Lyubov Petrova is an artist whose work is impossible to place in a tidy little box; as you’ll read, that’s just the way she likes it. An immensely gifted soprano with a knack for fusing singing with storytelling, Petrova has an immensely varied opera history, from a smart, note-perfect Adele in Stephen Lawless’s 2003 production of Die Fledermaus at the Glyndebourne Festival to a raging Queen Of The Night in Kenneth Branagh’s fascinatingly recontextualized cinematic adaptation of Mozart’s Die Zauberflote (2006). She’s also ace at epic concert repertoire (including Rachmaninoff’s choral symphony The Bells and Brahms’s Ein deutsches Requiem), as well as more intimate work, a talent she poetically showcases on her 2017 album of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff songs.

A winner of the 1998 International Rimsky-Korsakov Competition and 1999 International Elena Obraztsova Competition, Petrova trained at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow before joining the Metropolitan Opera’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Programme, and has enjoyed numerous Met appearances, including as Zerbinetta in Ariadne auf Naxos (her Met debut), Sophie in Der Rosenkavalier, Pamina in Die Zauberflöte, Norina in Don Pasquale, Sophie in Werther, Nannetta in Falstaff, and Woglinde in Das Rheingold, to name a brief few. The New York-based soprano has performed with numerous other North American outlets too, including Dallas Opera, LA Opera, Pittsburgh Opera, Houston Grand Opera, and Washington National Opera, and has performed at various festivals worldwide, including ones Glimmerglass, Glyndebourne, and Spoleto, at the Bellini Festival in Catania, the Pergolesi Festival in Jesi, Italy, and the BBC Proms.

Petrova has appeared with numerous prominent international houses including Opéra National de Paris, Teatro Real Madrid, Teatro San Carlo di Napoli, Teatro Massimo in Palermo, Dutch National Opera, New Israeli Opera, Korean National Opera, the Bolshoi, the Kolobov Novaya Opera Theatre of Moscow, and the Teatro Colón (Argentina). She’s also done a range of symphonic and concert work (music of Bach, Mozart, Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini, and Bizet, to name a few) with an assortment of orchestras including the Hong Kong Philharmonic, the Orchester Pressburger Philharmoniker, the Moscow Chamber Orchestra, and the Russian National Orchestra. One look at such a varied history reveals an impressive and entirely consistent development into vocally heavier repertoire, while still keeping a firm foot in Petrova’s place of origin (figuratively and literally) – a tuneful and fleet-footed spot with an ever-present edge of laser-like authority.

