Photo: Kevan Bamforth

“What’s the c-word?” I ask my students.

“Context!” they reply.

It behoves any writer to know something about the subject to which they profess passion, love, adoration. Far from being antithetical to the spirit of discovery, context tends to enhance appreciation, understanding, and overall enjoyment, while leaving room for questions: why is a musical phrase Beethoven’s 5th done a certain way by Carlos Kleiber, but not by Klemperer? How much should the tempo in the final movement of Das Lied von der Erde be guided by text, or might there be another approach (and if so, what)? How do the alliterative sounds of Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s writing inform the aural sounds of Strauss? What roads led to Wagner’s famous lack of resolution in Tristan und Isolde and what paths led out of it (what didn’t, really)? Some things have definitive answers, but in art as much as life, some things tend to be –must be – evolving conversations.

It’s good to be reminded of the importance of both definition and evolution, even while striving, amidst quotidian mundanities (the continual handwashing, the ever-growing pile of ironing, the nightly nod-off on the sofa) for something that can be felt and experienced beyond the immediate. Around the world culture lovers are largely in situ; the only travel many are able to do is through one’s own imaginings. How rich they truly can be when one has the brushes and the pigments at hand to shape the many flat, smooth surfaces of weeks and months before us, but oh, how difficult it can be to find the inspiration to start, let alone to continue. I tangle, on any given day, with threads that pull in all directions: emails, updates, cooking, correcting, battling seemingly-endless streams of dust. But something within persists, and has done to varying degrees since the pandemic began, a constant akin to Malevich’s infamous black square, which resonates, reverberates, swallows, enfolds, encompasses, and even (especially) enlightens. As I wrote at the end of April, curiosity has been the guiding light through not only the current COVID19 era, but more broadly, a music education sorely lacking in proper guidance through childhood and youth, but one which has enjoyed a lovely Renaissance in the last few years. In an editorial for Opera Canada magazine earlier this year I revealed my strong belief in studying prior to attending (or now, livestreaming) events; that belief extends to listening. I find it stressful to put on a piece of music and not know even a little bit about what I’m hearing, let alone something about the artists involved, its history of composition, and the various approaches to interpretation. The work of Edward Seckerson has been invaluable in this regard; context and curiosity join in important ways through his work, allowing for new insights, deeper questions, and ever more bundles of curiosity.

