Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Owing to the realities of the coronavirus, the days of crowded orchestra pits may be some ways off to being fully realized, but restrictions have created large opportunities for the small. Reorchestrations are not new, of course; history is filled with examples of composers reorchestrating their own work and that of others. Mahler, Mozart, Stravinsky, Strauss, and Schoenberg all reworked (or, in fashionable parlance, “reimagined”) their own compositions and the works of other composers, contemporary and not, as need (social, financial; sometimes both) dictated and creative curiosity allowed. Such reworkings reshape one’s listening, in small and large ways, and shake up the foundations of perception (conscious and not) which come to be associated with particular sound worlds.

Conductor/director Eberhard Kloke’s reorchestration of Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier at Bayerische Staatsoper, a new production helmed by Barrie Kosky and led by Music Director Designate Vladimir Jurowski, was one such pandemic-era production providing this shake-up. The opera, and its composer, are deeply intertwined with Munich and its cultural history, with many opera-goers holding specific memories of related work by conductor Carlos Kleiber and director Otto Schenk. Appreciating a new version of something old means prying off the determined octopus which has wrapped itself around the object of musical worship; usually the tentacles spell out things like “comfort”, “nostalgia”, even “expectation” and “ego.” Analyzing the whys and wherefores of one’s listening habits, as such, is not always pleasant, but is necessary. Along with being the incoming Music Director at Bayerische Staatsoper (2021-2022), Jurowski is Chief Conductor and Artistic Director of the Rundfunk Sinfonieorchester Berlin (RSB). As I observed in 2018, the Russian maestro is well-read and very articulate; just as he spoke at length about Mussorgsky, programming, and stagings back then, so he now speaks about the act of reorchestration and its historical and creative antecedents – what works, why, and how; to quote the Marschallin, “in dem “Wie” da liegt der ganze Untershied” (“the how makes all the difference.”).

Thus has curiosity and anticipation for the new staging grown since the opera’s livestream presentation on March 21st. Despite having studied Kloke’s reduction of Strauss’s score (published at Scott Music), the experience of hearing it was, and remains, deeply poignant, even rendered through home speakers; if reduction and translation are analogous, then so too must be the act of reading to one’s self versus the full sensory experience of hearing the words aloud in all their syllabic, rhythmical glory. Frissons of shock and sincere wonder raced through veins in experiencing the online presentation, with Strauss’s grand cotillion on dewy grass becoming a deliciously barefoot belly-dance across an ornately-patterned rug. Taste is personal, but so are hang-ups; the awareness is all. The “how” indeed makes all the difference.

Our conversation took place in early 2021 in relation to a magazine feature I was writing at the time (for Opera Canada) about opera reductions in the age of pandemic; that feature also had insights from tenor John Daszak and Canadian Opera Company Music Director Johannes Debus. For the interests of education, possible inspiration, and clarity into the wide world of reorchestration, I was granted permission to publish this exchange with Maestro Jurowski, in full. Make a pot of tea, sip, and enjoy.

You’ve done a few reductions, haven’t you?

Officially I did one which was aired on Deutschlandfunk Kultur (radio) – I did it during the first lockdown (spring 2020). It was a longtime dream of mine to do a version of a piece which I’ve loved for years and which for some strange reason never become really popular, although other works by the same composer have made it into all possible charts – I’m speaking of Prokofiev here, and the piece which I have created of is The Ugly Duckling, the fairytale after Hans Christian Andersen. It’s a piece Prokofiev rewrote several times himself; he wrote the first version of it in 1914 for voice and piano, and then he came back a few years later and did a version still for voice and piano but a different voice, a higher voice, so he started by amending the vocal lines and ended up amending the whole structure. He moved the keys, not all but some, so it became singable for a soprano; I think it had to do with the fact that his first wife, Lina Prokofieva, was a soprano, and he reworked it for her. Then he came back again much later, about 20 years after the piece was finished (in 1932) and created an orchestral version. I always found it fascinating composers creating orchestral versions of their own piano pieces. In the case of Prokofiev there are two famous examples, one is The Ugly Duckling, and the other one is his Fourth Piano Sonata (1917); the slow movement of this sonata, the Andante, he later made into a self-standing piece of orchestral music, the Andante Op. 29 (1943), and that is a firework of compositional craft, comparable with the best orchestrations of Ravel, who was orchestrating music by other people too, like Mussorgsky’s Pictures At An Exhibition; in the same vein, Rachmaninoff did a very interesting arrangement of his Vocalise, originally written for voice and piano, which he later reworked into an orchestral piece, first with solo soprano, and then a version where all first violins of the Philadelphia Orchestra would play the tune and a small orchestra would accompany.

