Most people know Opéra Comique in connection with Carmen, but there’s so much more to the famed Paris house than Bizet’s famous opera. Conductor and General Director Louis Langrée is clearly in love with the “jewel of a theatre” that has hosted premieres by a who’s-who of French classical greats, including Debussy, Delibes, Massenet, Méhul, Offenbach, Poulenc, Lalo, Meyerbeer, Halévy, and Thomas, as well as Italian Gaetano Donizetti; the theatre also hosted the French premiere of Puccini’s Tosca in 1903.

Appointed director of the Opéra Comique in November 2021 by President Emmanuel Macron, Langrée came with ideas – lots of them – though it’s clear he also possesses a wider awareness of the practicalities required to bring them to fruition. Langrée’s name is known on both sides of the Atlantic thanks to his work in New York and Cincinnati as well as his native France. Beginning his studies at Strasbourg Conservatory, Langrée went on to becoming vocal coach and assistant at the Opéra National de Lyon in the mid 1980s. From there he worked as assistant conductor at Aix-en-Provence Festival and music director with Glyndebourne Touring Opera. He made his North American debut at the Spoleto Festival in 1991. But it was his time in New York that so many North Americans may know him for, as Music Director of the Mostly Mozart Festival at Lincoln Centre, a position he began in 2003 and would hold for the next two decades. In 2011 led the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra (CSO) for the first time in a guest capacity; he became its Music Director in 2013. He’ll be concluding his time there at the end of this season.

An award-winning discography comes naturally with so many varied experiences. It includes work with the Camerata Salzburg, l’Orchestre de l’Opéra de Lyon, Orchestre Philharmonique de Liège, and Baroque ensemble Le Concert d’Astrée, covering an array of composers (Liszt, Franck, Chausson, Ravel, Schulhoff, Mozart, Weber, Rossini). In Cincinnati Langrée has recorded commissions by Sebastian Currier, Thierry Escaich, and Zhou Tian. The 2020 recording Transatlantic (Fanfare Cincinnati) with the CSO illustrates what could be an artistic ethos for the conductor in its intelligent transcending of borders and strict definitions. Langrée’s third album with the orchestra features shimmering, gorgeously vibrant readings of Stravinsky’s Symphony in C (1938-1940), the original 1922 version of Varèse’s Amériques, and the world premiere recording of original unabridged version of Gershwin’s An American in Paris. Music writer Jari Kallio wrote at its release that “Be it the ravishing colours, the ever-enchanting melodies or those uplifting rhythms, these performances of American in Paris are nothing short of an epiphany” and called the Grammy-nominated album “one of the most important releases of the year.” Yet opera isn’t a side-job for Langrée, but close to a raison d’être; the conductor has been involved in numerous opera productions across Europe – at the Wiener Staatsoper, Teatro Alla Scala (Milan), Royal Opera House Covent Garden, the Opéra national de Paris, as well as the Glyndebourne and Aix, and The Metropolitan Opera in New York, where he has led stagings of Iphigenia in Tauris, Dialogues of the Carmelites, Carmen and Hamlet, one of his favorite works.

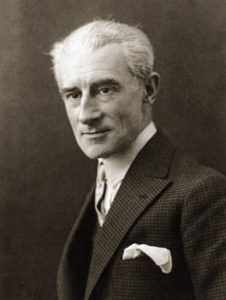

Notably open about the siloed nature of conducting and the classical world in general, the Alsatian artist made it clear in a recent conversation that his administrative demands have actually strengthened his artistic output. Notes, phrasing, orchestration – any conductor can talk about those things; Langrée is just as interested in pondering resources, labour costs, world realities. The role of education is just as paramount, and the conductor is keen to strengthen and expand the connection between artistic institutions and learning for young people who may have only cliched ideas about the opera. Offering tantalizing morsels relating to a new work (an intriguing-sounding multilingual commission), Langrée enthused on his more immediate project, the upcoming double-bill of Ravel’s L’Heure Espagnole and Stravinsky’s Pulcinella, which opens at Opéra Comique on March 9th.

The pairing feels like a highly symbolic choice for an artist who seems perfectly at ease with his audience, whether near or far. We began by discussing why he chose these works, and what French actor/director/writer Guillaume Gallienne brings to the stage of the Opéra Comique.

Why pair L’Heure Espagnole and Pulcinella as one programme?

