The extent to which concert and opera-going habits have changed as a result of the coronavirus pandemic is slowly becoming known. Recent announcements suggest that many organizations are playing it safe (or what they perceive as safe) in offering reams of favored classical chestnuts for 2022-2023 seasons in order to entice audiences, both old and new, back into the concert halls and opera houses. Any semblance of challenge is being left largely within the parameters of individual approaches – an interesting twist on “make your own fun”, perhaps – but one might still wish such notions (challenge, individual thought, critical thinking) hold some form of value in the post-pandemic classical landscape. I would like to believe that the idea of challenge – and its first cousin, curiosity – do indeed matter, and that whatever choices are (or be perceived as) over-cautious within future programming might be somehow reconfigured in order to open the door to more careful, contextualized listening / live experiences. As someone fascinated by how sounds transmit both verbal and non-verbal meaning, it has become a natural, near-unconscious habit to listen not passively but passionately. My ears, as I remarked to someone recently, have grown teeth; everything is evaluated with an intense energy and attention to detail. Developing incisive listening (and seeing, and evaluating) skill, however unconsciously, does not, despite being a music writer, always bring benefits; such habit is now perceived in some quarters as churlishness, over-criticism, over-analysis, even (heaven forbid), ingratitude (“You should be grateful live music is back at all!”). Yet this aural and visual approach, one now so useful amidst so many programming announcements, is not to be turned off or hidden, but rather, used in the interests of feeding curiosity, furthering inquiry, broadening the field of discovery.

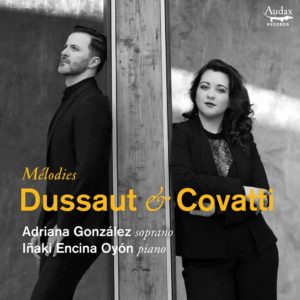

So what a treat it was, to come across the album Mélodies (Audax, 2020) by soprano Adriana González and Basque pianist/conductor Iñaki Encina Oyón earlier this year. Featuring the largely-unknown songs of French composers Robert Dussaut (1896-1969) and Hélène Covatti (1910-2005), the album is a stellar showcase of González’s immense vocal talents, conveying a strong sense of the Guatemala-born soprano’s immense gift in integrating sensitive interpretation and smart technical approach; comparisons to the late Welsh soprano Margaret Price (1941-2011) come to mind, and have been rightly noted. The natural chemistry between González and Oyón share is evident through album’s 22 tracks, with the soprano’s coloration, phrasing, and textures matched by the pianist’s poetic tempos, touch, and dynamism, creating a luscious showcase of the hauntingly beautiful writing of each of the respective composers. “Adieux à l’étranger“ (1922) is a wistful work, Dussaut’s writing recalling the lyrical qualities of Massenet, while Covatti’s “Berceuse” shows clear connections to Ravel and De Falla; in each, González’s skillfully modulates voice and dynamics with and around Oyón’s delicate, intuitive playing. Mélodies is a very rewarding, very captivating listen, one that provides a wonderful introduction to both the composers and to Gonzalez’s larger talents, tantalizingly hinting at the explosive intensity which she so ably channels in live performance.

So what a treat it was, to come across the album Mélodies (Audax, 2020) by soprano Adriana González and Basque pianist/conductor Iñaki Encina Oyón earlier this year. Featuring the largely-unknown songs of French composers Robert Dussaut (1896-1969) and Hélène Covatti (1910-2005), the album is a stellar showcase of González’s immense vocal talents, conveying a strong sense of the Guatemala-born soprano’s immense gift in integrating sensitive interpretation and smart technical approach; comparisons to the late Welsh soprano Margaret Price (1941-2011) come to mind, and have been rightly noted. The natural chemistry between González and Oyón share is evident through album’s 22 tracks, with the soprano’s coloration, phrasing, and textures matched by the pianist’s poetic tempos, touch, and dynamism, creating a luscious showcase of the hauntingly beautiful writing of each of the respective composers. “Adieux à l’étranger“ (1922) is a wistful work, Dussaut’s writing recalling the lyrical qualities of Massenet, while Covatti’s “Berceuse” shows clear connections to Ravel and De Falla; in each, González’s skillfully modulates voice and dynamics with and around Oyón’s delicate, intuitive playing. Mélodies is a very rewarding, very captivating listen, one that provides a wonderful introduction to both the composers and to Gonzalez’s larger talents, tantalizingly hinting at the explosive intensity which she so ably channels in live performance.

