Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Toward the end of her life my mother would chide me for what she perceived as prolonged screen time. “You are always at that damn computer,” she’d sigh, “but I suppose you have to think about your audience and what they’d like to read.” What with everyone spending longer and more concentrated time in front of screens amidst the current coronavirus crisis, the lines between education, entertainment, and enlightenment can be fraught indeed. As an educator and writer, I frequently have to balance my desire to share information with a deeply-held urge to entertain, and then be able to skillfully juggle the added ball of measured impact. Those of us whose work is largely based in or around the internet (i.e. writers, artists, musicians) are at the mercy of ever-changing algorithms; we want to have our work seen, but we want to keep our voices and ideas intact. Playing to the desired young audience many classical institutions now eagerly pursue should, I suppose, be a priority, but playing to such an audience is not easy when you are no longer young yourself, not comfortable changing the nature of your work (or its presentation), and have an innate awareness that it is not desirable (or very dignified) as an aging woman with highly specialist passions and specifically artsy tastes, to attempt to compete with young/cute/sexy/etc. And yet, to note one’s work being read, shared, engaged with, and sense it is having an impact – it is gratifying. To play to the algorithm, or not to play to the algorithm; this is the question.

This juggling act can become even more complex when it is one’s modus operandi to impart what you feel is vital information whilst providing a modicum of inspiration which might (possibly, hopefully) encourage independent exploration, on and off the screen. Gresham College has been able to do all of these things, with incredible style and success, specifically through its Russian Piano Masterpieces series, featuring Professor Frolova-Walker and pianist Peter Donohoe. Introduced in September 2020, the series consists of what can only be described as lecture-conversation-concerts – in-depth, one-hour explorations of the history, structure, harmonics, and socio-economic-creative contexts of composers and their respective (if oftentimes linked) outputs. Frolova-Walker specializes in Russian music of the 19th and 20th centuries, and has published, lectured and had her work broadcast on BBC Radio 3; along with being Professor of Music History and Director of Studies in Music at Clare College, Cambridge, she is a Fellow of the British Academy. In 2015, she was recognized for her work in musicology and awarded the Edward Dent Medal by the Royal Musical Association. Peter Donohoe, CBE, is a celebrated international pianist who, since his winning the 1982 Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow, has worked with a range of conductors, including Yevgeny Svetlanov, Gustavo Dudamel, and Sir Simon Rattle. He has appeared at the BBC Proms no less than twenty-two times, and is steeped in the music of the composers who are featured in the series, though he also has vast experience with the music of Tchaikovsky, whose music Frolova-Walker had also wanted to include as part of the series, as she explains below.

The wonderfully easy rapport between Frolova-Walker and Donohoe – their mix of playfulness, intelligence, insight, experience, and genuine love of the material – makes the series a special event amidst pandemic gloom, and their impressive viewing numbers seem to confirm this. Algorithm or not, the series has hit a nerve with numerous classical-loving, culturally starving viewers; newcomers and old hands alike have been tuning in faithfully these past six months and interacting with good-humoured ease, judging (if one dares) from the comments shared and exchanged during live broadcasts. Indeed Frolova-Walker and Donohue do have their sizeable and frequently overlapping fan bases, but it’s heartening to note the embrace with which those fans have greeted a virtual presentation, and just how welcoming the community has been to newcomers. It was something of a thrill to chat recently for thirty minutes with Professor Frolova-Walker, whose work and style I have long admired, and to discuss not only the series itself, but wider ideas about classical music’s youth appeal (or not), how and why fashion intersects with events (or not), and the steep digital learning curve experienced by educators and artists alike over the past twelve months. The next presentation in Russian Piano Masterpieces is scheduled for Thursday, March 25th (at 6pm GMT), and explores the music of Sergei Prokofiev; the following presentation (the final one in the series) is on May 20th, about Dmitri Shostakovich.

How and why did this series come about?

Good question! When I applied to Gresham College I secretly was hoping I could get Peter to collaborate with me. Gresham College has been so proactive in using a different venue they don’t usually use, because we needed a piano. About a year ago we found out they managed to secure it, and I was absolutely delighted because it’s such a wonderful venue, everything is there; of course we couldn’t imagine how it would turn out, because it was planned as a live event, always. It was *never* supposed to be online. I mean, the online presence of Gresham College lectures was always an afterthought – it’s not the main thing, so you shouldn’t imagine we planned it as an online series at all – but emotionally it started with this great feeling of despair that we could only get 15 people. The next time we couldn’t get anyone, and then we got used to it. Now we’re just grateful for the opportunity, even if it’s in an empty hall! Really, it’s been a learning curve.