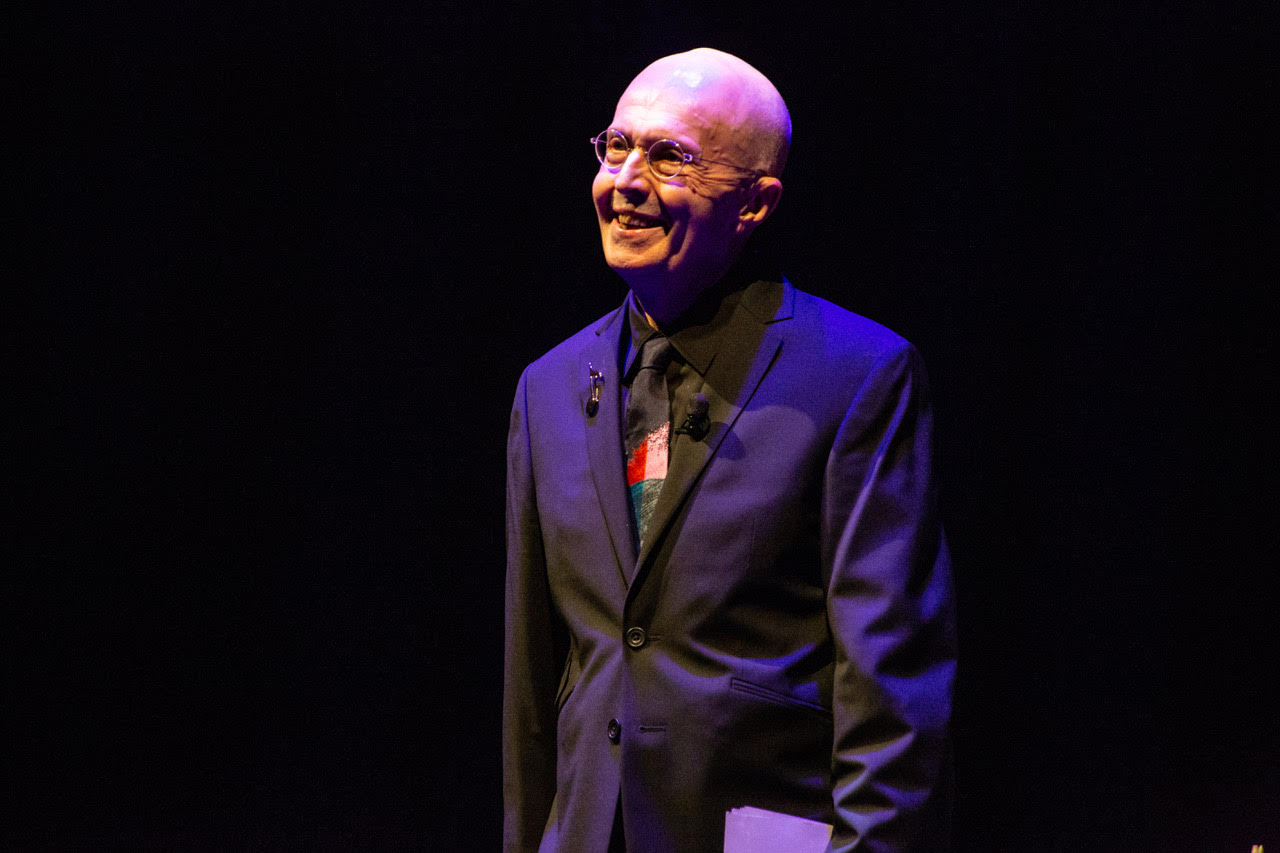

A self-described “writer, broadcaster, podcaster, and Musical Theatre obsessive,” I discovered Seckerson’s work via his regular reviews for Gramophone magazine. His smart, accessible, well-observed writing employs poetic if equally clear language; the Gramophone review of the Pentatone/Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester release of Das Lied von der Erde from earlier this year, for instance, mixes the text of Mahler’s grand work and its recorded history with keen musical and vocal observations, contextualizing and poeticizing in one sublime whole. Along with working in formal media for various British papers through the years (in the role of critic), Seckerson has worked in theatre and music, appearing onstage in various forms and roles. Writer and host of the long-running BBC 3 Radio series Stage & Screen, he is and has been a regular on radio and television, and has contributed commentary for the Cardiff Singer Of The World competition regularly. As well as penning books on Mahler and conductor Michael Tilson-Thomas, Seckerson has also been part of stage works exploring the life and works of composer Richard Rodgers and conductor Leonard Bernstein. Despite (or perhaps owing to) such accomplishments, Seckerson does not think of himself as press these days so much as a figure who, as he puts it, wants to be (nay, is) part of a broader creative conversation. Indeed, conversation is the thing he positively excels at; Seckerson has interviewed many, many people, including, as his website says, “everyone from Bernstein to Liza Minnelli, Paul McCartney to Pavarotti, and Julie Andrews to Andrew Lloyd Webber.” His interviewee list is a who’s who of figures from the classical music, theatre, and musical theatre worlds, reflecting his passion for all of them, and, more broadly, his commitment to the intelligent exploration of culture in all its facets and forms. Such a gift for (and active commitment to) one-on-one conversation is truly a rarity in a world of pre-written Q&As and preening Insta-videos. I was fortunate to be able to experience this gift live earlier this year, during a talk at London’s Bishopsgate Institute featuring Sir Antonio Pappano; over the course of the evening I was struck by his casual balance of personal and profound, funny and foundational; attending a Seckerson talk means one will learn as much about humanity and artistry (and the sometime-connections therein) as about the actual figure themselves, no small thing in a world where image tends to trump authenticity.

