Photo: Bo Huang

Krisztina Szabó is a busy lady.

A recent whirlwind trip between her home city of Toronto and Berlin left the mezzo soprano jet-lagged but, one might suspect, quite happy; within the space of a few days, she’d made her German debut at the annual Musikfest with the acclaimed Mahler Chamber Orchestra, performing the work of Sir George Benjamin under his very baton. Considering the number of engagements she’s had over the last few years, it’s probably fair to say she’s used to the pace.

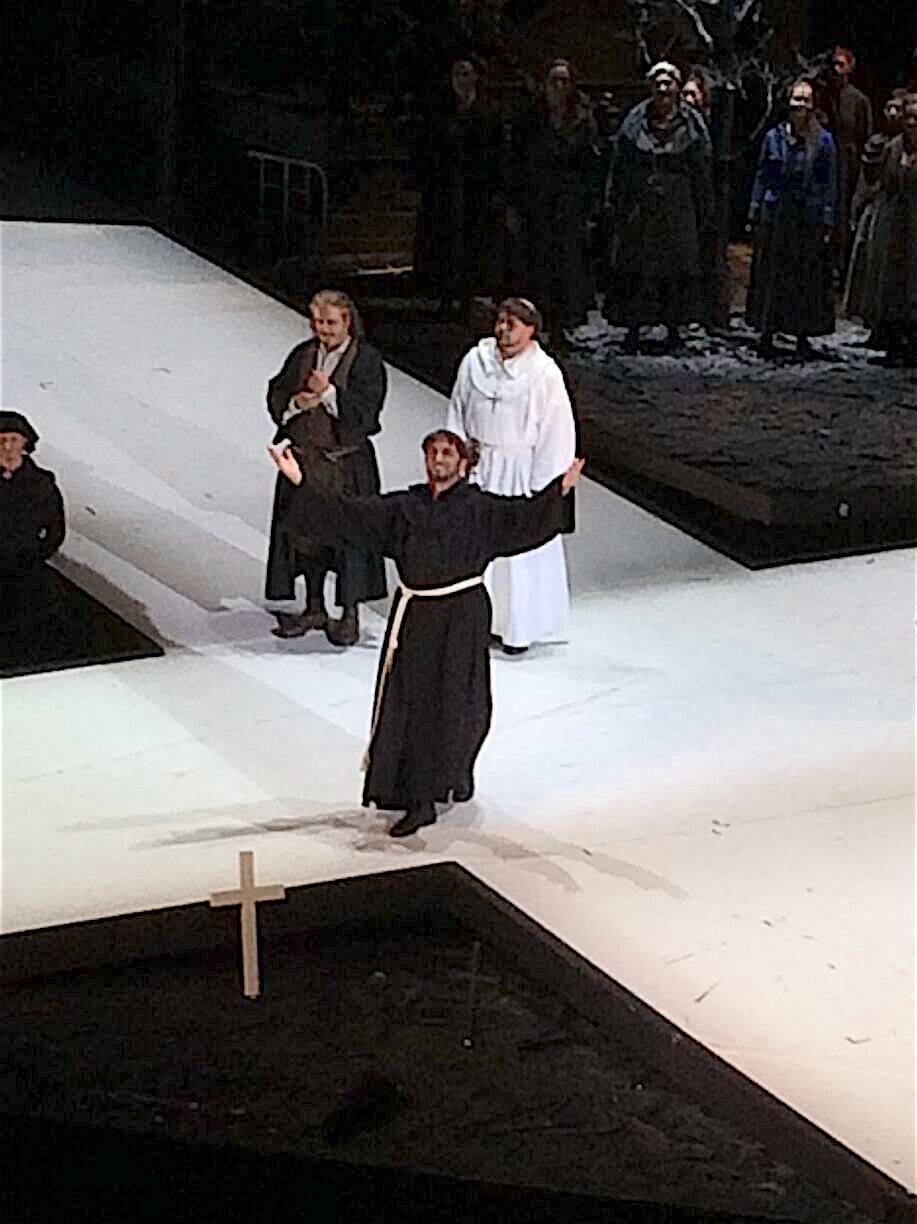

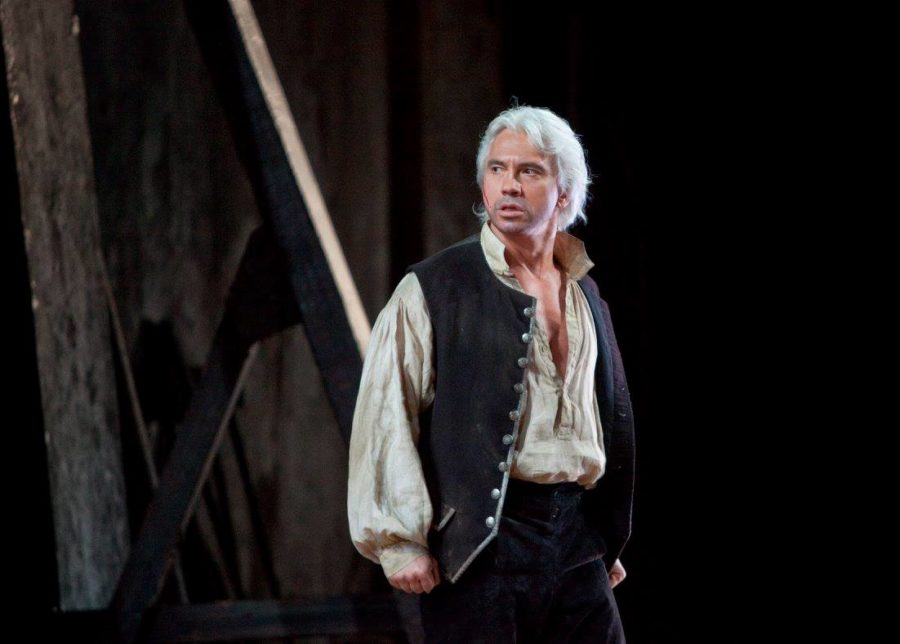

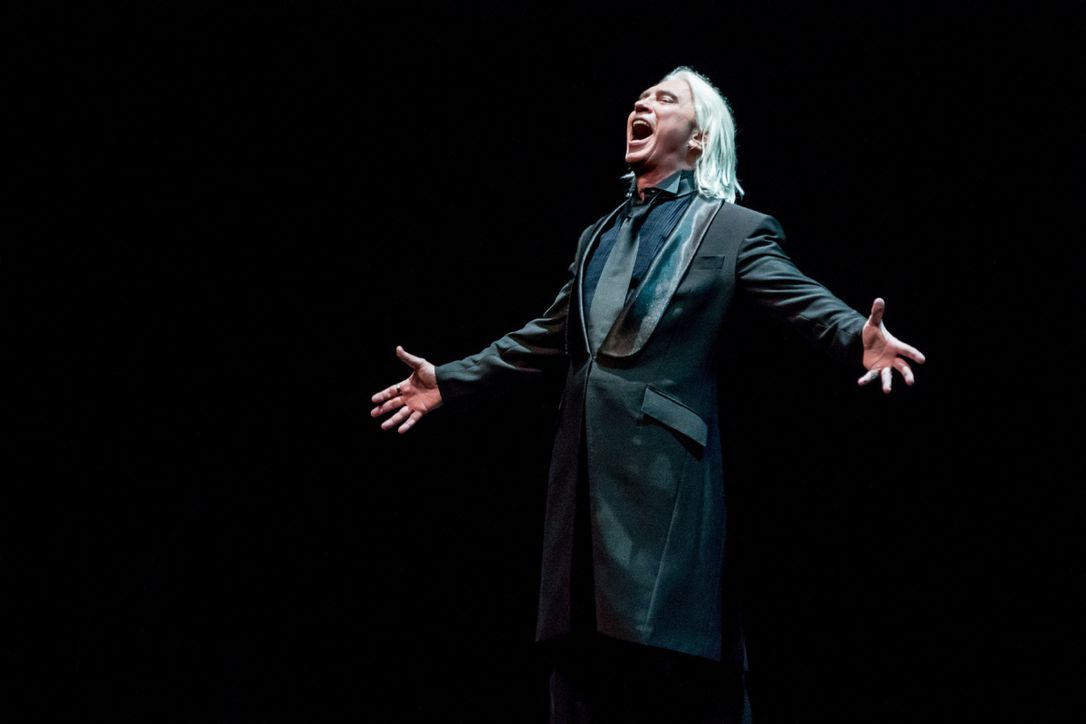

Since postgraduate studies at Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London, she’s had a busy career with incredible highlights, including working with celebrated Russian baritone with Dmitri Hvorostovsky in Don Giovanni Revealed: Leporello’s Revenge, as soloist with Plural Ensemble in Madrid under the baton of composer-conductor Peter Eötvös, and having a part composed by Benjamin specifically for her voice (more on that below). She’s worked with a number of celebrated institutions including Wexford Festival Opera, the Mostly Mozart Festival, L’Opéra National du Rhin, and the Colorado Music Festival (just to name a few), as well as Canadian companies including Vancouver Opera, L’Opéra de Québec, and Calgary Opera. Her passion (and talent) for new work is clear in her bio, having worked with a number of organizations specializing in contemporary repertoire, including Ensemble Contemporain de Montréal, Soundstreams, and Tapestry Opera, and living composers including Anna Sokolovic, James Rolfe, and Aaron Gervais, as well as the aforementioned Eötvös and Benjamin.

Phillip Addis and Krisztina Szabó in the Canadian Opera Company’s 2015 production of “Pyramus and Thisbe / Lamento d’Arianna / Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda” (Photo: Michael Cooper)