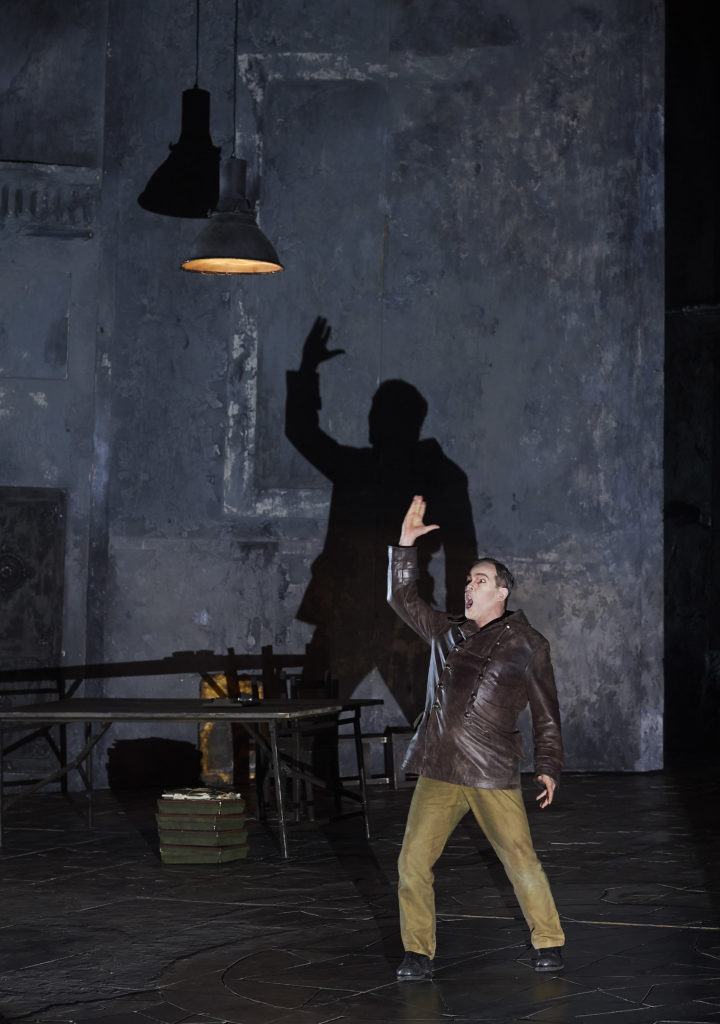

Petrova first caught my attention through her remarkable, gleaming, in-concert performance in Prokofiev’s Semyon Kotko with the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic at the Concertgebouw in 2016, where she brought a thoughtful lyricism to Prokofiev’s angular, driving score, making the fraught nature of the work – and its deceptively simple characters – warmly, recognizably human. During the opera’s composition, the opera’s would be producer, Russian theatre artist Vsevolod Meyerhold, was arrested and later murdered as part of the Great Purge; at the time of its 1940 premiere its perceived importance was strongly connected to a “Soviet opera” aesthetic (despite the frisson between its obvious melodramatic and moralistic scheme of social realism), a perception strengthened for its being based on Valentin Kataev’s 1937 novel, I, Son Of The Working People. The complicated nature of the work, combined with its even more complicated (and tragic) composition history (involving the sudden disappearance of Meyerhold as well as a political pact that necessitated changing the bad guys from Germans to Ukrainian nationalists), plus its (predictably) myopic reception (celebrating its ideology while ignoring the music) meant the opera wasn’t performed anywhere between 1941 and 1958, and only entered the repertory of the Bolshoi in 1970; Prokofiev would later compose an orchestral suite based on the opera. It is notable when singers can integrate this sort of charged history into the very seams of sound, so that performances become much greater than the sum of their individual parts; such visceral interpretative artistry is what Petrova – and indeed the entire cast – did with such affecting results in Amsterdam in late 2016.

Petrova’s vocal warmth is something of a signature. Her tonally shimmering, golden-hued turn as Freia in Wagner’s Das Rheingold was truly memorable, part of an in-concert presentation in early 2018 with the London Philharmonic Orchestra featuring Michelle de Young, Matthias Goerne, Matthew Rose, and Brindley Sherratt, under the baton of conductor Vladimir Jurowski; she performed the role again the role later that same year with the Odense Symfoniorkester (Denmark) with conductor Alexander Vedernikov. 2018 also saw Petrova sing the role of Marfa in Bard Music Festival‘s presentation of The Tsar’s Bride and perform works from Shostakovich’s 1948 song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry as part of Music@Menlo. 2019 opened with the music of Mozart, with Petrova taking on Countess Almaviva in Le nozze di Figaro with Florida Grand Opera. Freia returned with an October 2019 in-concert presentation of Das Rheingold in Moscow, again with Jurowski but this time with the State Academic Orchestra of Russia Evgeny Svetlanov.

