Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Against the odds – or perhaps because of them – opera is making a welcome in some parts of Europe. Boris Godunov runs at Opernhaus Zürich September 20th through October 20th for six performances only, with baritone Michael Volle making his role debut as the titular czar. The production, directed by Barrie Kosky and conducted by Kiril Karabits, also features bass Brindley Sherratt as the thoughtful monk Pimen and tenor John Daszak as calculating advisor Shuisky. The project is unusual for not only its unique presentation (singers in house; orchestra and chorus down the street) but for the fact it’s happening at all; at a time when live performance is being set firmly to the side, the production of an opera – any opera, but particularly one as demanding as Mussorgsky’s 1874 opera, based on Pushkin’s (written in 1825 but only presented in 1866), produced here with the immense Polish scene – feels like a strong statement for the centrality of live classical music presentation within the greater quilt of life and the good, full, thoughtful and varied living of it. In the era of the coronavirus pandemic, opera is not, as Opernhaus Zürich and others across continental Europe seem to imply, a gold-threaded frill but a sturdily-sewn hem, one comprised of the common threads of community, communication, and not least, creativity.

Thus is Opernhaus Zürich’s current production of Boris Godunov making history, particularly in an industry hard hit by a steady stream of COVID19 cancellations. It’s true that creative operatic presentation (particularly the outdoor variety) is leading the way for the return of live performance (as an article in The Guardian suggests), but the price for freelance artists has, nevertheless, been totally devastating, and many musicians are leaving (or considering leaving) the industry altogether. The cost of singing, as Opera expertly outlined recently, is immense, and in the era of COVID, there simply isn’t the work to justify such expenditure. Amidst such grimness Boris feels like a blessing, fulfilling those needs for community, communication, and creativity, needs which so often drive, sustain, and develop great artists. Two singers involved in the Zürich production, Sherratt and Daszak, are themselves freelancers and, like many, lost numerous gigs last season, a trend which is unfortunately extending into the current one. As British singers working abroad (Daszak is based in Sweden), both men have varied if similar experiences appearing in memorable stagings that highlight acting talents as equally as respective vocal gifts. Sherratt’s resume includes an affectingly creepy, highly disturbing performance as Arkel in director Dmitri Tcherniakov’s staging of Pelleas et Melisande at Opernhaus Zürich in 2016. Daszak appeared at the house in 2018 in Barrie Kosky’s production of Die Gezeichneten; his Alviano Salvago plumbing layers of hurt, shame, and a visceral, deep-rooted despair.

Both performers have, like so very many of their cohorts, experienced tidal waves of cancellations for the better part of 2020. Sherratt had been preparing his first Pimen back in March with Bayerische Staatsoper; Daszak was in Vienna rehearsing Agrippa/Mephistopheles in The Fiery Angel. Both projects were cancelled at the outset of the pandemic, along with subsequent work at Festival D’Aix en Provence, Staatsoper Unter den Linden (Berlin), and The Met, respectively. The revival of the 2016 opera South Pole in which Daszak was set to sing the role of Robert Falcon Scott (the Royal Navy officer who led various missions to Antarctica), has been cancelled; its creative requirements contravene existing safety regulations in Bavaria, as Daszak explained in our recent chat; the work was have to run in November and was to have also featured baritone Thomas Hampson as Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. Daszak’s plans for New York are also off; he was to perform in the revival of Richard Jones’ production of Hansel & Gretel, as The Witch, this autumn. Sherratt’s workload this season has been equally hit; the long-planned presentations of Wagner’s Ring Cycle by the London Philharmonic Orchestra in January-February 2021, in which Sherratt was to appear as Hundig (in Die Walküre) and Hagen (Götterdämmerung), have been called off, LPO Chief Executive David Burke explaining that costs, combined with an uncertain climate characterized by ever-shifting regulations, make the highly-anticipated work impossible to realize.

