There’s plenty going on in both the orchestral and opera worlds right now. Everyone is busy – including yours truly – and feeling somewhat worn-down, but it seems important, amidst the chaos and concomitant tiredness, to keep interested, inspired, and reminded of the existence of good things and people, and to make the effort to recognize accordingly. It matters more than ever.

Thank you Ozawa!

The Japanese conductor, whose passing was announced this past Friday, was truly a powerhouse of passion for music, in all its expressions. My formal obituary for The Globe and Mail is here (paywall).

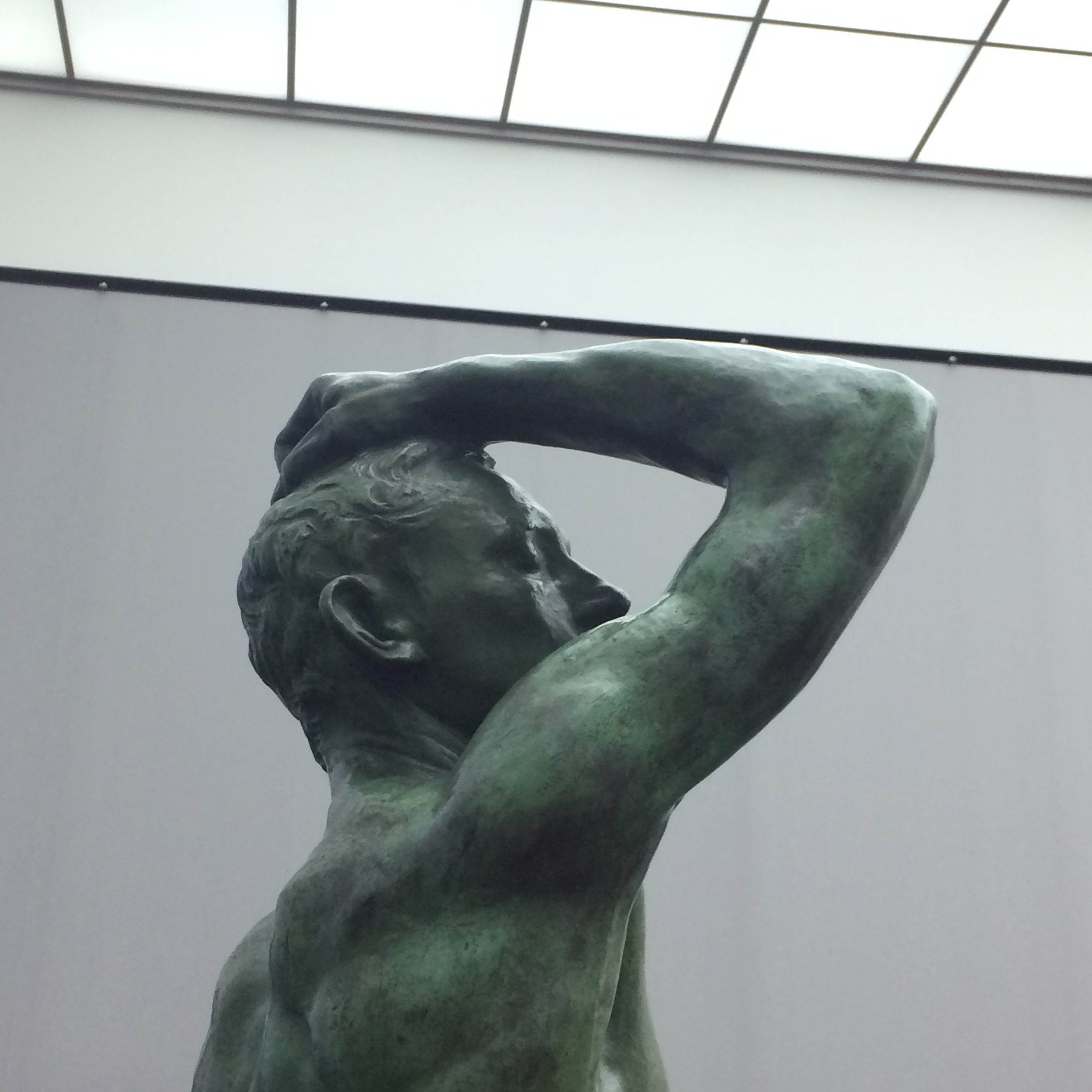

Ozawa truly changed the centre of classical gravity and the way it was perceived more broadly, by the public and aspiring musicians. “It’s hard to be a pioneer, but he did it with grace,” noted cellist Yo-Yo Ma in a moving video clip released by the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO). Ozawa was the organization’s very long-serving Music Director (1973-2002) and was known as much for his dynamic performances as for his love of the Red Sox. He was also committed to music education, particularly in his later years. Well before his time in Boston, Ozawa was Music Director of the Toronto Symphony orchestra, and led the orchestra in the opening of City Hall in 1965. My music-mad mother recalled seeing Ozawa and the TSO at their then-regular digs (Massey Hall) many times and I clearly remember how she praised the maestro’s attention to detail and expressive physicality; she also noted the famous mop of hair, like so many.

