Certain sounds inspire one to sit up a little straighter, look away from the monitor, pull up the blinds, gaze out the window, and then remove the pandemic uniform of fleece loungewear and replace it with something more elegant and beautiful. Thus it is that those sounds – singers, operas, concerts, arias, and oratorios – have worked in tandem to provide a much-needed uplift over the course of the past fifteen months, aiding in a more focused, thoughtful, and elevated quality of energy than much of the classical internet, and its overdue if very often over/underwhelming digital pivot, tends to demand at any given moment in the age of Covid. Lisette Oropesa’s debut album, Ombra Compagna: Mozart Concert Arias, released via Pentatone earlier this month, provides such uplift, along with a hefty dollop of inspiration.

Recorded in August 2020 with conductor Antonello Manacorda and orchestra Il Pomo d’Oro, the album’s ten tracks showcase Oropesa’s poetic musical sense, as well as her talent for balancing the whirlwind spirals of drama with the straight-arrow trajectories of technique. Hearing such luscious sounds, one immediately adjusts one’s spine, fixes one’s hair, puts on a nice dress; it feels as if the artists, and composer too, would request nothing less, or more, in the era in which the album was recorded and released. Three tracks feature the words of Italian poet and librettist Pietro Metastasio (1698-1782): “Misera, dove son!”, (composed in 1781) “Alcandro, lo confesso – Non so d’onde viene” (1778) and the album’s closer, “Ah se in ciel, benigne stelle” (started 1778; completed 1788). The latter two arias were composed for Aloysia Weber (1760-1839), an accomplished singer whom the composer had taught and been enamoured with prior to his marrying her sister, Constanze (in 1782); the works are notable for the poignant musical ideas which fully anticipate more fulsome creative expression in Le nozze di Figaro (1786) and La clemenza di Tito (1791) . Oropesa’s handling of the aural and textual aspects of the respective arias expresses a touching emotional honesty; the knowing way in which the soprano delicately modulates her tone and breath, her studied phrasing and vivid coloration, imply a comprehension of things beneath, around, between, and beyond the words. “Alcandro, lo confesso”, for instance, is from Metastasio’s libretto for L’olimpiade (Olympiad), and was originally set to music by Antonio Caldara, who was court composer to Empress Elizabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (the work was originally meant to celebrate her birthday). As John A. Rice’s fine album notes remind us, “(t)he concert aria gave composers and performers flexibility in regard to the gender of the singer vis-a-vis the gender of the character portrayed. To be more specific: a female singer could freely portray a male character.” Such fluidity is conveyed with quiet elegance through Oropesa’s controlled if unquestionably heartfelt delivery, complemented by Manacorda’s stately tempo and dynamics:

Alcandro, lo confesso,

stupisca di me stesso. II volto, il ciglio,

la voce di costui nel cor mi desta

un palpito improvviso,

che lo risente in ogni fibra il sangue.

Fra tutti i miei pensieri

la cagion ne ricerco, e non la trovo.

Che sarà, giusti Dei, questo ch’io provo?Non so d’onde viene

quel tenero affetto,

quel moto che ignoto

mi nasce nel petto,

quel gel, che le vene

scorrendo mi va.Nel seno a destarmi

sì fieri contrasti

non parmi che basti

la sola pietà.Alcandro, I confess it,

astonished by myself. His face, his

expression, his voice—they awaken

a sudden tremble in my heart

which the blood repulses through my veins.

I try to find the reason in all my thoughts,

but I can’t find it.

Good Gods, what is it that I feel?I don’t know where this tender

feeling comes from,

this unknown emotion

that is born in my breast,

this chill that runs

through my veins.Pity alone

is not sufficient to cause

those strongly opposed feelings

in my breast.(English translation by Christina Gembaczka & Kate Rockett)

With a rich vocality displayed in the frequently challenging, wide-ranging works, Oropesa’s flexibility and confidence, together with her calculated blend of sass, class, and deep sensitivity, show an artist flowering in a range of colors and styles. The concert arias demand, as Oropesa writes in the album notes, “extremes of range, breath control, dynamics, and stamina” and the soprano’s versatile technique (well explored through her history with Italian repertoire, especially bel canto) is keenly studied, if easily received.