Seckerson has put his distinct talent for conversation to work via a regular chat series produced over the course of the lockdown. Guests so far have included conductor Edward Gardner, violinist Nicola Benedetti, actor/singer Julian Ovenden, and mezzo-soprano Dame Sarah Connelly. Conversations span from thirty to sixty minutes and, as he explains, are entirely unedited, and are inviting exchanges which nicely embrace both the macro and the micro aspects of individual artistry and creative development, particularly within the context of our current pandemic era. His casual remark to violinist Nicola Benedetti during their conversation in June, that Elgar’s Violin Concerto (the performance of which was one of the final performances he attended in London before lockdown) is “the most intimate of epics”, inspired a spontaneous and enthusiastic response from the violinist (“It’s an amalgam of the very public and the very private Elgar”, he went on to explain), the warmth of which fuelled their lively almost-30-minute exchange. In a time when one’s spirit can so easily be dragged down by a multitude of daily mundanities, when life can feel so cold, empty, and robbed of joy, such sincere exchanges feel like a needed blanket of warmth and goodness.

Writing about another writer one happens to admire is no easy task; writing about a writer who is also a gifted conversationalist and who, octopus-like, has many arms in many different and fascinating worlds and is, quite simply, so very genuine, is indeed a rare gift. Perhaps my students, when asked what the c-word is, might also now respond loudly with, “Conversation! Commitment! Curiosity!” – for these are things Seckerson’s work has encouraged in my own pursuits, particularly through these many gloomy months. We spoke in August, before much of the programming now underway in London was announced.

Photo: Edward Seckerson

How have things been for you through the lockdown?

I live in central London, and it’s disturbing that the West End, and London overall, has been so empty – so many businesses are going to close. The Chancellor introduced a supplementary package for eating out Monday to Wednesday; it’s done the trick, and a lot of people are eating out as a result – they get £10 off their meal. In terms of the arts, people here are so desperate to get things moving again – they’re being so resourceful and creative. It isn’t always successful, but the will is there, and that’s important.

Have you had time to reflect on your work during this time?

Well, one of the things I suppose I learnt over the years of reviewing – and of course I still review for Gramophone – is that I always feel, just as I did when I was writing for The Independent, there is really no point offering your subjective view. Everything is subjective! But it’s best to offer some sort of insight into the piece you’re reviewing. I wrote a review this morning for Gramophone of the new Dudamel recording of the Ives symphonies, and I spent most of the review really talking about the music, because that, to me, is more important than just registering whether we have another successful performance on our hands, or what the merits or otherwise are of this performance. I think it really is important to give some kind of guide to the piece you’re reviewing, and the same is true of when I do the comparative reviews on (BBC) Radio 3, on Record Review – I think it’s important to offer people some kind of road map to the piece as well as interpretations.

That map, for those who don’t have a formal degree in music, is very helpful; it feels like a door swinging open, which isn’t always the case with classical music writing. Is that your intention?

Yes, that’s exactly my intention, to make that map clear. I always say that it’s almost irrelevant whether Ed Seckerson thinks a performance is special or not; what is important is that I offer some kind of sense of the experience, the shared experience if you’re reviewing something live. People who weren’t there want to know what it was like to be there, so there’s that element. I used to get a lot of flak when I reviewed opera for The Independent; people would say I spend too much time discussing the production and not enough time discussing the relative merits of the cast and their performances, but since most of those reviews were about new productions to me it was important to try and express, or offer, some kind of insight into what I think the director was looking for.

I’ve received similar feedback, that I focus too much on the ideas of the director and theatre aspects overall, and not enough on the singing, but I read your review of Barrie Kosky’s infamously divisive staging of Carmen and it gave a real sense of why he chose what he did, contextualized within the history of this very famous opera.