I would imagine part of that curve has involved upping technological skills, as has been the case with so many in the classical world.

I’m not sure I can claim anything in that field, really! The big moment was when, a year ago exactly, I was told I would have to do my other course, my Diaghilev lecture series, online; that was really… I was in complete panic, because basically I’m a person who draws energy from the audience. About 50% of my energy comes from the audience, from improvising in front of an audience, and in seeing their reactions. And suddenly, to not have this energy… I thought, “I can’t do this; I can’t write out text and read it. That isn’t me. I can’t do it properly!” So that was I think the worst, the steepest learning curve. It was primitive what I used – I just recorded myself and it was edited by someone else, but I had to actually speak to the camera and still have it be lively.

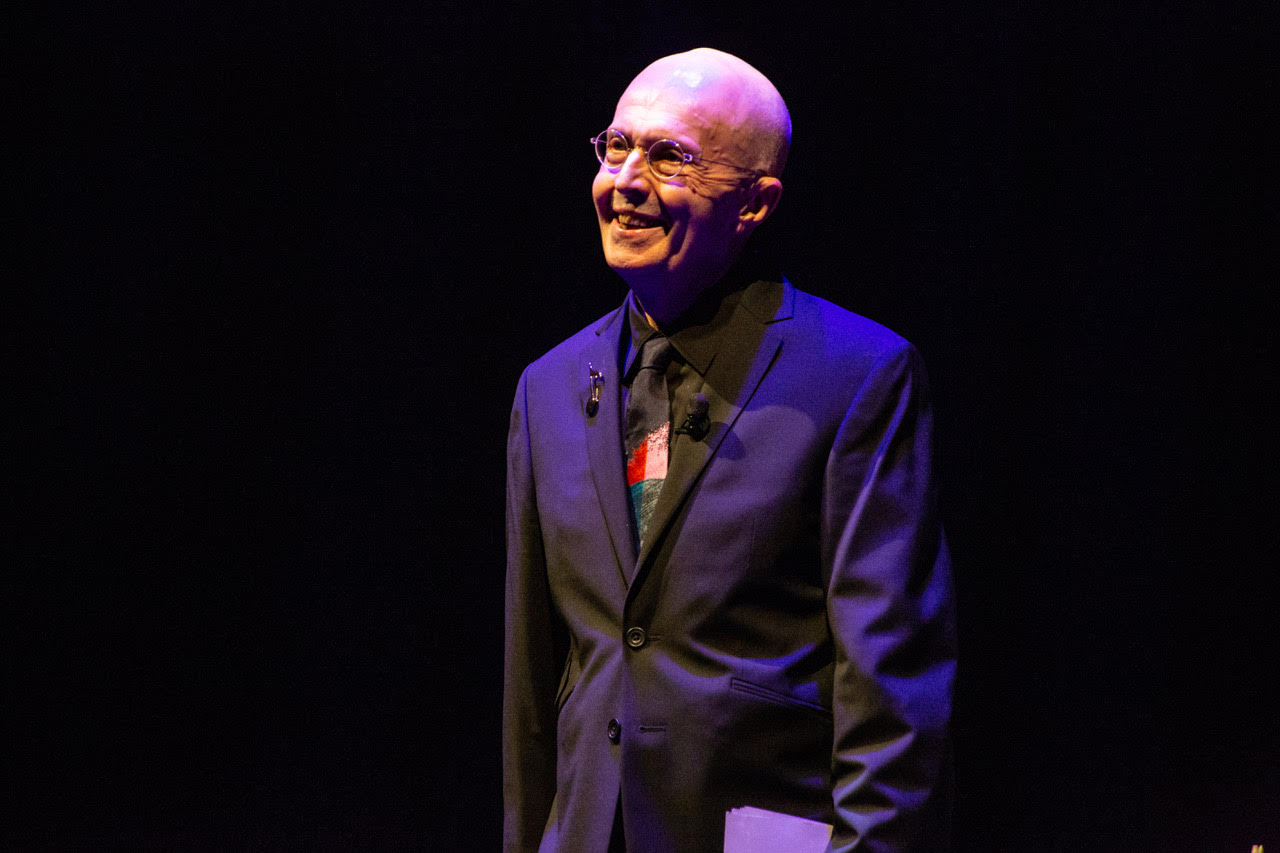

Photo via Gresham College

I find you very engaging – knowledgeable, passionate, with a really good understanding of pace and structure; I wonder if that’s because you have an artist’s understanding of the role of audience already.