Petrova’s album Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff: Songs (Nimbus Records), recorded with pianist Vladimir Feltsman, showcases this vocal excellence, and nicely displays another side of the multi-faceted artist, a silken, soft suppleness that delights the ear. Her caressing of the text, careful phrasing, and thoughtful tonal intonations betray a deeply sensitive artistic sensibility able to quickly adjust itself according to both the tangible and intangible elements of music-making. In 2017 music writer Ken Herman noted of Petrova, that “(w)hether she sings of love, death, sorrow, […] she never merely sings about these states—she incarnates them and forces her listeners to confront them.” That quote was immediately related to the soprano’s performance at that year’s edition of the La Jolla Music Society Summerfest, but It’s an observation that applies just as much to her approach to the material on the Tchaikovsky/Rachmaninoff album, and, more broadly, her artistic approach overall. Petrova has a very palpable musicality, embodied in a clear love of text; the way she caresses Pushkin’s words in “The Muse” (from Rachmaninoff’s 14 Romances, Op. 34), for instance, blends a knowing and natural affinity for integrating theatre and drama. Listen to the way she hangs on the word “пастухов” (shepherds) here: simultaneously a dramatic arc and a thoughtful reprieve, Petrova’s approach, together with that of Feltsman, embodies Richard D. Sylvester’s observation of the work, that “the singer must convey the declamatory phrases with expression and warmth and the pianist must lead, gently but firmly, not allowing the song to stall.” (Rachmaninoff’s Complete Songs, Indiana University Press, 2014)

Listening to Petrova isn’t a mere exercise in passive hearing but an active experience of the visceral power of the human voice, of skill expressed with quiet confidence. Indeed, David Patrick Stearns’ observation in Gramophone that “when she sings of ‘magic stillness’ in ‘A Dream’, you hear it in her voice” applies far past the album’s track.

