Photo: Frank Blaser

There’s a certain logic to particular careers beginning in particular ways, especially ones that anticipate future pathways.

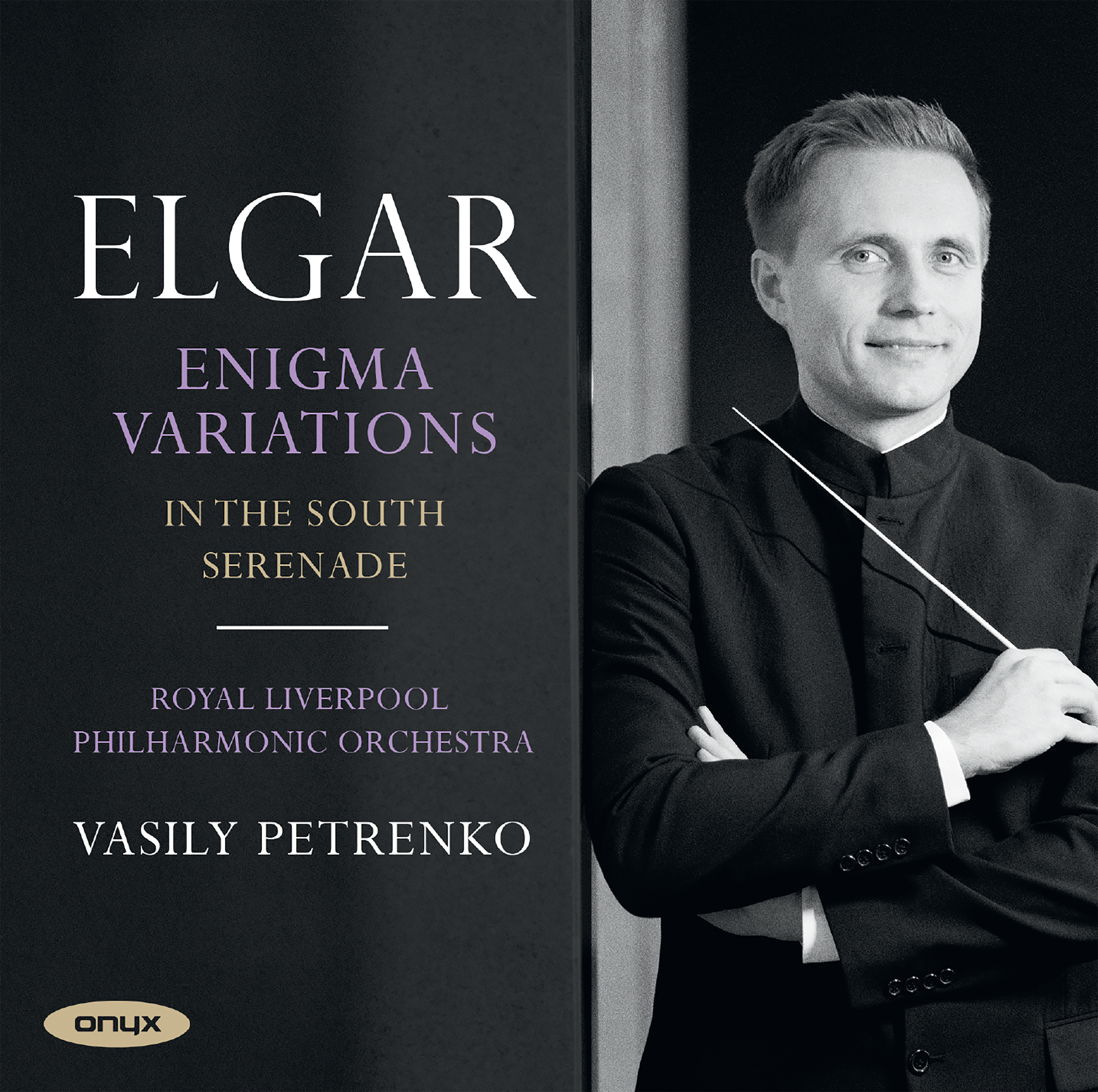

Oper Zürich Intendant and director Andreas Homoki is known for his strong creative vision, so it’s fitting that his own opera career didn’t begin in an quiet way, but with a work featuring big ideas and sounds, with Strauss’ monumental Die Frau ohne Schatten in Geneva in 1992; it went on to win the French Critics’ Prize upon its transfer to Paris’s Théâtre du Châtelet in 1994. As a freelancer, the German-Hungarian director went on to stage a myriad of works (by Gluck, Verdi, Mozart, Humperdinck, Puccini, Lortzing, Bizet, Strauss, Berg, and Aribert Reimann) for houses across Europe (Cologna, Hamburg, Hanover, Leipzig, Munich, Berlin, Basel, Lyon, and Amsterdam), before becoming Principal Director of the Komische Oper Berlin (KOB) in 2002; he ascended to General Director (Intendant) in 2004. Over the next eight years, Homoki, who hails from a family of musicians, helmed productions of Eugene Onegin, La bohème, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Der Rosenkavalier, The Cunning Little Vixen, The Bartered Bride, and The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, as well as giving the world premieres of two works on the KOB stage: the children’s opera Robin Hood by composer and singer Frank Schwemmer, and Hamlet by composer-conductor-pianist Christian Jost.

