This year in classical music and opera saw a lot of hype, a bit of hope, dribbles of desperation and ample ambition. With snow melting out the window and the world both quiet and loud in the post-Christmas, pre-New-Year rush, now seems as good a time as ever to remember, reflect, and of course, to read.

Some of you know this website formally began in 2017 to platform long-form conversations, the kind of thing I felt was missing (and still feel is missing) from mainstream classical music coverage. Fast forward seven years and many conversations later, and there seems to be even more reason for The Opera Queen‘s continued existence than ever. No, I am not x-y-z mainstream outlet; there’s value in being an outsider and to the readership that attracts. This site does not do album reviews, sometimes does live reviews, occasionally offers essays and features on non-classical things – those elements will continue – but mostly it specializes in talking. (Those of you who have met me in real life might not be surprised.) As author Catherine Blyth wrote in her 2009 book The Art of Conversation, “More than words, conversation is music: Its harmony, rhythm and flow transcend communication, flexing mind and heart, tuning us for companionship” – and hopefully a bit of inspiration too.

The paucity of those conversations at The Opera Queen over the last little while is owed chiefly to demands of my day job teaching in a Media and Communications department at a Canadian university, a position that tends to hoover up time, energy, resources. Most Friday nights over past four months found me unable to do little more than Netflix-and-chill (or in my case, 20/20-and-sushi). Rest assured, there are more interviews in store – and more music/theatre/media writing too; some interview chases have been in the works for several months now, and I hope to share the fruits of those efforts soon, and see far more live work, when and if resources allow for such experiences. Let us hope. Nothing brings me alive quite the way live opera does, or can, or ever will – except of course talking with the people who actually do it.

