Just before Easter, I wrote about a memorable musical experience in which I sang in a language I didn’t speak, to music I wasn’t completely familiar with. It was a haunting, beautiful series of moments I still recall fondly and often; I thought about the experience, in various facets, listening to Yiddish Glory: The Lost Songs of WWII (Six Degrees Records), a very unique collection of songs which, again, are in a language I don’t speak, but which have a powerful impact, and, as it turns out, a very powerful history.

There are stellar performances from an array of gifted musicians here, including Russian singer-songwriter (and album co-creator) Psoy Korolenko, Juno Award-winning artists Sophie Milman and David Buchbinder, longtime Yehudi Menuhin collaborator Sergei Erdenko, and many more. Lyrical, sad, funny, and very feisty, the album, released this past February, is made composed entirely of works written by Holocaust victims and survivors during the Second World War. They offer not only unique and important historical perspective, but a creative lesson in resistance, resilience, and fierce, vibrant resurrection. The sheer force of musicality on offer here is noteworthy, but combined with the power of the lyrics and their history, makes for a profound, joyous, and very moving listening experience.

Anna Shternshis (Photo: Roman Boldyrev)

Anna Shternshis, who is Al and Malka Green Professor in Yiddish Studies and Director, Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Toronto, helped to put Yiddish Glory together. Professor Shternshis discovered the songs while researching a book about Yiddish culture in the Soviet Union during the Holocaust. As she told CBC, “I stumbled upon this collection of Yiddish songs and something seemed off about those songs, […] They were about Stalin. They were about fighting against Hitler. They were about Central Asia. These were the songs in Yiddish I’d never seen before.”

Currently on a music/speaking tour for the album, with stops at Center for Jewish History in New York City and Purdue University last month, Northwestern University’s Chicago campus earlier this month, and Montreal today (May 13th), Professor Shternshis took time out of her busy schedule to discuss the album and its creation, its significance in cultural and historical terms, the role of humour, and the twin timeliness and timelessness of the songs.

Psoy Korolenko performing live. (Photo: Roman Boldyrev)

How were the pieces on Yiddish Glory chosen?

Singer Psoy Korolenko and I worked together on bringing these pieces back to life as music. We selected songs that would give voice to the amateur authors of various backgrounds — women, children, soldiers, refugees — who composed music and poetry under the most difficult circumstances, and therefore provided some of the first testimonies of what it was like to live in the Soviet Union during World War II. Each individual composition has its own story, and together, these songs reveal a collective history of an entire generation, they provide an artistic comment on the Jewish experience in the Soviet Union during World War II.

How did you feel when you discovered the history behind these works? It must have been a very dramatic moment.

The work of a historian consists of many hours of monotonous research, and this project is not an exception. But when I began analyzing the lyrics, and understood that these were grassroots accounts of Nazi atrocities, and that none of these songs had been known before, emotions took over. I felt excited about reading these materials, and strongly moved by the lyrics. Above all, I felt enormous gratitude to Moisei Beregovsky and his colleagues, Soviet ethnomusicologists of the 1940s, who spent years collecting these unique materials. They were arrested by Stalin’s government for doing so, and died thinking their work was lost to history without any recognition for what they had done. I felt professional solidarity with these people, who, of course, I never met.

What kind of a reception has the album and your work received in the places where these pieces originated?

When we began this project, restoring these songs as music, we hoped that these compositions that detailed the experiences of how Jews lived, died, tried to maintain hope and even love under the most horrific of circumstances would touch people. And indeed, radio stations and publications from around the world have been drawn to the project, including incredible coverage in Germany and Austria where so many have really come to grips with the dangers of fascism.

In Eastern Europe, we have received coverage in Russia, Hungary, Czech Republic (and others), but more on specialized media, as opposed to their national broadcasters. Back in the 1940s, when Beregovsky and his colleagues were preparing these songs for publication, many of the specific “Jewish” references in the lyrics were censored and replaced with Soviet terms. You can actually see the censor’s marks on the original documents. The researchers were eventually arrested for this work during Stalin’s anti-Jewish purge that began in 1948. The government wanted to stress how all Soviet citizens were victims during the war, even though the Holocaust specifically targeted Jews for their ethnicity. This tendency persists today as well.