… and that’s the point. I think there are a lot of spectators out there who simply want their opinion to be endorsed or otherwise when they go to the opera – (like) if their favorite singer is singing, they want to see a rave about them. But it is actually important to discuss how the piece is being reimagined. Opera would very quickly become a museum culture if people didn’t keep reimagining the pieces, and sometimes they do so with limited success, sometimes they do so with hugely insightful success, and I think that’s important. One of the reasons why I’m successful as a critic is because I was an actor, and I have a very real sense of what it’s like to be on a stage and be that vulnerable – but also, if a director makes a choice, I feel it’s important to be able to ask, if it’s not immediately clear, why he or she has made that choice, to be able to offer some kind of suggestion or insight as to why they might’ve made that choice. And I don’t think audiences question that side enough. One of the reasons it took so long for slightly more, shall we say, radical theatrical productions to become the norm was because audiences weren’t prepared to do some of the work themselves. And I think it’s important that audiences are not passive, even if it’s a concert. I’ve spoken to so many musicians who say they know immediately when an audience is listening in a certain way; if an audience isn’t listening in a certain way, or there isn’t that connection, they know immediately that that performance won’t succeed, or won’t succeed on the level they might’ve hoped.

Musician friends of mine have noted how the quality of the listening can change dramatically according to where they perform; geography makes a difference.

That’s because certain audiences are experiencing a different culture of music, sometimes for the first time, so they might listen more intently.

Or not…

That’s true! We do take a lot for granted here; we are very spoiled in cities like London, which is surely a music capital of the world. The choice, on a daily basis, when there isn’t a pandemic, is absolutely extraordinary, and you know, this time has made me appreciate what live music really means to me.

Backstage with Dame Diana Rigg at Queen Elizabeth Hall, March 2019.

What has changed in the quality of your listening as you stepped away from reviewing?

Well, one of the pleasures of giving up writing newspaper reviews was that I could actually go and sit, relax and participate as an audience member, which gave me, and still gives me, great joy. You do listen differently when you are writing about something. I still listen in great detail but I think part of your brain is already forming the sentences, is already thinking of images, for the review you’re going to write, which is an intrusion. I first wrote for The Guardian in the days when pretty much all the reviews were overnight reviews, and I was never so unhappy as I was at that time as a journalist. I did it because it was a big break for me and it was establishing my name, but I hated every minute of it, and when I joined The Independent, the first thing I said to Thomas Sutcliffe, the arts editor, was, “If you’re doing overnight reviews, I’m not in the business of writing them” and he said, “No, I want people to sleep on what they’ve experienced and get up the next morning having digested and let it sit for a while.” All this nonsense about rushing out to meet the 11pm deadline doesn’t help anybody.

A long time ago there was an arts editor I worked with, and (Placido) Domingo was in town doing a revival, yet another, of the (Franco) Zeffirelli Tosca, it was Gwyneth Jones and Domingo, and the editor said, “We want an overnight review because it’s Domingo” and I said, “The show comes down at twenty minutes to 11pm; there are two intervals in the production; your deadline is 11pm; it’s impossible” and the editor said, “Well you’re no use to me as an opera critic if you can’t deliver a review after the show.” I said, “When will I do it?” He said, “You write during the intervals.” I said, “How can I write organically about a performance when it’s only a third of the way through? Oh, but wait, I have a good idea: why don’t I write the review before the performance?” It took him a moment or two to realize what I was actually, rather savagely, saying. And I did write the review, and I basically had to cheat it and write at the intervals, so there was no coherence. That is the kind of attitude that existed in media then and it still does, but thankfully some things have changed.

Some things have changed, but some have not, that attitude has transferred over to an obsession with clicks and views; Antonio Pappano and I spoke about it earlier in the summer and he said at one point, “if that’s what we rely on, we’re lost.”

When I did my talk with Pappano – you were there – at Bishopsgate earlier this year, we spoke backstage about the new culture of journalism, actually. You know, I was in at the start of this (change) – I was a mainstream classical reviewer in the days of broadsheet papers as well as this transition online, and indeed I remember people I knew at Glyndebourne, when the online thing started to happen, saying to me, “What are we going to do about inviting people?” I said, “You have to make value judgments about the kinds of writers you’re inviting – ignore all this business about how many clicks and hits they get, and just read what they write; read the work, and decide who you think is worth inviting.” It’s that difficult, and it’s that simple. And so when we spoke in January, Pappano himself was horrified I couldn’t get arrested at the ROH these days. I said, “It’s not because I’m writing reviews; I’m honest about that. It’s because I want to be part of the argument; I want to be part of the debate about the kind of work that’s being done at the ROH.” I mean, I’d be quite happy to attend rehearsals, but the attitude is always, “Oh no, you’re a member of the press! You can’t!” and I’ve said, “But I’m not a member of the press anymore, I’m just me…!”