Hair aside, Ozawa had a sizeable live performance track record and an immense discography, although he wasn’t quite so well-known for his opera as for orchestral renderings, coming late (as he admitted) to the opera world. Still, everyone has favourites, and some of my own Ozawa treasures include opera, among them Messiaen’s Saint Françoise d’Assise, which Ozawa premiered at Opéra national de Paris in 1983 (at the composer’s personal request); Krenek’s Jonny spielt auf, presented at Wiener Staatsoper in 2002 (when Ozawa was their Music Director); and Stravinsky’s opera-oratorio Oedipus, from the Saito Kinen Festival in 1992, the same year Ozawa co-created the festival and related orchestra. The poetic production featured Philip Langridge and Jessye Norman in a Japanese-influenced staging by Julie Taymor.

Speaking of Oedipus…

Update 18 February: The planned production of Jocasta’s Line (information below) has changed. Director/choreographer Wayne McGregor and actor Ben Whishaw have had to withdraw from the project. Now called Oedipus Rex/Antigone, the work will be directed by Mart van Berckel and Nanine Linning, respectively. Moussa’s Antigone is a co-commission with the annual Québécois Festival de Lanaudière.

Original: Actor Ben Whishaw is set to appear as the Speaker in an intriguing new presentation of the work to be presented next month at Dutch National Opera. Called Jocasta’s Line, Stravinsky is here being paired with 2023’s Antigone by Canadian composer Samy Moussa. With direction and choreography by Wayne McGregor, the work features tenor Sean Panikkar as Oedipus and mezzo soprano Dame Sarah Connolly as his doomed mother, as well as dancers from the Dutch National Ballet. Fascinerend!

Still in The Netherlands: the Dutch National Opera Academy recently finished a run of Conrad Susa’s spicy chamber opera Transformations. The 1973 work features texts by Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Anne Sexton and subverts the archetype of the fairytale in a very unique, sometimes even disturbing (hurrah!) ways. The two-act work is a very adult re-telling of ten famous Grimm stories, including Rapunzel, Rumpelstiltskin, and Snow White. Susa’s work was widely performed in the US following its premiere, but only had its continental European premiere in 2006 in Lausanne and was later presented at the 2006 Wexford Festival Opera. I do wish this work was done more, especially since fairytales seems to play such a large if unconscious role within modern aesthetics and design.

… and Rusalka

Indeed, the timeliness of presentations that contrast long-cherished fairytale-related art is noteworthy, what with their unmissable corollary to contemporary digital imagery and its over-Photoshopped Insta-friendly narratives. But hostility to such cliché-breaking is abundant, and that hostility been underlined in the opera world with angry reactions to the new production of Rusalka at the Staatsoper Unter den Linden in Berlin. Dvořák 1901 work, which shares various elements with The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen, is here stripped of its familiar long-haired-doe-eyed-fair-slim-water-maiden imagery. Director Kornél Mundruczó, together with designer Monika Pormale, presents something far more provocative –though to my mind, it shouldn’t be provocative at all. Such presentations are sorely needed, especially within the current cultural landscape.

Mundruczó isn’t the first to dare to strip the opera of its traditional aesthetic. Sergio Morabito, who staged the opera with Jossi Wieler in 2008, described Rusalka to Jessica Duchen in 2012 as a “really dark fairy tale. It’s really desperate – without any hope.” Part of this bleakness is linked to the main character’s muteness, though that narrative device has been presented in a variety of ways through the years. From a personal standpoint, robbing a girl of her voice for the sake of some idea of humanity connected to “romance” (and soft-focus tragedy) is nightmarish – dress it up any way you want; it’s still horrific. Reading comments about the Berlin production lately I was reminded of past Rusalkas, especially unconventional ones like those by Morabito/Wieler as well as the grimy (if great) 2012 Stefan Hernheim production; both kicked against the soft-focus aesthetic but in so doing attracted incredible vitriol. That a Rusalka might go against some set-in-stone image is bad enough (Kosky’s infamous Carmen arguably did the same), but that it should dare to present a title character who, likewise, doesn’t conform to a deeply conservative image of “the mythical (or mysterious) feminine” is unforgivable.