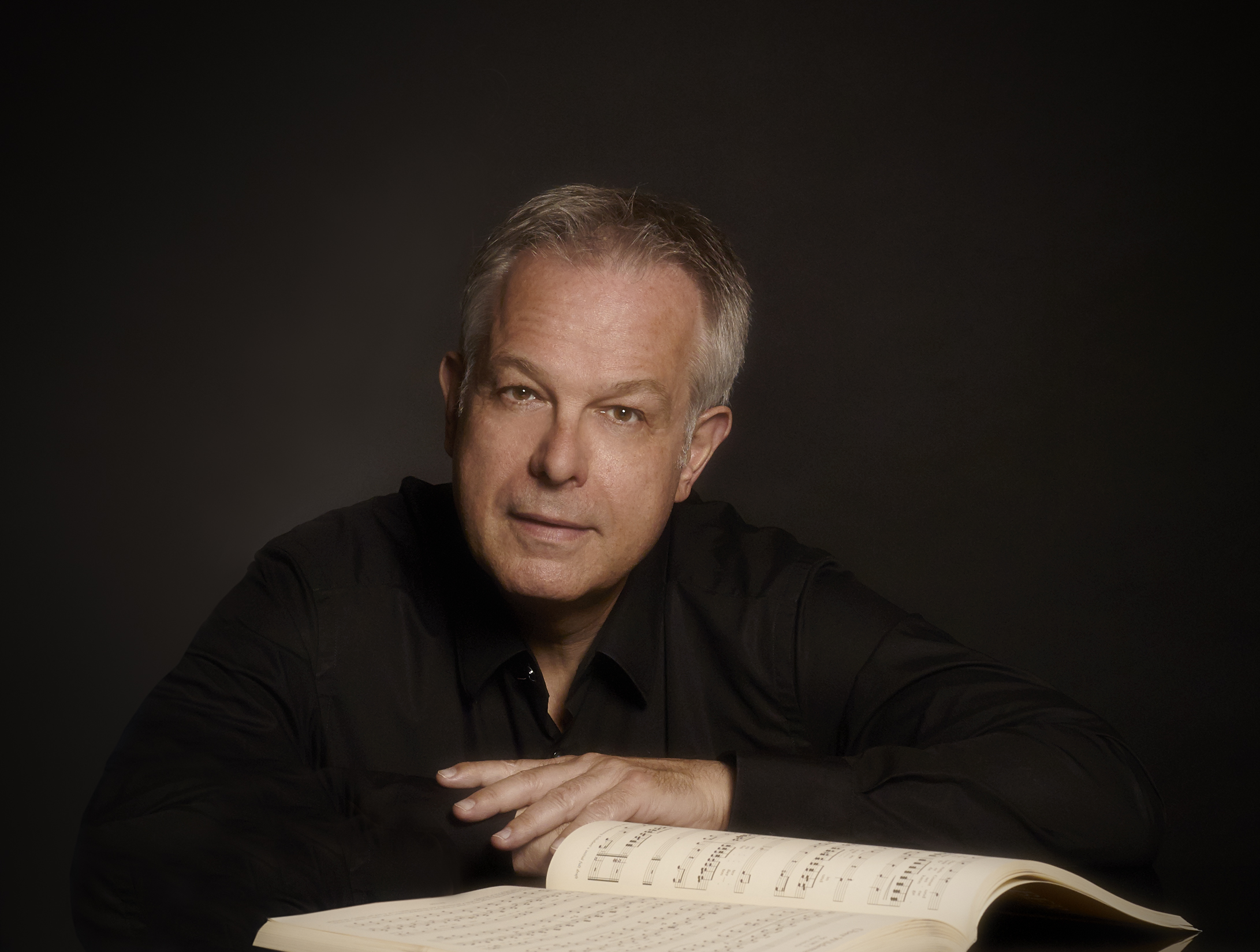

Petrova is currently preparing for her premiere performance of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, happening at Moscow’s Zardadye Concert Hall on February 22, with Tchaikovsky’s own “Ode To Joy” Cantata also on the bill. Vladimir Fedoseyev conducts the Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra together with the Prague Philharmonic Choir and chorus master Lukáš Vasilek, together with fellow soloists Daria Khozieva (mezzo-soprano) Vladimir Dmitruk (tenor) and Nikolay Didenko (bass). A more intimate appearance takes place at Zaryadye (in the small hall) on March 6, when Petrova will be giving a recital with pianist Rem Urasin. Together, the appearances encapsulate Petrova’s refusal to be easily classified or boxed in by sounds or experiences. We spoke recently when the soprano was recently back in Russia and busily preparing for her upcoming Zaryadye performances.

How did you choose the songs on your album?

I went through the whole of two Tchaikovsky volumes of song, and one big book of Rachmaninoff songs. I went through all of them, and chose what I liked, basically. Vladimir (Feltsman) also had ideas of what he wanted or not to do but mainly he left it all to me, and it was very special. Most of the songs I’ve never sung before, so it was very risky, I have to to say. We have a funny saying in Russian; we say, “the first blin” – blin is like a Russian pancake – “always goes badly” – but I don’t think it’s the case here, so I’m happy!

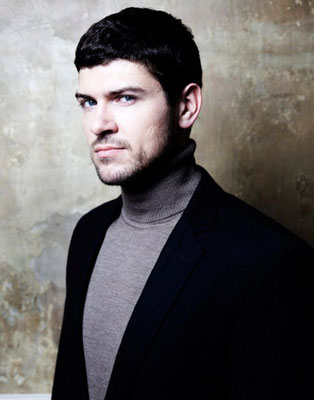

Photo: Vladimir Feltsman / Nimbus Records

I feel like your interpretations offer understanding on a deeper level that goes past language.

It’s like souls talking – mine, Vladimir’s and every person who listens. And it’s very universal. That’s the key to music: it communicates beyond words, heart to heart.

So are some of these going to be part of your recital in March at Zaryadye Hall?

Yes, most definitely, and with another phenomenal pianist, Rem Urasin.

Many singers I’ve spoken with emphasize the importance of doing recitals. What does that experience give you creatively?

It’s very true; recitals give a completely different connection with music, and a different connection with the audience, actually. The songs are rather short so you have to create a whole world in two to seven minutes, and it has to be the story, the complete story, so one recital in two sections gives us ten to twelve different worlds in each half, twenty to twenty-four songs all together – so basically I create twenty-four different worlds in one evening. And then I also love how it’s me, and the pianist, who is part of me – we are together; I always try to become one person with the pianist, and the audience. On stage we are very exposed, much more than in opera where we have costumes and sets and a director; it’s a completely different interaction. In recitals, I’m basically just sharing who I am and what I’ve learned; it’s much more intimate and in a way we are completely naked.