So Prokofiev wrote The Ugly Duckling having a certain type of voice in mind, and then he came back and orchestrated it, but in such a way that made it literally impossible for a light voice to perform, simply because the orchestration was too heavy; I wanted to bring the piece back to where it belonged, in the realm of chamber music. So I chose to do a version of it for 15 players, which is the normal size of a contemporary music ensemble; it all springs from Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony #1, which was scored for 15 players. I realized very soon that it was impossible to simply reduce the missing instruments; for that size of group you have to re-balance the score, and very often I found myself in need to address the original piano score. So, I was moving along the confines of Prokofiev’s orchestral score, but eventually what I wrote was much closer to the original piano score, and that made me realize again how huge is the gap between what composers set for piano, two-hand piano, and the same music being reimagined for large orchestra – it becomes a different piece. It’s a different weight, there’s a different sound world, there are different colors in it, and obviously it produces different kinds of emotions in us listeners. If you take a Beethoven string quartet and simply double each voice, so play it with 40 people rather than with four, it won’t automatically be 40 times stronger – it will be louder, for sure, but not necessarily as balanced, because it’s like alchemy; you multiply the numbers, but different numbers in the same mathematical relationship calls for completely different sound effects.

What kind of effects?

For instance, one violin, obviously, is a solo instrument; if you have two violins playing the same tune, acoustically, it would create a clash. Even if they were playing ideally in tune, you would still hear two violins. Take three violins, and make them play the same tune again, and it will sound much more unified. At four, it will sound again heterogenic. Five is better than four, and three is better than two. At six you would still hear a small ensemble, and somewhere between seven and eight you will start hearing a section. When hearing a section playing a single note or a melodic line, it gives this melodic line or this note a completely different weight, and not necessarily a bigger weight, than when played by one person.

“Weight” is a good word within the context of what is lost or gained. How do you approach weight in orchestration when you are reducing a score?

You have to shift it; it’s like in tai chi, shifting the weight of your body from the centre to the left foot and then the right foot again, and so on. So you’ve got to decide exactly how many instruments you leave on the melodic voice and how many instruments you would leave with the harmony, how many instruments you’ll give to the bass… it’s not always mathematically, I mean, obviously you could calculate everything, but not all of these calculations will be obvious. So for me the scores of Richard Strauss or Rimsky-Korsakov, to give you two very different examples, or late Wagner, are such examples of perfect calculation. When it comes to others, well, some don’t understand how to go about composing for the weight of a symphony or orchestra; they might treat the orchestra like a large piano, and that is, with permission, wrong. An orchestra is a different instrument – Bruckner treats the orchestra like a huge organ, and that’s sometimes very strange, it seems much less plausible than treating the orchestra like a piano, but it calls, interestingly, for better results.

But composers who write specifically for the stage, for singers: that is a whole different beast.

It is! And that is where the problems start. So Strauss was among the first composers who not only sanctioned reduction of his scores, because Wagner did too, Wagner sanctioned the reduction of several of his operas, most famously Tristan, but Strauss was among the very first composers who started doing the job of reduction himself. And that is where you can see the difference between an artisan, a very secure craftsman being at at work, and a real artist being at work, because Strauss’s own reductions of Salome and Elektra, and the few fragments from Die Frau Ohne Schatten which he reduced, they are masterpieces, and near-ideal examples, entirely didactic examples, of how one should go about reorchestration. Another example of such reorchestration in the sense of adding weight is Mahler. When Mahler revised his symphonies, especially such symphonies as #4 and #5, the amount of weight loss these scores have undergone in Mahler’s hands is mind-blowing – yet they never lost their essence.