Winner of the First and Zarzuela Prizes at the Operalia competition in 2019, González has performed with Oper Frankfurt, Gran Teatre del Liceu, Opéra de Toulon, Opéra national de Lorraine, Opera Naţională Română Timişoara. Most recently she made her American debut with Houston Grand Opera, singing the role of Juliette in Gounod’s opera Roméo et Juliette opposite tenor Michael Spyres. This month sees Gonzalez perform Verdi’s Requiem in Portugal, a work she will perform again later this year with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra; other roles next season include Michaela in Carmen (with Dutch National Opera, Paris Opera, and with Opéra Royal de Wallonie in Liège) and as Echo in Gluck’s Écho et Narcisse with Opéra Royal, Versailles. Having become a member of the Atelier Lyrique of the Paris Opera in 2014, González has developed a wide repertoire, one that hews to her rich if highly flexible lyric soprano style, with an emphasis on Mozart, Rossini, and Puccini so far. That doesn’t mean she isn’t prepared to expand her fach, but she does it with maximum awareness of her instrument – its demands, its realities, the stamina required and the ways it can be fostered with grace and sensitivity, all whilst simultaneously exercising a clear artistic curiosity. González’s recital with Oyón earlier this year in Dijon featured music from her Dussaut/Covatti album, as well as music by Enrique Granados (1867-1916), Fernando Obradors (1897-1945), Frederic Mompou (1893-1987), as well as songs from her recent album, Albéniz: Complete Songs (Audax), a 30-track exploration of the Spanish composer’s varied vocal oeuvre. Released last October and rightly nominated for an 2022 International Classical Music Award (ICMA), the album is a seamless integration of chemistry, technique, and artistry with González again delivering a stunning display of her immense vocality and feeling for the art of song.

As I learned when we spoke recently, González, while highly aware of her powerful, affecting sound, is also aware of her desire to stretch, explore, and cultivate her talent creatively, with a firm hold of context at every step. We started off discussing what it was like to quickly step into the role of Liù for a performance of Turandot in Houston, as she was concurrently performing Juliette. Stress, what stress? González seems too focused a performer to let nerves ever get the best of her, and her recollection of the experience was coloured more by a mix off excitement, disbelief, and gratitude than any dregs of self-doubt. González is as much earthy as she is studious, and that intensity I referenced earlier is, as ever, always in the service of a knowing approach to craft. Such a combination of ingredients makes for a meal that satisfies toothsome ears, and for a very rewarding form of listening amidst post-pandemic times.

As I learned when we spoke recently, González, while highly aware of her powerful, affecting sound, is also aware of her desire to stretch, explore, and cultivate her talent creatively, with a firm hold of context at every step. We started off discussing what it was like to quickly step into the role of Liù for a performance of Turandot in Houston, as she was concurrently performing Juliette. Stress, what stress? González seems too focused a performer to let nerves ever get the best of her, and her recollection of the experience was coloured more by a mix off excitement, disbelief, and gratitude than any dregs of self-doubt. González is as much earthy as she is studious, and that intensity I referenced earlier is, as ever, always in the service of a knowing approach to craft. Such a combination of ingredients makes for a meal that satisfies toothsome ears, and for a very rewarding form of listening amidst post-pandemic times.

When I learned about your quickly stepping into the role of Liù I reviewed my 2019 conversation with conductor Carlo Rizzi about Turandot, who called that character the heart of the opera. What was it like to step into that world so quickly?

Musically it was quite something – but I didn’t do the staging. They had me singing from the side and had an actor doing the staging tagging because Robert Wilson’s Turandot is very precise in terms of movements. The actress didn’t know the music really well, so (the production team) were talking to her through an earpiece and she had someone telling her, “Walk here, do this, do that, step left, one step back – no you stepped too far” – for her I can’t imagine what it was like. For me of course Liù is such a different vocality from Juliette, it was like, “Okay, go for it!” In Roméo et Juliette I thought, “Keep it proper, it’s French” and with Puccini, well, it’s home very much for me vocally, but I hadn’t sung Liù since 2019 and in doing it recently I thought, “Oh my voice has really grown, it’s changed, this feels different” – so that was wonderful. And the conductor, Eun Sun Kim, is amazing; every entrance was so clear, she would be waiting attentively at other moments; she knows the text of everything. She was there every step. It was like, “I know my part but I’m glad you do too!”