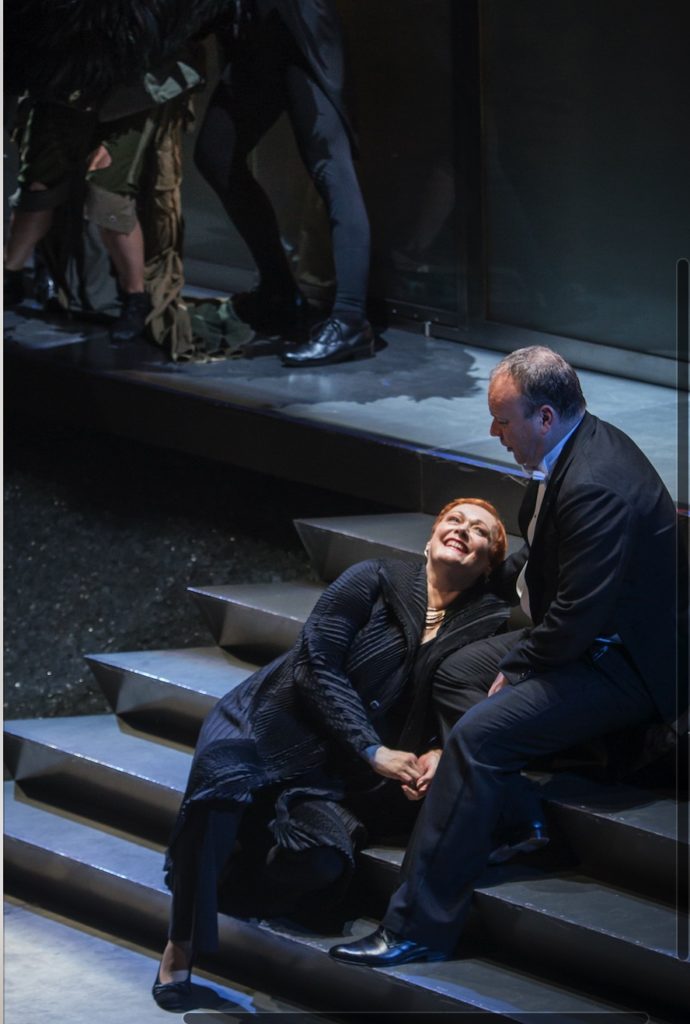

John Daszak as Schuiski in Boris Godunov at Opernhaus Zürich. Photo: Monika Rittershaus

The elasticity of Kosky’s creative approach and Opernhaus Zürich’s willingness (and budget) to allow such experimentation has allowed for ideas to be grown and cultivated entirely out of existing health protocols; as a result, the orchestra and chorus will be, for the duration of the run, performing live from the Opernhaus’s rehearsal studios a short distance away from the actual house, with their audio transferred live into the auditorium thanks to sophisticated and very meticulous sound engineering. Opera purists might sneer that it isn’t real opera at all without a live orchestra and chorus, particularly for a work that so heavily relies on both for its dramatic heft, but the artists, far from being adversely affected, seem to have energetically absorbed a certain amount of zest from such an audacious approach. While some may perceive a “return to normal” in rather opulent terms, Kosky’s approach underlines the need for opera creators and audiences to embrace more creative theatrical possibilities and practises, ones whose realization has been, for some, long overdue. In Pushkin’s play, Shuisky remarks that “tis not the time for recollection. There are times when I should counsel you not to remember, but even to forget.” Godunov himself cannot forget of course, but the era of COVID19 has inspired sharply contrasting reactions; a cultural amnesia in some spheres, with the willful neglect of the role of the arts in elevating discourse and inspiring much-needed reflection, together with a deep-seated longing for a comforting familiarity attached to decadent live presentation, an intransigent form of nostalgia adhering to the very cliches which render live presentation in such a guise impossible. Is our current pandemic era asking (and in some places, demanding) that we entirely forget the gold buttons and velvet tunics, the gilded crowns and towering headresses, the hooped skirts and high wigs? How opera will look, what audiences want, and how those possibilities and desires may change, are ever-evolving questions, ones currently being explored in a variety of settings (indoor and outdoor), within a willfully live – and notably not digital-only – context; that willfulness, as you will read, is something both Sherratt and Daszak strongly believe needs to exist in order for culture, especially now, to flourish. Is there room for surprise and discovery amidst fear and uncertainty? Where there’s a will, there may very well be a way.