There’s an amazing repertoire of works which were commissioned and premiered by the Opéra Comique, of course the most famous is Carmen, but there’s also Pelléas et Melisande (1902), La voix humaine (1959), Les Mamelles de Tirésias (1947), Les Contes d’Hoffmann (1881), La damnation de Faust (1846), Manon (1884), Cendrillon (1899), Lakmé (1883), all of them were premiered here, along with L’Heure Espagnole (1911). Pulcinella was not premiered at Opéra Comique and it isn’t an opera but a ballet. L’Heure Espagnole is short, it’s one-act opera, or as Ravel said, a comédie-musicale; at the time it was premiered, it was paired with Thérèse from Massenet, which is a very moral story in which a lady abandons her lover to go to the guillotine with her husband. It could have been possible to show the contrast between the two pieces, but generally L’Heure Espagnole is presented with Ravel’s other operatic work, L’enfant et les sortilèges. They are two lyrical pieces that Ravel wrote but they have nothing to do with each other.

So I wondered, what could we present? I thought of an evening with contrasting subjects and arts; when you come to the foyer of the house here, you see les quartiers allégories (the four allegories) de Opéra Comique: la comédie, le chant, la musique, et le ballet (play-acting, singing, music, ballet). I thought it would be interesting to juxtapose ballet and opera. But which subjects? With these two works we have two contrasting subjects: Pulcinella is this man who is so attractive, an irresistible sex symbol for women, and the woman in L’Heure Espagnole can’t be satisfied by any of her men.

What’s the connection in terms of musical language?

It’s a case of contrasts. Stravinsky said he had an epiphany in discovering the music of Pergolesi, it was a way for him to go further; with Ravel, we have the sound of his beginning with L’Heure Espagnole. It is just amazing, these sounds that mix music and effects: a metronome, the sound of a rooster crowing, the soldier, with sounds that are very militaristic. The orchestration Stravinsky uses in Pulcinella, however, is like black-and-white: there is no clarinet, for instance, or any kind of a sound that might give some shimmering effect. It’s oboes, horns, trumpets, trombones, this concerto grosso-type orchestration with soloists and the tutti, whereas L’Heure Espagnole is much closer to The Nightingale or The Firebird in terms of its orchestration.

Does this reflect the connection between composers?

Ravel and Stravinsky were friends – they met at the premiere of The Firebird. Diaghilev had asked them to orchestrate bits of Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina. They were using “vous” and not “tu”, but then they began letter-writing, and would open with “mon vieux” or ‘you old guy’ – it was a term of affection. (Conductor) Manuel Rosenthal told this story that on the day Ravel died (December 28, 1937) Rosenthal was conducting L’Enfant Sortileges; at the end of the evening he saw Stravinsky looking really upset, because he had lost his friend. Stravinsky went to Ravel’s funeral along with Poulenc and Milhaud – there were not many people, but Stravinsky was there.

How did Guillaume Gallienne become part of this project?

Guillaume is an immense French actor, stage director, and film director. I don’t know if you saw his film, Les Garçons et Guillaume, à table – it was so successful in France and rightly so. He has his own language, his own world, and he knows how to transmit it. He’s also gifted in how he inspires singers. The characters in both pieces here are not romantic, but they do want to be loved. Even the muscle-man in L’Heure – one is touched by his naivete. You need to accept them for what they are. It’s very difficult for singers with these works because normally they want to interpret a personage, to incarnate a person as a person, but there is none of that here, otherwise it would become a cheap piece. It’s amazing to see how Guillaume works, with his precision. Funny, because Stravinsky called Ravel “l’horloger suisse” (the Swiss watchmaker) there is this perfection in the details, as Ravel was fascinated by mechanical objects. With his opera, you don’t need to incarnate a person, you just have to sing and allow yourself to be placed in situations which are nonsense, a nonsense that makes you laugh, cry, smile, think, feel – that’s something special. Guillaume understands this perfectly. Every rehearsal with him is a masterclass.

What’s it like to return to Paris and lead a theatre so rich in cultural history?

I have a double life, the life of a conductor and life of a General Manager. When you’re in the pit, you don’t think, “My God, this place!” or “So much history!” but rather, “I should not take this phrase too fast” or “I should help the singer move on here.” You’re with very practical things. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, then you’re not doing your job.

What kind of responsibility do you feel to that history in terms of programming?

I do feel the DNA of this theatre, and everything that comes with presenting both new productions as well as works that everybody knows. You can have traditional houses, or houses where there is innovation, experimentation, trying to find new ways to do things, and generally the two are opposed, but actually the tradition of the Opéra Comique – our history – is to create, to innovate, to experiment. So even with old pieces like Pulcinella and L’Heure, juxtaposing an opera, comédie-musicale, and a ballet is a very unusual thing, but it is also symbolic of my mission. And of course we are going to continue to premiere new pieces, to give world premieres, to give Paris premieres also. But it’s one thing to create and to do the world premiere, and another to be confronted with different audiences, and have the work be interpreted by different singers, directors, conductors, orchestras.