That’s the point, Lisette said when we chatted recently – the music should sound effortless, even if it’s anything but – in content, as much as in style. Having such multi-faceted awareness is, for the singer, central to understanding and expressing the depths of real, lived emotional experience within the music; even if the topics are mythological, the subtext is far more familiar.The album’s title (which translates as “companion spirit”), originates in the aria “Ah, lo previdi” (“Ah, I foresaw it”), used in a scene from Vittorio Amadeo Cigna-Santi’s libretto for Andromeda (1755); it uses the recitative form for maximal dramatic impact whilst offering a careful musical scoring that highlights aural power to convey the speaker’s grief over what she believes is her beloved’s passing. As Oropesa writes, “the most sublime music accompanies the journey between life and death, as the spirit of a loved one slips away.Though we may wish to follow them into the next life, we must stay behind. So to be an “Ombra compagna,” to be with someone in spirit”, when we say that, it is a comforting yet heartbreaking testament of love.”

https://open.spotify.com/album/3zGXZPYFNCDsSYsrFFSVn2?si=Vh0Q-mkAQr-BHktd6pJ5lg

Known for her work on the stages of Bayerische Staatsoper, Wiener Staatsoper, Teatro Alla Scala, Opéra national de Paris, and the Met, Oropesa is acclaimed for her performances of Italian, French, and German repertoire; she is especially known for her performances as Verdi’s Violetta (La traviata) and Donizetti’s Lucia (Lucia di Lammermoor). Zooming recently from Arizona, Oropesa was warm, funny, real, moving with ease and humour between discussing music approaches and dishing life lessons, with the same warmth and honesty as I remembered in our previous chat in 2019. Despite the challenges of the past year-plus, Oropesa’s upcoming schedule is busy, and, along with recordings and performances in Paris, Zurich, and Vienna, features concerts in California, Italy, and, in March 2022, a much-anticipated concert appearance at Teatro Real Madrid. January 2022 sees the soprano perform the title role in Bellini’s I Capuleti e I Montecchi, after being unable to perform at the season opener for the fabled house in December 2020 because of coronavirus-forced closure.

We began by discussing Ombra Compagna and how the project came to fruition amidst the numerous restrictions necessitated by the pandemic.

How did you choose material – why Mozart?

I didn’t actually pick that material! I am a big Mozart fan and I sing a couple of the concert arias; I studied them, but Pomo d’Oro wanted to record this material and they wanted me to sing it –they were the ones who reached out originally. I didn’t have a label at the time, so while I said yes to them and “it sounds great, send me a list of which arias you mean, there are so many and some are out of my realm of possibility but some are doable, I’d have to study them” – shortly thereafter Pentatone reached out. We had a meeting, and they said, “We want to offer you a package deal for six albums: three recital discs and three opera discs, and I said, would you consider this Mozart project? They said, “Yes, that would be a great first disc!” – so that’s how it happened. From there, Pomo d’Oro sent me a list of arias they were originally thinking of me doing. I chose which ones I wanted, and went on a journey; I got all this sheet music and spent a long time studying and listening to stuff, trying to find what arias were more well-known, ones that had and hadn’t been done. I did pick the arias but didn’t plan the project. In our business so much is given to you, and you either take it or you don’t; very few artists are capable of manifesting their own dreams into any reality. I had wanted a record deal for years, so I’m happy. To produce an album is akin to buying a house: to get an orchestra together, hire a conductor, order scores, find the space for recording, get in the right sound engineers… it’s a lot. So this was great, because someone else produced it. Pentatone is a label that very much cares about sound quality and specifics, and their producers have a lot of experience with orchestra and voices.

And artistically, if you offer me a Mozart project, I’ll never say no! In recording this, I had to find ways I could sing and interpret these works, because they’re all written for different individuals and that means, in a lot of ways, they’re tailored to specific voices: some might have amazing jumps, some might have great coloratura, some might have dramatic capabilities. Every aria has its own personal stamp, so I had to find my way of interpreting all of that, with the best of what I can do. I’m not a master of every single technical thing but I can do a lot of things okay enough that, I can probably pull from my experience – I can pull my flute experience here, I can pull my band experience there, I have my experience with recitative – and the fact I feel comfortable in Italian was very helpful too. The conductor (Antonello Manacorda) was a concertmaster and leads a lot of Mozart so we got on really well, and the orchestra are a great Baroque ensemble. They tuned down to 432Hz for some things; because I am not the highest-sitting a soprano right now, that made my life easy. It was fun, the whole thing. I loved it!

You really personalized the material in your approach.