This will which is manifest in the realization of Boris Godunov in Zürich has its own merits and related costs both tangible and not, but the production’s lack of a live chorus is not, in fact, a wholly new phenomenon. The physical presence of the chorus has not always been observed in various presentations of Boris Godunov; at London’s Southbank Centre in early 2015 for instance, conductor and frequent Kosky collaborator Vladimir Jurowski, together with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, presented three scenes from work with a chorus recorded during prior OAE performances at St. Petersburg’s Mikhailovsky Theatre. Kosky himself, as you’ll read, joked before rehearsals began about this onstage presence, or lack thereof. As both Sherratt and Daszak noted during our conversation, the level of quality in Zürich renders a sonic immediacy which, even for artists so used to live interaction, is startling; the actual lack of physical presence of what is by many considered the central “character” of Godunov as an actual dramatic device holds an extraordinary meaning in the age of social distancing and government-mandated quarantine. An extra layer of meta-theatrical experience will be added, consciously or not, with the production’s online broadcast on September 26th, a date neither singer seemed particularly nervous about – rather, there is a real sense of joy, in this, and understandably, in getting back to work. Our lively, vivid chat took place during rehearsals, with the bass and tenor discussing staging and music as well as the politics of culture and the role of education, which seems to be more pertinent than ever within the classical music realm. Of course the intercontinental divides in attitudes to culture can be distilled into financial realities (funding for the arts is higher in some places than others) but within that framework lies the foundational experience of exposure, education, and awareness – and, as Sherratt rightly point out there, the will to make things happen in the first place.

Barrie Kosky’s production of Boris Godunov at Opernhaus Zürich, 2020. Photo: Monika Rittershaus

How are rehearsals going?

JD Good! It’s surprising when I think, considering we have no chorus onstage and no orchestra in the pit, at how it’s going particularly well – they’re a kilometre away, up the road in another building. The sound is being piped in by fiber optic cable. We were worried things could go wrong but generally they’re getting on top of it. It was good today wasn’t it, Brin?

BS It’s amazing. All these monitors and speakers are in the pit pretty much, so it sounds like the orchestra is down there.

JD And actually they have so many different speakers and microphones and they all sound directional, like different sounds in different areas of the pit… it’s quite incredible.

When I spoke to Barrie earlier this summer he referenced this production a few times – it sounds as if you don’t have a problem with the way it’s been organized with the orchestra, or… ?

JD It’s a problem in that it’s not the same sound we’re used to; they’re playing live but it’s almost impossible to replicate an exact sound, no matter how much they spend on the system to replicate that live sound. We’re worried about balance because a sound guy is controlling the volume and at times they need to increase the chorus to sound more present onstage, but they have enough time to work on it.

BS It was dicey at the start, but it’s getting better all the time. Kiril (Karabits) is with the orchestra and looking at a monitor of us on the stage, and where the conductor should be is a monitor, so we watch the monitor as we do for other monitors normally, and the orchestra also have these screens and they can see what’s happening on the stage. It’s not as if the conductor was there he would see it all as big as life; he has a limited view of the hall to look at. If anything I think his job is the most difficult because he doesn’t have that direct contact with the stage all conductors are used to having.

Is it challenging as a singer to not have that live energetic exchange with a conductor?

JD We were concerned about that, all of us – we didn’t know what it would be like. I remember in Royal Albert Hall years ago, when they’d do opera in there, and the orchestra was behind you so you had to watch the monitors, but the conductor was at least there, live. Here he’s not in the same building, and we were concerned about that, but we had a lot of rehearsal with him before we got to the stage; we’ve had three, almost four weeks in the studio before we came to the stage, and then rehearsals onstage with him live in the pit. Normally by that point a conductor is pretty used to what we’ll do and we’re used to doing what he wants, and that’s the case here too, so won’t be too problematic for us – moreso for him, especially if something goes wrong onstage. He has to be very attentive to that.

It must be a nice feeling to be back on stage – the last time was in Vienna for you, John?

JD Yes that’s right. We started rehearsals in March – we got two weeks into The Fiery Angel but then the shit hit the fan and we were all sent home. That was my last live performance, apart from a couple concerts at home in Sweden, which weren’t professional in the same way. It’s nice to get back onstage.