Homoki went on to became Intendant at Opernhaus Zürich in 2012, replacing Alexander Pereira (currently the outgoing sovrintendente of Teatro alla Scala), who had been in the role for over two decades, and who’d been responsible for bringing some much-needed pizzazz to the Swiss opera scene. Pereira also famously insisted on a myriad of new productions each every season. The company grew considerably under his leadership in terms of the ambitiousness of its stagings as well as its clout within the broader international opera scene. But as I wrote in my feature on Zürich’s classical scene for Opera Canada magazine last year, “if Pereira brought a cosmopolitan energy, Andreas Homoki brings a highly eclectic one.” Such eclecticism is frequently expressed in his choice of repertoire. Homoki has made a very conscious decision for the company to heartily embrace its past, fortifying ties with the city’s artistic roots and reminding audiences of the contemporary (and in many cases, theatrical) nature of the art form. Oper Zürich is where, after all, several important twentieth century works enjoyed their world premieres, among them Berg’s Lulu (1937), Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler (1938), and Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron (1957). Der Kirschgarten, by Swiss composer Rudolf Kelterborn (based on Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard) was presented in 1984 to inaugurate the newly-renovated house.

Opernhaus Zürich. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission)

Since his arrival in 2012, Homoki has staged numerous productions (Lady Macbeth of Mtensk, Fidelio, Médée, Wozzeck, I puritani, and Juliette by Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů), and helmed the premiere of Lunea by the celebrated Heinz Holliger, about the life and work of 19th century polymath poet Nikolaus Lenau. (One reviewer noted the production was “one of the season’s most unforgettable, if pointedly cerebral, musical encounters. Indeed, Lunea may well set the stage for the next generation of opera.”) In May 2020, Oper Zürich presents another world premiere, Girl With The Pearl Earring by composer Stefan Wirth, which will feature baritone Thomas Hampson as painter Jan Vermeer. In addition to creative programming, Homoki has introduced pre-performance chats as well as “Opera for all” live broadcasts at Sechseläutenplatz (the largest town square in the city), an initiative he began at the start of his tenure. Homoki doesn’t so much court risk as embrace expansion. “In the arts, everything less than the maximum is ultimately insufficient,” he noted last year, adding:

We as artists are increasingly caught in a balancing act between the demands of parts of the audience always wanting to see what they cherish and parts of the specialist press and opera world calling for new interpretations. We are sometimes pulverised by the conflicting expectations. My aim is to overwhelm the audience so much with the overall experience of opera that it actually forgets it’s even at the opera. This is admittedly a maximum aspiration but nonetheless achievable.

Such aspiration has manifest not only in terms of his repertoire choices, but within the approach he takes to stagings. Homoki’s wonderfully absurdist production of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk (conducted by Teodor Currentzis) was a million miles away from the bleakness that so often characterize the work’s presentation, offering a vividly surreal vision while simultaneously offering poignant insights about the fraught nature of human relating. Strong reaction doesn’t seem to bother him; Homoki’s unconventional if highly fascinating take on Verdi’s La forza del destino last spring was met with criticism, to which he said that booing “is often part and parcel of an innovative production. Particularly for productions that collide with traditional views. You have to live with it.” By contrast, Homoki’s commedia dell’arte-meets-puppet-theatre vision of Wozzeck (first staged in 2015) was met with high praise, one review observing “a finely honed production that follows its premise to an absurdist conclusion with slick theatricality and dispassionate zeal.” It will enjoy a revival at the house in February 2020.

This force of his vision extends far beyond his own projects. “I don’t hire directors who are not able to surprise me,” he commented in 2018. Zürich audiences were certainly treated to surprise or two last autumn, with highly unconventional productions by Barrie Kosky and Kirill Serebrennikov. Kosky, the current Intendant of KOB, brought a highly unique and psychologically unsettling staging of Franz Schreker’s Die Gezeichneten to the stage. Together with conductor Vladimir Jurowski, the production offered a decidedly different vision to the ones previously presented in Munich and Berlin; whole scenes, characters, and large swaths of the score were entirely excised, with the results sharply divided audiences and critics alike. Serebrennikov, the recently-freed Artistic Director of the Gogol Centre in Moscow, presented Cosi fan tutte (led by conductor Cornelius Meister) not as a romantic comedy but as a dark drama, with the male leads having been killed in battle when the production opens. Homoki hired Serebrennikov after seeing the Russian director’s staging of Salome for Oper Stuttgart in 2015 and his The Barber of Seville for KOB a year later. Last fall, Homoki strongly stood by the Russian director as he tried to helm Cosi in Zürich while still under house arrest in Moscow, telling a Swiss media outlet, “I could not let down this man I consider innocent.“

