Brindley Sherratt as Sarastro in the 2019 Glyndebourne Festival production of Die Zauberflöte. (Photo: Bill Cooper)

Like many in Europe right now, Brindley Sherratt is trying to stay cool. I chatted with the English bass in the middle of a brutal (and record-breaking) heatwave, where he spoke to me from his residence in Sussex, a two-hour drive south of London. “It’s not so bad… but it’s still 35C!” he said. “I have a huge fan on my desk here.”

Sherratt came to singing relatively late – his mid-late 30s – and, as he told The Times last year, missed out on the young artist training programs and thus “I consider myself about 50 years behind my colleagues in some respects.” This later start might work against some singers, but with Sherratt, it’s quite the opposite; the circumstances offer a gravitas that’s hard to miss onstage. His is an even-keeled, confident presence; he doesn’t make a big show of things vocally or physically, because he doesn’t have to. I experienced his darkly brooding Hunding earlier this year as part of a partial in-concert presentation of Die Walküre with the Sir Andrew Davis and the Toronto Symphony Orchestra (the opera’s first half was performed) during which he sung alongside Simon O’Neill’s Siegmund and Lise Davidsen’s Sieglinde, in a rich display of vocal dramatism shot through with relentless drive. At the time, I wrote about Sherratt’s performance as being “less outwardly murderous than inwardly brewing, an avuncular if charismatic figure of quiet intensity” and I think that’s a good way to describe him artistically; Sherratt is possessed of a quiet intensity, in both manner and – especially – in voice. (It’s a quality that also makes him a great villain.) His is one of those warm, enveloping sounds that does so much more than merely honk or bellow, but offers sonorous drama and clear delivery. Quite the combination.

Photo: Sussie Ahlburg

Despite the late start, Sherratt has enjoyed a busy career with appearances on both sides of the Atlantic (Metropolitan Opera, Brooklyn Academy of Music, Lyric Opera Chicago; Teatro Real de Madrid, Opernhaus Zürich, Wiener Staatsoper), with a concentration of work in the U.K. (Garsington Opera, BBC Proms, Royal Opera House, English National Opera, Welsh National Opera, Opera North), performing a diverse array of repertoire, including the villainous Claggart in Billy Budd, Arkel in Pelléas et Mélisande, Judge Turpin in Sweeney Todd, Fiesco in Simon Boccanegra, Gremin in Eugene Onegin, Geronte di Ravoir in Manon Lescaut, Trulove in The Rake’s Progress, Pogner in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, and Fafner in Siegfried, a role he’s set to reprise in concert with the London Philharmonic in 2020.

