As opera companies look to attract new audiences and cultivate relationships with existing patrons, specific combinations of knowledge, passion, and energy are increasingly required. There’s work to be done with nitty-gritty issues like funding, management, casting, commissioning, programming, and presenting. Companies have made conspicuous efforts to expand the definition of the widely-understood canon of classical music. Opera watchers (including yours truly) live in hope that such decisions are more than mere gestures, that they are made with an eye toward evolution, not just optics. More than ever, works are being programmed which have been penned by composers off the well-beaten path of Opera Hits – composers who were often persecuted because of race, gender, religion, sexuality and who remain largely unknown because of a stubborn adherence to that path. Broadcaster Kate Molleson wrote a whole book about this, and I have written about it as well.

So where does the idea of “democracy” fit within the world of classical music, particularly opera? What role does (or can) art play in cultivating the idea – and the reality – of democracy? How do the notions of representation, choice, voice, equity and equality relate to opera’s history, goals, old audiences, intended audiences, financial demands, and day-to-day realities? The current Thomas Mann House series Opera & Democracy has been exploring these questions over the past six months. Instigated by musicologist and 2023 Thomas Mann Fellow Kai Hinrich Müller, Opera & Democracy is a unique combination of academic investigation, discussion, and live performance, with topics including power dynamics, representation, programming and casting choices, updated formats, and what the Villa Aurora-Thomas Mann House website calls “audience expectations as well as to academic challenges and opera’s ability to amplify the voices of silenced or persecuted artists.”

So far those artists have indeed included many persecuted figures: Gideon Klein, Viktor Ullmann, Rachel Danziger van Embden and Amélie Nikisch, Rosy Geiger-Kullmann, Ernst Toch, Tania León, and Ursula Mamlok, to name a few. Launched in Los Angeles in January, the series has gone on to see packed houses in Munich, Cologne, New York, and Dresden. More dates are set to follow in Providence (RI), Berlin, and Hamburg; most immediately is an upcoming online event June 11th with Black Opera Research Network featuring composer Philip Miller, the composer of Nkoli: The Vogue-Opera (detailing the life of anti-apartheid gay rights activist Simon Nkoli) and its musical director, Tshegofatso Moeng. Allison Smith, Civic Engagement Coordinator of Virginia Opera will also be joining the discussion together with Müller. In a recent blog entry reflecting on the New York City-based events for Opera & Democracy this past April, the musicologist wrote that “(b)y shining a spotlight on the works of composers who were once silenced by dictatorship, the week offered a way to reclaim their voices and honor their contributions to the cultural tapestry of humanity.”

Kai Hinrich Müller

That tapestry is one Müller has sought to explore in various facets. Having studied Musicology, Business Administration and Law at the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Bonn, Müller has worked as an advisor and curator on a number of international research and cultural projects, including an exhibition at Berlin’s Deutsches Historisches Museum called “Richard Wagner and the Nationalization of Feeling” in 2022. He has also also worked with musico-historical group Musica non grata and led its Terezín Summer School, the 2023 iteration of which featured Rachel Danziger van Ambden’s Die Dorfkomtesse (The Village Countess), subsequently presented as part of Opera & Democracy’s presentation in Dresden. Müller’s publications explore musical life in the interwar and Nazi periods, past and present musical structures, and the functions of music within social discourse, topics which are also long-term research focuses. In addition to his teaching work at the Cologne University of Music and Dance (since 2017), Müller also works with the Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, German public broadcaster WDR (Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln) and various concert and opera houses. As Director of the Bauhaus Music Weekend, he told RBB’s Hans Ackermann:

Meine Projekte sind immer an der Nahtstelle von Wissenschaft und Praxis angesiedelt. Schön finde ich, wenn man die Forschung “in den Klang” bringt. Musikwissenschaft soll nicht trocken sein, sondern wieder zum Klang werden. / My projects are always located at the interface between science and practice. I like it when you bring research “into sound”. Musicology shouldn’t be dry, it should become sound again.

(“Die Musik war fest im Alltag am Bauhaus eingebunden“, RBB24, 9 September 2023)

Opera & Democracy is anything but dry. Along with being an important forum for timely conversation and interaction, it is a refreshingly intelligent expression of creative advocacy, coming at a time when many (including those holding the purse strings) are questioning the role of culture within contemporary life. What can (or should) art’s role be in shaping the future? Over the course of our nearly hour-long exchange, the musicologist offered a few ideas, a real willingness to listen, and an interest in engaging with different experiences and ideas. Mehr davon, bitte…

The Goethe Institut New York hosted the opening event of the week-long New York section of Opera & Democracy. Photo: Jamie Isaacs

Where and how did the idea for a series about opera and democracy originate? Relatedly: why this series, now?

The idea came out of my fellowship at the Thomas Mann House. The theme for the 2023 season of the Thomas Mann House programme was the political mandate of the arts, examining the question of the arts having a kind of political mandate, and what that means in a broader sense. I’m a musicologist; my habilitation was on Richard Wagner and Richard Wagner’s afterlife, a bit like Alex Ross in his last book, Wagnerism, so it was totally clear for me when I got to the Thomas Mann House that I would focus on opera.