In 2015, Szabó sang no less than three leading roles one show production, a triumvirate vision that combined Claudio Monteverdi’s 17th century Lamento D’Arianna and Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda with Barbara Monk Feldman’s 2009 Pyramus and Thisbe, directed by Christopher Alden. In my review I referenced Szabó’s compelling stage presence, admiring her range, projection, chemistry with co-star Phillip Addis, and amazing versatility, both vocally and physically (at one point she was required to sing lying flat on the stage floor), though what has really stayed with me since has been her innate sense of theatre; the haunted look she would give Addis at points (the production was a fascinating look at the battle of the sexes), her loose physicality, the keen, cool balance of control and vulnerability, combined with a lovely mahogany-meets-cognac vocal tone, are qualities that give her a special place in the opera world.

That was reiterated in her recent performance with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, in Benjamin’s 2006 chamber opera Into the Little Hill: that same haunted look, an immense energy, a fierce vocal prowess. Szabó, who also speaks fluent Hungarian and is a member of the voice faculty at the University of Toronto, has drama running through her veins, and her work with the MCO (who matched her intensity with ferocious intelligence and quiet elegance) was a highlight of this year’s Musikfest. She has, she admits, done “a ton of Benjamin”, including performances of his celebrated 2012 opera Written on Skin (twice in concert and once in an Opera Philadelphia production), as well as his new work, Lessons in Love and Violence, at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden (where it made its world premiere in April) and at Netherlands Opera, where she worked alongside fellow Canadian singer (and contemporary repertoire virtuoso) Barbara Hannigan, who has a close relationship with the work of Benjamin herself. The