Brindley Sherratt as Pimen in Boris Godunov in Zürich. Photo: Monika Rittershaus

Brindley, you were about to rehearse another Boris Godunov (directed by Calixto Bieito) in Munich before it was cancelled, yes?

BS In fact they called me an hour before the first rehearsal to say, “Don’t bother coming in” – I’d arrived the night before. The last time I was on the stage in a fully-staged opera was November of last year in New York, so it’s been ten months really, and now, getting back, it feels like normal – I slipped into the rhythm of it and got used to singing in an opera and all that goes with it, and it feels like normal; I’d almost forgotten. It’s a desert everywhere else.

JD I felt like a criminal getting on the airplane to come here.

BS I feel here in Zürich, even now, they’ve clamped down a bit. You have to wear a mask on public transport and in the shops but there isn’t the same atmosphere of fear as in the UK, of doing this dance to avoid people – there isn’t that, generally speaking, they’re more relaxed I would say – but like John, I felt when I was about to get on the Eurotunnel in my car, a little bit of survivor’s guilt. Because you want to tell everybody that “I’m going to work! I’m going to do an opera in the theatre!” – you want to tell them it’s going to happen in places where they are courageous and able to fund things and you want to shout, “Opera’s not dead!” – but at the same time you are aware that a lot of your colleagues are out of work.

JD I’ve had mixed responses – a lot of people say, “We want to hear how it goes, because it gives us hope, every little bit of things turning back on is good to see, because it means it’s coming back together.” I just had another run of performances cancelled in Munich in November – I’m doing the Wozzeck coming up, but was also going to do South Pole but they’ve had to cancel it because they can’t fit the orchestra – which is a big orchestra with lots of technical things they need to sort out – they just can’t fit it in the pit safely… and Munich is a massive house. Seriously, you have to have vision; I think Zürich is very brave doing this. A lot of people could say, “Well this isn’t really live opera!” but it is; we’re all playing together, we’re just not in the same building. I think they’re very courageous to do this. It means they can now open, and they’re running their normal season. It will take a while to get back to real normality but I think it’s a really good idea and it seems to be working.

BS Obviously we kind of hope this will be paving the way, or pioneering the way, cutting the through the jungle, that people will come and say, “Maybe we can do something this way, with social distancing” – there’s a chorus of fifty and an orchestra of eighty that are in a room somewhere else, and that can be done in lots of spaces. A lot of ideas can spring from that sort of arrangement.

JD It’s not an ideal situation…

BS… but it’s something.

JD … yes, it’s a great thing to start with. We need to see live performances in theatres; as soloists, we are giving as much as we can onstage, and I think I’ll be an operatic experience. It’s just not going to be a comparatively normal operatic experience, but for a start, I think it’s a great solution.

Michael Volle (L) as Boris Godunov and John Daszak (R) as Shuisky in Boris Godunov at Opernhaus Zürich. Photo: Monika Rittershaus

How much do you see projects like this leading the way in the COVID era? I’m not sure this production of Boris would be accepted in some places, which have very specific ideas about how opera should look and sound.

JD I think there are big arguments… if you’re reliant on sponsorship, ticket sales, you’ve got to be more commercial or at least you’ve got to cater for what you think people want, rather than really cutting-edge art, in my view. I think the European system of public funding, especially in Germany, Spain, France, Italy if there is any money there, they’re not reliant on ticket sales so they can be far, far more adventurous, and that’s why I think there’s this tradition of pushing the borders, especially in Germany, with trying new ideas. I think it’s vital to experiment. There should be an allowance to to fail – I don’t see any problem with that. If a director wants something or a conductor wants and tries something, and we try to fulfill that for them, and it fails, so be it. It’s what we do as artists.

You won’t be performing in quite a full house, is that right?

JD The seating capacity in the theatre in Zürich now… I think we’re allowed 500 in one place and now 1000.

BS … which is great, it’s a small theatre anyway, but I think it’s more of an issue of countries and governments being comfortable with the audience being safe, not only the artists; that’s the main issue. Back in the UK they’re still allowing indoor performances so long as it’s socially distanced – and despite that, there is nothing happening in the West End. The health secretary dictated meetings of no more than six people and everybody went “WHAT?! We have stuff in the diary!” And the culture secretary sent a tweet out to clarify that that rule doesn’t apply to socially distanced performances; we can still have those. So I hope there is something happening soon.