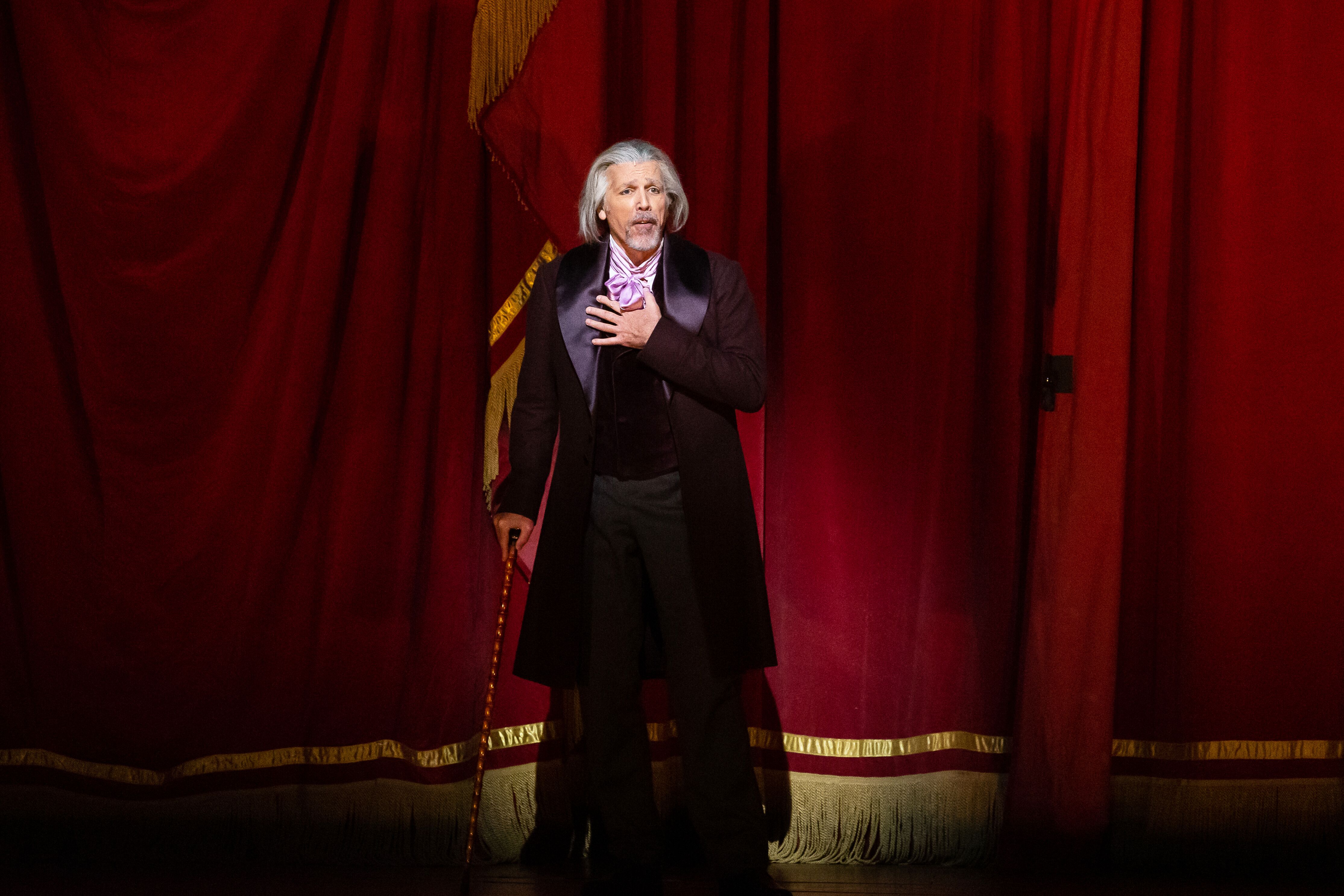

For now, I am staying put and thinking back on the many excellent exchanges published at this website over this past year – conversations with people like Brad Cohen, the General Director of New Zealand Opera; conductors Hannu Lintu and Louis Langree; director Renaud Doucet and designer André Barbe. I also spoke with Cambridge Professor David Trippett about editing Wagner In Context (the c-word!), bass Brindley Sherratt about his (overdue, brilliant) album of songs; baritone Ludovic Tézier backstage at Opera Bastille. For these, and for all the others, I am wholly grateful. I am equally filled with thanks for my readership, and their enthusiasm, passion, and continuing commitment, both to my work here, and to the art forms we all cherish. From my heart: merci beaucoup, vielen dank, mille grazie!

A late-December reading list amidst the snow and cold of the Northern hemisphere seems like a good thing, along with two recipes. Enjoy, and may we all find a little bit of quiet, and a little bit of peace, this holiday season.

Berlin Woes

Recent cuts to the budgets of Berlin’s arts institutions have polarized opinions; while cultural leaders repeatedly underlined (in public and before performances) the centrality of arts institutions to both the economy and a broader national identity, Berlin’s Mayor, Kai Wegner, stated that prices for classical events should be raised and that it isn’t right how, in his view, ‘the shop assistant in the supermarket, who probably rarely goes to the State Opera, uses her tax money to subsidise all these tickets.” / „dass die Verkäuferin im Supermarkt, die wahrscheinlich eher selten in die Staatsoper geht, mit ihrem Steuergeld diese Eintrittskarten allesamt mitsubventioniert.” (“Kai Wegner gibt Mentalitätstipps“, TAZ, Rainer Rutz, 1 December 2024) Wegner also implied support for a more North American-style system with far less government dependency by arts organizations and far more in terms of commercial programming.

German daily TAZ took Wegner at his word and asked cashiers in Berlin about opera and ticket prices. What did they say? Well, you’ll never guess. (“Gehen Kassiererinnen in die Oper?“, TAZ, Katja Kollman, 6 December 2024)

Scores & Violins

Just what do orchestra librarians do, and how does their work differ from that of other librarians? San Francisco Classical Voice has a wonderful feature on the under-appreciated position which hosts insights from San Francisco Opera Orchestra librarian Carrie Weick, Oakland Symphony / Marin Symphony / Monterey Symphony / California Symphony librarian and musician Drew Ford, and San Francisco Symphony’s principal orchestra librarian Margo Kieser, who says her past work as a musician, especially transposing scores for singers, was definitely helpful. The feature also explores the ins and outs of critical editions, how the job has changed, working with concertmasters, and interactions with various music figures past and present, including Jesús López Cobos, Sir Mark Elder and John Adams. (“The Scorekeepers: Orchestra Librarians and Their Work“, San Francisco Classical Voice, Lisa Hirsch, 4 December 2024)

Keeping in the realm of education: various residents of the rural Scottish island of Great Cumbrae have been learning how to play the violin and viola for free on instruments loaned by local organizations. The adult learning initiative is part of a PhD project on community music led by violist/educator Arianna Ranieri, who says participants have been “turning up every week with a hunger to learn– and have even begun have jam and practice sessions outside of the Saturday classes– it is a teacher and researcher’s dream, and shows how important it is to have these opportunities for adults in rural areas.” (“Free violin lessons enrich adult learners’ lives in rural Scotland”, The Strad, 5 December 2024)

Still with strings: Following the sudden passing of György Pauk in mid-November, music writer Ariane Todes published pieces of her two conversations with the acclaimed violinist and teacher. Among the many nuggets therein are Pauk’s insights into technique (“The thumb should always be a little bent”), the role of singing (“Timing comes from breathing, which is why the best way to understand a phrase is to sing it.”), the importance of playing Bartók (“it’s helpful to be Hungarian but you don’t have to be”), teaching approach, practice habits, what the operas of Mozart offer, and much more. Pauk’s reminiscences on the “once-famous Hungarian violin school” and its approach are particularly touching. (“Interview with György Pauk“, Elbow Music, Ariane Todes, 19 November 2024).