Where do you see Opéra Comique being part of the ecosystem in the post-pandemic landscape then?

Today in the new economic situation we must have corporate users, which means that when you present a piece, either a new production or a new work, you have to find partners. For instance, after Paris L’Heure/Pulcinella is going to Dijon. When L’Autre Voyage opened here earlier this year, there were several festivals and opera managers and house directors who came to see it, and of course we hope that the piece will be presented in different places. We have also commissioned works with various outlets in Germany – and those commissions take into account traditions the Opéra Comique have always embraced in terms of languages. Gluck composed Orfeo ed Euridice in an Italian version (1762) and a French version (1774); Cherubini’s Medée had multiple translations from the French into German and Italian. So we are planning to do a new work with Matthias Pintscher now, in both German and French.

Also, and this is quite important, and maybe the main reason I wanted to come and lead the Opéra Comique, is the production and the transmission sides. We have the Maîtrise Populaire, which involves young people from 8 to 25 years old, they have part of a scholarship, morning is general studies and afternoon is for dance, singing, staging, acting. Many of these kids come from places in the suburbs of Paris where there is absolutely no contact with opera at all. Their dream might only be to become a soccer star, not an opera singer or any kind of an artist, and through this program they discover a new world – and it changes their lives. They learn that when you sing together, you must have concentration and discipline; you have to know that your partner counts on you and you can count on them, and that’s something wonderful. We are a theatre nationale, de la republique, so this is all part of our message: liberté, égalité, fraternité.

Where does this mandate toward education and development fit within your greater vision?

I arrived at an age where I feel that I must transit, I must help the new generation, I must pass the baton, and develop the image and the identity of this house and its public perception. This title, “opéra comique”, what does the “comique” part mean? People think it means operetta, but no, it’s from the same etymology as “comédie” or speaking; in opera you sing, in comedy you speak. It’s much clearer in German: “singspiel”. Opera, as an art form in the old sense, was a representation of royal power, onstage; at Opéra Comique it is the opposite, it’s the representation of ourselves as ourselves…

“Volksoper”…

Genau! That’s why The Magic Flute is a singspiel, it’s an opéra comique! And Carmen is not a princess, Manon is not a princess, Melisande – well, we don’t really know…

Your quote to the New York Times last year comes to mind:“When you have to read these Excel things and have to balance budgets and work with subsidies from the government — now, I feel like I’ve been plunged into real life. And that’s hard” – but from what you’ve said it seems as if these real-life details have made you a better artist.

Absolutely. I realize now as a conductor I was really in a silo. I used to feel an opera was the score, the dream of the composer together with voices and visuals – but now that I’m the General Manager of the house, there are so many things to think about: props, stagehands, electricians, costume designers, seamstresses. You have a larger view of the entire thing. And that awareness makes you think differently.

To what extent does that translate to your audiences?

What matters now is to understand the importance and role of philanthropy and sponsorship in relation to audiences – something I learned in the US – which is developing in its own way very quickly here in France and all of Europe. It’s especially relevant with inflation and the raising of electricity rates, in building sets and understanding raised wood prices because of the war in Ukraine. You can’t ignore all of that. And of course being on a constant budget, when you have inflation, you’re hyper-aware of salaries too. So what is reduced is the production budget, which is quite difficult, therefore we need to continue searching in terms of partners, corporate users, sponsors, philanthropists, and doing so with a lot of determination and energy.

So that’s where creativity comes in?

Entirely. I mean, a set that costs ten times more will not necessarily be ten times better. The realities force us to be imaginative. In terms of programming, there are at least three other houses in Paris – Châtelet, Champs-Elysées, Opéra national de Paris – and it wouldn’t make sense if we presented Tosca here, even though that opera did premiere in France at the Opéra Comique, and that’s only because the General Director at the time was a friend of Puccini’s. But when we present Carmen here, for instance, we present it with the dialogues, not the recits. We’ll do the same for various presentations next season. That way we don’t compete with other houses. Also a small theatre is a great advantage; there’s an intimacy here, you can whisper and have it be heard, it gives a different relationship to the stage and the music. I remember conducting Hamlet (in 2o22) and (soprano) Sabine Devieilhe was whispering during parts of the mad aria – you could hear every word. It was incredible.

Is it right to say that intimacy is part of the Opéra Comique brand?

Yes, this place is a hidden gem. My office here, the office of the General Director, is close to everything. It’s often the case that the offices of house directors are on top floors, with beautiful and impressive view of their cities, but here, I have people above me, below me, next to me, and if I leave my office… <carries laptop> in three seconds, I am on stage…. voila! <shows auditorium on camera> This proximity really says everything.