To be involved in this Boris feels historic somehow… Do you feel the weight of that?

BS I don’t think we’ll forget it – not just because it’s one of the few contracts I’ve got left in the season, but because of the experience, the whole thing of working in this environment, it’s become more familiar now, like normal now, you just become aware quickly it isn’t the same.

JD We feel very lucky to be able to do this, to be one of the first to spring back to life. There is a guilt there as Brin said, but at the same time you are aware you’re giving hope to your colleagues. I’m pretty confident it will be successful, and we have the right guy at the helm. Barrie sent me a message before rehearsals started saying, “Hmmm, Boris Godunov without a chorus onstage: challenge of a lifetime!”

BS I always thought, if anybody can think out of the box, it’s Barrie. He could quickly come up with an idea, like, “Here, let’s do this” rather than, “OH MY GOD! MY PRECIOUS CREATION THAT TOOK YEARS OF PLANNING IS GONE!” It was, “Okay, let’s just do this, and see how it goes.” It’s thinking on your feet, thinking out of the box.

JD It’s been an inspiration to see and be around. I must say, when I heard our production of South Pole in Munich was getting cancelled, I said to my agent, “Surely they could do something like what’s being done in Zürich!” Bear in mind, the cost of the equipment is apparently astronomical. This quality of sound… when they started the overture yesterday, there’s a bassoon, and it sounded like it was in the pit… like a bassoon, right in the pit! Before, it sounded tinny, and they adjusted things and I think they’ll improve the sound with each performance. I think it’s millions they’ve spent…

BS It’s a lot of money.

JD … so it’s something to bear in mind, that not everyone can afford this kind of cutting-edge technology, but my gosh, it sounds almost like the orchestra is really there.

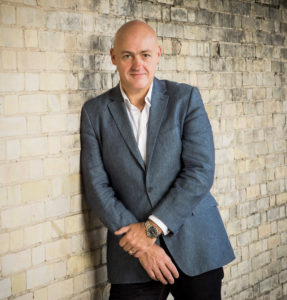

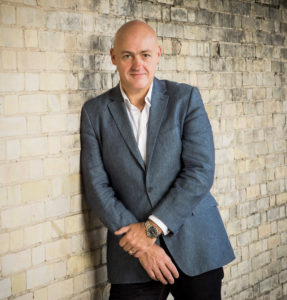

Photo: Gerard Collett

How much do you think this sense of immediacy is experienced by various audiences?

BS Well I went to a concert here recently and… I was staggered. It was pretty much a full house, we all had masks on but the orchestra on stage were as normal. At first, when the band started to tune up, I thought, my God… then they played some pieces which I love,and I welled up because it reminded me of when I was a trumpet player in the youth orchestra years ago. So I felt emotional anyway because of that, but it was the sound… that live sound, the sound of applause and cheers and laughter and people standing up and showing their pleasure, that was the most moving part. Chatting to people afterwards, I said what I’d been thinking, how elsewhere it’s a bit of desert. And the orchestra manager actually said, “Maybe also there isn’t the political will, or the will overall.“ And indeed, there isn’t this sense of, “We must have this back; it is vital to our society to have this back,” it’s “How soon can we get back to the pub, and the club, and have our football.” It’s a different emphasis. Sure, it’s the cash and government funding, but there’s also the actual will that we have to do something. The arts is much more highly prized here; culture is an essential part of life.

JD In Germany you go on the U-Bahn and you hear classical music being piped in down there…

BS … and in Vienna, on the subways on the walls, there are videos of various shows, and you walk down the road, I can’t remember the one, and on the pavement are all classical musicians.

JD The main problem over the years is that we’ve lost music education in schools. It’s just like having a language; if you are not brought up to learn Russian, how can you suddenly hear it and understand?

