Jan Lisiecki has had a busy summer. Performances at a number of celebrated summer festivals, including Schleswig-Holstein Musik-Festival (SHMF), the Rheingau Musik Festival, Klavier Festival Ruhr, and Musikfest Kreuth left the pianist little time to prepare for his release of a long-planned project, Frederic Chopin: Complete Nocturnes (Deutsche Grammophon) but in speaking recently from his home base in Calgary, Lisiecki is chatty and energetic, a keen conversationalist who clearly revels in the reciprocal exchange of artistic ideas.

It’s an approach that colors his latest release, one which, as he explains, had been in his mind to do for many years. Hardly his first foray into playing or recording the much-loved music of the Polish composer (he’s released recordings in 2013 and 2017, respectively), his approach to the nocturnes conveys a delicate musical sensibility and a keen artistic maturity which belie Lisiecki’s own relative youth (he is not yet 30 years of age) and, even amidst pandemic, kept him in a creatively aware state which greatly aided in the realized recording. Lisiecki’s fame as a sort of wunderkind of the keyboard through the last decade-plus served to intensify such fastidiousness. At the age of 18, he became the youngest ever recipient of both the Leonard Bernstein Award (established by SHMF and named after one of the festival’s founders) and Gramophone‘s prestigious Young Artist Award (other recipients include countertenor Jakub Józef Orliński and soprano Natalya Romaniw). Having worked with a range of celebrated conductors (Claudio Abbado, Daniel Harding, Antonio Pappano, among many others) and orchestras (Staatskapelle Dresden, Bavarian Radio Symphony, London Symphony Orchestra, to name a few), his playing has been described as “pristine, lyrical and intelligent” by The New York Times. This month sees him playing Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 1 with Marin Alsop and DR Symfoni Orkestret in Denmark, before a series of dates in the U.S., both solo recitals and appearances with the Pittsburgh Symphony conducted by Pablo Heras-Casado. In November Lisiecki tours Europe, performing Schumann’s Piano Concerto with the London Philharmonic under its new Principal Conductor, Edward Gardner.

Amidst his busy live calendar (which, like many artists, extends years into the future) Lisiecki had long planned for a recording of Chopin’s nocturnes. Recorded in Berlin in October 2020 and released in August 2021, the work shows a distinctively thoughtful approach to the famous, widely beloved pieces. Chopin wrote the series of works between 1827 and 1846, expanding on a form developed by Irish composer John Field (1782-1837). Unlike other piano forms (sonatas, for instance), nocturnes do not possess a sort of programmatic narrative or formal structure, but mainly utilize a ternary form (ABA) which emphasizes a main theme and its related contrasts and embellishments. With a song-like right hand melody and the use of rhythmic, broken chords in the left hand, Chopin, in writing his own set, also utilized pedal effects and counterpoint in his composition to underline sonic tension and drama. There are a number of scholarly papers and debates around the tempos and role of rubato in the nocturnes, and the influence of such choices in relation to interpretative fidelity and style. In her 1988 book Performance Practises in Classic Piano Music: Their Principles and Applications (Indiana University Press, 1988), Sandra P. Rosenblum writes that “choice of tempo is a fundamental yet elusive aspect of performance practice. Tempo affects virtually every other aspect of interpretation: dynamics, touch, articulation, pedalling, realization of ornaments” and also observes that a pianist’s choice of tempo will certainly affect “what the listener perceives, hence it bears directly on the effectiveness of the interpretation.” Lisiecki has notably chosen to take a much slower tempo in his recording than many of his famous forebears, an aspect which has been questioned by some since the album’s release. If I may inject a personal view here, Lisiecki’s choice of tempi allow, to my own (admittedly non-conservatory-attending/music-degree-holding) self, a very thoughtful and lovely listening experience, one that skillfully combines intellect and imagination in ways that highlight the rhythmic nature of the writing (for both hands, equally) and the thought-to-word-like manifestation of clear creative articulation; such willful (nay, conscious) turning of the gears well reflect the sort of late-night contemplations to which the nocturnes directly refer. Don’t we all muse thusly in the middle of the night? This may not a so-called “traditional” reading, but, it doesn’t have to be – not for whatever perceived musical validity is deemed important by the classical world, let alone for one’s personal enjoyment. As musicologist Richard Taruskin argues in Text and Act: Essays in Music and Performance (Oxford University Press, 1995), traditions “modify what they transmit” via what he terms as “active intervention of the critical faculty, but also by what we might call interference.” Such traditions, he writes ( and most particularly within “a musical culture as variegated as the Western fine art of music has become”) are open to what he views as “outside influence.” It is this act, of combining inner critical faculty with various forms of external influence, combined with understandings of tonality, structure, and dynamics, that lends Lisiecki’s interpretations such innate power. Taking this course with such well-known works only serves to underline the pianist’s powerful blend of intellectual and musical instincts, and only makes one more keen to hear how he might re-adjust them for a live and considerably larger setting.