This sounds frustratingly familiar.

It’s so frustrating. If I go to a dress rehearsal and I want to make some constructive comments, I won’t write a review, I want to be part of the debate before or after the performance. But I can’t contribute anything if I wasn’t there.

You’ve still really crossed over from the media world. What has that process been like?

It’s been very interesting. Long before I wrote for The Guardian or The Independent I was invited to ENO, during the Sir Mark Elder/David Pountney regime, and I got invited because the Press Officer was enlightened enough to know my background. I was making in-roads as a journalist and writer but had come from the theatre, and I had a musical background as well, but I had come from the theatre directly and they had the good sense to invite me long before I was writing reviews – so I had points of reference. When I did start writing reviews, I’d been there, watching these shows, seeing this company develop, which fed into the kind of writing I produced, which fed into the things I did when I started writing for a major paper.

So you paid your dues, just not in the usual way… ?

I paid my dues, though yes, my background is very unusual for a music journalist, because although I studied music when I was young – I was saying this in the interview I did recently with Nicola Benedetti – my problem was when I started learning the piano at a young age was that my musicality had already exceeded what I was capable of doing on the instrument, and I found it hugely frustrating. Nicola completely identified with that, by the way! I said, unless I started even earlier – and that battle that goes on between technique and musicality is huge.

When I was learning piano as a child, musicality was something others tried to forcibly extricate; there was an intense focus on technique instead, which I was never very good at. Musicality was perceived as being unfocused, sloppy, pointless.

How awful! I mean, I went to a comprehensive school where they had peripatetic music teachers, and I was handed a violin one day and learned my way around that instrument without much success, but at least I knew my way around it. I took up percussion, which was a way of producing more instant results. I could read music and rhythm, and picking up the technique was relatively uncomplicated compared to learning the violin, so I was able to play with amateur orchestras and youth orchestras, and that was another way in. But this thing about musicality, coming as I do from a theatre and music background, I was brought up to believe rather as Leonard Bernstein said, to just embrace music in all its facets, in all its styles – that’s the way I was brought up. I was never directed toward “good” music or “serious” music, I was just encouraged to enjoy music, period, and lucky enough to be taken to theatre and musicals and concerts, and that’s where it all started to marinate. Many of my colleagues come from more academic backgrounds. I always say, nothing wrong with that at all, but if you’re going to be a critic, and a lot of young students have often asked me about this – “What is the route in? What is the way in?” – I’ve always said, there isn’t any particular way in, it’s a case of just doing it.

This is precisely the advice I give my own students: do it, do it a lot, but be wary of doing it for parties who will exploit your talent and energies.

Precisely. I started years ago, by producing dummy reviews and sending them to people, because I was an avid record collector as a boy, and as I grew up I became more and more fascinated by interpretation, and that, to me, was where the music-making really started to happen. So I always say to people, it’s not so much what you know, it’s what you feel. And if you can’t recognize when an artist makes a beautiful phrase, then you’ve no business doing the job. It’s about having a musicality which chimes with what the artists themselves are doing. And you have to feel confidence in that. The one thing I am confident about amongst all my insecurities: I am completely confident about my musicality.

That confidence translates to your online conversations. Why did you start this series?

When lockdown happened, my partner said to me, “Why don’t you do audio?” I said, “Honestly, do I really want to do audio? And not earn a penny?! Surely I should be looking for ways to earn a bob or two during this period!” And my partner said, “It’s important you’re out there and doing what you do.” So I decided to do a series with people that I had some kind of association with, either we’ve crossed paths or I knew their work or they knew my work. Nicola was the exception – I had never met her, but one of the last concerts I went to this year was her live performance of the Elgar violin concerto at the Royal Festival Hall; I was blown away by it and thought it was a good reason to speak to her, since the related album was coming out.

