Alexandra Silocea performs with the State Academic Symphony Orchestra “Evgeny Svetlanov” at the George Enescu Festival in September 2019. (Photo: Alex Damian)

Trading one keyboard for another doesn’t mean I don’t miss owning a piano. I used to skip afternoons of school as a youngster so I could sit at home in the quiet calm – just me, the cat, and the sounds. My school principal soon arranged for a piano I could play at school –an old, stiff-keyed upright in the teacher’s lounge – and I did use it, at lunchtime, recess, and sometimes even the much-hated gym (for which I was mercifully excused); it ain’t quite the same as my mahogany grand at home, but it was better than nothing. I naturally gravitate to the instrument, not so much for sentimental reasons as for creative ones; I’m keen to play things as an extension of my musical explorations that include score-reading and a wholly new curiosity toward composition. These are activities that complement, and sometimes refreshingly contrast, my many other creative pursuits. The abstract nature of music, and of music-making, are things I once took for granted; no more.

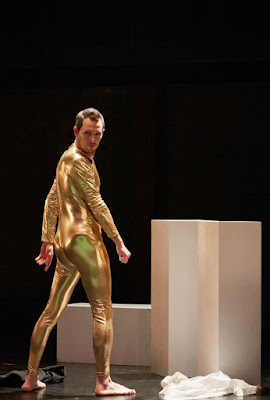

Some performers awaken that place where soul and touch collide, and it’s here that the work of Alexandra Silocea touches a nerve. Her remarkable debut album of Prokofiev Piano Sonatas Nos. 1 – 5 (Avie Records), recorded in a church in England in 2010, is a showcase of delicate touch, knowing timing, lyrical phrasing, and an immensely personal approach to the kaleidoscopic, entirely idiosyncratic piano work of Prokofiev. The album speaks (though more frequently whispers) in ways that tickle the ivories of my own music-filled curiosities and leanings. The ease with which Silocea switches up styles, while still stamping everything with her very own mark, is inspiring. As has been rightly observed, “if Silocea is a talent to be reckoned with and a name to be remembered, it is because she is undaunted by interpretive challenges.” Indeed, but in the most elegant way possible.

This elegance was on full display recently, when Silocea made her debut at the George Enescu Festival in her native Romania, where the Bösendorfer artist performed Shostakovich’s Second Piano Concerto with the State Academic Symphony Orchestra “Evgeny Svetlanov” under the baton of Vladimir Jurowski at Bucharest’s immense Sala Palatului. Along with a very loving performance of the famous concerto (one rapturously greeted by an enthusiastic audience), Silocea also gave a spellbinding encore of Music Box by Anatoly Lyadov, that wonderful delicate touch of hers so nicely suited to the whimsical, chiming tones of the work. It recalled her gorgeous solo work on her Prokofiev album, as well as on the 2015 album (done with cellist Laura Buruiana), Sonatas: Enescu, Prokofiev, Shostakovich (Avie Records), which highlights that flair for individuality, coupled with lyrical flexibility and tonal dynamism. Her 2013 album, Sound Waves (Avie Records), highlights her natural feel for the work of Debussy, Ravel, Liszt, Schubert, and sometimes a lovely combination of the latter two composers. At its release, Gramophone noted that “Silocea proves to be as good a pianist as she is a programme-builder and her playing offers much to savour […] and contours the ‘Der Müller und der Bach’ transcription’s melody/accompaniment in a way that suggests longtime familiarity with Schubert’s original song.” The opening track, Eärendil by the Norwegian composer Martin Romberg, sees the artist carefully highlight the rich, impressionistic writing with her signature elegant touch and deft dynamic coloration.

Silocea got her start as a student at the George Enescu Music School in Bucharest, before going on to the Vienna University for Music and Performing Arts, where, in 2003, she won the Herbert von Karajan Scholarship. In 2008 she made her professional debut with the Wiener KammerOrchester, and a year later, gave recitals in Vienna (at the Musikverein), New York (the Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie Hall), and Paris (Le Salon de Musique). She’s performed at St. Martin In the Fields, and Camerata Pannonica, Finland’s Kymi Sinfonietta, and at this past year’s edition of the Mahler Festival in in Steinbach/Attersee, with bass Matthew Rose. Based in Vienna, Silocea gae a well-received debut with the London Philharmonic in 2012 at Eastbourne’s Congress Hall, performing Mozart’s Piano Concerto No.17 in G Major; Bachtrack’s Evan Dickerson noted “her left-hand touch was particularly notable as it gracefully underlined the melodic material that was imparted with delightful ease by her right hand. The two elements were unified in no small part by good judgement when it came to pedalling.” That good judgment will be exercised when she performs the Shostakovich Piano Concerto 2 again next year over several dates with the Romanian Mihail Jora Philharmonic and Sibiu Philharmonic orchestras, and will be making her debut with the Bamberger Symphoniker under Jakub Hrůša next year; before that, two dates in Ireland, one of which is a concert with Romanian soprano Gabriela Iștoc.

Just before the start of her busy autumn schedule, I sat down with the pianist to chat on the morning following her triumphant Enescu Festival debut. “I’m tired but happy!” she exclaimed, her cheeks flushed pink with joy.

Alexandra Silocea performs with the State Academic Symphony Orchestra “Evgeny Svetlanov” at the George Enescu Festival in September 2019. (Photo: Alex Damian)

Pianos are very much extensions of one’s body for some of us. I remember briefly playing a Bösendorfer years ago, and recall the feeling of its sound really resonating within. Why do you love it?

