Is opera misunderstood?

When asked this question in 2007, British director Graham Vick said, “Yes, in that people believe they need to be educated about opera to understand it. Those who respond to it viscerally and emotionally are the ones who understand it best.”

This is something that I deeply relate to, having grown up with, and been raised by, a woman who, though not super educated about opera, responded in highly visceral, emotional ways to what she heard, so much so that on Saturday afternoons she’d stand in the middle of aisles at the local supermarket, radio earphones tilted back and nearly falling off her head, her mouth hanging open, her palms up, listening to live broadcasts from the Met, as fellow shoppers shot her dirty looks and angled their carts around her. As a teenager, I was mortified; as an adult, I understand, even if I don’t emulate my mother’s grocery store habits. (Yet.)

Vick is a director known for his experimental approach. People have strong opinions about his work; some love and whole-heartedly applaud it, others think it’s overwrought, silly, dumbed-down. While I’ve not seen any of his work live (that will change soon, I hope), I think Vick is one of those people who considers himself something of an ambassador for the art form. His ideas around the lack of empathy in modern society, the importance of involving various communities, and visceral reactions to culture ring big bells with me and the things I believe in terms of the power of art and music.

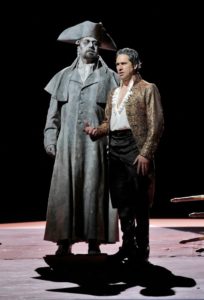

|

| Andrea Silvestrelli as the Commendatore and Ildebrando D’Arcangelo as Don Giovanni. Photo: Cory Weaver / San Francisco Opera |

One of the most powerful of all opera experiences for me is Don Giovanni. The opera is, as many of my regular readers may note, something of a favorite; it is also, to return to my first question, one of the more misunderstood works in the operatic repertoire. Some productions I’ve seen I have outright despised; others I found entertaining (like Komische Oper’s zany, Herbert Fritsch-directed production), while yet others made me re-think the opera entirely, illuminating its female characters and challenging perceptions of its main character. So much of what I think powers Mozart’s great opera is, in fact, the attitudes we, as audiences, bring into the auditorium; like any great work of art, our own experiences (and social conditioning) color what we experience, but when it comes to Giovanni especially, these attitudes show themselves in some very revealing ways, expressed mainly as our reactions to Donna Anna, Donna Elvira, Zerlina, and of course, to the Don himself.

Lately Don Giovanni has been frequently produced, what with the remount of Robert Carsen’s celebrated 2011 production on La Scala with baritone Thomas Hampson (one of the noted interpreters of the role) and bass baritone Luca Pisaroni (whose performance as Leporello I so enjoyed in Salzburg last summer); Opera in Holland Park and Opera Lausanne also celebrated their respective openings over the weekend, Gran Teatre Liceu (Barcelona) has a production opening later this month, and Festival d’Aix-en-Provence has a production next month. Don Giovanni is on now through June 30th at San Francisco Opera as part of their Summer of Love program.What is it about this work that so continues to entrance and excite artists and audiences alike? Why does the story of an unrepentant Lothario and the various women he loves and men he angers (and murders) — all within the space of one day — continue to have a grip on popular imagination? How does the work (and its telling) change through time, and why?

When I heard director Jacopo Spirei was helming a remount of a 2011 San Francisco Opera production originally directed by fellow Italian Gabriele Lavia, I was immediately intrigued. Spirei has an impressive resume of directing work, mainly focused in Europe and the UK; he got his start working with Graham Vick, and I’ve been following his career closely the last little while. Having already directed the opera two times prior to this (including at Salzburg’s renowned Landestheater), Spirei comes by his theatrical approach honestly. He spent considerable time in his twenties in England, seeing a variety of dramatic and operatic works at the English National Opera, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and the National Theatre. Eventually he went on to work with Vick at the celebrated Glyndebourne Festival. Spirei has since directed works at the Wexford Festival in Ireland, the Royal Danish Opera, Houston Grand Opera, the Theater an der Wien (Vienna), and Teatro Comunale di Bologna, among many others. Later this year he’ll be directing the opera Falstaff (based on Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor as well as scenes from Henry IV, parts 1 and 2) at the famous Festival Verdi in Parma, Italy.

|

| Director Jacopo Spirei. Photo: Mary Marshania |

In making his debut with the San Francisco Opera, Spirei had to take the work of another director, in a production from six years ago, and make it his own. In addition to wondering what that must’ve been like, I was also curious to learn his thoughts about various characters (especially the female ones) in the opera, and what it’s been like to work with artists who come with lots of prior experience in the role. Our conversation was very wide-ranging and, at times, quite intense, if equally friendly, and very lively. Spirei definitely has his opinions, but he has what I’d call the iron-hand-in-velvet-glove approach; he doesn’t hit you over the head with ideas or proclaim decrees, but rather, contextualizes artistic and musical history, with some fun contemporary corollaries, to make truly interesting suggestions. You don’t have to agree with what he says, of course, but it’s worth ruminating on, at the very least. As I wrote in a past feature, sometimes it’s nice to be presented with new ideas on something you thought you knew very well, even if, initially, it’s a bit uncomfortable.

Owing to the wide nature of our conversation, I’ve divided our chat into two sections; expect Part 2 soon. We discuss the role of so-called “tradition” in opera, bringing the art form out of the theater, and what he meant when he recently told Newsweek that “In Italy, (opera) is all about putting on a pretty picture.” For now, here’s Spirei on Don Giovanni.

