Photo: Lena Kern

The opportunity to see the worlds of art and music joined live on a stage is always a treat, whether it’s with William Kentridge’s production of Alban Berg’s Lulu at the Metropolitan Opera, or Barbara Monk Feldman’s Pyramus and Thisbe at the Canadian Opera Company. Stimulating intellectually, such integrations offer the additional possibility of emotional contemplations and experiences that reach past the limits of language.

The history of blending art and music is, of course, very long and encompasses total creations, notably Stravinsky’s 1951 work The Rake’s Progress, which was inspired by a series of eight drawings done by William Hogarth between 1732 and 1734; they chart the decline of innocent Tom Rakewell, who comes to London and is drawn into a world of debauchery, debt, and personal destruction. Stravinsky had seen the drawings as part of an exhibition in Chicago in 1947, and, together with poets W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman, created a sonic landscape that vividly captures the vitality of Hogarth’s work while simultaneously exploring vice, loss, and vulnerability. The Rake’s Progress premiered at Teatro La Fenice in Venice in 1951, before productions in Paris and New York; it was also part of the premiere season of the Santa Fe Opera. The text, by Auden and Kallman, is arguably one of the richest in the repertoire, but like the music, it’s dense and requires deft listening. Those aren’t bad things, by the way; as you’ll read, perhaps should be more encouraged in our overloaded, insta-hype culture.

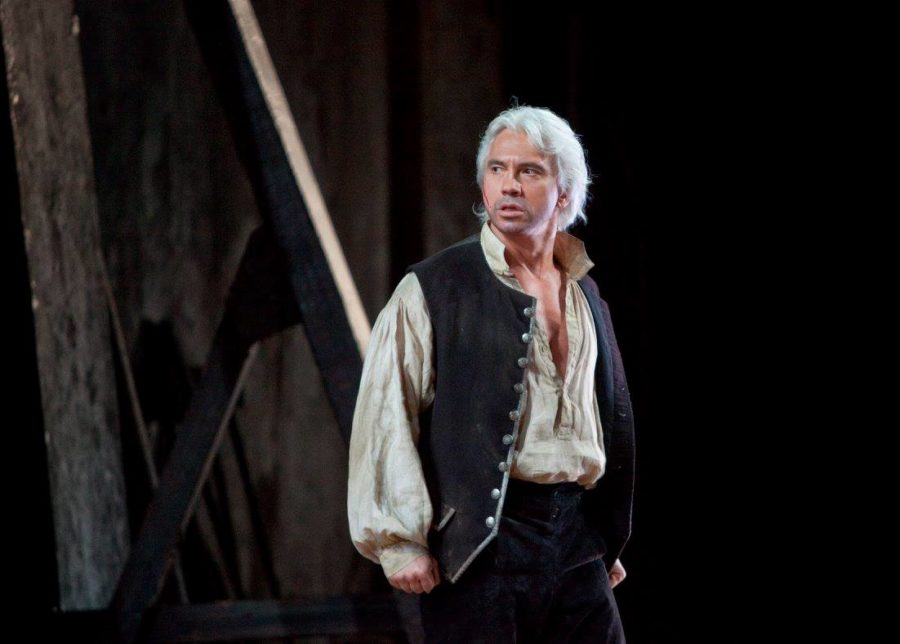

Topi Lehtipuu as Tom Rakewell and Matthew Rose as Nick Shadow in the 2010 production of “The Rake’s Progress” at Glyndebourne. Photo: Mike Hoban / Glyndebourne / ArenaPAL

This weekend the London Philharmonic Orchestra presents a live in-concert presentation of the work, featuring tenor Toby Spence as Tom, soprano Sophia Burgos as Anne Truelove, and bass Matthew Rose as Nick Shadow. They’ll be performing under the baton of Vladimir Jurowski, who led the work in 2010 at the annual Glyndebourne Festival Opera (where he was then-Music Director), in a storied production originally first presented in 1975, which featured Rose (as Shadow), Topi Lehtipuu as Tom, and Miah Persson as Anne. Designed by artist David Hockney and directed by John Cox, the production has toured extensively, and is a beloved part of Glyndebourne history. Smart, funny, and scary, this pretty production was my initial way in to its world; between it and a various recordings, I found this Stravinsky demanded great amounts of time, attention, patience, and care, much more so than many of his other works. Those qualities were heightened and found a natural (and dare I say, surprisingly comfortable) outlet when I was heard portions of it live at an LPO rehearsal earlier this week. The Rake’s Progress is, more than many operas, one that needs to be experienced live to be fully appreciated, providing a visceral experience that goes far past its decline-in-fortunes narrative. Tom’s loss, especially of his true love (pun intended), takes on a wholly real, and wholly passionate, sound. Equally striking is the unrepentant sensuality of the score, between the bronzen throb of basses and horns, the gossamer-like delicacy of violins and woodwinds, and ethereal (if utterly precise) vocal lines, The Rake’s Progress is as rough as it is poetic, as funny as it is sad, and as real as it is fable-like; it’s art and life joining, in a deeply satisfying integration of flesh and spirit.

