May traditionally brings flowers, rain, more flowers… more rain, as well as abrupt temperature shifts. Those shifts might be a good metaphor for today (May 9th), a day fraught with many things, or possibly nothing, depending on where you happen to be. The whole month feels like a deep inhale before the intense demands which come with many summer music festivals. The following reading list includes oodles of opera, bundles of Beethoven, and little bites of chewy foods for thoughts when it comes to memory, live presentation, and seelenökologie; it also includes (I hope) a little bit of room to breathe.

In a personal sense, today marks 4o days since the passing of my godfather, who experienced his first opera at the age of 87. (More on that below.)

Spring has sprung – inhale, exhale, slowly; repeat.

Live Live Live (& Read)

My review of Medea (the Cherubini version), currently being presented by the Canadian Opera Company in Toronto, can be found here. Soprano Sondra Radvanovsky, who had been scheduled to sing the title role, was forced to cancel the remainder of her performances during the run. Italian soprano Chiara Isotton is taking over. TL;DR: See if you can; Isotton is truly great.

Médée (the Charpentier version) is currently running at Opéra de Paris (Palais Garnier), with mezzo soprano Lea Desandre receiving much acclaim for her titular performance, together with conductor William Christie and Les Arts Florissants in the pit. The production is, like Medea, directed by Sir David McVicar, and was first created for English National Opera in 2013 before receiving a staging in Geneva in 2019. The presentation marks the first time Charpentier’s opera has been presented at Opéra national de Paris since 1693. It closes on Saturday (11 May); allons-y!

An opera that made its premiere at the Opéra Garnier: Guercœur by Albéric Magnard, in 1931. The work, which has a tragic real-life backstory, is enjoying a renaissance with Opéra national du Rhin having just finished a run in Strasbourg; the Christof Loy-directed production will be subsequently be presented in Mulhouse, on the 26th and 28th of this month, with baritone Stéphane Degout in the lead. The 2024-2025 season sees another presentation of the work, by Oper Frankfurt and featuring baritone Domen Križaj; the production will be directed by David Hermann with Marie Jacquot (and later Lukas Rommelspacher) on the podium.

Among the many offerings at this year’s edition of The Dresdner Musikfestspiele is the event “Silent Voices In A Noisy World” which features the music of Amélie Nikisch (wife of conductor Arthur Nikisch) and Rachel Danziger van Embden (a student of Wagner biographer Jacques Hartog). Condensed piano versions of Nikisch’s 1911 operetta Meine Tante, deine Tante (My Aunt, Your Aunt) and Danziger van Embden’s operetta Die Dorfkomtesse (The Village Countess) from 1910 will be performed at Dresden’s Palais im Großen Garten, with arrangements, curation, and moderation by Dr. Kai Hinrich Müller, who, as I wrote last month, is spearheading a series of events this year for The Thomas Mann House connected to the formal theme of Opera & Democracy. The Dresden concert is part of this initiative, and is also part of the Musica non grata program, both which I will be writing about in more detail as part of my upcoming conversation with Müller. The interview will be posted later this month; stay tuned!

Also on Sunday: a performance from Rundfunk Sinfonieorchester Berlin at the city’s Konzerthaus featuring soprano Camilla Nylund (singing Strauss’s Four Last Songs) and led by Finnish conductor Tarno Peltokoski. In a recent exchange with Helge Berkelbach at Concerti, Peltokoski discusses his debut album with Deutsche Grammophon (Mozart symphonies), his passion for Wagner’s Ring Cycle, and the importance of clarity over emotions when standing before an orchestra: “Wenn ich beim Dirigieren von Wagner in meinen Wagner-Gefühlen schwimme, macht das überhaupt keinen Sinn. Ich meine, das Orchester wüsste nicht, was es tun soll, und das Publikum hätte auch keine Freude daran.” (“If I’m swimming in my Wagnerian feelings when I conduct Wagner, it makes no sense at all. I think the orchestra wouldn’t know what to do and the audience wouldn’t enjoy it either.”) Peltokoski’s responses belie his youth (he turned 24 last month), and I am curious to follow him on what may well be a very interesting journey involving Wagner, Strauss, and… ? We shall see.