Viennese Delights

January anywhere can be dreary, but January in Vienna seems a bit less daunting thanks to the city’s multiple cultural offerings, including some sunny-sounding operettas. Johann Strauss II’s Das Spitzentuch der Königin (The Queen’s Lace Handkerchief) will be presented at Theater An Der Wien, the very spot the work premiered in 1880, under the baton of its composer. The piece is a political parody with a thinly-disguised monarchy engaging in misadventures with the poet Cervantes, who derives inspiration for his real-life Don Quixote along the way. The work includes the famous “Rosen aus dem Suden” (Roses from the South) waltz. Königin previews on 5 January before its formal opening on 18 January, and runs through the end of the month.

Over at the Volksoper, Offenbach’s “science-fiction operetta” Die Reise zum Mond (A Trip To The Moon) is on now through 31 January. The work premiered in Paris at the Théâtre de la Gaîté in 1875 (as Le voyage dans la lune) and has its basis in Jules Verne’s 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon. The Volksoper’s eye-catching production (by director Laurent Pelly) explores themes of climate change and youth empowerment; it opened in October 2023 to raves, and features members of the company’s children and youth choirs performing in multiple roles. Also at the Volksoper is Im weißen Rössl (The White Horse Inn), by Ralph Benatzky along with multiple collaborators, both musical and text-based. Based on a highly popular play by Berlin theatre artist Oscar Blumenthal, the work revolves around a waiter’s longing for his boss at a busy summer resort; the Volksoper’s production (by director Jan Philipp Gloger) explores the perils of tourism. Rössl opened earlier this month and runs to the end of January.

Along with operetta, uplift arrives via Philharmonix, who will be giving a concert at the Konzerthaus on 14 January mischievously titled “Guilty Pleasures“. A collective composed of members of both the Vienna and Berlin Philharmonic Orchestras, their fun, zesty mix of classical, jazz, and lyrical works that evoke the city’s illustrious coffeehouse culture, especially during the Belle Époque. The January date is the second in a series of three Vienna appearances the group are making throughout the season; their next appearance in the city is set for April.

Just as fun: Prokofiev’s Peter And The Wolf is set for a series of performances, in a staging by Martin Schläpfer, ballet director and chief choreographer of the Wiener Staatsballett, and featuring youth members of said ballet corps. The production joins a long history of Peter presentations, one that has included recordings, orchestral performances, and animation, including a clever 2023 retelling narrated by Irish artist Gavin Friday and animation by Bono released last December. The Wiener Staatsoper presentation with its young dance corps happens at Wiener Staatsoper’s new NEST facility (aimed at junior audiences), and runs from the end of January through to 9 February.

Sound Of The Season

‘Tis the season of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, hurrah! First performed in Leipzig between Christmas Day 1734 and 6 January 1735, Bach had actually composed the gorgeous six-cantata oratorio (made up largely of much parody, or repurposed, music) a decade earlier. Among the many performances to be found online, those done by Netherlands Bach Society caught my attention; the Dutch group released a fascinating introduction to the work last year, and more recently shared videos of the first three cantatas of the oratorio, all with English subtitles. Once you know the words to the chorales, you cannot help but sing along, but just in case you need some pointers, here’s the full text (with English translations), courtesy of the Bach Cantatas website. Jauchzet, frohlocket!

Musical keys have personalities (or so goes the thinking) and Bach’s Oratorio is centered around the key of D Major (“the key of Hallelujahs“) – so what’s your personal key? What does it say about you? Find out with this fun little quiz, courtesy of Van Musik. (“Tonart-O-Mat“, Arno Lücker, 27 November 2024) Mine is apparently D-flat major, the key of Debussy’s “Claire de Lune” (and, apparently, “eine wunderbare, hochromantische Tonart!” 😀 ).