You said in a past interview that in preparing for a role you go over the vowel sounds and various details of vocalizing. What has it been like for you to examine the sounds within the text – has your process changed? I’m thinking here specifically of your doing Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta in Paris in 2019.

Iolanta was difficult because I don’t speak Russian and it was a secondary role – it was Brigitta, one of her nurses, and it was one of the contracts I did from the studio years in Paris. I had to do it but otherwise, I would be very skeptical to choose a role in an opera which is written in a language I don’t speak, because I find you really need to learn the language, you need to understand the cultural context and background from which the words originate. French is great for me: I know all the expressions; I find humour. When you see the phrases in opera, used in day to day, you can react better, just from an acting point of view –you can react better and propose things knowing the meaning of the text, from a technical and vocal technique point of view. You need to know the meaning of the word to know what kind of colour and what kind of nuance works also. For example, if you’re saying “I’m hesitating” then you don’t want to say “hesitating” or the feeling it implies so beautifully, it’s a feeling that doesn’t reflect something good – maybe it can be a good thing in the long run, but in the moment hesitation is doubt, it’s a feeling of unbalanced things. This is a lot of the thought process – you need to find a way of expressing that feeling clearly. And then of course we singers, we do these sounds and feelings through vowels, not through consonants specifically, so if you have vowel sounds, you need to make them a bit more acid if you are expressing a certain feeling, and you need to do it in a way so the whole experience of the word comes through. That’s the background we singers need to do even years before we start, just looking at the role and singing the role, because it’s muscular training you have to do to find those colours, and so you don’t get in trouble. You can’t do colours and really go for it with just your acting instinct. You have to take care of yourself, so that when you do those colours you’re not hurting your instruments. It’s a balance.

When I spoke with Etienne Dupuis earlier this year, he said how doing Don Carlos opened the door to many new things he hadn’t experienced singing it prior in Italian, but I wonder about the “acid sounds” – how much might such a vocal choice disturb perceptions of beauty in opera? If you’re concerned about making the expected “beautiful” sound you risk flattening the drama into this heterogeneous sonic mass, but committing to the sounds you describe means risking the way you – and your voice – are perceived by those who hold fast to notions of ‘the beautiful’ as paramount.

Tamara Wilson, who is amazing Turandot, dares to go piano, and it’s in those moments where you can really see Turandot’s vulnerability – and hearing that approach changes absolutely everything. It’s no longer this sort of scream-and-fight cliché– her performance has this power and this contrast, but also has length: the role is long enough that she can showcase all the colours she has. For some singers it is sometimes difficult. I did four years of young artist programs, and it was through that experience that I learned short roles can be just as hard; in a long role you have to pace yourself –when to do what –you have this amazing amount of time to showcase your whole palette. But with a short role, it’s just that little bit of time – I did a small role in Rigoletto, for instance – in which you can’t show a lot, but definitely when you have a longer role you make decisions on how to showcase the beauty but also the anguish, because opera is very much about real life. There are sad moments –you want to make people cry and think about beauty – but it also has to be real emotion. It can’t be beautiful all the time; there has to be a balance between the elements. There has to be a balance between where and how you choose the moments to really go for pain, and all else.

This speaks to theatre, does it not? To the power of theatre?

Yes!

Theatre is firmly part of what opera is, and indeed these operas – Turandot is Carlo Gozzi via Friedrich Schiller, by way of Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni; Roméo et Juliette is Shakespeare by way of Jules Barbier and Michel Carré. Do you, alongside opera recordings, examine the plays and/or performances of plays as part of your preparation?

I did read Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and I also heard an audio book performance of it, to hear the inflections of the language, and to hear how the pain of certain scenes was expressed through the words – some of those inflections of text were so powerful. I also listened because of (curiosity around) the stage movement; the Houston production has specific stage movement; we had to train to do and we rehearsed, but I find if the emotion and intention are clear, then that helps you, no matter how you move, no matter the specifics. The intention of the action is there in the background. I definitely went through that process and got a good feeling: “Okay this is a painful moment” Also it was good to compare Shakespeare to what Gounod took for his final libretto – it’s very different. There are varying characters who are emphasized or not emphasized, and the family feud (in Gounod) is in the background compared to what Shakespeare presents. Also I couldn’t help but notice Juliet’s cheekiness – she’s very cheeky in Shakespeare; Gounod’s Juliette is more fragile and sentimental.