Russian-language media abroad covered the project extensively. When we present these songs live, a significant percentage of our audiences are of Russian-Jewish descent, and these songs represent their heritage, and the broad range of their families’ experiences.

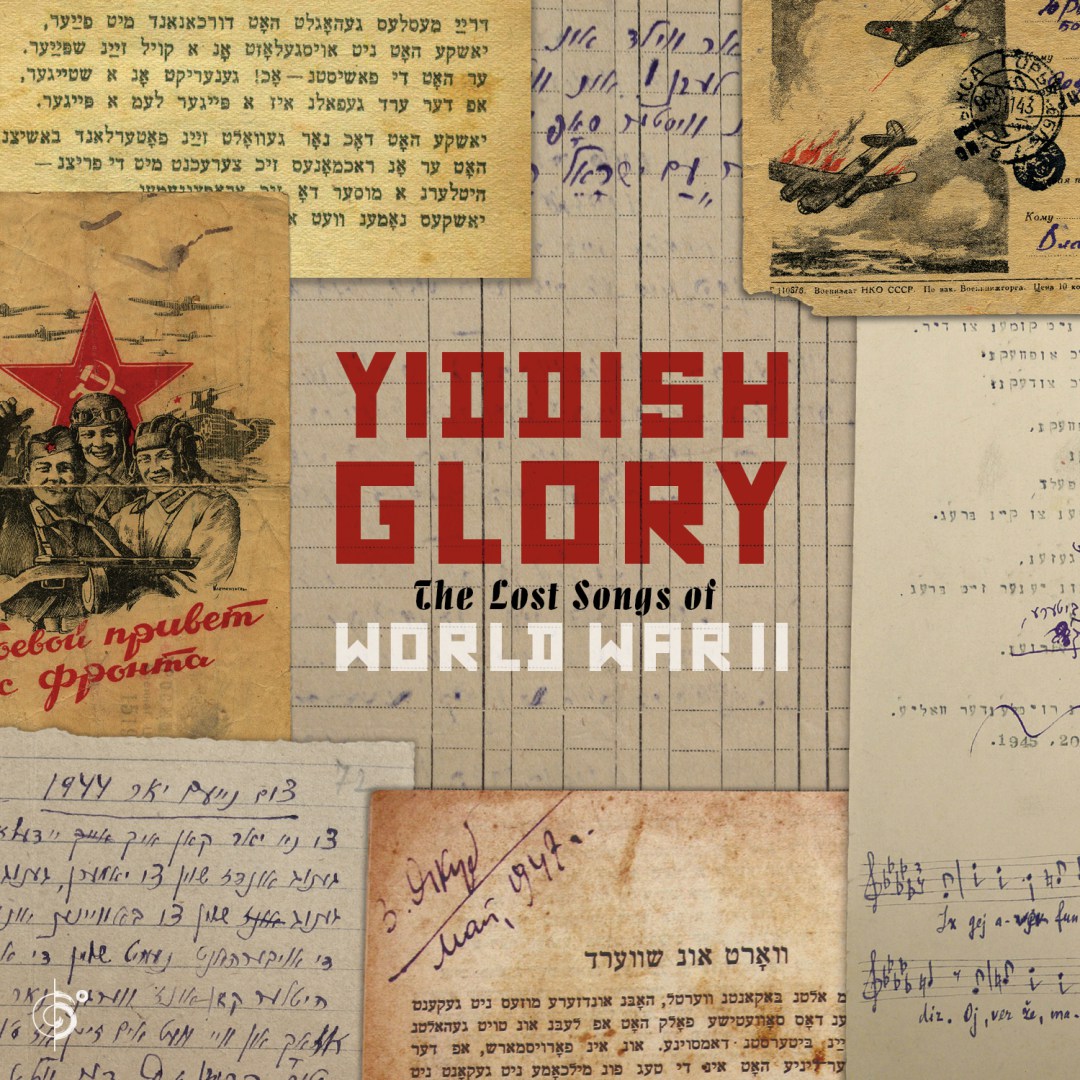

Cover to Yiddish Glory. The album was released by Six Degrees Records in February 2018.