Speaking of Wagner journeys: Wagner In Context (Cambridge University Press, 2024) has recently been released and it is a delectable slow read. Divided into clear themes (places, people, performances, politics), the book, edited by Cambridge Professor David Trippett, offers an assortment of thoughtful takes on varied aspects of the composer’s work and his impact on modern classical culture. Featuring essays from a wide range of contributors – including Barry Millington, Mark Berry, Katharine Ellis, Leon Botstein, and Gundula Kreutzer (whose book Curtain, Gong, Steam: Wagnerian Technologies of Nineteenth-Century Opera has been on my wish list since its release in 2018) – this is a book which quietly demands slow digestion. I hope to speak with Trippett in the coming weeks about the book and Wagner’s enduring socio-cultural footprint; stay tuned.

Progressive…ish?

Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission. (Collection Bode-Museum, Berlin)

In the new and not-so-new realm: a recent article published at The Stage provides food for thought on serious issues which reach well past the immediate British opera landscape. Quoting analyses released in March by Arts Council England, writer Katie Chambers includes thoughts from a variety of figures including Opera North general director and chief executive Laura Canning, Musicians’ Union general secretary Naomi Pohl, and stage director Adele Thomas, who offers a valuable insight: “The critical response to the way that any feminist interpretation gets greeted with has forced [opera] to give us a flatter representation of what women are.”

At a time when many houses engage in self-congratulatory gestures on what they perceive as a wonderful form of progressivism (the examples are really not difficult to find), it’s interesting to note how many tow a traditional line at heart, particularly in the years since the worst of the covid pandemic. Approaches promoted as “progressive” often employ straight-male gaze wrapped in the coat of creative inquiry (italics mine); question it and you are deemed stupid or uptight, or (gasp) woke. I’m not sure what will change within industry except for the way productions are dressed (more accurately, undressed) via publicity teams and traditional media, an element Thomas rightly acknowledges:

We are at the tail end of a generation of opera critics who don’t question how much of their opinions are internalised misogyny rather than a genuine reaction to what is in front of them. No criticism to them – it wasn’t what they were asked to do at the time of learning their trade. But it has to change. (“Opera in crisis: leaders warn sector issues go beyond funding woes” The Stage, 7 May 2024)

I hope to speak with various critics in the future about this issue, and explore their ideas on risk and live presentation; it would be good to have their takes on the role of criticism in 2024. I want to have faith that there’s value in its continued practice –even as arts criticism quickly vanishes, everywhere – so again: stay tuned.

“Freude, schöner Götterfunken!”

Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Speaking of expressions of faith: Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony celebrated the 200th anniversary of its premiere on 7 May 1824. An assortment of German music publishers posted fascinating histories, including photos of the original score. The birthday of the symphony has also inspired various documentaries – one by German broadcaster DW (in English), and another by Canadian filmmaker Larry Weinstein (Beethoven’s Nine: Ode To Humanity), recently screened at the Toronto-based Hot Docs film festival. A recreation of the first concert in which the Ninth Symphony was performed took place in Wuppertal (with period instruments), and there are more concerts on the horizon including performances by Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique in London and Paris, with a performance of the Ninth Symphony on the 29th of this month at St Martin-in-the-Fields, where they’ll be joined by the Monteverdi Choir & Chorus.

Amongst the many essays and articles which have appeared recently is one from Gramophone magazine (“Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony: the greatest recordings“, Richard Osborne, 7 May) outlining important aspects of the work, including Schiller’s famous text, and (hurrah) giving equal attention to all four of its movements. Osborne examines interpretations of the symphony by a range of conductors including Otto Klemperer, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, and Wilhelm Furtwängler, and includes concomitant sound clips for each. Like many articles, Osborne also mentions Leonard Bernstein famously replacing the word “freedom” (Freiheit) for “joy” (Freude) in Friedrich Schiller’s text at a concert in Berlin in late 1989, just after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Whether or not one agrees with that replacement, Bernstein’s gesture was entirely in keeping with the mood of the times, a symbol of the way in which the work has been presented throughout various epochs.

Conductor Vladimir Jurowski references Bernstein in a recent written feature for BR Klassik, exploring the work’s links to historic events as well as personal memories, some of which are tied, quite touchingly, to portions of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. He also shares his thoughts on initially tackling Beethoven’s Ninth as an artist (“der Mythos um diese Symphonie herum kann einen auch erzittern lassen” – “the myth surrounding this symphony can also make you tremble”) and his decision to program the works of 20th and 21st century composers prior and sometimes even between movements. This approach to such a famous work brings to mind something he said to Hamburger Abendblatt journalist Joachim Mischke (in a podcast from earlier this month) about “Ökologie des akustischen Raums und seine emotionale und geistige Wirkung auf auf die Menschen” (“the ecology of acoustic space and its emotional and spiritual impact on people”). The idea of “seelenökologie” (soul ecology), especially within programming and live presentation in 2024, is one well worth considering, because of course it requires embracing experiences which move past the expected pushing of little emotional buttons – an experience that might be uncomfortable to some.