What’s it like as a director to come to a production that already exists, and to try to put your own stamp on it?I’ve never done anything like this, but it’s been fascinating, to get, somehow, the limited set of ingredients and just create a new dish, because it’s a little bit of, when you have boundaries you are forced to be a lot more creative. Sometimes the boundaries are budget, artists, all kinds of different aspects, which is incredibly fascinating and exciting. This was the real challenge, to reinvent an element already there, although the starting point (of the original) is something that intrigued me a lot.

What was the element?

The fact the mirrors were central in the original production. I find it really attractive in a way, how Giovanni is a mirror to the other characters, showing us their real sides, taking everything from them. Somehow we’ve stripped everything away, so it’s just the element and dynamic in which the characters interact with each other and Giovanni.

You’re working with people who have a lot of experience with this work, and this character.

It’s great; it’s luxury. People come with their own luggage of experience of contributions. We’ve been working in an incredibly organic way — with (conductor) Marc (Minkowski), with Ildebrando (D’Arcangelo, who sings the lead) it’s been a great time of sharing and experiencing new material and finding new angles.

What I enjoy about working with Ildebrando is that he’s an artist who comes with a lot of experience, and a lot of expertise and knowledge, but he’s completely willing to try out new things and put himself in your hands, to experiment. It’s been really exciting to have worked someone who has been so fun. We didn’t have to do all the preliminary work; we both know the material really well, so basically a glance of the eye is enough for both of us to understand which way we’re going. It’s something I’ve never experienced in my life; with a look, he understands what you’re thinking and you can communicate with him in the same way, and then steer his performance into different directions. I’ve enjoyed that immensely.

Marc is the same. I love his approach to the tempi; it’s very refreshing, (in that) it’s very new, very contemporary, especially coming from period music. He’s an expert in that, of course — Baroque and ancient music — but he brings that freshness that conductors who come from that repertoire have. This is really exciting.

In many ways Don Giovanni feels like it belongs in the 21st century; it has so much to say about humans and relationships.

Absolutely. I’ve done Giovanni three times, in three completely different settings, time-wise, period-wise, visually as well. It’s extraordinary how much Giovanni has to give. You never get to the bottom of it. One could work on this opera forever and never get tired, though you might become obsessed, and be haunted by it! It’s a phenomenal piece to study, and like every Mozart piece, it never ceases to make us understand ourselves and the times in which we live. Giovanni is the man who is not willing to pay a price for his actions, who is completely free and without boundaries, with no morals, who pushes forward and never looks back.

|

| Erwin Schrott as Leporello and Ildebrando D’Arcangelo as Don Giovanni. Photo: Cory Weaver / San Francisco Opera |

What you’re saying makes me wonder, is he a symbol more than an actual man?

Yes of course, absolutely.

I’ve spoken with others who insist he is, and has to be, the latter.

Not at all! The thing is, that, if anything he is an example. What he is, is not Casanova, who is an historical figure; he’s a legend, a legendary character, and in a way, he has gone through five centuries of theater and has transformed himself every time because every century has looked at this character through their own lenses. The 18th century viewed him as a man who gets punished because he doesn’t take responsibility for his actions and follows instincts; it’s not a positive example.

The 19th century adored the element of him being against everything — but “Viva la libertà” is not a hail to freedom, it’s a hail to liberty, to do whatever you want. That’s not an altogether positive value, it’s the freedom to do whatever you like, however it pleases you, no matter what consequences it has on other people, which is the boundary of freedom. As you say, my liberty finishes when yours begins; Giovanni has none of (the awareness of consequences), so of course we’re fascinated and attracted, like we’re attracted to an abyss, or a tornado.

I feel like the women really define him in many ways in this opera; they’re all incredibly important.

In the story, that day in the life of Giovanni, he doesn’t even seduce anybody! The only woman who’s in love with him is one who was abandoned from another place and is chasing him. We know he has a lot of women only by the words of Leporello about the catalogue, which is a list he makes as he says, but… is it a collection? Are those numbers real? The great thing about Giovanni is deceit; he’s constantly deceiving us as much as he’s deceiving everyone else. With Anna of course, there are lots of different approaches to that (situation), but it starts with the rape…

… if you want to call it that; some directors think it’s questionable if that’s what it actually is; I’ve come to think it is, too.

It is questionable, but once you go through the music and what she says, and the dramatic tension of the music, the trauma is there. Had she not shouted, her father would have not turned up — her father (the Commendatore) would be alive; if she shut up and didn’t do anything and let Giovanni go ahead and do whatever he was doing, her father would still be alive. She does carry that guilt, no matter how conscientious or not-conscientious she is. That’s one element. Another is that Zerlina is seduced by the money; she says “yes!” the minute he tells her, “I have a villa and will marry you.”

You can’t forget positions in this opera; he is called “Don” for a reason, after all.

Absolutely.

I get frustrated with stagings that forget that part, and ones in which the women are victimized.

What’s fascinating is the characters also change. Elvira is a victim of Leporello and the catalogue aria, and we laugh at her until she tells us, “My God, he has betrayed me with so many women” and all of a sudden, we are with her in that pain. It’s the same moment when we find out our partners had betrayed and cheated on us. It’s so incredibly raw and so close to ourselves. One cannot simplify it into victims and non-victims; each one is a character representing an element of our personality.

… while also being a real human being: complex and nuanced.

Absolutely.

___

Here’s Part Two of our chat, in which we discuss the role of theater in a broader sense, the debate on tradition in opera presentation, and opera fashion (To dress up or not to dress up?). Enjoy!