You have to – really, you have to! I was telling someone the other day, with a lot of people singing Mozart, it’s like watching a gymnastics routine or an ice skating routine; we’re waiting for the jumps and flips and landings. And that’s fine, but those routines in particular, even though they’re sports, they’re also artistic: you’re looking for elegance and beauty and seamlessness of one move to the next, and the power of the gymnast who has their own way they move. In that respect, it’s like singing Mozart: you can’t just look at the technical demands and not go past that into what he is really about, which is depth of emotion. And you can’t do the emotion without the technical stuff – that’s a doorway into the realm of what I think Mozart really is, but you can’t start from that side of the door, you have to go through the technical door first. The problem is a lot of people – artists, industry people, listeners even – get very hung up on the door, but we have to get past it. It’s a tough thing to do, so I try to make the easiest-sounding door possible. Whatever technical demands there are, I try to make them sound easy, even though they’re not. But if I make it seem hard you won’t get past it.

Then all we’d hear is a door.

That’s right!

With Artur Rucinski in Lucia di Lammermoor at Teatro Real, 2018. Photo; Javier del Real

Your bel canto experience must have been good preparation too…

Tremendous. Bel canto helps you with learning to use recitative in a way that is emotionally effective. Mozart is a beautiful writer of recitative so I never had an issue. These arias are all accompagnati; the orchestra is playing, it’s not with just a harpsichord, which you get in his operas – so because these are concert pieces, the entire orchestra is involved, even doing recit, and you might be doing it for four pages before the aria starts. It’s odd to sing it in a way, but it’s also a dramatic part of the piece: you’re setting up the story and that’s very nice as a singer! The other thing is that being a former instrumentalist is really helpful; I learned to express music that didn’t have words, I learned how to express a musical intention, a phrase, without text. With text, sometimes it’s all singers obsess over, this “What about this consonant? What about this vowel? How should I put across all the immense poetry?” – and yes, all of that is important, but with Mozart, the text and the musical phrase are joined; the musical phrase is as vital as the text. Ideally, you marry those two things together when you perform.

Would you say they’re lieder-esque in a sense… ?

Yes, they are.

I hear a lot of Schubert and Beethoven being anticipated in these works, and especially in how you perform them, which made me consider how much I’d like to hear you doing these works in recital.

Thank you, that means a lot. I love lieder, especially the Viennese school and the German stuff; it’s some of the best rep in the world. One of the good things about the pandemic, one of the few silver linings, is that solo-singer-with-piano configurement has become much more popular; I have a massive book full of recital rep that I’m preparing for next year. It’s months’ worth of recitals – the bookers all want lieder, so honestly? Yay! I’m ready, I’m bringing it!

That echoes what Helmut Deutsch said to me earlier this year, that he feels the time has come for lieder. But of course, lots of people are still recording too.

Well yes, recording was the only thing people could do for so long, because orchestras were free and you could record, as long as you were distanced and the room was aired out, and you tested throughout the process. It was one of the only things still allowed to happen. I did three albums myself since this whole thing has happened, and realistically, I’d never be able to book them otherwise; most singers are never free, they need a week at least of just recording, and normally no one can spare the time, so (setting time aside to record) is a scheduling issue (in relation to opera houses). But this past year everybody’s been recording or rehearsing, or learning new roles.

What’s that like for you as a singer, to be taken away from audience energy but to get closer to your voice and to other musicians?

It is a chance to navel-gaze at our larynx, haha! And, not having the audience when you’re doing an album is not a problem because you’re focusing on just recording; you can rehearse, worry about the singing, you don’t have to please a director, you don’t have to wear a costume, you can wear the flat shoes, no makeup and do your thing. I never recorded with an orchestra before – this was my first taste of doing that, and even though we were distanced (so it was slightly less intimate than it would normally be), I was maskless and I could sing into the mic, start, then stop; repeat.

Now, doing performances like an opera or a concert, without an audience… that sucks. We can do it, but. What happens in rehearsal is, you’re basically rehearsing and then you run the whole show with an audience of your castmates, which is intimate and beautiful, but the next level is presenting it to the public; that is what you are preparing to do. And then to do that presentation with no public present, except on the internet – we can’t hear them, or see them – it almost feels like you’re still rehearsing somehow, like you painted something but didn’t hang it on the wall. There’s no finished feeling, and that’s odd; there is no energy back, and that’s odd. So you can sing your balls off and then you don’t hear any applause or reaction – you can’t feel what the audience’s energy is toward you – and that’s awful.

I read a piece about the LSO recently which underlined the point about the need for an audience. ”Why else are we doing this?”

That’s right, why else indeed?

But lately I feel I have to wave my arms about this; yes, you do it to fulfill an innate creative urge, but related to that, at least to my mind, is the desire for energetic feedback.