same goes for the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, the celebrated troupe whose repertoire ranges from baroque to contemporary compositions. Founded in 1997, the orchestra premiered Written on Skin in 2012 (the composer/conductor has said he had heir specific sound in mind when he wrote it) and they’ve also toured the work internationally, in both opera and semi-staged concert versions. Into the Little Hill, though presented in concert at Musikfest, lost none of its dramatic power (the work is based on the fairytale of the pied piper), with Szabó and soprano Susanna Andersson making a fine, fierce duet onstage, their delivery crisp and careful, their characterizations gripping.

Prior to the performance, Szabó made time to chat about Benjamin, working with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, and what she takes away from here whirlwind trip to Berlin. (It doesn’t include beer, I don’t think.)

What is it you find so rewarding about Benjamin’s work as an artist?

I find the colors he gets from the orchestra one of the most striking things about his scores, and you’ll find that again in Into the Little Hill — it’s just remarkable. It’s so delicate and yet it can be so full and impactful as well. It’s quite striking. This one is scored for contralto, which I am not, so for me it’s a on the low side but the low stuff is lightly scored, so it’s doable. Written on Skin has some remarkable passages — some are quite low, some are quite high; it’s a large range. It’s rhythmically really, really detailed, just like his scores. I love that kind of stuff — I love rhythmic complexity, it’s like a sudoku puzzle I have yet to figure out. That’s my anal-retentive nature coming out, maybe.

Some of his scores also feature a cimbalom.

Yes, Written On Skin and Lessons in Love and Violence both have the cimbalom. The first time I was looking up the score for Skin, I was like, “Hey! That’s the instrument of my people!”