It’s just something that was given to me. I think it’s one of the few gifts that I *was* given. Really, it’s not a gift of speaking coherently at all! But there’s something about connecting with an audience, which I was able to do since I was 19. I did my first lecture at that age, at a college in Moscow, and there were these students completely bored; they were basically forced into this room, it was their cultural program, they had to be there, and I was talking about Bach, and something just clicked at a certain moment, and they seemed to be really enjoying it so it was an opening. And I realized, “I want to do this” – but I don’t know what I do or how. It is just something I suppose I am predisposed to doing. And I’m sure I could learn to do it better, but I wouldn’t know how.

There has been a learning curve for everyone; my own output has been transformed and I’ve had to learn to release the need to know the immediate impact of my work on others.

It has been difficult, doing a series of undergrad lectures in an empty room, and there’s no connection! The previous year I was doing them so much better because I had the power of the audience. But what can you do?

Nothing. But it’s so hard sometimes…

It is!

… but things like your series help. How did you choose these composers and which pieces of music to feature in each segment?

When I was choosing which six to feature, it was very difficult because I had at least seven I wanted, but because I knew I’d be working with Peter, I looked at what he’d recorded and would play or remember, to bring it back to mind. One that is missing is Tchaikovsky; I would’ve loved to have had the music of Tchaikovsky as well, because Peter has a wonderful recording of his Grand Sonata and it’s a very I think undervalued work – people think it’s very loud and goes on forever, and I think it’s wonderful! So yes, Tchaikovsky had to fall off, but generally you know, I had some ideas of stories I could tell about some particular works, but then very often Peter would say, “Well let’s do this instead” and though it’s not what I planned it works perfectly, because there is no audience, and it’s not a concert. So it makes more sense to break things up, I think, and show different pieces in different ways.

Part of that method involves you and Peter trading various moments; how do you and Peter decide on these trade-offs in speaking, or do you just wing it?

I think you can guess!

I want you to tell me.

I think he believes in improvisation as much as I do, and you do, probably.

I do.

Right. So there is a certain amount of preplanning, but I think the interesting thing about this, and my thought behind it was, I’ve always known the way musicologists talk about music is very different from the way performers talk about it; I discovered that very early on when I travelled with a quartet. I was supposed to give a lecture about Shostakovich’s 8th Quartet and then they’d play it; on the train (with quartet members) I was telling them my ideas and they were like, “Wow, we would’ve never thought of it in this way!” and some of them I know, like other performers, find some of these things weird. So I’m kind of… I know that some of the things musicologists say about music are completely opaque, and possibly the other way around is true as well, so these are two different approaches, and my idea was to see whether they can go together and whether people in the audience can gain a third thing which might emerge. As to what is working or not, it is not for me to judge.

Photo via Gresham College

So musicologists, performers, and audience are in this interesting triangulation of musical reception and experience within the context of live experience specifically; where do you see the role of online presentation?

My idea, my vision for it, is that in principle (the series) can grab the attention of someone who is not into piano music, who is not into music at all, who doesn’t read notation or know many things about this, that they would get something out of it, maybe very different things from what what you could get out of it, or what my students would get out of it, or my colleagues would get out of it. Ideally I would like that *everyone* will get something out of it, and that’s why I think also, this series is so multilayered; those who, say, want to do a project on Shostakovich’s piano music, can watch it and stop and look at the slides, and get much more out of those slides than during the lecture itself, and download the transcript – which of course is not really the actual transcript, because I wrote it before the lecture, but it has references on things we cover. There is depth in it, and depth in varied slides. I don’t have time to address everything when we’re presenting it live, and especially when it’s an improvised performance, but I am secure the content is there, and if somebody wants to get at it in a deeper way, they’d be able to.

Do you imagine your potential audience and write to that, or… ?

You get a little bit of feedback on things, not ever, of course, as you would like, but you get a bit, and I know that some of my former students for example who work in schools, show it to their pupils, who are A-level music students. I know there are music lovers who tune in, but there are also people who are just into Gresham College lectures overall – because Gresham College lectures are amazing. I started getting into them as well, for instance, I listened to a lecture on bell-ringing and mathematical patterns, and about 25 minutes into it I was completely lost, the mathematics side stopped making sense, it was too complicated – but I could still enjoy what I got out of it. It’s still valuable as an experience. My attitude to everything, basically, is it’s better to have a part of something and not be a purist, instead of having the attitude of, “I don’t understand this at all; I won’t bother getting into it.” I think it’s the same with classical music. When you first listen to a Wagner opera you get about 5% of it, then after 30 listenings you get maybe 20% of it; I think this is very important for people who want to get into classical and feel it’s too forbidding. It’s a reminder not to be too hard on themselves.

Having things laid out clearly, with intelligence and confidence, and letting people use their imaginations as well, is a good way to introduce the classical idiom overall, I have found.