But basically what I wanted to do was to talk to people that would feel comfortable relaxing on a remote audio with me, and were prepared to do so without editing. These audios are all unedited, they are completely spontaneous – this was important to me; sometimes a doorbell rings or whatever, but basically I’ve said to these artists, “I want this to be raw, as if we’re doing this live.” And I was determined we should mix classical and musical theatre, because they are my two main areas. I started with John Wilson – I bumped into him literally in the first week of lockdown, he’d moved around the Tate Modern, and I was walking down the Embankment, and there he was. We stood in socially-distance conversation for a while, and I said, “Hey do you want to this?” and he said “Sure!” What I decided now is to continue to do them. I think as a writer you have to get past … look, this is tricky, but you have to get past the idea that you do this only professionally for a living; sometimes you should do things occasionally for the hell of it. That was a difficult pill to swallow at first; I felt I was putting a lot of effort in for no return, and as a freelancer that’s a no-no. When I think back now to the kinds of jobs I would turn down routinely, I would be quite grateful for them now.

Engaging in freebie culture is something I caution my students against. When it’s you calling the shots, it’s a different energy; you have all the control. That’s different than giving everything away to an organization who will exploit your talent for their numbers.

Exactly! Several have said to me, “You should charge for these interviews” and I said, “But this is my product; I have total control over it.” It’s been quite refreshing to go to people with my reputation and history and just say, “Hey, do you want to do this?” Generally speaking they’re only too pleased, especially during this time, but I think they’ll be pleased after this crisis is past, so long as I can supplement it from other paid jobs; most of my work consists of live conversation events at festivals or the like; Bishopsgate was an experiment. I lost a huge amount of work when the pandemic struck, including live interviews with Dame Janet Baker, an evening with Petula Clark at the Theatre Royal Haymarket, and many bookings with Patricia Routledge, who I’ve been working with for years in a show called Facing The Music, about her musical theatre career. Those things are where the money for me is. Writing, broadcasting, the BBC fees have gone down and down… you have to move with the times, and reinvent yourself. I reinvented myself hugely, because as an ex-actor, I loved the buzz of being onstage and still do, albeit in a different capacity.

Backstage with Claude-Michel Schönberg at Bridge Theatre, February 2019.

I was in theatre also and I do miss it, though I find performance and authenticity now tend to meet through writing; do you find this in your pursuits?

Oh yes – and these audio interviews, I hope, are something that shows the best of what I do. I think good interviewers are few and far between; let’s focus on the people who can initiate a conversation as opposed to doing a Q&A. I hate those. People say “Will you do a Q&A?” and I say, “No, I’ll do a real conversation.”

The reciprocity of a real conversation demands sincerity, which seems like a rare commodity these days.

It is – and I’ve met and spoken with a huge cross-section of people, in various capacities. I was a mainstream presenter on (BBC) Radio 3 for some years, I used to do the breakfast show on the weekends and had a show called Stage & Screen, which ran for six years and was devoted to musical theatre. I learned a lot on that show and had a great time. We met an awful lot of luminaries from the world of musical theatre, and I learned a lot about sitting down and conversing with people.

That’s what radio teaches one: the importance of give and take.

It’s a huge thing. You know in the first few minutes of talking to someone who’s done x number of interviews with people if it’ll work. I interviewed Glenn Close for Sunset Boulevard at the Coliseum; they didn’t want to put her in front of the press corps, it was done with me interviewing her rather than people shouting out questions. I did a video interview just before that for the website and I remember, it was so obvious, she sat down like, “Oh here we go, another interview” – as a film star she would have done twenty-five or more in a day to promote a film – but the first thing I wanted to talk about was the Richard Rodgers musical Rex she’d been in when she was unknown. I was just curious about that; Nicol Williamson had been in it also And she looked visibly stunned when I brought this production up. The whole interview changed direction the minute she knew that I knew what I was talking about, that I wasn’t another hack. But I’m afraid in some quarters, in the theatre and movie world, it’s par for the course. The level of ignorance among so-called journalists is breathtaking – and yes, the sheer laziness, the total lack of research. People you talk to, they want to know that you respect the work they do, it’s only natural, you sometimes have to talk with people in rotten moods, but the minute you turn it around and say, “What I thought was interesting about your performance was this and this and this… ” – it changes everything.