Despite, or more accurately owing to, the realities of the current pandemic era, Lisiecki was provided the an atmosphere conducive to the personal. The combination of simplicity (a room with a piano), proximity (or lack thereof, in relation to engineers), and the natural light in which Lisiecki recorded at Meistersaal (in Berlin) last autumn was, as he noted recently, good for encouraging a sort of natural approach, one which is so easily perceived on this, his eighth release with Deutsche Grammophon.

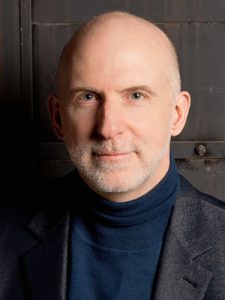

Photo © Christoph Köstlin / Deutsche Grammophon

What struck me about your album is how you personalize everything, but without sitting and steeping in a so-called sentimental sound. Your tempo choices, for instance, are well considered.

Well, I might not agree in ten years about them, but at the moment I did them it felt right, because, to be honest with you, those tempos choices were completely natural in the sense that I had no knowledge of them being that much slower. I’ve played the nocturnes a lot, in concerts and otherwise, and I know how I feel about them, some in the studio just ended up being like that. Listening in the booth and going back and forth, it never felt unnatural. I’m happy with it; I think it’s a good reflection of how I connected with (Chopin’s) music.

You didn’t consciously say, “I want this one to be this specific tempo” or do any sort of preplanning then?

No, definitely there was no, ‘Everybody’s playing these too fast; I’ll be much slower!” – I was recording the material at the tempo in, I guess, the way it felt right.

To me it makes them seem almost like speech if that makes sense…

Yes!

… it very much has the sound of somebody musing in the middle of the night on something; as a writer I like that.

Aw thank you Cate, I appreciate it.

But you recorded this in Berlin, in a space with natural light, during the day; did that make a difference energetically?

Let’s say, first of all I’m an artist and musician who plays concerts in the evening but I like working in the day; I’m not an evening practiser. I finish my work day of practise by 2 or 3pm, if I can, so to me recording during the day is when I feel most comfortable. What I like about natural light is feeling I’m connected to the day and not in a studio, especially since it was late October. During the day, the mood in Berlin, if you know Europe during the winter, is grey and bleak, so it’s nice to have those few hours of sunlight inside and you don’t feel like you’re missing out, and also then you can find your own space within that environment. It’s a beautiful hall, a rectangular room with high ceilings, and it’s rather ornate, not excessively so, but has some ornate elements, and feels nice to be in, the piano in one corner, the microphone in another area; it felt very natural.

It seemed like an environment where you weren’t completely in a bubble, cut off from everything, but just separated enough to be with your thoughts.

Exactly, and I’d had enough experiences of concert halls with no audience during the pandemic; it was nice to have not have yet-another-empty-concert-hall, but a studio with a piano, it almost felt like you were in your own studio practising for yourself, or working just for yourself.

That’s how it sounds.

Yes, and another sort of relevant fact, in terms of the sound, is that the booth where the recording engineer was sitting is quite a distance away from the (room with the piano), it’s down two flights of stairs and then across a hall, so it takes a fair bit of time to get from the room to the booth, and as a result, first of all, you’re more focused on doing something, it was a complete thought whenever you did sit down, and second of all, you have that crazy walk back and forth to get you out and into the mood accordingly.

And nobody behind a pane of glass staring at you and evaluating.

Right.

Now, recording in a space in these times, there is something unique about doing these extremely well-known works, and in this particular pandemic environment; how much were you able to pull down the blinds, or did you not want to? Was the act of recording amidst a worldwide pandemic an essential part of the creative process, or did you block it out?

It was definitely part of my process,and that’s part of the reason that I was able to record during the pandemic. I’d been thinking or dreaming about recording the nocturnes for a long time; it was a long-term project, not something that just came up, it was something which was a very conscious thought for years, and so it involved years of preparation, and those years of preparation are connected to wanting to experience (the works) in a concert hall – they are very personal as you said, but you run the risk while playing them of going too far in that direction, of going too far into your comfort zone, which is not where it feels the best when you are onstage, when you feel you’re losing the audience’s attention, when you can feel their attention wandering away. I can hear when that happens.