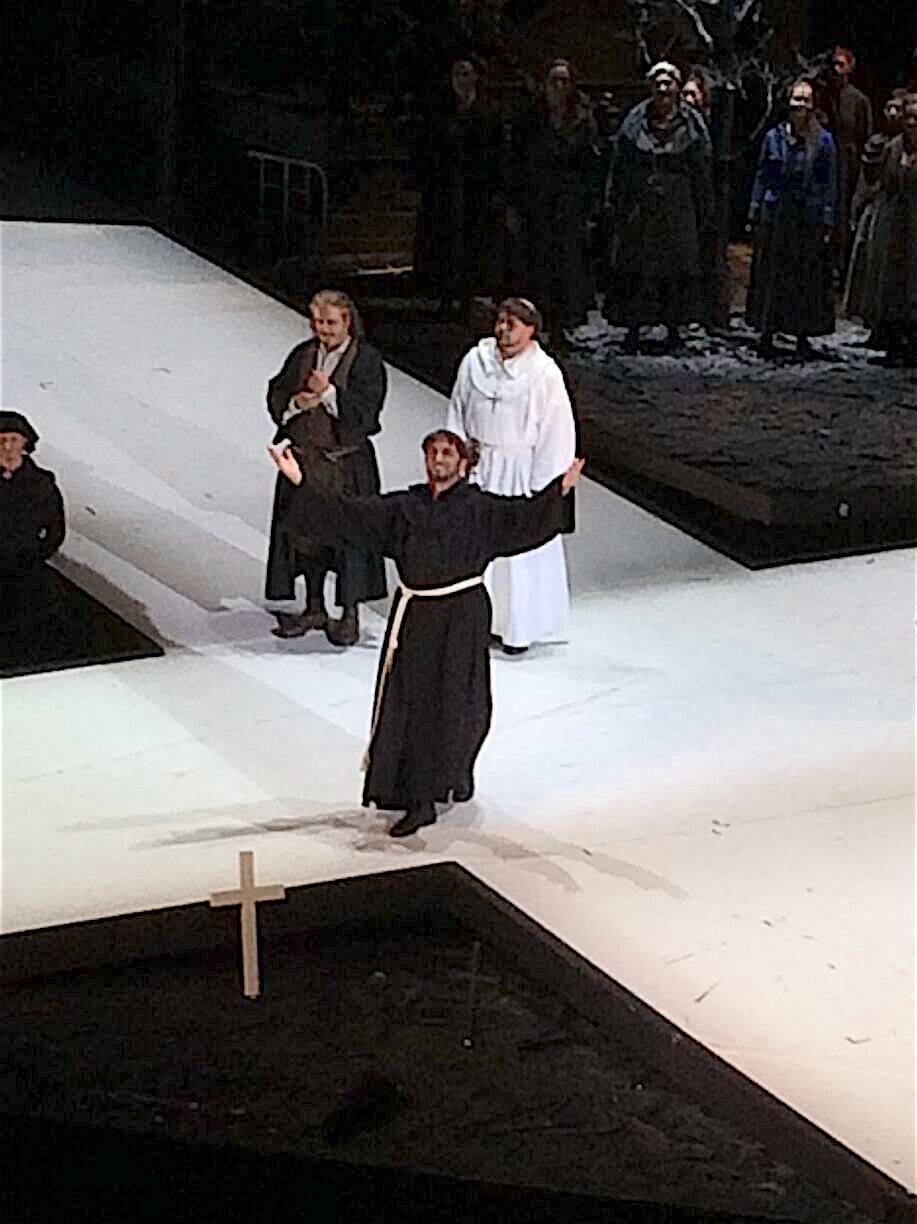

Last month Homoki and his efforts were recognized when Zürich won Best Opera House at the inaugural Oper Awards in Berlin, with the eight-member jury commenting that “(t)he director’s intuition for new, innovative directors, the commitment of the best of the established and the consistently top-class cast of singers with exciting debuts make the Zürich Opera House under Andreas Homoki a most worthy address.” The Intendant himself commented that the award was “an incentive to live up to one’s own expectations” in future. It remains to be seen if he’ll live up to those expectations this season, which promises to be a busy one, but the director seems determined to give his all. His older productions of Hänsel und Gretel, Rigoletto, and La traviata are to be staged this season at Deutsche Oper Berlin, Staatsoper Hamburg, and Oper Leipzig, respectively, and his new production of Gluck’s Iphigenia en Tauride will be presented in Zürich in early February. The house will also host a raft of his revived productions, including Nabucco, Fidelio, and Lohengrin, and Wozzeck. In addition, Homoki returns to the Komische Oper Berlin, where he’s set to direct Jaromír Weinberger’s 1926 romantic comedy Schwanda der Dudelsackpfeifer (Schwanda The Bagpiper) – a so-called “ode to Bohemia” – which opens in March.