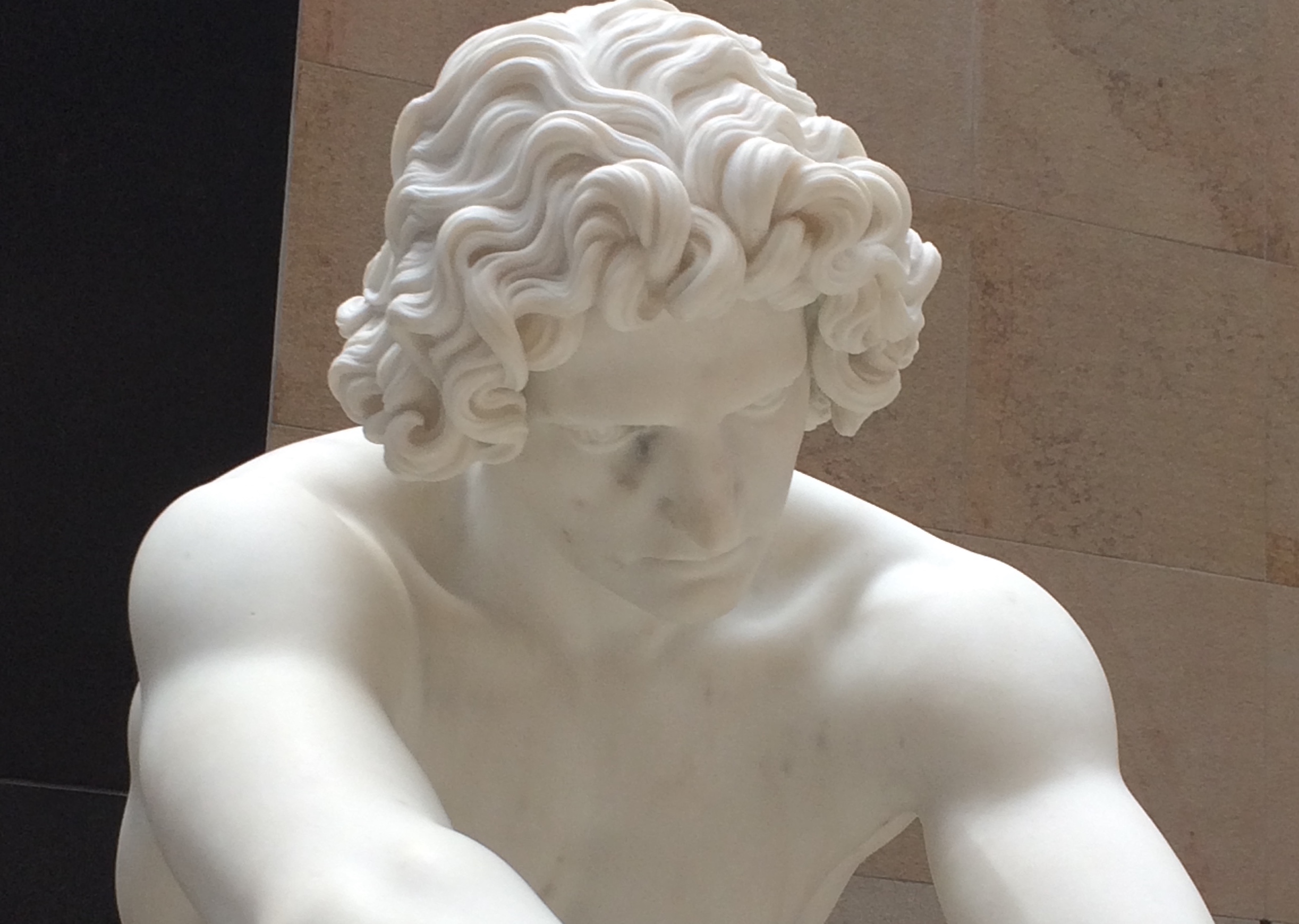

Currently Sherratt is performing as Sarastro, in a Barbe & Doucet production of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) at the Glyndebourne Festival, a venue in which he’s performed frequently over the years; he appeared in both Der Rosenkavalier (as Baron Ochs) and Pelléas et Mélisande (as Arkel) there last summer. In the autumn, he’s scheduled to sing the role of the ghostly Commendatore in Don Giovanni at Royal Opera House Covent Garden. In our recent wide-ranging chat, he shared fascinating insights on the distinct joys of Mozart, Mussorgsky, and Strauss, the differences performing in big and small houses, and the ways he’s kept his in voice in tip-top shape. Sherratt is also, it must be noted, one of the most down-to-earth people I’ve had the pleasure of speaking with, which makes his brewing onstage presence all the more fascinating.

How are things in Glyndebourne?

It’s fifteen minutes away from my house, so it’s a local gig for me. We’ve only lived down here five years, even before then it was always my favorite place to work, because it feels like family. The setting is amazing, and I’ve been in good productions. The house is the perfect size; it’s not too big. You don’t feel you need to shout your head off the whole time. The acoustic is great. And, I know everybody. It feels like home.

You recently marked your 100th performance as Sarastro. A lot of singers I talk to say Mozart is like a massage for the voice.

It is. Precisely. If I can sing Sarastro well, with legato and simply – not signing loud – if I can do this, then I know I’m in good shape. Because at my age and everything, you can just end up doing loud all the time.