Is there value in upsetting the traditional aesthetic connected to certain operas? To paraphrase a recent conversation with a friend on just this topic: even if you don’t agree with every little choice in a production (especially the presentation of the main character), you can at least recognize the work’s place more broadly within the sphere of modern presentation. For reference: I have reservations about various aspects of the updated productions of both Strauss’s Daphne at Staatsoper Unter den Linden and Johann Strauss’s Die Fledermaus at Bayerische Staatsoper, but I wholly support them being done. It’s important to try these things! As Morabito also noted in his interview with Duchen in 2012: “We don’t like the idea that we are making abstract aesthetic statements and people must swallow it or die! We think and hope that people wouldn’t have preconceived expectations.”

Classical writer Gianmarco Segato recently saw the very first presentation of Rusalka by the Hungarian State Opera and staged by director János Szikora. In his review for La Scena Musicale Segato cleverly notes the extent to which its designs were influenced by early 20th century Czech artist Alphonse Mucha and Art Nouveau more broadly, especially with relation to the opera’s titular character and her cohorts. In Berlin, reactions to Mundruczó’s far less imagistically romantic production have been divisive. Albrecht Selge covered the opening for Van Magazine (auf Deutsch) recently, describing soprano Christiane Karg in the titular role and arguably capturing its whole essence: “Denn Karg gestaltet ihre Nixe agil, zornig, aufbegehrend gegen die vorgegebene Opferrolle.” (“Karg makes her mermaid agile, angry and rebellious against the predetermined role of victim.”) It’s important to try these things – especially, I would argue in the age of Instagram!

Professor Pfefferkorn auf Insta

Speaking of the ubiquitous, ever-evolving, image-obsessed platform: music publisher Breitkopf and Hartel has an entertaining, intelligent weekly Insta-series that dives into the nitty-gritty of their work and broader realities for the industry. The format is simple, along with the aesthetic: head honcho Nick Pfefferkorn addresses viewer questions in quick if informative talks from his desk. (Special thanks to whoever thought to include the English subtitles.) Pfefferkorn, who founded his own independent publishing house in 1996, became publishing director of the Wiesbaden-based Breitkopf and Hartel in 2015. His narration style is equal parts tweedy professor and watchful butcher; he’s detailed in discussing the finer points of just how the music-score-sausage is made at this particular publisher.

These videos are helpful in demystifying what can be an intimidating part of deeper music engagement. I feel a bit less daunted at re-examining the various ingredients of scores in my own collection through watching Pfefferkorn’s detailed if direct explanations. Last week’s episode focuses on how the publisher indicates page turns, for which section, and why some indications differ from others; he starts with something more fashion-oriented. Vielen dank, B&H!

On Emigré

Deutsche Grammophon recently announced the upcoming release of Emigré, a 90-minute new oratorio by Emmy Award-winning composer Aaron Zigman, with lyrics by Mark Campbell and songwriter Brock Walsh. The work details a little-known piece of 20th century history, when the people of Shanghai welcomed Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Europe in the 1930s. Emigré examines this history through the lense of a story about two brothers and their respective journeys. Premiered in Shanghai last November, the work will receive its North American premiere in a semi-staged production at Lincoln Center at the end of this month, and is scheduled to be presented by the Deutsches-Sinfonie Orchester in Berlin at an as-yet-unannounced future date.

Emigré was co-commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and the Shanghai Symphony, as well as its Music Director and conductor Long Yu, who was called “the real hero” of the project in a recent panel discussion hosted by classical NPR station WQXR. The upcoming New York staging will feature tenors Matthew White and Arnold Livingston Geis in the lead roles, together with sopranos Meigui Zhang and Diana White, mezzo-soprano Huiling Zhu, and bass-baritone Shenyang, a former BBC Cardiff Singer of the World.

The project comes at a time when the classical world is realizing that it’s good to express a greater cultural awareness; my cynical (read: observant) self says this is also good marketing and optics for an industry that still has such a long way to go. But it is equally true that classical organizations and labels are being silently expected to step in and offer the history lessons that many educational systems sorely lack. So if Emigré aids in raising awareness and opening conversations, so much the better. It is disheartening to note the lack of Canadian dates for performances of Emigré, but hopefully that will change.

Finally, who says Beethoven and belly-dancing can’t be combined? Here’s “Für Elise” like you’ve probably never heard it:

Like music journalist Axel Brüggemann says, “halten Sie die Ohren steif” and remember: the c-word is context. 😀