My recent blog silence isn’t so much for lack of what to write about, but what to focus on. Choose one thing’ has been a constant mantra throughout my life. Social media has been both a blessing and a curse in terms of widening perspective and simultaneously driving home a tendency to un-focus; no wonder being on an airplane recently, with laptop purposely packed away, produced a weirdo mix of panic and relief.

Settling on one thing was enough of a challenge, but once I chose my topic, there were several developments that occurred with incredible rapidity, forcing updates and edits. And then, I had second, third, eleventh, twenty-eighth thoughts on posting it. I don’t like writing about things I haven’t seen, much less giving play to conjecture. But the drama at the center of the Broadway production of Spider Man: Turn Off The Dark has been weighing heavily on my mind -for the way it’s been treated in popular media, for the reports I’ve received from those who have seen it, from the things shared with me from those who’ve worked with its director, and, mainly, for my absolute love of the theatrical medium, and the close-knit family unit that squals, squeals and shrieks at its crying, bleeding, puking, unquestionably messy core.

As reported lastnight, director Julie Taymor’s role has been altered -or, to be frank, greatly diminished; the New York Times offered a “precipitous” headline on top of a solid piece of reporting, though the piece had a noticeable undercurrent of sadness that perfectly reflected my feelings at the situation. Theater is nothing but a sum of its creators/cast/crew parts, a singing, dancing Frankenstein monster that might provoke a few tears, jeers, cheers, but always, hopefully, a gilded memory framed in sighs, frills, & the tunes you’ll hum the next day. Show producers Michael Cohl and Jeremiah Harris along with composers Bono and The Edge felt Spider Man: Turn Off The Dark needed more neck bolts, some matching arms, a solid pair of shoes to walk in (though not of the “furious” eight-legged variety) and more smoochy time with the proverbial Mrs. Frankenstein. I briefly referenced the show in a past blog in which I attended The Fantasticks, and observed how low-tech it must’ve been to my companion, who’d been to the Foxwoods Theater not long before. I felt a little ripple of excitement spotting the ads and theater marquee recently. Something new is going on there, I thought. It’s hard, but so is life. So is theater. And to some, theater is life. Doctor Frankenstein had to work hard to imbue his creature with it.

The hyper-critical response to Spider Man: Turn Off The Dark is due, in part, to the starry names attached to the project; its composers are well-known rock dudes, while its director is the woman behind one of the most original pieces of theater ever produced. Famous rich people are easy targets, especially when it comes to a public spectacle involving putting one of American pop culture’s most famous (and beloved) figures onstage. Through death, bankruptcy, accolades, accidents, an addition, a withdrawl, and big, name-making snark, the show has chugged on, drawing big crowds and averaging good weekly totals. The ocean of words written about the show are a truer reflection of the lack of awareness in the general public for how theater works (or should work) and is less about the show itself, which most people who are writing (journalists aside) haven’t seen. It also shows an awesome ignorance towards the nasty politics of playing on Broadway, where artistic integrity and creativity are frequently last on the list of priorities for a Really Big Show (ROI is #1, in case you’re wondering). It all has to start somewhere -any show, large or small does -and once the germ of the idea has been sewn, the care and cultivation come when words first hit the screen. Setting: a bare stage, or, Setting: Peter Parker’s bedroom. Whatever the case, it starts with the words.

And the weak writing in Spider Man: Turn Off The Dark has been a source of concern for professional theater writers and audiences alike. This was the main complaint of my friend who’s seen it, and it’s been highlighted in the vast, bitter sea of sniping. I had a long conversation with a theater-producer friend recently, about the demands of staging a new live show, and about the pressures from investors, who frequently want to see a quick return on the money they’ve put out; with the pressure and intense public scrutiny this show is under, it seems at least plausible that the written aspect got overtaken by the fancier, much-more-hype-friendly-and-frankly-sexy special effects. He flies! He leaps! He lands on balconies! He’ll be swooshing over your head! As was pointed out in an informative article on theater-flying recently, flying = sales. Might it be a fair suggestion that Julie Taymor, for all her intense creativity, felt more pressured to focus on the visual (ie money-making) aspects of the show, and less on the actual writing? Maybe. Or maybe not. She had a decade, goes the accusation. She’d never written before. She didn’t want to make any changes. She was forced to walk the plank. Blahblahblah.

I’m left, after observing and following all these dramatic (and probably truamatic) developments, asking one small question: did anyone at the beginning suggest an outside voice (like a dramaturge) was needed? Or did the situation become like a cartoon snowball, rolling down a hill, picking up toboggans, trees, feckless bystanders, in its raging, manic race to inevitable explosion?

It’s all conjecture, and it’s worth remembering that much of what’s coming out now about the show is just that. Julie Taymor didn’t experience a soft landing, and I doubt anyone associated with the show will at this point. But we can only guess. It’s all a series of web-laced question marks. I’m going to hold off on making any firm judgments on Spider Man on Broadway until I see it. For the sake of everyone involved, I hope they, as a collective Dr. Frankenstein, can get their creature on its feet. Some of us still want to believe.

Update: the new opening of Spider Man: Turn Off The Dark is June 14th.

Life has a way of turning out exactly like you didn’t plan. And yet it’s through the labyrinth of choice that we arrive at a new destination.

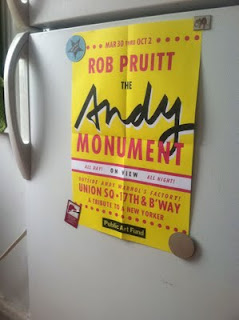

Life has a way of turning out exactly like you didn’t plan. And yet it’s through the labyrinth of choice that we arrive at a new destination. There’s something curiously inspiring about this story. It got me thinking about the value we place on our activities, especially in the age of digital, where (especially as writers and artists) there is an expectation of “free” -a culture that has become a kind of monstrously growing pudding, one that keeps being fed by people who should know better. Whither worth? Everyone has to make a living -and has a right to. It can be, as Warhol serves to remind us, mundane, fantastical, or a mix of both (proudly), but we live in a culture where money is a vital form of energetic exchange. Those 15 minutes aren’t enough -you should either make money from it, or pay for it. Right? Wrong? It’s worth pondering, especially in an age where we choose to take and give things -talents, time, energy -without a thought. I wonder what Warhol would say.

There’s something curiously inspiring about this story. It got me thinking about the value we place on our activities, especially in the age of digital, where (especially as writers and artists) there is an expectation of “free” -a culture that has become a kind of monstrously growing pudding, one that keeps being fed by people who should know better. Whither worth? Everyone has to make a living -and has a right to. It can be, as Warhol serves to remind us, mundane, fantastical, or a mix of both (proudly), but we live in a culture where money is a vital form of energetic exchange. Those 15 minutes aren’t enough -you should either make money from it, or pay for it. Right? Wrong? It’s worth pondering, especially in an age where we choose to take and give things -talents, time, energy -without a thought. I wonder what Warhol would say.