Exactly right. I mean the thing is, we, and this is what’s been hard, the public comes to us for escape in some ways. We are entertainment for many people; they come to the theatre to dream, and that’s been taken away from them, but, we as artists are expected to still perform at the same level, or a more high level, because everything is so hard now, so it’s “Please come perform on the internet for an audience you can’t see or hear!” You’re doing it for less money and for much more stress and much more risk, and the stakes are 100 times higher; as artists we’re stressed beyond belief doing this, and we still have to put that aside, and put emotions to the side. It’s hard enough when things are functioning normally – there’s enough difficulty in the business as it is – but now there’s far more; there’s world stress, there’s financial stress, there’s various forms of personal stress, and there’s still this attitude, like, “Sing for us! Entertain us! Sing under these circumstances!”

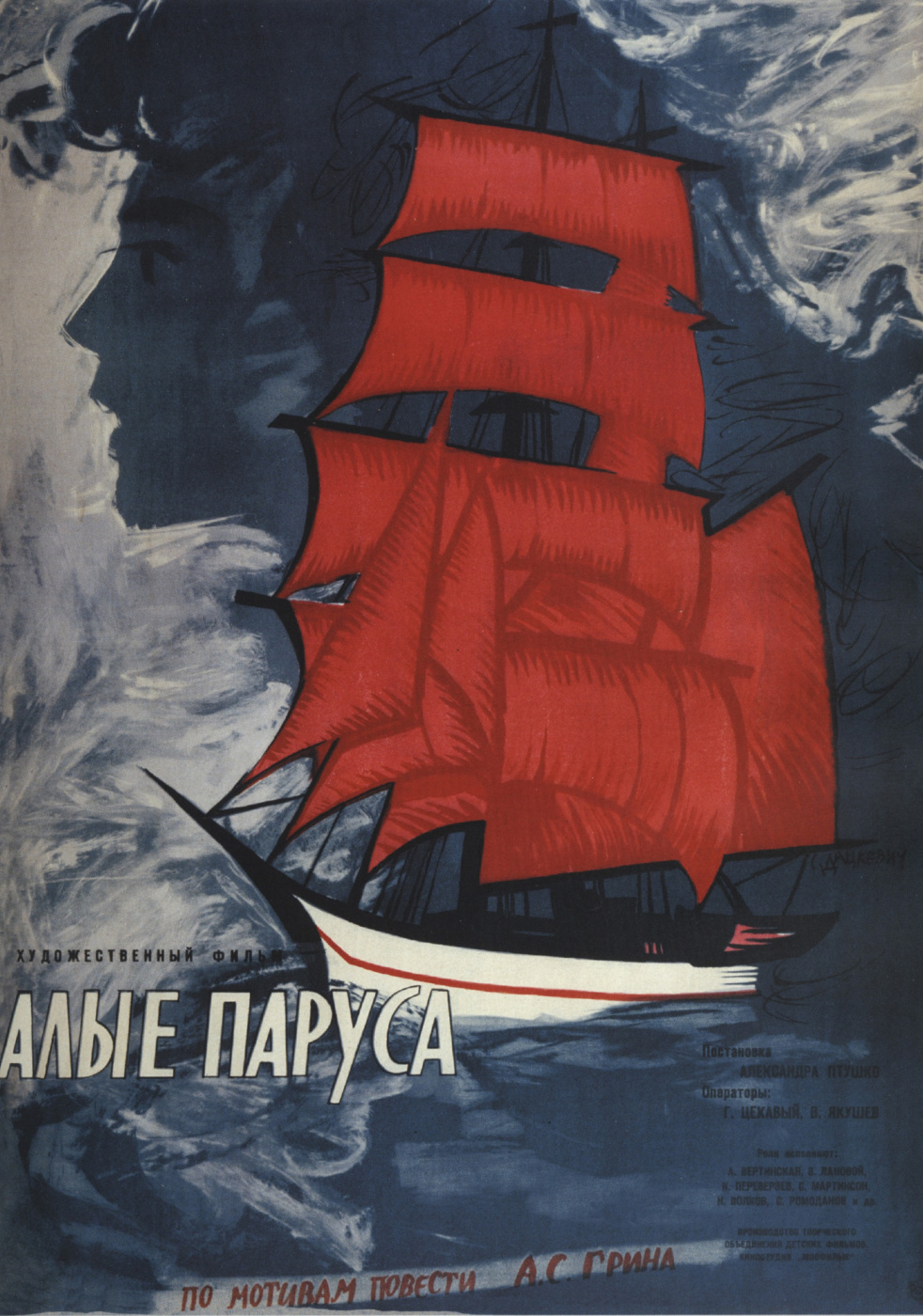

In La traviata at Teatro Real, 2020. Photo: Javier del Real

Your work as a singer is being filtered through the choices of a director as well; it must create a weird self-consciousness not only about how you sound, but how you look.