BS Bravo, John…

JD There’s no money in music education anymore, it’s dwindled over the last twenty-five or thirty years, and it’s the same all over the world now, but at different stages. Even in Germany there’s less and less support for the arts, really, and I think that leads to younger people growing up not understanding classical music, and thinking it’s somehow elitist. When I was a youngster there were choral societies all over Britain; we used to learn all the various songs and styles. If we don’t educate youth on these things, we’re in trouble, but of course, there’s no political weight in it.

BS There’s no political weight or will, and that’s the issue.

JD I heard years ago in the UK it’s science, maths, and technology, those are the things they were promoting and encouraging in schools, and for some reason they don’t see music and culture as important but as we said about Barrie, it’s about thinking outside the box. Theatre and music and drama are all about using your imagination, and I think it’s a really big problem to not have that ability to think outside the box, in any field. A Nobel Prize winner was once asked what his biggest influence was and he said, “My bassoon teacher.”

So how have you been keeping up your own training and education over the last few months?

BS I kept my voice going for fun, and learned some stuff for next year, and then I went on holiday for a couple weeks, then I came back and thought, “I better start singing Boris” – and my voice was just crap! The first few weeks felt dry and horrible. The last couple of days, it does feel a bit better; I don’t know if that’s the way I was singing or something, it was… being onstage again, you just find a way of going for it. I think a lot of it is mental – singing big, singing big music, singing in a theatre – you have to find something different amidst all of it …

JD I think it doesn’t matter what the music is – it can be difficult or not, but you have to make a beautiful sound. This (work) is far more conversational, I mean Brin has a much more challenging role than I do, Shuisky is not so much about vocal production, it’s quite a short role, an important one, but it’s more conversational and there’s more intrigue with the character, so for me it was not the same challenge. The weird thing is, I felt so far away from the business; I was surprised at that. I didn’t want to leave home – I’d been there for five months, which is odd for us opera people, who spend such long periods of time away. Suddenly you’re with the family and experiencing real life in a way you really don’t otherwise. When your life is frequently away from home you miss out on the normal life that most people experience. So it was great to have the opportunity to be there for a few birthdays and family gatherings, and to work on the garden for once; normally you go away and you come back two months later and everything is on the ground and you think, “I’m only here for three days, what will I do?!” It’s been amazing, growing things in the garden, going out on the boat fishing, seeing family a lot – it has been fantastic – but I have felt so far away from opera in some ways. Then with Boris it was, “Oh! I have to go back to work!’ and I put it off for a while thinking, “Ah, it’ll be cancelled” – that was the first thing; then a few weeks went by and my agent rang and said, “It’s definitely happening” and I looked at the music and was 120% working on it. Fortunately I’m not having to sing that extremely for this, but anything is hard when you’re out of it and have to come back. There’s also the mental pressure: you haven’t performed in such a long time, and suddenly you’re back with top-notch professionals, in a top-notch theatre, and you have to put it back on again! I remember Brin and I talking about it, this feeling of, “Oh gosh, we’re back to square one” but within two weeks, everything was back to normal, and it doesn’t feel any different. I didn’t expect that.

BS As John said, for a while you think, “So long as I have a nice meal and some nice wine and sing a little bit, honestly, it’s fine” but then suddenly, somebody says, “We need more of this and that sound” and you go, “Oh goodness, I forgot about this!”

JD Brin was a bit depressed to start with – he wasn’t himself. Pimen is a big role, it’s in Russian, it’s lots of work and memorization, but also it’s getting back into the business, and the character is rather depressive as well, so it was … kind of a mirror of what’s been going on in real life.

BS That’s the thing: mental fitness is an issue, not just vocally or physically, but mentally. I mean, last week I was amazed we did back-to-back stage piano rehearsals and I was really tired, physically tired; I’m just not used to it – I’m okay now, but was a bit scary! After this I have a contract to do some concerts in Madrid, but after that, I just lost two projects early next year – the LPO Ring won’t happen – and I don’t have anything in the calendar until March-April 2021, which is terrifying really. I am just getting going again.

So as you get going now, are you already thinking about the end of the run?

BS Oh for sure.

Photo: Robert Workman

How do you keep your focus?