Yes, I think it’s good too – I mean, notation is such a hot topic right now, but it’s why I use it. I think even for people who’ve never seen it before, it’s like a diagram: you understand it when (the piece) goes up and when it goes down, and that’s all you need to know. The time goes like this, you have these two axes like that; just from those elements, you can get quite a lot. You can see how many notes there are, how fast it goes – roughly – so with this very basic knowledge you can get quite a lot of comprehension, just by looking at two bars of music, even if you don’t know what it sounds like.

That’s just it, and then having the immediate experience of hearing Peter play what might be shown too...

It’s amazing. I think the last lecture we did Peter sight-read a piece just straight off the screen – the whole piece! It was so funny!

When I spoke to John Daszak about singing reductions he mentioned working with Peter on the Das Lied Von Der Erde piano reduction and how he found it louder than the full orchestration, and Peter’s playing in particular to be very full-on.

People who would have been in the room to actually hear the sound… it’s *astounding*. What a loss not to hear him live. Our little group from Gresham College has been obviously privy to this, and myself, and you realize this kind of piano playing is completely on a different level; there’s nothing in common between how I play the piano and how Peter plays the piano, it’s just a different thing. First of all the range of sound, the range of pianissimo to fortissimo is six times bigger – he can be very loud but he can be very quiet too – and also the control is amazing, I don’t know to what extent… we are in the hands of the technical team, so many things can go wrong, but really, the live-ness can never be replaced.

I hear your lectures and all I want to do is hear these pieces live.

That’s nice to hear! Maybe we’ll have a CD sale at the last lecture. There’s a tiny bit of hope that by the 20th of May we’ll have an audience, but we’re not worried about this now, we’ve gotten used to it the way one gets used to chronic illness or chronic pain, but it’s not something you want to necessarily have permanently. When the restrictions are lifted I think, people will realize what they were missing.

Some, but it’s different for everybody.

I think you know this well, that what we need to realize is that there are different generations who have very different relationships with online. My son, for example, was born online and he lives online, and to him, it’s different, so I’m sure, he would enjoy things in the real world, so to speak. His attitude to online things is *very* different, and for that young audience I think the idea of a short video or something that is not actually a full-scale lecture but a short video, really well done and well presented, professionally done, expensively done, is the best possible teaching aid. And I think he would prefer those things to reading books, to having live lectures, I have a suspicion that young people think very differently about these things.

But then when you get them in the concert hall or opera house they are quite shocked at what they’re hearing –in a good way, but shocked nonetheless. “What do you mean it’s not amplified?!” etc…

Oh, it’s amazing, yes! But here we get into the ritualistic side of it, and also I found out by talking to him, for example, what would prevent him from coming into the Royal Opera – I would always demand he would put on some smart clothes. I was shocked by this. He wants to hear the music but feels there is something alienating and hostile about the audience, and you know, he feels he can’t really wear normal clothes. And that’s something we have to fight. It really was shocking for me to hear that.

I find the correlation between dressing up and elitism bizarre; I dress up because I enjoy it, but I haven’t done it every single time I’ve attended an event.

I dress up as well – because I’m Russian, we tend to dress up, it’s normal to go out of the house to the bakery dressed up, so it’s a different attitude. There’s a big long explanation for it, I am sure – Russia never had a hippie culture, for example – so the idea of casual clothing is, for us, still a bit alien. For my son, who is 18 right now, he doesn’t want to make that effort, and also I think, if I meet someone who knows me and say, “This is my son” – he hates that, so that’s another reason he won’t hear a Wagner opera. But I said to him, “You can wear what you like and be completely separate from me” – and that was the pact.

So did he go?

He‘s seen the whole Ring cycle, and he knows it’s amazing – he could feel the fire in Walküre because he was in the 2nd row! He said, “I could feel the heat… !” Really, he loved it.

If you can get young audiences exposed like that even once, they’ll get it.

Some of them will come back, I think… some. But we need this kind of thing, of just going at all; we used to have this sort of cultural exposure in Soviet Russia. We used to have concerts for children, and for teenagers, and you had to go to them with your school – you had to go to a symphony concert, it was not a choice. And for 80% it meant nothing, but there would be that 20% who’d get completely hooked.

So your series feels like the next logical step for people who are curious, young or not…

I think that’s probably why I can do this so easily with Peter – he thinks the same; he’s very open, he can talk to anyone about these things without trying to create a mystique about any of it. I mean obviously there is a sense at some point where we say, “The rest we can’t explain because it’s magic, it takes you over” – but there are lots of things you can explain in an ordinary way, with very simple language, and that’s what we try to do.