So I think, essentially, it’s like this: the composer always knows best. They always know how his or her works should sound with different, let’s say, smaller, forces. But what you need to do as an arranger is to get into the mind of the composer and crack the DNA code of the piece. You basically need to put yourself in the state of composing the piece within you – not with your own mind, but the mind of the composer. Once you’ve done that, you’re able to do any type of technical operations with a piece without damaging its essence, because one thing is simply reducing a score, and another thing is reducing a score in such a way that it would still sound its very recognizable self in this new attire, in these new clothes. For instance, Schoenberg’s own reorchestration of Gurrelieder was originally scored for a huge orchestra, and he created his own reduction for a chamber orchestra; I think it is an ideal example of how a composer reinvents the same piece with much more discreet means and yet it appears to you in all its glory. And yet I’ve done, during the pandemic, several reduced versions of symphonic pieces of opera. While in Moscow (in November 2020) I did a concert with a reduced orchestration of Götterdämmerung. I didn’t do the complete piece but selected fragments and that was a well-recognized, you could say, classical reduction by Alfons Abbas (1854-1924), published by Schott, and obviously going back to the composer himself, and yet I have to say, having done it, I… never felt at ease with it, because I always felt the piece was being betrayed.

Why?

Because by the time Wagner came to composing Götterdämmerung, he really knew why he used such a huge monstrous orchestra. In the first pieces, in Rheingold or Walküre or even in parts of Siegfried you would argue, he was going for more sound, for more volume – by doubling, by adding up stuff – but by the time he came to composing Götterdämmerung and even more so in Parsifal, he had a perfect command of those full-voiced chords, distributed among the four voice groups, meaning each wind group had four players, and when you started redistributing them, between the groups – because obviously a normal orchestra would have only maximally three players per section – then you get into all sorts of trouble, and then I thought, it would have actually been better, more honest, and certainly more productive, reducing it further, from quadruple not to triple but to double, so you exactly half the size of the players – just as Kloke did in his reduction of Wozzeck – because (in) leaving three original instruments and adding one on top, there’s always this torturous moment of choosing the right instrument: what do you add to three flutes, an oboe? Do you add a clarinet? Do you add a muted trumpet? Whatever you add won’t sound right.