It’s what a lot of basses do.

Yes but Mozart is really a balm for my voice, and good discipline too. People might think, “Oh, it’s just another Sarastro” – no. If you want to do it well, with really good line, and make it beautiful, then you have to offer something else. It can take me a couple weeks just to pare things down a bit – you don’t have to bellow; it’s just brushing through voice. We’ve done a few shows now. I haven’t really sang anything lately; after Billy Budd (as John Claggart) I took a month off for holidays, and then I did (Die Zauberflöte),. Now my voice feels in the best shape it’s felt for ages, fresh and bubbly. I keep thinking, “Oh, this is nice!”

The 2019 Glyndebourne production of Die Zauberflöte. (Photo: Bill Cooper)

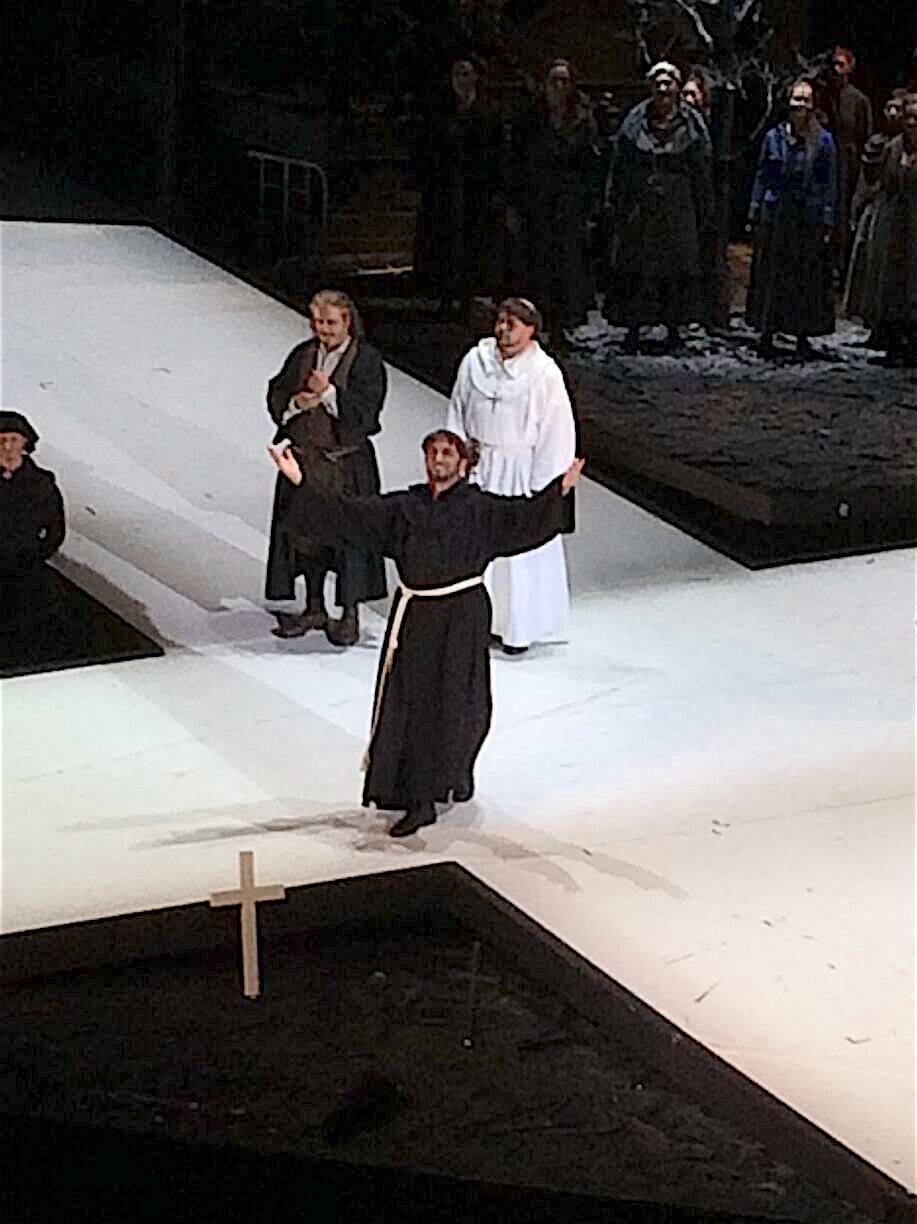

I spoke with Barbe and Doucet about the production, and they agreed there’s a fun element to the opera, but they were keen to bring this interesting feminist history into it, which is interesting. Have you worked with them before?