What does that add?

It’s an exotic color, it’s that twangyness. Into the Little Hill has a banjo too, but the cimbalom has this cut-through sound; the violins, when bowed, have this lyrical sound, and plucked they have another certain sound, but the cimbalom has a certain cut to it, which gives it this exotic flavor.

Photo: Matthew Lloyd

What is Benjamin like to work with?

I have worked with a lot of living composers, not at his level obviously, but working with him is a particular adventure because that man likes to rehearse! And if you look at his score it’s incredibly detailed. You have to be on your toes and be super-prepared, but he always appreciates musicianship and preparation and detail; if you give that to him, then it’s great. He’s such a sweet man, actually. But at my first rehearsal for Written on Skin, I thought, “Oh, I don’t have as much to sing” — we had a two-hour call — “we won’t use all the time up.” But I was sweating by the end; we used every bit of it and I thought, “This guy likes to rehearse!” He doesn’t smile necessarily, he’s very serious, very focused, very British. After a few rehearsals he starts to loosen up, and it’s like, “Okay, he doesn’t hate me!”

And you’ve developed something of a relationship now because you have worked together a few times and he knows how he can push you.

Yes he does, for sure. I mean, the part in Lessons in Love and Violence was composed specifically for my voice, which was kind of cool — it was written particularly to my strengths, which was fun. That’s not going to get old!

How has working on Into the Little Hill stretched you creatively?

Vocally it’s stretched me for sure! It’s scored for contralto, so I am trying to find my inner contralto. I live higher — I’m a high mezzo, I straddle soprano repertoire as well, so making friends with my middle-low register has been interesting – a little scary, but a welcome challenge. In terms of the drama, I play several characters. Both soprano and mezzo have to switch and make quick changes (between various characters) and (Benjamin) wants those changes really sharp, to make it clear for the audience.

And you’re doing this as part of your Musikfest debut…

Yes, this is a wonderful opportunity for me. I am thrilled to be here, but for me the biggest hurdle is making sure that George likes it. When you have the composer standing two feet in front of you, he’s the audience I am trying to impress the most.

Mahler Chamber Orchestra (Photo: © Manu Agah)

What’s it been like working with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra? They have such a celebrated history with Benjamin.

The quality of the musicianship is extraordinary — Susanna Andersson (soprano) was saying during rehearsals, “They are playing things I cannot believe they are playing!’” As detailed as George is with the singers, he is super-detailed with the instrumentalists, picking them apart, so it’s very clear what they’re doing. Some parts of the score have extremely complicated passages for them to play. He’s not a showman conductor; he’s clear and detailed and precise and delicate.

That delicacy was what I found so amazing when I saw him lead the Berlin Philharmonic recently; it was so very noticeable and gave the music so much more depth and color.

Yes, and we haven’t had a hell of a lot of rehearsal for this, but… that man has bionic ears! When someone plays a wrong note somewhere: “Was it you?” He can pick it out. I know conductors can have that ability, but to take the most delicate chord and pick out, immediately, what needs to be worked on… he’s very organized and detailed about what he wants, and how to get something.

… whether it’s the Berlin Philharmonic or the Mahler Chamber Orchestra.

He said, “Oh they’re reading this for the first time” today and I went “WHAT?!” It was already at a level… it did not seem they had just cracked the score.

Photo: Bo Huang

What kinds of things are you already taking from this experience in Berlin, especially in your role as a teacher?

I think about my students more often when I perform now. I think I take away the idea of stamina for sure. You hear students complain a lot: “I don’t have time to do that” and “I’m tired!” Well, I haven’t slept, I’m jet-lagged, I’ve worked six-hour days the last two days straight on a piece that is stretching me vocally, balance the stamina vocally while giving the composer/conductor what he wants. These are the things they have to learn. There’s vocal technique, but there’s all the other stuff, and it’s still an ongoing process. What I tell them is, learning singing is a lifelong thing, because it will change daily: how you feel, how you’ve slept, what you’ve eaten, if you’re well, if you’re unwell, if you’re upset, if you’re happy. All these things factor into how you sing on that day and it is a lifelong process of how to deal with that in any given moment. You don’t know what you’ll wake up with but you have to get the job done, and I am all about getting the job done. It’s about managing what’s important.