The first symphony concert I ever attended was a performance of a Beethoven’s Fifth led by Sir Andrew Davis. Roughly a decade after that, I experienced my very first live Beethoven’s Ninth, and by that point, I had formed opinions on how things should sound, and which emotional buttons I expected to be pushed. The performance happened to coincide with the night of my high school prom, but being a perennial outsider, I had no one to go with and I wasn’t too terribly interested anyway (or at least I told myself that at the time). Aside from the discomfort of a heavy velvet dress unsuited to a warm June evening, the most powerful memory from that time is of my hot teenaged fury at the tempos taken through a good portion of the performance; they were faster than what I was expecting, and they came as a total shock. How dare the orchestra not push my little emotional buttons! The whole experience was highly uncomfortable… but: my hate eventually withered and bloomed into real appreciation, dare I say love of this approach, though it took study, maturity, patience. Thank goodness for the local library in aiding with the bloom.

Big Reach

My first formal job, in fact, was at a library –retrieving, sorting, and reshelving books. Library services have expanded considerably since then, but essential purposes remain: the exercise of curiosity, and easy access to the results of that exercise. Cue those elements within a classical-viewing context now, thanks to a partnership between broadcaster Medici TV (who specialize in classical content and stream more than 150 live events annually) and Hoopla (an online borrowing system not dissimilar to Kanopy). Medici’s collection is now accessible to libraries in North America, Australia, and New Zealand. You just need a library card – and yes, the medici.tv/hoopla borrowing system works in Canada.

Another form of easy access comes courtesy of Wigmore Hall in London, which has a long history of presenting livestream broadcasts. Soprano Ermonela Jaho is set to perform live from Wigmore Hall on May 23rd as part of Opera Rara’s second ‘Donizetti & Friends‘ recital. Jaho, who is Artist Ambassador for the organization (dedicated to presenting little-heard operatic works from the 19th and 20th centuries), will be joined by its Artistic Director, conductor Carlo Rizzi, and his brother, violinist Marco Rizzi. The concert will be livestreamed on Opera Rara’s Youtube Channel and will be available for viewing for 30 days.

Space & Time

Speaking of viewing: the work of Alexander Calder is enjoying a special exhibition in Switzerland. Calder: Sculpting Time includes over thirty works which were made between 1930 and 1960 and explores what host MASI Lugano calls “the fourth dimension of time into art with his legendary mobiles.” Many of the pieces on display include items from the artist’s Constellations series, which he began in 1943. Calder won the grand prize for sculpture at the 1952 Venice Biennale and went on to be awarded the Legion of Honor in France and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in the US; he worked across a variety of media, creating not only sculpture and mobiles but set and costumes designs, jewelry, and immense public installations. The MASI show seems a little more intimate, but the imagery at the website also conveys Calder’s signature knack for spatial integration: the epic and the intimate; the intellectual and the sensuous. There is a certain joy (Schiller’s Freude, maybe) in all of it, and particularly through the live experience.

Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce.

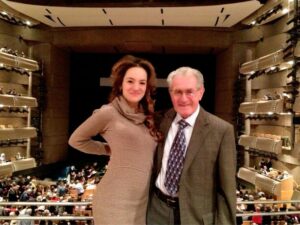

Referencing that live experience, and as promised: my godfather enjoyed his very first opera just after his 87th birthday. He passed away at the end of March. Lately I’ve been thinking back on our times together, that 2017 visit to the opera very much included. Those who knew about our connection (and that opera visit) have asked me what we saw (Tosca) and more specifically what he thought of it all (he liked but didn’t love it, though did express interest in German-language works, specifically Die Fledermaus). He was mostly happy to finally be experiencing the thing my mother (with whom he had been very close) possessed such a passion for, and he was grateful for my initiative in taking him.

At his passing my godfather had been in Canada for seven decades but he never forgot his Swiss roots, and made a point of playing folk music (complete with yodels) on his stereo system during our visits. “It isn’t opera,” he would say, sipping brandy, “but it’s a little bit of home.”