Also there is one very important centenary in 2024, and it’s related to the Krolloper, which was this very important opera house in Berlin that hosted a lot of avant-garde works. But then it became the Nazi assembly hall of the Reichstag between 1933 and 1942. So on the one hand it’s a very important place for European history, and on the other it’s a very important place for international opera history; this was such a great coincidence that I wanted to use the centenary to think about the place of opera in society and politics, especially since the United States and the EU both have very big elections this year, and Germany is struggling with the rise of right-wing parties. In organizing the series I was in touch with many colleagues in the US and Germany – directors, singers, musicologists – and initially they all said, “Hey Kai, are you joking? ‘Opera and democracy’, this is a kind of contradiction!” – sure, but sometimes the tension is much more interesting with such pursuits. So we started, and so far it’s a real success for the Thomas Mann House and the broader academic world.

How did you choose the lineup of guests and events?

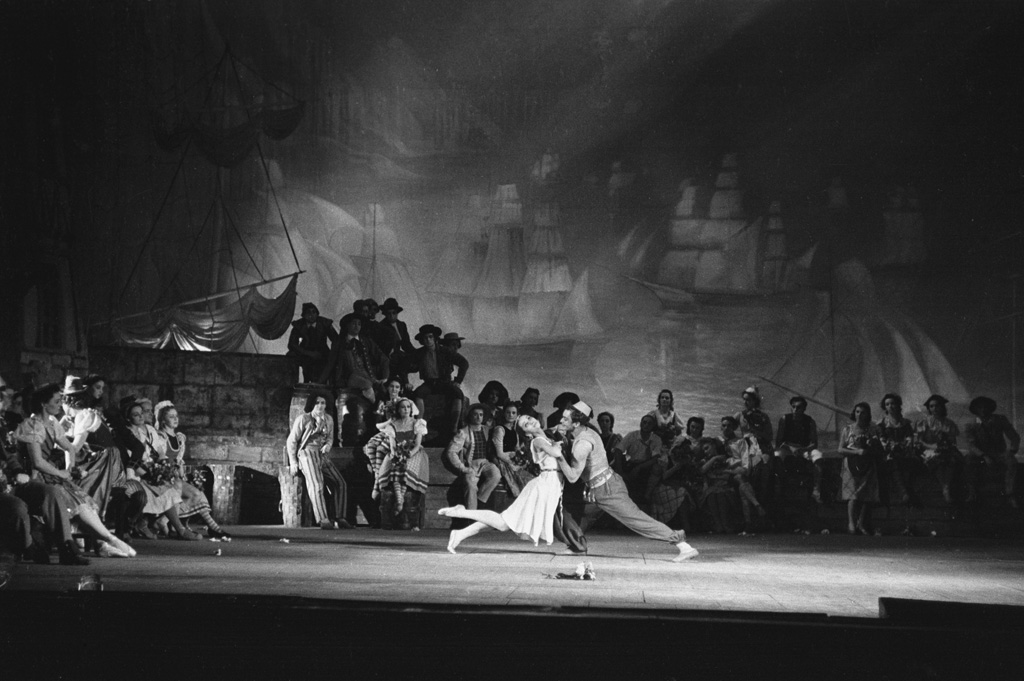

Some of it was interest from my side, and it was also a lot of magnetism from my research over the last few years, which has focused on the musical life in Theresienstadt, one of the big camps during the Nazi period. I also worked for Musica non grata, and that is why I’m very deep in this whole discourse on persecuted artists and artists in exile. This history, of course, brings up the question of democracy, because if you have a dictatorship, like the one during the Nazi period, you see what happens to artistic freedom. We thought about a kind of overall programme for the series, and everybody was very interested in unearthing unknown music, especially music by women composers. In Dresden we did a kind of Theresienstadt-influenced programme of opera and operetta by women. I can’t stand the fuss over the differences between opera and operetta, this idea of supposedly “highbrow” and “lowbrow” art forms; it’s music theatre, period.

Related to that, we also decided to present several works of Ernst Krenek – they will be focused in an event presented at Staatsoper Hamburg in January. He was living in exile in Los Angeles when he composed a very moving work called Pallas Athene weint (Pallas Athena Wept), which was also written during the McCarthy era in the US. Nobody knows it, but it’s fantastic! This opera actually reopened the house in Hamburg after the Second World War. It’s atonal, and presents a dystopic situation exploring the struggle between Athens and Sparta; Athens is the city of democracy and Sparta stands for dictatorship, but Sparta wins. There are these amazing correspondences which exist from that time between Krenek, Thomas Mann, and all the artists living in exile on the West Coast, all of them examining the question of the role of arts and politics. It was also during this time that German emigres were being accused of being communists. I think the history around Krenek’s work is very much tied to the ideas we’re exploring in the series.

Connecting the past & the present

At Dresden’s Palais im Großen Garten in May as part of Opera & Democracy. Photo: Clara Becker

To what extent is this series intended to expand opera’s breadth, especially in an intercontinental sense?