No never, but you know it’s really interesting how they superimpose this story about the Sacher Hotel and Escoffier and such. It’s clever what they’ve done.

You had done this role earlier this year, in English, with the English National Opera.

You know my career started late – I started when I was about 36, 37, so I had to squeeze an awful lot in the last ten or fifteen years, and I did my first Sarastro at the ENO in 2004, and I learned that translation, but what was distressing and surprising was the fact it was a whole new translation this time, and I couldn’t get this new one in my head. I kept coming out with great chunks of the old one, which was funny and a bit alarming for everybody in the cast. I’d done that production, by (Simon) McBurney, twice before. I remember him saying in rehearsals, “Remember, Mozart was a genius, but Schikaneder wasn’t!” Sarastro is so difficult to play – there’s no journey. Whatever production (of Die Zauberflöte) I’m in, I bring my own human approach to the role.

Gennady Rozhdestvensky conducting his final concert in Japan, 2017. (via)

You’re also set to perform as Pimen (in Boris Godunov) at Bayerisches Staatsoper next year.

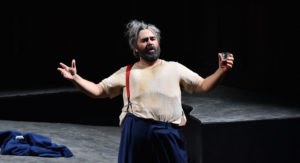

I’ve sung (the role) three times now. It’s amazing music, I love it; Mussorgsky gives you lots of time and space as a singer. The first time I did it years ago was in English, in a new production with Ed Gardner at the ENO. In a way it was good for me; I got to know the measure of the part, and in my own language. The next time I did it in Russian, and it was with an entire cast of Russians, with Rozhdestvensky conducting, and that was terrifying. Oh my God! It was sheer luck I did my first one in Russian with him – honestly, just terrifying! At the end of the first week, he said, “Can I say to you, Pimen has 888 words and 868 of yours are really great.” And he also said, “I love you as an artist.” That was the first positive thing anybody had said to me all week, and I thought, “Well! I’m okay then!”

I was scheduled to sing (Pimen) in Munich back in 2014; after about day four of rehearsal, my throat started to feel strange, and I thought, “What’s this?!” Then my voice went… boom. The day before the sitzprobe I really could barely speak and I thought, “Oh, not now!” – and that was to be my debut in Munich. And the next day I couldn’t sing a note – not a note. I went to see the voice guy and he said, “I think you’re coming down with something. You won’t be singing it first night, everything is congested.” So I went home, because the next show was five days or so later. I never went back. I had such terrible bronchitis, and I couldn’t sing a note. So that was an abortive debut. They asked me to do it again in 2017 and I was busy, so this is the third time lucky – I get to do Pimen in Munich, finally!

Brindley Sherratt as Sarastro in the 2019 Glyndebourne Festival production of Die Zauberflote. (Photo: Bill Cooper)

I was speaking with a singer recently who noted the differences between big and small houses, and the aspects of singing in each of them. There is this assumption that because you’re a bass you can just sing loud.

I sort of feel Glyndebourne is wonderful that way – because, for instance, I did Billy Budd about five or six years ago in there, and I don’t like doing loud roles in a house that size. If I’m going to do big music, I like a big house; you can just chuck your voice out there. There is always a feeling in a smaller house that it’s a bit much. But with the big house, for me it’s about clarity, not the amount of muscle you put on it. I’ve been in rehearsal with voices and thought, “Wow, the room is shaking here,” but onstage it’s a different ball game because it’s just the clarity that makes you carry over in the big house. I’m slowly learning.