JD Over the years you get thick-skinned with our business, because it’s pretty brutal from day one. You start off singing in college and go out and audition and don’t get jobs and someone says you’re terrible and someone else says you’re fantastic but doesn’t give you a job; the next year they offer you a job but you’re already booked… I mean, you get used to the whole spectrum of good and bad. So I think most singers are pretty thick-skinned and used to disappointment… but this is a very strange phenomenon; it’s abnormal for everyone in every walk of life. We’ve been hit badly but so have lots of people. It’s sunk in to accept it now;. I’ve had work cancelled – Munich and The Met’s been cancelled, it was supposed to be Hansel and Gretel (it’s a gift to play the witch!) and it’s just strange.

… which is why things like Boris Godunov seem so precious.

JD I’m pretty positive about the future, but not the immediate future.

B Not immediately – you have a contingency plan for say, three or four months, but not for the best part of a year. And no matter what you earn or what stage you’re at or what job you have, if someone says, “I’ll take away your income for the best part of a year, from tomorrow” – it’s a massive belly blow.

JD Nobody can prepare for that, really. We’ve not experienced something like this for a long, long time.

This era has really revealed the lack of understanding of the position of those who work in the arts.

JD There are massive overheads – people don’t realize that. I mean, I’m from a working class background in the north of England –there was nothing posh about my upbringing.

BS The same goes for me, I mean there are some singers who do come from privileged backgrounds but equally there are those of us who didn’t, at all; we had humble starts and had our introduction was through school teachers or family music, and that’s how we did it. The circles John and I are privileged to work in do have people who are quite well-heeled, but as far as the performers go, that isn’t the case at all.

JD The thing is, the more we take away from music education of young people, the more elite it will in fact become, because it’ll only be the rich people who can afford lessons and upper class families who know about it and were educated in that. It’s fighting a losing battle in some places. My wife sang for a few years, she was part of a group of three sopranos, and they sang at the Nobel Awards and had quite a big profile in Sweden, and they used to do things, going into schools, and allowing someone to hear operatic voices in a room; it’s amazing the effect that has, a properly-produced sound from a human body. And it was really shocking for some people to hear that. I think it’s important to be exposed to this music, to close your eyes and use your imagination – that’s what it’s all about; that’s why we’re in the theatre. It’s all about the power of imagination. We really have to remember that now.

Trippett and I spoke briefly after the 2018 performance, but unfortunately we didn’t have the kind of extended, chewy exchange I would have liked. Thank goodness for an email that landed in my inbox this past April from Europe-based classical writer Dejan Vukosavljevic, asking if I would be interested in just this exchange, one which he and Trippett, who is Professor of Music at Cambridge University, had happily conducted earlier this year. Vukosavljevic explores not only Liszt’s work but the complicated artist behind it, his very complex relationship with Wagner, the possibilities for a work long thought lost, and, more immediately, inquires as to how the pandemic impacted academic pursuits. Trippett himself is a formidable interview subject, knowledgeable but never stuffy, excited to share discoveries, his joy of the material (and their various social, cultural, political, and historical

Trippett and I spoke briefly after the 2018 performance, but unfortunately we didn’t have the kind of extended, chewy exchange I would have liked. Thank goodness for an email that landed in my inbox this past April from Europe-based classical writer Dejan Vukosavljevic, asking if I would be interested in just this exchange, one which he and Trippett, who is Professor of Music at Cambridge University, had happily conducted earlier this year. Vukosavljevic explores not only Liszt’s work but the complicated artist behind it, his very complex relationship with Wagner, the possibilities for a work long thought lost, and, more immediately, inquires as to how the pandemic impacted academic pursuits. Trippett himself is a formidable interview subject, knowledgeable but never stuffy, excited to share discoveries, his joy of the material (and their various social, cultural, political, and historical  DT: Originally I intended to do my doctoral research on Franz Liszt. I’d played so much of his piano music as a child that it had become a point of orientation for me, and I often felt it refracted in the music of others, from Debussy to Ligeti. In the end I defected to Wagner. I had listened to the Ring cycle three times when I was 14 (

DT: Originally I intended to do my doctoral research on Franz Liszt. I’d played so much of his piano music as a child that it had become a point of orientation for me, and I often felt it refracted in the music of others, from Debussy to Ligeti. In the end I defected to Wagner. I had listened to the Ring cycle three times when I was 14 (