When you emerge on the other side, what things do you take back into the world of opera?

Absolutely I come out different. I know myself much better through this experience, as a musician and a person; I can create more defined characters and go, on a much, much deep level, into the characters I play onstage. I love drama, and I love theatre, and I love opera. I’m a singing actress, no questions asked – but I started to feel suffocated without doing recitals, without those little songs. I missed not sharing that side of me with people, and not having that experience. So I’m happy I am able to sing more songs nowadays.

And you’re doing your first performance of Beethoven’s 9th soon. His vocal writing is known for being difficult; what’s your experience as someone new to singing his music?

You know, as short as (the vocal part in Symphony No. 9) is – compared to any opera it’s very short – I have to agree, it’s difficult and rather demanding, and from a soprano point of view, it’s very high; he keeps the vocal line up there and we have to soar above the orchestra, and yet keep it graceful and also be “full of joy! full of joy!” but I’m very excited and am working hard on it. But of course I don’t want anybody to hear “Oh, she’s working hard!” when I perform it!

Sir Antonio Pappano once noted that Beethoven’s writing for voice is entirely analogous to his instrumental writing, minus the consideration that people actually have to breathe.

Yes, I know what he means! Basically you use everything you’ve ever gathered as an artist, and try to enjoy it and pray it comes out well! There are some brilliant moments – it’s phenomenal music.

With Matthew Rose (L) and Brindley Sherratt (R) in the 2018 London Philharmonic Orchestra presentation of Das Rheingold. Photo: Simon Jay Price

You’ve done Wagner too, which is also demanding vocally, though in an entirely different way.

Yes – I’m starting to do Wagner, and I have to say … it’s, well, Wagner is a genius but only when I started singing his music did I really embrace it, and now I’m feeling , like, “Wow, what a phenomenal experience for any musician to sing his music!” There’s a lot to discover in his work, it’s true – but I was surprised. I surprised myself at how much I love it.

It’s not music that is commonly done in Russia either.

Not that much, only in St. Petersburg – it’s done almost exclusively there. A few pieces are performed here and there, outside, but not really. I have to say it’s a whole universe, and I’m excited about becoming a part of it.

There’s no end of learning when it comes to Wagner’s work.

That’s true. It goes with my whole philosophy about singing, and the stage, and my profession: I never stop learning! Since I started singing, it’s always, to my mind, been a process of education. I am always learning something new, and always trying to make my instrument better. I am constantly finding new ways (of approach material) and new colours. It’s non-stop. So Wagner fits in perfectly in with how I see myself as a singer and my job.

You’re featured on The Compassion Project (Innova, 2018) as well – your work on the album features some new sounds for you, writing which I think suits you well vocally. What does performing contemporary work give you artistically?

I am searching for the not-well-known stuff, for things forgotten or for things fallen out of the limelight. I think it’s exciting for us as musicians to find those gems and open them and bring them to people. On our album with Feltsman there’s also some pieces of Tchaikovsky, ones few ever knew of – and it’s Tchaikovsky, of all people! It’s the same with contemporary music, but you see, it’s, how can I say, it’s challenging most of the time for singers if they don’t have a musical background, because you need to have a very attuned ear. You have to hear, really well, the intervals and all of the changes in harmony (within the composition) – it’s just a skill. As long as a young singer is willing to learn and challenge him or herself, they’ll find it exciting and fascinating, but if they are not secure enough, then of course it’s easier to stay with Mozart, because it’s universally harmonic and easy and something they’ll hear again and again.

… and it’s something audiences will have heard a lot as well. There’s something to be said for classical artists purposely – and purposefully – doing things outside the mainstream, on mainstream stages.