When I started to do bigger roles in the opera house the feedback was, “Oh, your voice isn’t big enough for the house,” so I tried singing everything really, really loud, and my voice got too heavy, too thick, and I lost the top, so I went back to the drawing board and thought, “No, I don’t want to go this route, I’ll have a short career,” so I reworked, things, kept the vocalise going, and tried to keep as much sound in the head as I can. If I listen to people I admire, like Furlanetto. At 69 his voice has so much ring on it. He sings huge, but it’s beautiful, and that’s my goal: I want to make it clear, and so that it means something rather than just standing there like, “Listen to me!”

You’ll be going back to The Met – a very big house indeed – a few times next season, doing Bartolo in Le nozze di Figaro.

They said, “Come do Bartolo” and I thought, it’s nine performances in a month – yes, I’ll do that, and I do like being in NYC. When you go onstage and see the space, you think, “Oh I’ve really got to honk!” Now I realize it’s more about the ping on your voice than anything else. You’ve got to keep it clear, then you’re fine.

Brindley Sherratt in rehearsal for the 2019 Glyndebourne Festival production of Die Zauberflöte. Photo: Richard Hubert Smith © Glyndebourne Productions Ltd.

Like we said, Mozart is a good massage for the voice. But you mentioned something a while ago about the importance of coaching…

I was chatting to Gerry Finley at the time, saying, “I’m not singing right, I’m not happy with this” and he said, “Go see Gary (Coward) for a few sessions.” Gary was a singer in the chorus in the ENO for years. I sang a few things for him and he said, “There’s nothing wrong at all, you just got a bit thick and heavy,” so he prescribed some vocalise – singing just over the middle of the voice, never singing loud, and I just worked that into my routine, and I got it back, and I sang the St. Matthew Passion arias, and a lot of Handel. I still do, just to keep the flexibility going and the voice moving. I’ve noticed it, certainly with basses: there’s this assumption you don’t need to warm up that much. But I do quite a bit – I can’t abide going out there and just “AHHH!” I want to still be able to sing the Matthew Passion arias. That’s what I did to get my voice back on track. Just to keep the head voice going, and the flexibility.

Yours is a very flexible voice; it’s one of the things I noticed first in hearing you.

My voice just gets into this “uhhhhh” rut if i don’t do it. I did Ochs (from Der Rosenkavalier) at Glyndebourne, and that was a role where people said, “You’re not an Ochs! You’re the wrong voice; you’re the wrong shape” – but you know that (role) really helped my voice hugely, because it’s all moving around, it goes up to F-sharp and down to C. That was a period when I was singing the best I’ve ever sung; everything had to be there every night and it was, vocally. It was almost like Mozart, really. I said to my agent, “I want to do this a lot, while I still can.” It’s nice to have that fun on stage. John Tomlinson said to me, “Do as many Ochs as you can – do the happy roles, the fun roles; that way you can sing them all again when you get old, because you won’t be stuck with low stuff, stuck in one position. ” Use the whole voice, up and down; that’s really important to me.

What about lied?

Tomorrow I’ve got an afternoon with Julius Drake. He came, bizarrely, to Billy Budd and the Ring I did, and Alice Coote – she’s an old friend – had said to him, “Hey, work with Brindley” so he said to me recently, “Come to my house and we’ll spend an afternoon going through stuff.” I said, “I was a choral singer for fifteen years, then went straight into opera, so lied is not that much of my knowledge and experience.” He said, “For two hours we’ll try a load of stuff.” I did do “Songs And Dances Of Death” with orchestra a few years ago, and I did Strauss songs with orchestra. If I can find the right color and the right song, then I would love to do more of it. To sing in a more intimate setting I need somebody skilled at it, who knows me, then we can work out what’s best for my color. It’s like going back to school, like, “Let’s start with a blank page.” And I have a dream: I want to do Winterreise. I’m not known as a recital singer, but I’d like to get that going.