Good interviews demand many things: research, listening, reciprocity – all while holding one’s own. Lately it feels as if these things have been disposed of via online culture…

… oh, this whole business of so-called “influencers” is driving me absolutely nuts! It’s about nothing at all; it’s just so much noise around people who appeal to the lowest common denominator and who generate a following. Suddenly they’re endorsing various things…

… and some are being invited to things or cast based on their social media presences. I wrote about Instagram as it relates to opera casting in 2018, but the pandemic seems to have underlined that growing connection.

It’s worse in the musical theatre world too – it’s a different kind of celebrity. There is Instagram casting in that world; I’ve spoken to producers who have engaged in it. When I did my stage conversation last year with Patti Lupone I brought this up and she was mortified by the whole thing. It’s this whole box-ticking thing…

Backstage with Patti LuPone at Theatre Royal Haymarket, March 2019.

“This person has x number of followers” – even if they bought them – “this person gets x number of views on their videos” – those are easy to fake – “this person gets lots of engagement” – how many of them are genuine? – “this person has a cool/sexy image” – which is all photo filters…

Indeed, but there’s also the basic question: can (the artist) actually do the job? Live and onstage? Are they the best person for the role? Or are they being cast because they have six million followers on Instagram? It’s a serious problem. Producers want to sell tickets obviously, and Intendants want to sell their opera houses, but if we’re not very careful, it could derail the integrity of the business. It really could. I participate in social media because I like to think of myself as savvy when it comes to online, but I don’t exploit it as much as I could; I am very suspicious of it. And I think unfortunately, the first question you’re always asked – and you probably experienced this yourself – you go to someone who doesn’t know your work, and you say, “May I do this?” and they say, “How many hits does your website get?” I mean… many of the people working in the business now are so young and they have no history or knowledge of the people or the history of people like you and me. And I’m not saying that in a boastful way; I’m saying it because it’s a fact. I get the most insane emails sometimes asking me to cover things that have absolutely nothing to do with my area of operation or expertise. I’m on a press list somewhere and so…!

Very often I get questions about my metrics too, and my response is that my numbers aren’t The New York Times, but they don’t have to be; my readership is faithful.

Exactly, and that’s the point! I mean social media is famous for endorsing things so you put something up with all your powers and people who know you in the business will like it, and click on the button, but how many listen to the interview the whole way through, or read the whole feature to the end? Of course I know people read Gramophone magazine – they read it from cover to cover, it’s the only serious record magazine left, which is why I still write for it – but I’m delighted some of my audio interviews have hit the spot for listeners. I know people who’ve listened to them and I know the pleasure they’ve got from them, which is far more important than reaching 50,000 people who don’t listen to more than a couple minutes. I will say, I didn’t want to do a series on the lockdown or the problems (of the music industry) associated with the pandemic; important though it is to talk about these things, that’s not what I’m in the business of doing. I wanted to stay talking about the music.

Speaking of music, Sarah Connolly’s relating the text of Das Lied von der Erde to Bach in your chat made me rethink that piece, but then, isn’t that the point of good conversation – to inspire one to think about things in new ways?

I agree with you entirely – but of course you’re only as good as the quality of your interviewee; this is where one has to be selective. I know why I chose the people I chose. And Sarah is a rare bird, not only a wonderful talent, but I’m probably more pleased with that one than the others so far, she’s such a great talker: engaging, amusing, smart, all those things.

Her trust in you seems palpable.

That’s where the history comes in. With some people it takes a long time to earn their trust; for instance, with Patricia Routledge, it took a long time before I earned her trust. She’s someone who’s lived on her own, who has huge integrity as an actor, but my goodness, it was worth the wait. When there is mutual trust, it frees you up, and it’s lovely for me when one’s reputation precedes one and someone is happy to do something simply because they trust you. We both know we’re going to have a reasonably stimulating exchange and I’ll not be talking about non-musical things as others might, that I’m there for the music. At the end of the day the music is what it’s all about, and that’s what I’ve adopted as my yardstick over the years.

In conversation with Patricia Routledge at Theatre Royal Haymarket, part of Seckerson’s “Facing The Music” series with the British artist. Photo: Danny With A Camera