Yes, and I have say unfortunately it’s not that easy, because some people who organize concerts and programming at concert halls – not all but some – are afraid of new pieces, even if it’s not contemporary music. Recently I did a beautiful cycle by Bartók; it’s not contemporary – I mean, it isn’t Mozart but it’s not contemporary – but it’s glorious music, and I had to push for it. I had to use my name and all that, to just say, “Hey , don’t ignore this just because people haven’t heard it!” And later (audience members) came up and said, “That was phenomenal – thank you for introducing that to me!” People who organize for venues are scared, I guess because there are problems with financing – maybe difficulties related to the financial end of things – but hopefully again, if we keep doing what we love and what we feel is important, then we will push through these tough times.

It’s a chicken-and-egg situation.

Yes.

As Contessa Almaviva in the _ production of Le nozze di Figaro at Florida Grand Opera. Photo: Chris Kakol

Classical organizations in North America are facing similar issues, if in a more concentrated way. For instance, if Stravinsky is programmed, it’s always The Rite Of Spring, which is considered daring; it’s never lesser-known works that are just as interesting, if not more so. Organizations are scared tickets won’t move, but if you never program it, people won’t know, and they won’t have a chance to decide for themselves.

Thank you very much, yes!! But also for a musician it takes time and experience to have grown into that. For me, I feel now I have something special and unique to say in those new pieces, I feel I’ve grown in music and into the music and have learned enough in order to do it. So I can offer my vision and feel of it, and I hope people will love it, because it’s something new, something very personal and human. But again, it is constant work, and it all depends on if we’re willing to work and make ourselves better, and if we’re willing to push other things, and make concerted, constant pushes toward… what’s the word…

Evolution?

That’s a good one, yes. Never stopping. Trying new things will always teach you something!

Evolution is two-pronged; it’s work, as you said to do this – evolving is work– but it’s also allowing yourself to evolve, which means being open to all sorts of things, including discomfort, which takes courage to face. How much did your time with mezzo-soprano Elena Obraztsova helped to cultivate that quality?

She has always been one of those people I look up to, and the fact that I had a chance to meet her personally and a chance to share the stage with her… it’s huge! Also the trust she put in me and, you know, she was such a generous and kind person, and the things she told me when I was still young gave me so much confidence, you know what I mean? She believed in me so much, and that belief gave me wings, like, “Go baby, fly! Enjoy the singing and share with the people your gift!” Such an amazing woman and amazing artist she was, and I feel very fortunate and very blessed she was in my life, she IS in my life. I have, as we say, a ticket and a blessing from her for this career, and for this world of singing.

How much did she help to instil your sense of exploration?

It’s just how she was herself; Elena was never afraid to take a risk. For example, at some point she went into theatre; she was doing a lot of things with various organizations – recitals and working with contemporary composers, and being onstage doing big opera things and going to recital halls and doing small pieces – and when she was older she went into theatre, and people said “Are you crazy? What are you doing?!” And she was brilliant! But the main thing is she enjoyed it, and that was one of the biggest inspirations. (Obratzsova was artistic director of the Opera Company of St. Petersburg’s Mikhailovsky Theatre from 2007-2008, and appeared as The Countess in their production of Tchaikovsky’s The Queen Of Spades in 2011, the same year she created a charitable foundation to promote music education; she passed away in 2015.)

There are so many languages an artist can speak in terms of different ways and different approaches, and (Obratzsova) showed all of us there is never one way, that we don’t have to lock ourselves in one box: “I’m doing opera” or “I’m a recitalist” or whatever. She was free herself, and she inspired us in that way, those who were her students or the winners of her competition. She never put any chains on anybody; she never put anyone in a box. And that was a very big inspiration, no question.

That’s how it seems with you, that you’re not in a box of doing one style or sound, which reflects your life between the United States and Russia.

I feel like it’s a blessing and a gift; every way is different. Everybody has a right to choose the way they’re living and approach careers, and I love it. It’s very challenging, that’s true, but I do love it and I am trying to enjoy every minute of it. When I sing Wagner that doesn’t mean I don’t love singing Handel, or that I can’t; if I sing Handel that doesn’t mean I can’t sing my heart out in other modern pieces, or do the most intimate, almost whispering things in a recital. I love it all.