I’ve talked about this with regards to opera in HD – you don’t get to direct what frame is on the screen at any given moment, so you might be on camera or not, doing all this great work, but no one will see it if the director doesn’t choose you. And then there will be these snap judgements – “He’s a bad actor!” – but in theatre you can pick where you want to look. The energy and electricity of performers reaches audiences in a different way live than through a camera. Cinematic awareness is something we are having to deal with more and more, yes – I made a movie in Rome of Traviata, and we did so many takes of every scene, live-sung, with the orchestra piped into a speaker. We had to follow as best we could, and I had no idea which take they ultimately took. My mother saw rough cut and said, “That director likes your back!” and a friend in film said, “Oh that’s a specific directorial thing, seeing what (Violetta) is seeing rather than presenting an outside perspective” but I was doing all these things with my face, because I have experience in theatre, and theatre is much more immediate.

It’s surprising how many don’t understand or appreciate that immediacy, implying the big digital pivot is somehow going to “save” opera and how it needs re-defining; I wonder if the real issue is better cultural education.

It is, because the art form does not need redefining – I 100% agree with you. Opera does not need redefining; it does not need watering down, it does not need censorship. It is actually more progressive than people have interpreted it as being, even though it isn’t always presented that way, but it can and should be presented in different and new ways. Opera also provides one of the very best opportunities for women to work: as a prima donna, as a lead character, as a very central if not entirely pivotal character on the stage. I mean, I’m lucky I don’t have to compete with men for my job.

The pandemic era has shown that a lot of companies definitely needed to up their digital game, but lately it feels like music is the last thing to be considered.

You’re right; it doesn’t seem like the music is that important sometimes. I feel at the moment that the focus is more on, “how many people can we reach”, “what are the numbers”, “what social message can we put out”. Some companies are trying to do innovative things, like performing in a parking garage, a racetrack, an airport… but I think, look, we’re not cars. We don’t belong in cement buildings. I know we’re trying to do the distance thing and I get the whys and wherefores of that, but an opera voice is meant to resonate in a concert hall that’s designed in a very specific way to showcase this very specific thing. It’s the same thinking as, ‘let’s put a ballerina on a cliff and make her dance’ and sure, she could, but her shoes aren’t made for that, her training isn’t made for that, it’s taking this very particular craft and sticking it in another medium it isn’t made for, and as a result it doesn’t come across the same way.

And it isn’t perceived the same way as a result; there’s pluses and minuses to that. But to me the central issue is still one of education, or lack thereof.

Yes, and so I’m hoping (the activities of the past year) are just a patch job and not a permanent thing. I know San Francisco Opera just built a whole outdoor theatre, a whole new one. I mean, their War Memorial War Opera House still exists…

… they might be trying to do what’s been done in other places in terms of adding to the outdoor summer festival scene. But the question of what role the music plays in all this still niggles.

Yes, I mean, where does the music go when these sorts of construction things happen? You lose a lot of the intimacy in those giant settings…

… sure, but it’s not a new thing; Arena di Verona exists, and other spectacles have come and gone. I remember attending Aida at the local stadium as a kid, and that was really not about the music. The sound was horrendous but it looked impressive.

Some things don’t work outdoors, and some do. The problem is that (outside stages) force singers to adopt a whole different way of interpreting the music, and Aida has a lot of intimate moments. How would you expect a soprano to sing “O patria mia” in a stadium? That’s a very internal moment, that aria, she isn’t barking it – and sure, The Triumphal March works great, it’s 800 people and the orchestral scoring is very exciting right then – but for much of the opera, it’s just two people or one person singing on the stage. It’s a story about relationships, and you can so easily lose sight of that. It’s the same for any of these operas about individuals going through intimate experiences – in Aida or Traviata or Rigoletto. Actually, Rigoletto was staged at Circus Maximus – the stadium where the chariot race in Ben Hur was filmed – last summer; now, Rigoletto is about a father and a daughter, and a very complicated, close relationship, and … you know, in such a big space… I don’t know, it’s unusual. But somewhere like Arena di Verona, it’s an amphitheatre, it’s good acoustics, the stagings are done at night; there’s a special sort of vibe there.