The sound, and especially the model for yesterday, is very special — the model is called 280VC – Vienna Concert – and the speciality of this one is that the sound is so homogenous, it goes from the lowest the highest very balanced, but with a special tone.

It was very discernible, that tone.

It’s also very powerful — and especially for this Concerto, you need so much strength! You need that for this concert hall too, because you can kind of get lost.

… but you also need lyricism. Its second movement is stunning.

You have to be be careful not to overdo it there, not to fall into cliche. (The concerto) is very often used for film music, and audiences have a preconception of this second movement in particular. I’m so happy Vladimir and I were on the same page with (approach): we were adamant about not going in that sentimental direction. It is sad, but it shouldn’t be sweet.

Bittersweet?

Not even that. It’s very sad. it’s like being in a trance, after this gigantic start and crazy end. In the middle you don’t know where you are.

That isn’t necessarily sad.

Yes — it’s some wordless place. For me it’s like looking through a glass window in the middle of winter on a sunny day, and the glass is not quite clear. That’s my visual image when I play it. And I think the orchestra played it so beautifully. The orchestra… was just amazing. They played the second movement as if with their closed eyes. It was very emotional.

Alexandra Silocea performs with the State Academic Symphony Orchestra “Evgeny Svetlanov” at the George Enescu Festival in September 2019. (Photo: Alex Damian)

This is your first appearance at the festival of your home country.

My family was there. I think this moment will stay in my daughter’s memory. She was humming the theme as I practised. She knew it by heart up to last night; she’s heard it so many times now.

What’s it like to play as a Romanian artist?

It’s a dream come true. I’ve been dreaming of this for so many years! I was eleven or twelve years old when I first attended the festival, in the audience, as part of the music school. I think everyone who does music here dreams of being on the other side of the hall.

And with Shostakovich’s Second Piano Concerto…

It was my first time performing it! The orchestra told me afterwards they had only played this work with men — it was the first time a woman played this piece with them, and they discovered a different way of playing, because it was powerful but yet not… it was a different approach than the male soloists they’ve had, and they’ll remember this. I was quite touched, and so grateful to play with them. What a huge honour. They’re so powerful and I was quite intimidated.

In chats with musicians recently, some think chemistry is either there or it’s not, while others think it can be cultivated. What’s your feeling?

From the beginning having it is the best. If it’s not there and you’re trying and trying, well, it’s better than nothing, but it will never be the same. It’s like with people: with some you click, and with some you don’t, and you feel it from the beginning.

Art is a mirror of life in that way.

Yes.

You have a lot of chemistry with the music of Prokofiev; has it always been there?

For me Prokofiev is one of the gods, and I do feel a deep and special connection with him. It’s always been there, and when the chance of recording a CD came, he was the first composer I thought of. I’m very grateful my label agreed because it was risky for a debut CD, to record five Prokofiev sonatas — it’s not quite the usual! I will continue, especially in 2021, when it’s the 130th anniversary of his birth. It’s not easy, because promoters can be quite difficult.

That seems to be the norm these days; promoters dictate the programming from organizations on tours in order to move tickets.

Maybe sandwich programming is the best — like something popular but also contemporary in-between. We’ll see what will come out of it. Promoters need to trust artists.

And audiences.

Yes, and they need the courage of putting it out there.

Elisabeth Leonskaja performs with the Radio-Symphonieorchester Wien at the George Enescu Festival in September 2019. (Photo: Catalina Filip)

Speaking of passion on display, I saw one of your influences — Leonskaja — recently. How much do you think about them when you play?

I think people who are inspiring you have a huge influence on you. I think there’s always a bit of them in you. Every time I have something very important, Lisa (Leonskaja) always sends me a message before the concert and I know she’s with me, and that’s very special. Somehow it is a responsibility, because somehow the person I am today is thanks to her — we’ve known each other sixteen years now. It’s about moving forwards and keeping all the inspiration I have from her.

That reminds me of a recent conversation I had about the important of humility for artists.

Yes, and Elisabeth is the model for humility and modesty.

The most interesting artists are ones that let themselves be humbled by their art, and translate that humility into life.

You can’t be a true artist if you are not humble and modest. I think you are missing something. I’m just trying to serve the music and the composer, and at the moment I’m quite overwhelmed by the reaction at the festival here, because I honestly didn’t think it would be like this, I didn’t think people would be so touched.

Alexandra Silocea at the George Enescu Festival in September 2019. (Photo: Alex Damian)

People were so excited to meet you at intermission!

I’m so grateful to the festival for the invitation. This moment is one I will never forget. Maybe it’s the beginning of a new era, but… something has shifted, at least inside.

Often that’s how the best kind of art happens: new chapters in art come from new chapters in life. How do you view the art-life connection?

Honestly, how can you separate them? It seems impossible. Being a mother with two kids, I see the change in my playing. It just isn’t possible to separate them. Either a whole personality transposes in the music, or… not. I wouldn’t know how to separate them. I think if they are separate you hear it — you’re not connected to yourself. Maybe it shows later in your life.

… which leads to a quality of the inauthentic.

Yes, especially nowadays.

… and unfortunately not everybody is discerning enough to hear the difference.

I think authenticity today is the most important thing. There are so many of us musicians, and it’s important to just be you. In everything you do, balance is the most important thing, and it’s something I always try to aim for.