|

| Vladimir Spivakov and Hibla Gerzmava with the Moscow Virtuosi at Roy Thomson Hall. Photo: Vladimir Kevorkov for Show One Productions |

Is this the year of great singers making their Canadian debuts? Perhaps.

Soprano Anna Netrebko and husband, tenor Yusif Eyvazov, appeared in Toronto this past April (along with baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky), as part of a concert co-presented by the Canadian Opera Company and Show One Productions. This past Thursday, (8 June) soprano Hibla Gerzmava made her debut in the city, joined by conductor Vladimir Spivakov and the Moscow Virtuosi Chamber Orchestra, who has led the ensemble since formation it in 1979.

Gerzmava, who hails from Abkhazia (located on the eastern coast of the Black Sea), is a singer of some acclaim. I’ve been following Gerzmava’s work for a number of years, particularly her annual gala concerts (called “Hibla Gerzmava Invites”) that feature a who’s-who of great classical-world talent. She’s a singer with a laser-pointed tone and a warm, textured sound. I had the chance to see her live last fall in Don Giovanni (not shocking to those of aware of my fascination with that work) at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, with famous baritone Simon Keenlyside in the lead; Gerzmava’s Donna Anna was pleading, angst-filled, guilt-wracked. Her performance of “Non Mi Dir” was lovely, with Gerzmava shaping her rolled consonants and luxurious vowels into a rapturous embrace.

|

| Paul Appleby as Don Ottavio, Hibla Gerzmava as Donna Anna, and Simon Keenlyside in Mozart’s Don Giovanni. Photo: Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera |

Aside from that memorable voice, what makes Gerzmava interesting to me is that the same year she graduated from the Moscow Conservatory, in 1994, she became the first singer — and the sole woman ever — to earn the prestigious Grand Prize in the prestigious International Tchaikovsky Competition. Since then, she’s appeared on some very notable opera stages, including the Wiener Staatsoper (Vienna), the Bayerische Staatsoper (Munich), Bavarian State Opera, Opéra National de Paris, the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, the Met of course, and the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, among many others. This past spring she sang the title role in Donizetti’s dramatic opera Anna Bolena (part of his Tudor trilogy) at Teatro Alla Scala Milan (opposite venerable Italian bass Carlo Columbara as Enrico / Henry), one of the most challenging of roles within the repertoire, both musically and dramatically.

|

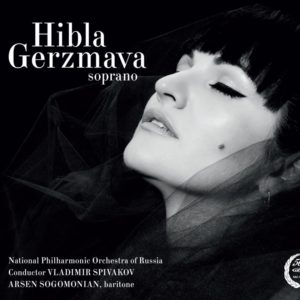

| (via Melodiya) |

Gerzmava’s recent albums, Hibla Gerzmava, Soprano (Melodiya), released in 2014) and Opera. Jazz. Blues. (Melodiya), from 2016, explore an array of sounds, with the latter focusing on jazzy forays into traditionally classical repertoire (with arrangements by Daniel Kramer), and the former an impressive live recording of a concert she gave in Moscow with Spivakov and the National Philharmonic Orchestra of Russia in 2013. She gives thrilling readings of many opera classics on this album, every piece full of laser clear tone and dramatic verve; it’s a highly listenable album, and I think it works really well as an introduction to opera overall, offering a nice selection of well-known favorites, wonderful interpretations (including a lively rendering, together with baritone Arsen Sogomonian, of the duet between the main female character and the charlatan-doctor character in Donizetti’s L’elisir d’Amore, or The Elixir of Love, another huge favorite of mine), and the sparky dynamism of live performance. Consider that a recommendation for those of you who are a bit nervous about sticking your toe into the opera ocean; trust me, this is a nice bubbly jacuzzi best enjoyed with a good cold glass of rose.

Currently on tour with the Moscow Virtuosi Chamber Orchestra through North America, Gerzmava made her Canadian debut Thursday night at Toronto’s Roy Thomson Hall (the regular home of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra), offering a highly eclectic program featuring works by mainly French and Italian composers. After a first half that featured Spivakov leading the Ensemble in an a wide array of works (including Mozart, Shostakovich, Bruch), as well as a sparky performance by young cellist Danielle Akta, Gerzmava appeared, splendid in a grand, floor-sweeping red/blue/gold dress, with long hair neatly pinned up, and launched straight into one of the best-known arias within the operatic repertoire (also featured on her live album), “Casta Diva”, from Bellini’s Norma. It could well be suspected that Gerzmava was facing a few challenges (she appeared to be sucking on some kind of lozenge or candy at several points), what with some uneven moments vocally, and a gradually diminishing volume throughout the concert that left her with a small but very sweet tone for the evening’s encores, the famous “O Mio Babbino Caro” (from Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi) and Strauss’ ethereal “Morgen“, also featured on her live album. Whatever vocal color she may have been lacking, Gerzmava made up for with brilliant flashes of the muscular tone for which she’s rightly celebrated, particularly in the middle portion of the program. Her renderings of the showpiece stretto aria from Verdi’s I Masnadieri (The Robbers) and “Ecco… Io son l’umile ancella” (“I am the humble servant) from Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur were standouts for their tonal clarity, light if well-considered vibrato, and the fierce dramatic heft of their delivery.

|

| Vladimir Spivakov and Hibla Gerzmava with the Moscow Virtuosi at Roy Thomson Hall. Photo: Vladimir Kevorkov for Show One Productions. |

Gerzmava showed herself so deeply cocooned within the music she was performing at points as to be acting out the parts to and with various orchestra members, who gamely played to her, along with conductor Spivakov; it would have all come off unbearably corny but for the fact that Gerzmava, and her fellow musicians, were so very clearly committed to the music, and to the moments of both intimacy and grandeur within the music. Some pieces were more like duets, which made Gerzmava’s and the Virtuosi’s connection with the music that much more touching. Here’s to many more appearances by Gerzmava in Canada in the future, and fingers crossed for not only some Russian repertoire in that program, but some Mozart, too.