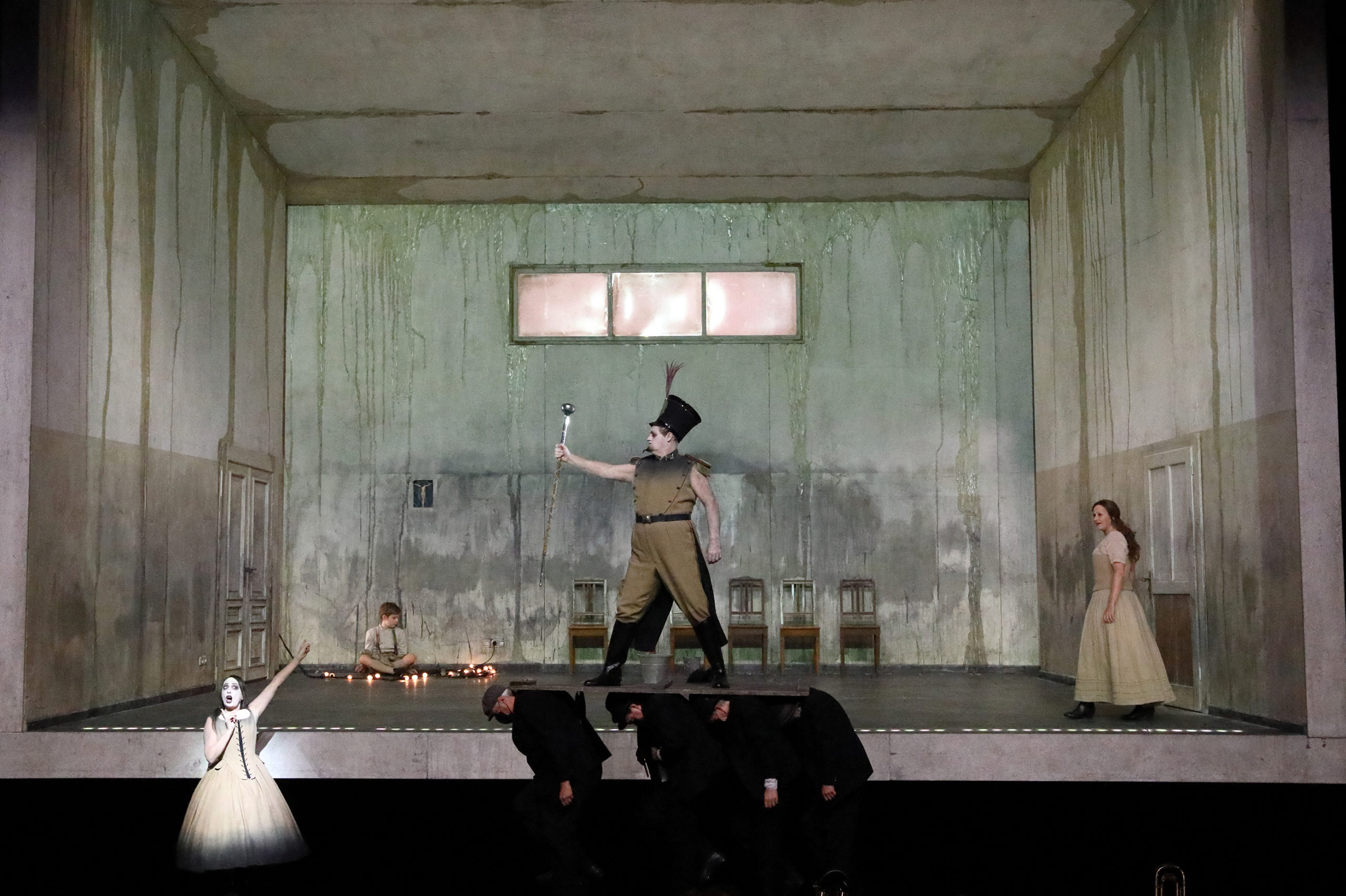

Wozzeck at Bayerische Staatsoper, 2020 (L-R): Ursula Hesse von den Steinen (Margret), John Daszak (Tambourmajor), Anja Kampe (Marie). Photo © Wilfried Hösl

And so, I’m coming to the conclusion that orchestration and reorchestration is a very special art which resembles the art of poetry translation. We know poetry is untranslatable, and that there are very rare cases where you find a translation which is completely idiomatic; most of the time you just get the very dry account of the events of the poem’s plot, or you get one very neat rhyme, if the original poem was rhymed – which makes a new composition, which might be a very interesting work in its own right but has little to do with the original poem. It is the same with the art of reorchestration. It depends also on what your aim is as the orchestrator; is your aim really to give the piece a new birth in these new circumstances but still keep its essence? Or are you after some very bizarre effect of deconstruction? One needs to be careful when dealing with these orchestrations, and reorchestrations, in that one can, in trying to translate the composer’s thoughts, become a traitor of the composer.

How so?

Well Stravinsky used to say to the performers that any kind of interpretation is mostly an act of betrayal toward the original’s composition. That’s why Stravinsky demanded strict following of the original text and no personality of the performer. At the same time Stravinsky himself, when re-orchestrating his own works, redid them every time, but in such a way that they became new pieces. Look at the three versions of The Firebird, the 1910, 1919, and 1945 versions: there are three different versions, there are three different birds. It’s not the same bird in a new dress; it’s a different bird – a bird which sings the same song, but the song gets a completely different meaning. The same happened with Petrouchka (1911), the same happened with Symphonies of Wind Instruments (1920); when they got revisited in later years – Stravinsky often did it for financial reasons because he wanted to renew his copyright and get maximum revenue from performance of the pieces – he couldn’t help updating them to the new stage of compositional career he was at, at the time.

How does this relate to current trend of reduction then?

Well, I’m of two minds on this whole issue of reorchestration, because on the one side I find it fascinating business and a fascinating time, because it gives us so many opportunities to revisit the pieces we all know, but… I find a slight problem in that mostly works are not being revisited by the composers themselves, but by people who are our contemporaries. We’re talking of composers who are long dead, so unless they are artists of an equal level… well, who could be on an equal level with Wagner, Strauss, or Mozart? It’s worth remembering, when you think that Luciano Berio created his version of Combattimento di Clorinda by Monteverdi in the 1960s – when Hans Werner Henze created his version of Ulysses (1985); when Strauss created his version of Idomeneo (1931); when Mozart created his version of the Messiah (1789) – those were genius composers dealing with works of their genius predecessors. Speaking of more recent events, Brett Dean reorchestrated Till Eulenspiegel by Strauss for nine performers (1996); even if I disagree with some decisions (in the reorchestration), I’m always finding such attempts much more plausible and worthy of being performed than some (recent) reductions which were done for practical reasons by people whose names become slightly more familiar to you now, because they’ve touched on the great, famous compositions.