A quick note for clarity: owing to flight mishaps, Homoki and I weren’t able to actually speak on the telephone but Homoki did kindly offer thoughts via email.

A question for many leaders in the opera world has been balancing new work with old favourites. How much of a challenge have you faced in presenting contemporary works at Opernhaus Zürich?

The Zürich Opera has the great advantage of being able to produce nine new productions on the main stage per season — and entirely on its own. This allows us to offer a broad programme, which includes all periods from early Baroque to the contemporary. We therefore present at least one contemporary opera, if not a commissioned world premiere, plus usually one piece of the twentieth century. We are actually obliged by the government to commission at least one new opera for our main stage every second year, which we are happy to do!

However, we have to be aware that contemporary operas do not attract the same audience figures as major repertoire titles. We therefore program contemporary titles a little more carefully with less performances and special marketing.

At the inaugural Oper Awards in Berlin, September 2019. (Photo: © Kathrin Heller)

How closely do you work with conductors? Does it differ between individuals? I find the dynamic fascinating because so much of the energy of that relationship is felt onstage. What’s your approach?

It is during the rehearsal process when the collaboration between conductor and director gets important as it affects the detailed work with the singers who have to merge both musical and dramatic aspects to shape their stage character. It’s therefore important to verify beforehand that both tend to a similar point of view with regards to the staging. This also refers to possible changes in the musical shape, such as cuts or special versions of certain operas. However, the conceptual work of the director is much more time-consuming. Another important partner for a director at the very beginning of his considerations are his designers, since the stage design is part of the overall production concept, which is created at least one year before the start of rehearsals.

I work with Dmitri Tcherniakov (Oper Zürich: Jenůfa, 2012; Pelléas et Mélisande, 2016; The Makropulos Affair, 2019) because I like good directors who are not only able to develop their own strong vision of a piece but are also capable of creating lively characters that interact on stage in a credible way. This may sound simple, but there are few directors who put emphasis on both.

How important has been it for you to put your own stamp on things? At Komische post-Kupfer, and Zürich post-Pereira, audiences & company personnel tend to have strong opinions about “the new person” and what they perceive he/she will bring.

I had the advantage that my two predecessors had been in office for over twenty years. The situations were due for change, which was also noticed by the media. In the case of Komische Oper, however, it was a difficult task, since the necessary changes were not only related to the aesthetics of the productions, but above all, to changes in management, such as the establishment of reliable controlling structures, modern marketing and much more. The introduction of such new structures always causes fear and resistance in a company, especially if one regards the Komische Oper as the former flagship of East German music theatre. Keeping the project on track was much more difficult than expected, but in the end, our efforts paid off and when I left I was able to hand over a much more efficient Komische Oper to my successor.

Artistically, my main goal (at KOB) was to improve the musical quality and expand the actual theatrical language of the theatre, which was previously more like a showroom of the responsible director. My approach was to form a group together with strong colleagues who all followed a similar philosophy, which, in turn, would shape a new aesthetic of the house on a larger scale. We were fortunate to have the young and promising Kirill Petrenko as chief conductor and — perhaps even more fortunate for the house — I found Barrie Kosky, who had previously only worked in Australia, as one of our regular guest directors. I was glad that, nine years later, he took over the company as my successor.

In Zürich it was more a question of restructuring production processes by reducing the number of new productions from twelve to a much more reasonable, but still quite high, number of nine productions per season. My predecessor focused more on conductors than on directors. So I was able to introduce a new and interesting group of exciting directors who had never worked here before. The directors were surprisingly well received by an audience that proved to be very curious and enthusiastic.

What’s the role of politics in art for you? Your production of David et Jonathas, for instance, has a very affecting subtext which seamlessly blends the personal & the political.

The theatre has always been concerned with conflicts between the individual and society. Even though our societies have developed strongly towards individual freedom, certain conflicts remain timeless and return with each generation.

As a director, when you try to transform the original scenery into something new and contemporary, you have to be very careful and consider every possible aspect that might lead to contradiction in your own concept. If you make a wrong decision, the work will resist. So every production is a new adventure.

Fellow Hungarian cooking question: to cook goulash in the oven or not? I do this, to very nice results.

Goulash in the oven? Never thought or heard of it, but it sounds intriguing though. I have to try it next time.