So to play and program 21 nocturnes onstage took many many many years, it’s something that I was preparing for, and happened to reach a culmination point this past year, and at the beginning of the pandemic, in March, Deutsche Grammophon said, “Oh, you’ll have fewer concerts, so let’s record this in August!” and as it got closer, I saw that things were very uncertain and people were antsy still, and I was supposed to have a few concerts but they were much more stressful than usual because there were so many external layers involved. I didn’t know how they’d look and be, and I would not have been in the right frame of mind at all. And then from March to October I did have things to do, I had things beyond music I was enjoying, and had the opportunity to do – like work in the garden or go camping with my dad, or not do anything for a whole day, which was very nice – but I could also work on the nocturnes in a much more relaxed sphere of mind, it wasn’t forced like I had a fixed deadline to prepare for and get to a certain point with. I could prepare and think through each one of them. That time right before the recording, to be honest, I was quite busy, I had something like ten concerts with Manfred Honeck and I was playing the Shostakovich First Piano Concerto in Dresden, it wasn’t like, “Oh sigh, I’m at home!” but some of the (moments leading to recording) felt calm, everything was calm, and I had to make peace with the pandemic and with the uncertainty it brought. Because of that, I could simply focus on what I was doing.

Living day-by-day has always been my motto; I’ve always lived in the present, but the pandemic has really heightened that. I like looking forward, I like to think “Well, I’m playing this concerto two years down the road” and “In two weeks I have to prepare this piece” – but all that went out the window. So it was, “Okay, what am I doing right now? What can I enjoy right now?” In this case, what with recording, it allowed me to focus, and to enjoy the moment.

That’s palpable in the recording, and I hear something different every time. Listening to the left hand can really bring something alive that one thought one knew well.

That’s palpable in the recording, and I hear something different every time. Listening to the left hand can really bring something alive that one thought one knew well.

If the music is only a sum of its parts, if you don’t pay a close enough attention, then you can risk the music becoming too comfortable, and being too happy with the gorgeous melodies; you just completely tune out everything else because it’s easy, it’s just, “Oh, the left hand, sure, whatever, put it away!” and the right hand, “Yes, let’s enjoy that, it’s so lovely!” But it doesn’t work musically. That (balance) has always been something important to me in playing Chopin. Of course there’s a principal theme and an idea and the harmonizing in the left hand, but sometimes the interplay between right and left creates completely new concepts and I do like finding those.

To me you can hear it in other things of his, or things written around the same time, but I find it takes the right interpretation to find those connections.

That’s right.

Obviously you know the other recordings; did any stick in your mind as you prepared?

I tend not to listen to other interpreters when I’m actively playing something unless it’s a concerto and I want to hear the orchestra, which of course includes a pianist, but in the case of the nocturnes I didn’t hear any interpretations for at least a year before recording them. Perhaps it wasn’t conscious – it was not a forced effort – but I just had no need to, because I’m living and experiencing these pieces on my own, and that’s a huge privilege. I know the audience listening to these works who come to the concert hall don’t have that same privilege for the most part, to simply play something for themselves, so they have a different appreciation of what it means to listen. When I’m listening to a recording, I find it very hard to get into the right mood to enjoy it as opposed to analyze it, so I tend not to, especially with regards to pieces which I’m actively playing.

Of course, that being said, I do respect other interpretations, and the ones that accompanied me through my childhood and longer, into my life, are those by (Anton) Rubinstein. He recorded all of the nocturnes, and there’s a sophistication about his playing; it’s always so elegant, so poised, it’s hard to find any fault with them… it’s just beautifully done.

Yes, I have that set! I wanted to ask you with relation to others and individual identity, some have said, “Oh it’s a Polish pianist playing Polish music!” I’m not sure if that kind of a reduction is good or bad for art, but I wonder what you make of such an assumed connection.