By Tucker Collection – New York Public Library Archives, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16243459

Where does Kloke’s approach to Rosenkavalier fit into all this, then?

Kloke has created something unique, first as a conductor, then as a programmer, and eventually as a reinventor of these old great pieces. His role is comparable with the role of a modern opera director who is revisiting the old pieces and sometimes deconstructing them, but there is always a thought, there is always a good reason. You might disagree with his solutions and ideas, but they are always done with an artistic purpose; that isn’t always the case. And, now is the heyday of rearrangers, because we are all forced to either completely take leave of certain compositions for the time being, or to hear them in reduced formations. I personally have no problem in waiting for another four or five years until a performance of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony becomes possible in its original Gestalt, to do it the way Mahler conceived it with a large orchestra, than in doing it now in one of these multiple available reduced forms. I’ve looked at all of them and the only symphony which I have done in reduced orchestration and I found absolutely plausible was #4, because it is in itself a piece of chamber music; there were moments where it was missing a big orchestra but they were a few.

And, I haven’t done it yet, but I would like to do Schoenberg’s orchestration of Das Lied (Von Der Erde), simply because Schoenberg knew Mahler, so it is the pupil revisiting the work of the great teacher – but no other symphonies. Likewise I would have absolutely no interest in performing a reduced version of The Rite Of Spring.

So this time has changed the way you program?

Yes… yes. My whole philosophy during the time of the pandemic was to keep as much as possible the names of the composers in that co-relationship in which they were programmed. For instance if I had, let’s just imagine the names of Mozart and Strauss on the program, then I would try and keep Mozart and Strauss, but a work by Mozart can be kept anyway without any amendments, you just reduce the amount of strings and you can still play it, but in the case of Richard Strauss, if the piece was the Alpine Symphony or Zarathustra, I would never even *begin* to think of performing a reduced Zarathustra or Alpine Symphony; I think it’s a complete waste of time.

Does that attitude, of keeping certain things in their original Gestalt, extend to opera as well?

Yes. For me The Ring is such a piece, as a tetralogy. There are certain pieces like Rheingold – I know there is a version by Jonathan Dove which the Deutsche Oper presented in the carpark last year, that he reworked all four for Birmingham Opera originally – but for me, having done this little bit of Götterdämmerung with my Russian orchestra (in late 2020), I felt I had to keep it because it was just an important symbol of hope to give to people: “You see we are still performing, we can still do it.” But artistically I remain deeply unsatisfied with the whole experience; it had nothing to do with the orchestra or the wonderful singer (soprano Svetlana Sozdateleva) who learned Brünnhilde for us, it was just not the sound of Wagner as I knew it and as I would expect it; all the beauty of Wagner’s wonder machine, this symphonic orchestra he invented, was gone. It was simply a very crafty piece of orchestration, but nothing else. There was no magic in it at all.

At the same time, I found when we had to go back to smaller sizes – the string orchestra in performances of let’s say early Beethoven symphonies or something like Symphony Classique by Prokofiev – the pieces gained from it, hugely, so there was a loss but there was also a gain, and the gain was in clarity and virtuosity, in transparency and all that. The question is, do you want more transparency in pieces like… Tristan?

I was just going to mention that precise opera…

I mean, is that what you want? For transparency?

.. yes, in direct relation to transparency. You took the words out of my mouth there.

Right?? So, yes – I would choose my pieces very carefully these days. Specifically in relation to what I’m preparing now, Der Rosenkavalier has this neo-classical aspect which got later developed by Strauss and Hofmannsthal and found its most perfect resolution in Ariadne auf Naxos, especially the second version with the prologue, composed in 1916. Revisiting Rosenkavalier from the backward-looking perspective of Ariadne I find very interesting. I am not saying that this is an absolute revelation and this is how I want to hear my Rosenkavalier from now on – I would be lying! I want to go back to Rosenkavalier as we knew it before! – but I bet you there will be discoveries through this smaller version which will help us when working on the piece again in the larger orchestration, to work on the finesse and bring out the theatricality of the libretto.