How much was working with Michael Spyres (as Roméo) an aid to the process?

From the first day Michael and I clicked really well. I’m a World Youth Choir baby – I did that really young, that’s what sort of got me to Europe – and I had always heard about Michael Spyres, as he was also in that choir as a kid. We’d heard of each other too – all of our friends know each other but we hadn’t actually met ourselves, but then we did and it was like, “You! Yes, you!” We clicked immediately – it was a wonderful meeting. Working with him was fabulous. He’s such a professional, he knows how to manage his instrument and be expressive, and he’s so much about the text also. It was a beautiful and natural collaboration. Even outside of the duos, he’s someone who really listens to what you’re doing – I listen to what he’s doing also. The first time we did a run-through, we did it one way; the second time was comp different because we were listening to each other so intently, so we felt good to make changes already. He’s a wonderful colleague. I couldn’t have asked for a more wonderful Roméo. Even without verbal language, it is so clear we are so much on the same page.

Michael Spyres and Adriana González in Romeo and Juliet at Houston Grand Opera. Photo by Lynn Lane.

Singers often emphasize chemistry – either it’s there or it isn’t. That’s important in a romantic opera, I should think… ?

It is important! It’s also a thing connected to life experiences. Talking with Michael, we’ve shared a lot of life experience, him and the countries he’d lived in, and me from Guatemala. Certain experiences create a certain way of thinking. Even if we grew up in different countries, he’ll say something about what he saw and I’ll say, “Hey, that happens in my country too!” So the life experiences are shared and create the way you behave and interact. That was also something that added to our work relationship.

And somehow the details, as you say, fall away. When you are doing this kind of project you can still come from your different places with all the related cultural backgrounds, but the meeting point somehow still exists, and that meeting happens in opera, and on record. Your album of Dussaut-Covatti is a good example, though I confess I hadn’t heard of the composers before hearing it…

That’s totally normal!

I don’t feel so bad now…

Don’t feel bad, seriously!

When you refer to chemistry, that is something definitely evident with your pianist, Iñaki Encina Oyón, through these songs; why make an album of their work?

I’m glad the complicity Iñaki and I have comes through. Now why do I say it’s normal not to know these composers? Because they are very unknown! The project came out of a very personal project for Iñaki and myself; the two composers, Dussaut and Covatti, are the parents of Iñaki’s piano teacher from Toulouse. When he left Spain he studied piano and conducting in Toulouse, and his piano teacher was the pianist Thérèse Dussaut (b. 1939), daughter of Hélène Covatti and Robert Dussaut. Thérèse doesn’t have children and she is getting older, and at the time she said to him, “Hey you know a lot of singers, why don’t you take my parents’ music and see what you can do with it?” Iñaki has such a curious brain, he loves to read and discover old composers, he digs for music all day, and one day he said, “Adriana let’s sight-read this.” The songs fit my voice so perfectly – the way it’s written was perfect with the tessitura and with the French. We went on to have a lot of fun performing them in recital. One day we decided to record them because otherwise, we worried they’d be lost to history – most were manuscripts, so we made a new edition of the scores, and recorded the album. The composers have so many other works – and Robert Dussaut was awarded the Grand Prix De Rome, the biggest composition prize you can win in France, he got it back in 1924 – it’s a prize Gounod won also; although Gounod only got it the second time he applied (in 1839, for the cantata Fernand), and Dussaut won it the first time around. It was music that had also not been done, and so it was wonderful to not be compared to anyone else and do something not done ten-thousand times already. The record label, Audax, is also independent, and their slogan is “Stay Curious” – they basically do unknown works, mainly Baroque and instrumental things, but are slowly taking on voice also.

