As I walked around Frank Lloyd Wright’s beautiful white spirals in the Solomon R. Guggenheim museum, I ducked into a special exhibition, Kandinsky At The Bauhaus, and… there it was, in all its orbular glory: Several Circles.

The Guggenheim website offers insight:

“The circle,” claimed Kandinsky, “is the synthesis of the greatest oppositions. It combines the concentric and the eccentric in a single form and in equilibrium. Of the three primary forms, it points most clearly to the fourth dimension.”

In its magnificent, lidless, concentrated, and sensually concentric presence, I sat, mouth agape, staring at its hip-swirling dance of color, form, light, and texture. The fourth dimension indeed. There are few things that take me so directly there as painting and the written word.

I write, every day, in a real, actual journal, with a real, actual pen. It seems almost quaint. In this world of iPads and iPhones and digitalthisthatandtheother, writing in a journal seems fabulously oldy-world-y, and vaguely old-fashioned. It takes more time to write than type; this forces a stewing of thoughts, a quiet, patient consideration and re-consideration, one that ultimately transforms expressions and observations and perceptions into stained, messy, occasionally wine-spilled musings that melt, all over the pages, like soft, salt-water taffy slowly expiring on the tongue. ‘Do I like how this looks on the page?‘ becomes every bit as important as, ‘What am I trying to say again?’ and I’m often surprised at how much I miss my journal the times when I go out and forget it. I don’t always use it; it’s more an observational talisman that makes me look at things -and smell them, taste them, hear them, feel them – a little more closely.

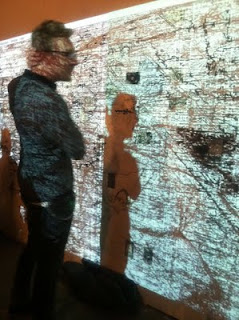

I write, every day, in a real, actual journal, with a real, actual pen. It seems almost quaint. In this world of iPads and iPhones and digitalthisthatandtheother, writing in a journal seems fabulously oldy-world-y, and vaguely old-fashioned. It takes more time to write than type; this forces a stewing of thoughts, a quiet, patient consideration and re-consideration, one that ultimately transforms expressions and observations and perceptions into stained, messy, occasionally wine-spilled musings that melt, all over the pages, like soft, salt-water taffy slowly expiring on the tongue. ‘Do I like how this looks on the page?‘ becomes every bit as important as, ‘What am I trying to say again?’ and I’m often surprised at how much I miss my journal the times when I go out and forget it. I don’t always use it; it’s more an observational talisman that makes me look at things -and smell them, taste them, hear them, feel them – a little more closely. So I was delighted to attend an event celebrating the tactile -recently. Called “Objectivity”, the event was held at Eyebeam, a digital art space on the west side of Manhattan. The event was part of A vocabulary of objects, a formal Moleskine event that saw workshop participants make their very own journals. On one side of the sprawling warehouse space, a massive piece of paper had been tacked onto a broad wall that dominated one side of the room. It had a mottled projection across it; black drafting pencils had been set out to encourage attendees to add their own markings. People were riotously, joyously drawing as they balanced glasses of prosecco and chatted. I added to the markings with a few wild lilies. I didn’t see one person texting or talking on a phone – only drawing, drinking, watching, creating, and connecting.

So I was delighted to attend an event celebrating the tactile -recently. Called “Objectivity”, the event was held at Eyebeam, a digital art space on the west side of Manhattan. The event was part of A vocabulary of objects, a formal Moleskine event that saw workshop participants make their very own journals. On one side of the sprawling warehouse space, a massive piece of paper had been tacked onto a broad wall that dominated one side of the room. It had a mottled projection across it; black drafting pencils had been set out to encourage attendees to add their own markings. People were riotously, joyously drawing as they balanced glasses of prosecco and chatted. I added to the markings with a few wild lilies. I didn’t see one person texting or talking on a phone – only drawing, drinking, watching, creating, and connecting. And so, the Moleskin event At Eyebeam was a bit of heaven, here and now in New York City, 2011, amidst the hub-bub of technology and the joy of digital connectivity. Those have a place. So do the tangible arts. Being able to draw with total strangers felt like a strong reaffirmation of the vital role of the tangible in everyday life. Even as we ostensibly move further away from experiencing daily life with our five senses, at the same time, we move closer to it, taking pensive, tip-toe steps into that “fourth dimension” Kandinsky referred to. Can we make it? Can we commit? I freely admit to being addicted to the bonbons of modern life: Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, Soundcloud, Linked In … blogging. But I’m circling back to sensuality, being reminded, in tiny spiraling whispers, that I never left. That fourth dimension is beckoning me, to enter, and re-enter, again and again. I want to keep walking, I’m curious what I’ll find in the middle, on the outer rings, and along the way. Stained fingers? That…and a whole lot more.

And so, the Moleskin event At Eyebeam was a bit of heaven, here and now in New York City, 2011, amidst the hub-bub of technology and the joy of digital connectivity. Those have a place. So do the tangible arts. Being able to draw with total strangers felt like a strong reaffirmation of the vital role of the tangible in everyday life. Even as we ostensibly move further away from experiencing daily life with our five senses, at the same time, we move closer to it, taking pensive, tip-toe steps into that “fourth dimension” Kandinsky referred to. Can we make it? Can we commit? I freely admit to being addicted to the bonbons of modern life: Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, Soundcloud, Linked In … blogging. But I’m circling back to sensuality, being reminded, in tiny spiraling whispers, that I never left. That fourth dimension is beckoning me, to enter, and re-enter, again and again. I want to keep walking, I’m curious what I’ll find in the middle, on the outer rings, and along the way. Stained fingers? That…and a whole lot more.