Yum

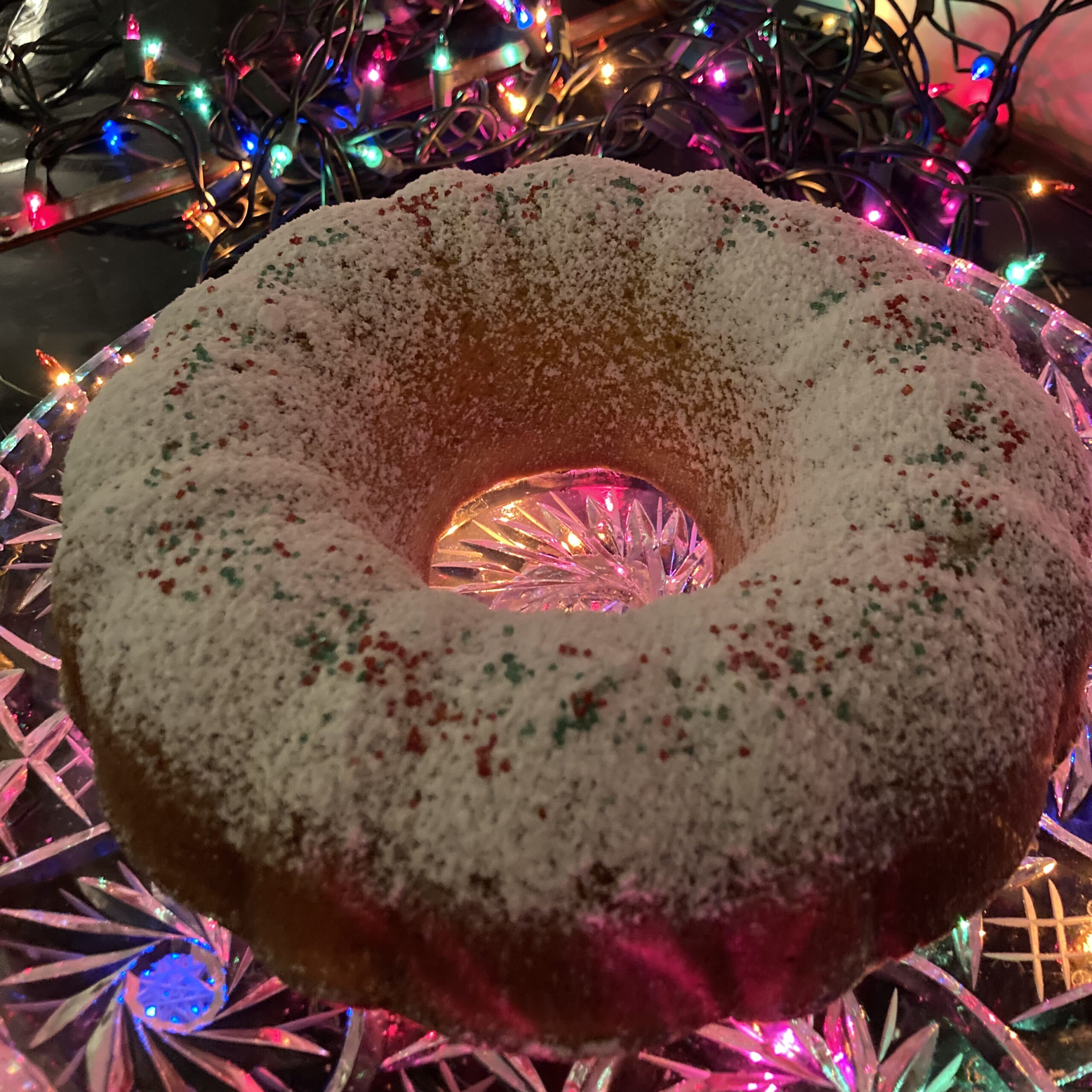

Nigella Lawson’s eggy vanilla cake, chez moi. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without written permission.

Once a prolific holiday baker, I am now a confirmed rarely-ever baker, but for pizza and the occasional loaf of hearty bread; one recent cold day I found myself hankering, not for sweets but for process, texture, aroma. The sensual aspects of baking, together with its demand for patience and respect for step-taking, made for a lovely late-afternoon pursuit and a rather nice result. (“Spruced-Up Vanilla Cake“, Nigella Christmas, 2008). I don’t have Nigella Lawson’s fancy Christmas tin, but my trusty bundt pan did nicely. Also: don’t fret if you don’t have (enough) yogurt; a bit of vinegar dropped into heavy cream (and left to sit for twenty-ish minutes) does the trick.

This year’s Chanukkah happened to fall on 25 December, but as I had the cake (above) I decided against making homemade doughnut or latkes, the latter being something I once produced in copious quantities using Lawson’s recipe from her 2004 book Feast as a guide. This recipe for Kartoffelpuffer, which uses flour in place of the more traditional matzo meal (which I would still use), is easy, and… mmm, lecker:

New Year’s Eve may well be a Fledermaus affair, enjoyed with a bit of smoked fish, some salad olivye, pickles, pelmeni, and a glass of bubbles. Until then: thank you, dear readers, for your continued support and trust, and here’s to more talks, thoughts, and life-giving performances in 2025!