As to Iñaki, that starts World Youth Choir also, like Michael. In 2012 Iñaki was the Assistant Conductor of the project and I was a choir person who did a solo, which I auditioned for. He heard me and said, “Where do you come from? What is this voice? Where did you train?” I said, “I want to sing Mimi!” I was 18 or 19 years old, and he said, “You know there’s the opera studios…” He informed me of all of these programs and how things work in Europe. I’d never left Guatemala – and a year later he invited me to Paris to do a production with him and invited the director of the Paris opera studio with whom he’s very good friends – Christian Schirm – and they got me the audition for the Paris casting people. It turns out they needed a Zerlina for the studio and took me in and asked me subsequently to stay in the program. And, all of that happened because of Iñaki, and his selflessness in wanting to help young talent. So I really owe him everything, he’s a wonderful friend and travels where I am singing – he came from Paris to Houston to see my Juliette debut, for instance. He’s really a close friend. So when you say the chemistry comes through on the album, that is really a wonderful compliment! We worked so hard on that album, and to express what’s written in the scores.

And now you’re shifting gears entirely, to Verdi’s Requiem. How do you prepare for something like this, especially something you’ll be performing across different continents?

When I accepted I thought, wait, should I have taken a longer pause between things? But it’s definitely something I did not want to turn down – the first one in Portugal at the end of May came as a proposal from Lorenzo Viotti. His sister Marina Viotti is doing the mezzo solo and she is one of my best friends. I thought, I’m not missing this opportunity to perform with my friend, and especially when it’s a first time for both of us! And also with her brother, I thought, really I can’t say no to this – so I will try to pace myself.

For singers, as a bit of context here, we are athletes, so we have to train vocally how we’ll use our muscles for the different types of writing from different types of composers. Gounod is different, specifically Juliette, to Verdi anything, of course. The wonderful thing is that the Verdi Requiem, if you look at the score, has many piani written and you have to keep a more slim position, a certain sort of throat opening, let’s say it that way – you can’t go full throttle, and doing a role like Juliette has helped keep that youth in the voice. Also having done a rebel kind of a Juliette has helped build the stamina for doing the Verdi Requiem, even with such different writing styles. I’ve learned the whole of the music and I’ll have a week to switch over from the Gounod to the Verdi – it’ll be a lot of training over that week. I’m slowly adapting my muscles and stretching them in a different way so I’ll be prepared to do Verdi. It’s such an iconic piece, and there’s been lots of reading, lots of analyzing, considering how to phrase the music – how to place this or that vowel; how to breathe in this place or that; how to make the larynx go into position so I can get a specific colour at a certain point –and how to get there fresh, so I can achieve that sound needed at the end of the Requiem but still have this sound of youth for the beautiful phrases at the very beginning.

Stamina is the right word – but it’s a different kind of stamina required for Verdi’s work rather than Gounod’s. How might this experience and the preparation for it carry over into future roles?

It takes a lot – but you do think about it: what decisions to make when; what roles to take on; what do I want to do in the next five years. My voice will go into Verdi repertoire. I want to still enjoy the roles I’m doing now – Mimi, Liù, the Contessa, Fiordiligi. A Desdemona in the middle would be wonderful too…

That’s a role I’d love to hear you do.

It’s one I’m really looking forward to doing – and I am going in that direction, slowly. It is where my voice is headed – but you need to know how to pace yourself. In past times singers would do 60 shows a year for one role; now it’s like, we do 4 shows… and, can we do more, please? It takes so much time and effort and knowledge and, again, time… to prepare a role and then you do 4 shows, and you think, well, I hope I get to do this more!

That’s why the covid era was so devastating; singers trained five years out for roles in operas that were cancelled or moved. I want to believe the industry learned something from that time, but I’m not so sure… what’s your take?

It’s definitely been a time that’s made us think slower, so we were not just jumping around from one thing to another without a thought. It’s been a reminder of the importance of taking the time to do your things with dedication – dedicating time to the music, time and energy the music deserves, not jumping from one thing to another, but just focusing on one thing. Do that one thing wonderfully, then close the book, turn the page, go to the next thing. It’s very important to be this deliberate, and it’s the key for a long career also, to do one thing at a time, and to focus on it, and give yourself time and space also. I mean, God knows before in the opera world, in the Golden Age as it’s called, travel wasn’t that fast, it took how long to get to the American continent from Europe –you had days to recover from your performances, and you would travel on the boat, and then have a production in the US. Rehearsals were different also, so much was at a slower pace. There’s a lot to remember and to think about from that era in terms of taking time to enjoy things, and to enjoy the music itself.