This is a very important question because it highlights two key questions in the Opera & Democracy series: what can opera do for society? And, how can opera itself become a more democratic art form via the means of plurality, diversity, accessibility?. I think it’s very important to bring both sides into a dialogue, particularly with a view to the two opera systems in North America and Germany, which have massive differences. The biggest intercontinental difference is the question of funding, because in the United States, opera is privately funded, and in Germany, it’s state funded. And this is why I think North American opera sometimes seems to be much more aware of the ideas and wishes of the audience. At the Met there is a total change in repertoire, a shift to works which are much more focused on questions of diversity and black culture and history.

For me, one of the most influential experiences so far in the series was my panel discussion with Kira Thurman, an African American musicologist teaching in Wisconsin. She wrote her last book on black opera singers in Germany. She was in our opening session at the Thomas Mann House with Alex Ross and Daniela Levy, a researcher in Los Angeles. Kira’s perspectives were certainly eye-opening for me because discussed the last 100 years of opera from a racial history perspective.

Some opera companies have started installing a wider variety of language selections for seat-back translations – what do you make of that?

The interesting point here is that you really can learn from history. At our opera week in New York City recently, I presented the case of Paul Aron. He was a very successful contemporary composer during the wars, and then the Nazis came and he had to flee to the United States. When he came to New York City in the 1950s he founded an avant-garde opera company and he brought all of the music of the other émigrés – works which had originally been composed in German – with new English versions for American stages, because he was aware of the question of language. It is a barrier; you have to be able to understand the language to participate in the story and the plot. It’s really good to see companies installing these technologies – it’s totally in line with the history of opera.

Invest in education

Kai Hinrich Mülller at the inaugural event of Opera & Democracy at the Thomas Mann House in Los Angeles in January 2024. Photo: Aaron Perez

To what extent does a series like this act as an educational aid?

Well I hope it helps because I’m a teacher myself; I teach professionally here in Cologne. All of my programs are built around students. They are the next generation, and they are much better-placed than I am to do this work, because, well, I’m 39 years old, I have maybe 20 or 30 years in the opera system, but these students have at least 50 more years. So it absolutely doesn’t make any sense to stop education; you have to invest in education because this is the next generation, and if we want to change the system, we have to empower young people and invite them to become part of everything in the first place.

What are you bringing back to the classroom then?

The most important point is that I open a kind of dialogue between their interests and my interests. Very often I am told things relating to casting processes, about not feeling heard in current discourses, that nobody is interested in questions of their generation. We had very intense discussions after October 7th about Israel and Gaza. Sometimes it’s important to listen and to give them the sense that, “Yes, you are welcome, give me your speech, give me your opinion; I don’t have to agree, but I think you have the right to an open and safe space for discussion” – and this is especially applicable to an opera system that is largely not democratic.

Where do unknown composers fit in with the series?

They are very important! One of my most favourite composers right now is Rosy Geiger-Kullmann. We premiered three of her operas during our New York festival. She was a very successful woman composer in Germany, then the Nazis came to power, and it’s the same story as so many others – she fled, first to New York, then to Monterey; her son Herman Geiger-Torel, went to Canada and became a very important figure in opera in Canada through the 1950s to 1970s. Rosie herself composed five big operas. It was hard to believe that we were the first person to perform excerpts from her work during the festival. The 20th century is so full of rarely-heard or played operas.

I think this is another thing I learned from the series: that we really don’t have to be afraid of bringing unknown music back to the stage. Every event in this series so far has been totally sold out. We often play unknown composers, so clearly there is openness in the audience to learning more about new music.

“Opening connections between groups of people who might not normally talk to each other”

(L-R) Composer/conductor Carl Christian Bettendorf, composer Alyssa Regent, and choreographer Miro Magloire in a discussion at 1014 – space for ideas as part of an April event in New York for Opera & Democracy. Photo: Sarah Blesener

What sort of an approach do you take in introducing new works?

We use the opera to open the discussion. For example, in the Thomas Mann House at the launch in Los Angeles, we started with Kurt Weill’s The Yes-Sayer, which is a 30-minute opera about belonging and the power of tradition. Directly after it was when we opened the discourse, first in a panel discussion, then for the audience. My first question was, “If this is a story essentially about saying yes or no, what would you have said?” People in the audience looked at me like, “Why is he talking with us?” but then more and more people engaged, and then we had a great discussion on the question of saying yes or no to traditions, and saying yes or no to opera. In Dresden it was, I think, probably quite simple but very effective storytelling as well.

What effect do you see this series having on the opera world?

Since I started it in January, more and more people are taking notice. Opera companies will knock at my door and say, “Hey Kai, this is interesting. Maybe we can do something together? Let’s think about it.” I see more and more institutions that would love to join us in thinking about the democratic potential of the art form. I think opera is very good for opening eyes, opening emotions, opening the brain, and opening connections between groups of people who might not normally talk to each other – and that is more important than ever right now.