Singing for the internet is a whole different thing, I’d imagine…

Oh yes – for broadcasts shown in a cinema or for the internet, you have to deal with a crappy little microphone hidden in your bosom or wig, and then try not to think about the fact that you’re singing for somebody’s crappy computer speakers. And: the majority are judging your voice. You are totally aware that the online audience are often critical and anonymous. Everybody’s a critic and has a platform to bitch and moan about not sounding good, but look, it’s not fair to watch and judge a singer’s voice on this platform; overtones don’t get picked up, color largely do not translate, subtle things you do with your voice do not translate, and there are these weird resonances. Now, a real hall has acoustics which are designed to promote those things in a proper way; at La Scala a voice bounces, as it should, and you can’t get that in speakers. I don’t know how else to explain it. When you train as a singer in school and take lessons you are not training to sing into a microphone; you are trained to sing over an orchestra and/or another instrument, playing loudly, in a hall. That is our training. If you tell me to take my training and do something else and expect me to be brilliant and get everything perfectly, there’s a problem.

And, we are not trained to act for a camera; we are trained for the theatre, our faces are meant to be open and expressive, and we are taught a certain level of exaggeration in ways that underline enunciation and presentation. You stick that on camera and it looks unflattering, over-exaggerated, not believable, silly. Then you get told, “Well tone it down for the camera” and you think, I’m supposed to be singing for 3000 people here, but apparently I should… be subtle? It becomes this whole issue, and then it goes into, “This person doesn’t look good on camera because they are old.” And they’re not old at all, they’re at a perfect age, they’re good-looking, and, yes, they sound amazing! But it’s become this new “normal” for singers, that they look “old” somehow.

Ombra Compagna was released via Pentatone in May 2021.

Right, we’ve discussed this Instagram issue and how tough that is for women especially – so again, the music gets left behind, because follower numbers are more important, being sexy is more important, how it will all magically translate into ticket sales…

… exactly, “People love her, she has lots of followers, she looks hot in a bikini…”

“… and we have to attract a younger, hip audience, so…”

… “we have to attract a younger audience” is dog whistle for, “We have to get the heavy, unattractive, older people off.” Why are we trying to attract them? In Europe there are tons of young people going to classical events; if you make it cheap enough, the younger patrons will attend, and, if you don’t try to water it down into these headlines, like, “Passion! Jealousy! Opera!” That sounds like a telenovela, come on, they see through that. But the marketing to young people involves us singers now, too, so any singer with a decent following – organizations tend to use us to advertise, and that’s fine, they can do it; that’s the reality.

So much marketing adds insult to injury by implying knowledge is somehow bad, that it’s elite to educate your potential audiences.

If people think they don’t like classical music, or that it’s elite, then ask them to turn on any movie/series/TV show, and tell me what it is they’re hearing and responding to. I’ll tell you: it’s classical instrumentation and writing. 90% of the time people are responding emotionally to a theme while something is happening. Classical is an art that deals in human emotion; it happens naturally. You can play a video game and the music is gorgeous, epic, classical music, most of the time, it’s otherworldly – so if people don’t think they’ll like it, well, they might. It shocks me sometimes, the ignorance, but classical is absolutely mainstream. And so I don’t think it’s any more elite than the Olympics. People think classical is so hoyty-toytoy – but it’s like going to a nice restaurant or a special dinner; you have certain protocols you follow. That should be something you look forward to doing, like going on a date. Do you really want to go in your PJs?

Ah, but that’s the uniform this year!

Right? Lounge-office wear is the fashion in 2021 now!

I actually took off the lounge-wear and put on a dress to listen to your album; I still do.

Oh thank you!

It felt elevating and inclusive at once, and that is an integration Mozart seems especially good at.

Mozart is not a composer who leaves people out – he’s one of the more easy-to-listen-to composers. It’s why so many of his works are known by so many people, in and out of the realm of classical music. It’s melodic, harmonic, theatrical, entertaining, not too much chromaticism, nothing people wouldn’t get, but so human. His work is a great introduction to classical music overall.

Various singers have told me they love returning to the music of Mozart because his music is a massage for the voice – is that true for you too?

It is, yes, and it can be a really great thing to get you in line vocally. If you are everywhere with your voice, Mozart is a very challenging composer. He demands you understand the door, to go back to our image from earlier; all the hinges have to be lined up, everything has to be right, and just so. Only then, yes – walk through that door; Mozart wants you to.