Actually the main difference between the small version and the big version is, the big version, however transparent you do it, you still first hear the orchestra and then the voices; with the smaller version you can almost perform it as a play, with background music. And I am sure Hofmannsthal would have been thrilled because he thought of the piece as mainly his composition, with music by Strauss; we tend to think of it as a great opera by Strauss with text by Hofmannsthal. So there are two ways of looking at it.

But Wagner… ?

Well, when it comes to something like Parsifal or Tristan or Götterdämmerung, I think the pieces are perfect the way they were conceived, so I personally, with all due respect to the people who reworked these operas now for smaller forces and those people who perform them… I personally don’t think it’s the right thing to do; I would keep my fingers away from it. As I would keep my fingers away from Shostakovich Symphonies, apart from #14 which was composed for chamber orchestra, and I would wait as long as is necessary until performing them again. I would not touch on any Prokofiev symphonies or big Stravinsky ballets or Mahler, Bruckner, symphonies, what you will; I simply think there is a limit beyond which the reduction changes the pieces beyond the level of recognizability – and then I much prefer to sit in my armchair and look at the score and imagine how the piece would sound, or listen to a good old recording. I mean, it’s everybody’s right to decide what’s best for them, and there is no right and wrong here. Besides it’s always better to have some music in whatever form than no music at all, but my feeling is also there’s been so much music composed over the last 2000 years, well, even take the last 500 years or so, you could fill hundreds of lifetimes with programs, never repeating the same pieces; why do we always have to come back to the same pieces over and over again?

Because they’re crowd pleasers, they sell tickets, they put bums in seats…

Yes, and because they give us this sense of safety, because we come back to something familiar, we can cling on to that, etc etc, again, anybody has the right to do what they think is best for them, but I had absolutely no hesitation in cancelling all these big pieces and replacing them with other pieces by the same composers or in the case of Mahler, there is actually nothing which can replace Mahler 9, nothing at all, so I would say, if we can’t play Mahler 9 now, we play a different piece by a different composer, we just leave it at that; there are some things which are irreplaceable.

Director Barrie Kosky (L) and conductor Vladimir Jurowski (R) rehearsing Der Rosenkavalier in Munich, 2021. Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Perhaps this era will inspire audiences not to perceive reductions as a poor compromise but as a new way of appreciating an old favorite.

Yes, and you know, I’m always asking myself – again, this is me being a grandson of a composer – I’m always asking, “What would good old Richard Strauss have said to all this?” Because knowing Strauss and his ways from the many letters and diaries he left, and the bon mots he pronounced in conversations with other people, I think he would have still preferred hearing his work in a strongly reduced version, than not hearing it at all. So I think when it comes to Strauss, he of all people would have been actually rather happy hearing his Rosenkavalier even if what we are going to present in Munich will be very, very far removed from the sound world of the Rosenkavalier he thought of when he composed it. In his time as President of the Reichsmusikkammer, the Ministry of Music in Nazi Germany – a position he held until he fell out with Goebbels – Strauss insisted on ruling out the possibility of performances of some operas by Wagner by smaller theatres because he thought performing these works with orchestras less than such-and-such-number of strings were an offense to the composer, so he was quite… in that time he was quite radical with his views. Because people then were much less purist than they are now, they just wanted to hear their Lohengrin, and they’d gladly hear it with six first violins. Just as recently, in Munich before everything closed down completely (in late 2020), (Bayerische Staatsorchester) was playing in front of 50 people, when (just prior) they were playing in front of 500 – they were playing Tosca with six first violins, and Swan Lake with six first violins, and you know, that was the only possibility. That’s why, when I came to Wozzeck, I thought, “This is a good one; this piece was sort of the cradle of modernism, and we will find a good version of the piece, reinvented” – and we did find that version, in Kloke. There is an even more drastically-reduced version for 21 musicians…

Yes! I was prepared to play it as well! I said, “If the restrictions will go that far, then we’ll play this version for 21 musicians.” It was almost an act of defiance back then, but now, when these things become normality, when we see that the next few months, maybe the next six months, maybe the next year, will be all reductions, I think one needs to choose carefully.