I think Poland, of course, likes to claim Chopin as their own, and they have a complete right to do that, but he lived most of his life beyond Poland, his composing and adult life, so undeniably that (experience of living abroad) did shape his writing, and likewise, while I was born in Canada, I do have Polish roots, and without a doubt they must also shape how I approach Chopin, although I never had a Polish teacher and I never really liked the so-called “Polish sound” in playing Chopin, which has a lot of rubato, it’s very rich, quite swingy, and not at all my taste. Now, this is a sort of stereotypical description, and there are exceptions – I love how Zimerman plays Chopin, for instance – and so that’s a rather unfair stereotype perhaps, but it’s an easy thing just as much to say or assume, “Oh you have special affinity for him then, being Polish yourself?” It’s hard for me to say, because I am who I am, and I don’t know how I’d be if I wasn’t – if I was born in Poland, or if I didn’t have those roots, but I appreciate his music as a person and an artist. I just like it , and I feel very comfortable playing his music. I can sit in front of a score I’ve never seen before and feel, “Ah yes!” – I have a vague understanding of what I want to do, and how I will play it, which cannot be said for every composer. I will get to a point, eventually, that isn’t that straight-forward, but (the inherent understanding) speaks to how he wrote for the piano; his musical language is very familiar to me, and he wrote so beautifully for the instrument. It doesn’t feel to me like I’m ever struggling to find a way to solve any problem (within the work).

Do you find you approach other musical things differently now, having had this time with Chopin and especially, this time with Chopin during a pandemic?

Again, sort of like the Polish question, I don’t know how it would’ve been if I didn’t record during this time, but I do feel everything has an impact and shapes the way one approaches music broadly. I think the sort of calmness that has pervaded, or became constant during the pandemic… for me, I will certainly take it with me into the future, though I can see and am hopeful of course it all turns out, and that life is getting back to normal in the some parts of the musical world. Some countries are getting back to normal, so the natural thing is to feel like, “Oh I’m going to get back to my old self now – at last!”… but it’s not quite like that. The pandemic has changed our values and understanding, in the same way it’s changed the approach to the nocturnes, and I’m glad I had that chance of recording them amidst all of this.

What’s it been like for you to go back to live performance then?

There have been many stages, because last summer I played one of the first concerts live, if not the first in Germany, in June 2020. So if you think of the situation in Canada then, like… wow, just nothing… and it was the same in some parts of Europe in many regards, except where they were starting to experiment, and those experiments kept going and going, and there was a palpable excitement with each one. And after each lockdown this excitement kept building in the performing arts world – I experienced it so many times, and everyone had different concepts of how long they’d be locked down, so even though I had been playing live a while, everybody was so excited, and asking me “How does it feel to be back?” And I’d say, “Well last week I was playing a live concert in Spain!”

I was always happy to play live, but the difference for me is, I’m not a fan, at all, of streams. I prefer not to play if I have to do a stream, for the most part. It doesn’t have any aspect of what I cherish in music. Live art is live, and it should stay with those who are there, those who have shared that experience and felt its power. Recording is high quality: you prepare, you put a lot of thought into it; you have the best environment; you have the studio, the piano, the technician, the sound engineer. But streaming is somewhere in-between these things; it’s not live for an audience, it’s not the same high-quality sound you expect – in fact, it’s usually poor-quality sound. It was interesting to see orchestras doing streams, and it was good to see that musicians were playing, that they had the chance to play – but just me playing solo, no way, no – I’m not doing that, at all.

So you need the feedback?

Yes. And you know, people say with these streams, “Well of course live art will die now” – no it won’t. Many people will be happy to go back to the concert hall the moment they can. But until then, to be honest, we have such a rich array of performances, both live recordings from pre-pandemic times and things recorded in a studio, and we haven’t had time to listen to those during normal our lives – why don’t we go back to those amazingly high-quality things and listen to them? Instead of choosing to watch something live, just because…? Others will disagree but I’m happy to argue with them.

There’s a tremendous drive on the part of marketing departments everywhere to get people of your generation interested in classical music through streaming…

… but that’s not the strength of our genre. The strength of our genre is in the concert hall. It’s about this extraordinary experience you will sometimes have… sometimes. I play hundreds of concerts a year and not every single one will be magical, either it’s me or the piano, it’s something in the hall, or the day, or the circumstances outside – whatever. You will have those extraordinary experiences a small percentage of the time, and everybody remembers them. Many who’ve never been to a hall happen to chance on those magical concerts and they’re suddenly a huge fan of classical because they had that experience of intimacy which provided a foray into the musical world of live performance.

And you think that epic and imitate combo only happens in a live environment?

Exactly, yes.

That’s what this music demands – and the light/dark dualism of these songs has a corollary in the isolation/community themes which seem particularly meaningful right now.

That’s what this music demands – and the light/dark dualism of these songs has a corollary in the isolation/community themes which seem particularly meaningful right now.