… everybody is thinking, everybody will reinvent themselves, hopefully. The one thing I’m happy about is that it’s really good for our planet; there are no airplanes flying, the factories in China were closed so the air above China is much cleaner. So maybe it’s a way for our planet to refresh itself and maybe we need to use this time wisely. Spring is a time of rebirth, so maybe we all need to clean our closets and throw out the rubbish that we don’t need and concentrate on the important things – to understand the whole world is one community and we are a small village and we need to stick together, to help each other.

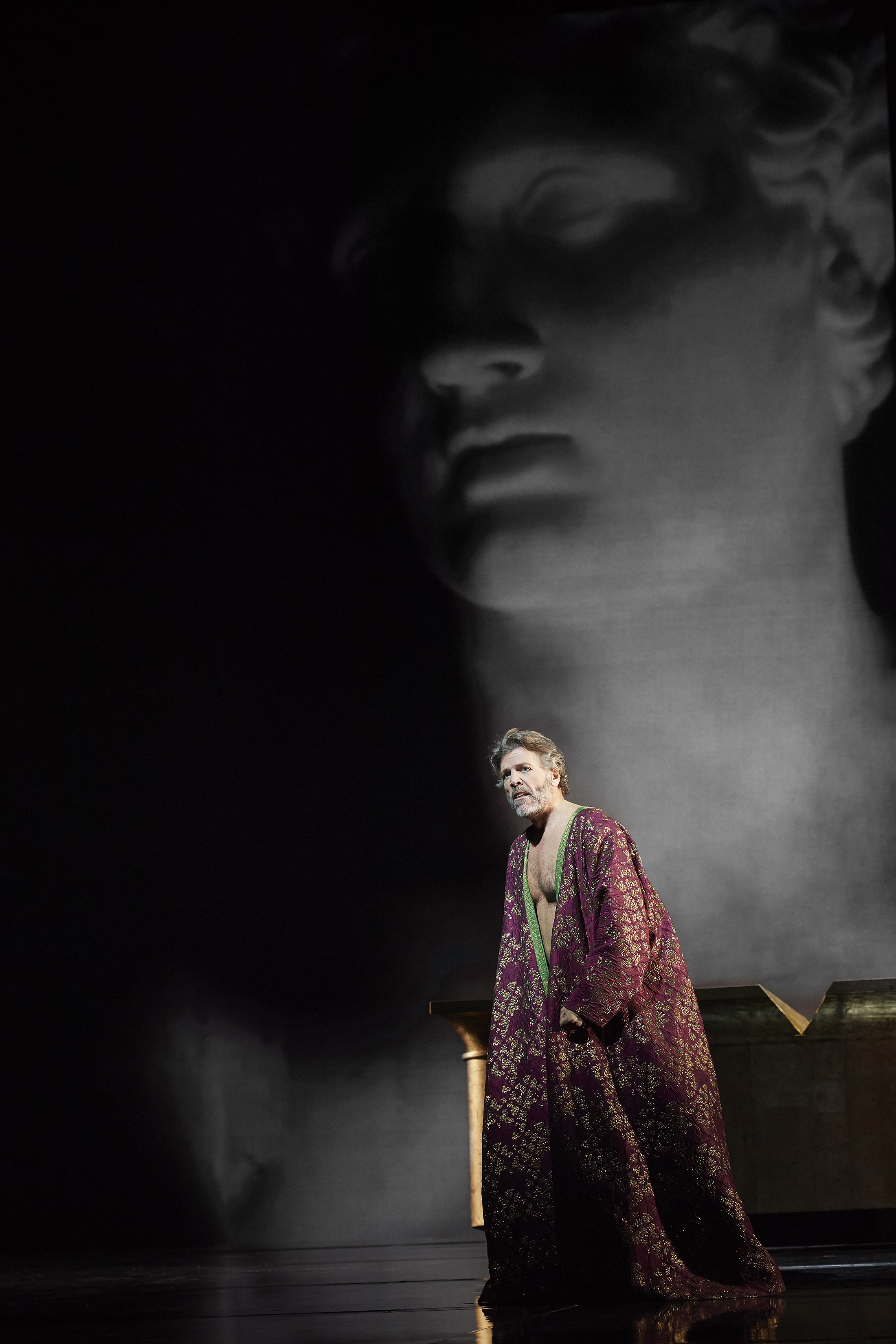

Ariodante at Wiener Staatsoper. Photo © Michael Pöhn & Wiener Staatsoper

Look, I’m very sad the performances are cancelled – I was very stressed this week. The worst thing for me is the unknown; you make plans, and what gives me confidence is that I know exactly where I am at on any given day for the next two years, and I know who takes care of my kids and… there’s a plan for everything. And suddenly, the whole plan falls apart. I don’t know where I am, the kids are not in school, my mother is stuck in quarantine in Israel. You come back to the basics and you see what is really important: we are healthy, we are together as a family, we have food, we have music – and thank God we can share it. I can share the CD with my friends, with all my fans, with social media. Even with all the bad things about social media in these times, it’s giving us a feeling of being together. And, I really hope this Beethoven album will give hope, comfort, and joy to people now that they cannot hear live music.