For instance, I completely reprogrammed the season in Berlin; I remember when we published the program of the RSB in, it was right at the beginning of the lockdown March-April last year, there were some journalists in Berlin who said, we were lunatics, we were completely out of touch with reality that we were presenting this program which was completely impossible, and I said then, “I’d rather present something which is impossible but which represents my dream, a certain way of thinking about the music, and then I will bring it in cohesion with reality.” I’d rather do that, than simply leaving all the dreams behind, and presenting some completely randomly-made program simply because we know, “Oh there is a pandemic coming and we can’t play this and that.” I’d rather say, “This is what we thought of; this is what I would have ideally liked to have played. And now we see we can’t, we still try and weave our program along the pre-made lines of this concept.” So we had all the Stravinsky Russian ballets and many other works, and of course none of them will happen now, it’s clear, but I would still have a Stravinsky festival in Berlin, and we will already start, we have already had a few pieces by Stravinsky and we will keep that line, the same will apply to Schnittke or Denisov or almost any composer, the only ones we left out completely without replacing them were the really big ones such as Mahler 9 or Shostakovich 8, there is no replacement for them.

But I’m quite hopefully because you know if you see how composers themselves developed – take Stravinsky for instance, he started composing for these monstrous-sized orchestras and eventually lost interest in them, later in his life the more chamber musical or unusual he got the combinations of instruments got more and more unusual and the compositions didn’t lose any of their qualities, they simply became something else. So if we take composers’ development as our guide, then we certainly won’t get completely off-road.

Marlis Petersen as the Marschallin in Barrie Kosky’s staging of Der Rosenkavalier at Bayerische Staatsoper. Photo © Wilfried Hösl

But how much will stagings match that whilst complement the overall spirit of the current era?

Well our Rosenkavalier will also be different to the one originally envisioned by Barrie Kosky; it will be a corona-conforming production. And I’m sure when we come back to revisiting it in the post-corona times, obviously, as every new production will be revived hopefully multiple times, we’ll change it once more. But again, I’m thinking of Mahler, who would change the orchestration of his symphonies every time he would conduct them in a different hall with a different orchestra – it was never the same process. It was Mahler who said, “Hail the conductor who will have the courage to change my pieces further after my death.”

… which, in my mind, underlines the flexibility of audiences’ listening then; it’s interesting how auditory intransigence – ie, “x opera has to sound exactly like this, the end” – doesn’t match composers’ visions…

… because for the composers their pieces were part of a living process, a *live* process of genesis, it was part of their life and they were still alive and as they were alive they were changing things along the way…

… but that’s music.

That is music! Mozart would compose extra arias for his operas and take some arias out in the next edition and he would also have very different orchestra sizes depending on the places where he would perform them. Our problem is that we have this… this is a completely different subject matter and it would take a whole separate conversation… but, we got fixated. It’s like an obsession with the music of the famous dead composers. So that we found ourselves in this museum where everywhere there is in a line saying “Don’t touch this; don’t come close!”

It’s not a separate conversation though, it’s part of the reason some organizations have closed instead of trying to find ways to perform. They assume audiences will be afraid of that different sound.

I agree with you, absolutely. But it’s a different thing when we are scared of reductions: we might injure the essence of the composer’s work or we might simply injure our little feelings provoked by certain compositions, so basically we’re not interested most of the time – we’re not interested in the music; we’re interested in the emotions this music provokes in us, and we want to have a push-button repetition of the same emotions over and over again.

“I want to feel THIS during Aida; THAT during Rosenkavalier… ”

Precisely.

… but I think this is an opportunity for examining those preconceptions, and asking asking what our vision of “normal” even means now.

What does “the normal” mean in the post corona times, yes – because anything will feel completely abnormal, everything will feel huge and new and very exciting, and playing Beethoven’s 9th again or Mahler 5 will feel like a real revelation. People will get heart attacks, hopefully positive heart attacks, from being in touch with this music again – certainly us musicians will.

Some of us audience members are also musicians.

So you can get a heart attack, then – hopefully in a good way.