Why these particular pieces? Do you have any favourites?

Each song was chosen because its lyrics conveyed a unique, often under-discussed historical experience, such life and survival in the Tulchin ghetto or in the Pechora camp, serving in the Red Army, working on the Soviet home front or fighting as a partisan. My favourites include one about a Red Army soldier singing about his machine gun that he uses to fight against fascism. Another favourite is one written by a child after losing his mother in Pechora. Both of these songs have raw emotional strength that just grab you by heart.

What do you think accounts for the humour that runs through some of these works?

Many songs are so called “motivation” pieces, written by and for soldiers to encourage them to fight against Hitler and his army. Many describe the exact death that Hitler should endure – such as being sliced into pieces. The songs are angry because they blame Hitler, rightly so, for destroying the lives of Soviet people, including, of course, Jews. The hatred of Hitler, expressed in these songs, is raw, strong and emotional. Their authors do not spare curse words. One song, “Misha Tears Apart Hitler’s Germany”, for example, says that soldiers will drive Hitler away in the manner one chases a wild animal.

Hitler is also an object of ridicule and satire. Many songs in the archive are humorous, sometimes based on the holiday of Purim, including “Purim Gifts to Hitler,” which compares Hitler to all of the failed enemies of Jewish people, including Haman. The song promises that Hitler, just like all other enemies of Jews, will end up being killed for his evil deeds. The fact that so many of these songs rely on humour is significant because laughing seemed to help people to keep their spirits up during horrific ordeals. Many survivors mention in their testimonies that if you can laugh at something, it cannot kill you. Songs indeed include ridicule of German soldiers running away with their pants down and Hitler dressed in funny clothes. Understanding that people wrote these songs during the time when the German army was destroying their cities and communities makes the presence of humour especially poignant and significant.

There is an interesting classical connection with some of these pieces, their melodies being based on the works of composers like Glinka; how is this important to their overall story and history?

About 80% of the songs in the collection did not have their original sheet music, so Psoy Korolenko had to analyze the texts to reconstruct them. He chose Glinka’s “Skylark” for “Yoshke from Odessa” because that song was very popular in the Soviet Union in the 1930s. It was inspiring to think about a soldier imagining himself as a popular Soviet tenor, and using (that particular piece) to tell his own both heroic and tragic story.

How do you think an album like “Yiddish Glory” changes our perceptions of this period of history?

One definite thing that we have learned from these materials is that Jews sang in Yiddish in the Soviet Union during the war, and that they forgot all about this decades later. During my work on a related project, on Jewish oral histories of Stalin’s Soviet Union, I interviewed almost 500 people from the generation of Soviet Jews born in the early 1920s, and not a single one of them could remember of a Yiddish song depicting the war. This material means that history and memory tell different stories of the war. Without these materials we would not have known that.

The second finding is that Soviet soldiers, some of them amateur authors, continued to create in Yiddish during combat. We knew that Yiddish culture survived in the Soviet Rear, but we did not know about the soldiers — this is an important insight of how Jews made sense of these events during the war.

Sophie Milman is one of the artists featured on Yiddish Glory. (Photo: Vladimir Kevorkov)

Also, these songs give us a chance to learn about how children and women, who authored a majority of these songs, used music to make sense of their experiences: there are songs written by orphans, one by a ten year-old whose mother was murdered in the Holocaust; there are songs written by women serving in the army, women working in factories to support the war effort. The works give us an opportunity to hear their direct voices, something that rarely happens in the context of historical research.

Also, some songs are rare — sometimes the only — eyewitness testimonies of the destruction of Jews in Ukraine. Some were written as early as 1941, and these represent the first documents of the Holocaust in Ukraine. Given that we have very few Jewish testimonies of this destruction, these are especially valuable.

Why this album, now? How do you see it as relevant (indeed, needed) in the 21st century?

The fight against fascism, racism, bigotry and antisemitism is timely. Unfortunately, violence and wars did not disappear in the 21st century. Women and children are often the first, and the least noticeable victims of it. The songs alert us to the dangers of wars and who suffers from it the most.