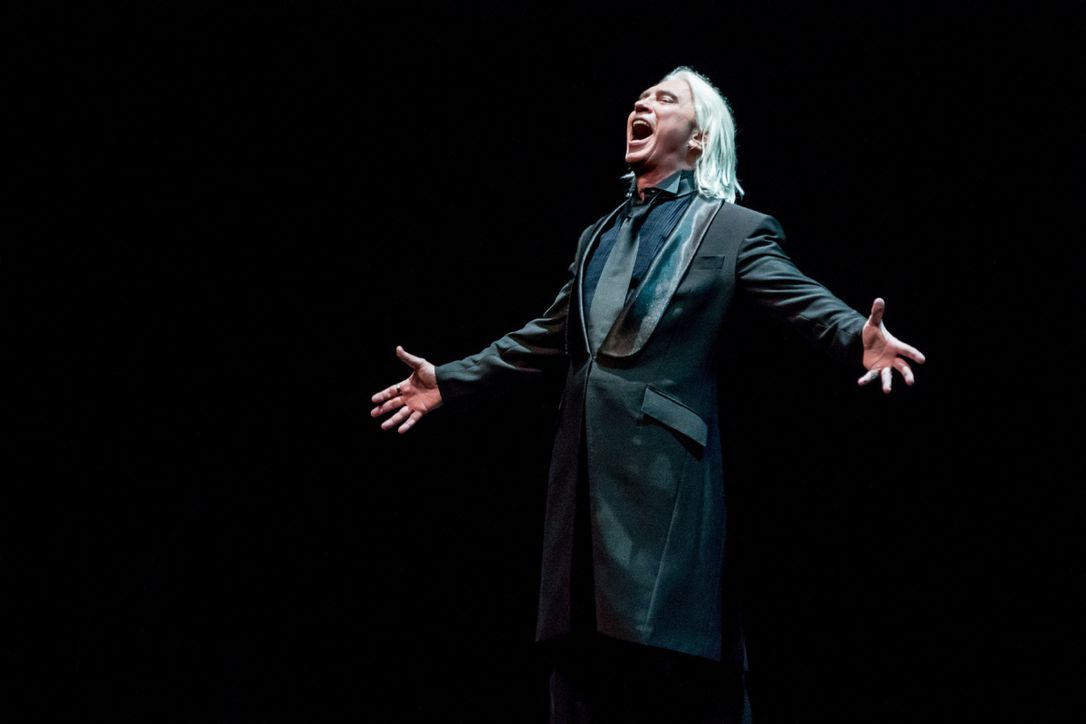

This is something I sense Matthew Rose knows and appreciates about the opera. We spoke last year about his work with the Scuola di belcanto; since then, the English bass has been named Artistic Consultant to the Lindemann Young Artist Development Program at the Met. He just wrapped up performing in two Puccini works in New York, La fanciulla del West (opposite tenor Jonas Kaufmann) and La bohème, and is scheduled to be in a Royal Opera House production of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godounov next summer. Between then and now, Rose appears at Opera Philadelphia as Bottom in Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (something of a signature role of his) and will also be performing with the London Symphony Orchestra and the BBC Symphony Orchestra. Rose is notable not only for his incredible vocal flexibility (his repertoire includes Baroque, belcanto, and contemporary works) but for his immediacy as a performer; there is a palpable sincerity to his work, a sense of urgency, and depth of true feeling. This applies every bit as much to the character of Nick Shadow (the actual devil in disguise) as it does to poor old Leporello (servant to Don Giovanni), the role I last saw him perform live onstage. I was keen to get his thoughts on the work itself,as well as the ways it’s perceived, and how those perceptions have played into contemporary programming choices. His responses were passionate, thoughtful, and hugely informed by a balanced sense of keen artistry and quotidian approachability, with large splashes of humour. Rose may be singing a villain this weekend, but I think it’s fair to say he’s one of the good guys.

The third of Hogarth’s paintings in “A Rake’s Progress” – The Orgy: The Descent Begins. (Photo: Sir John Soane’s Museum London)

What would you say to someone who’s new to The Rake’s Progress?

It’s very, very intelligent, and very intellectual. (The creators) put this thing together based on pictures by Hogarth, creating a whole story in a very intellectual way. It’s not Traviata — you have to really do your homework to understand what every sentence means. The Hockney production in Glyndebourne I’ve been lucky to do is so illustrative of what is happening — it is so accessible, which is why it’s been such a success.

Experiencing it live also makes it accessible, because one can clearly sense how immensely powerful and detailed the score is.

It’s the whole thing: seeing someone’s life go from one thing to another entirely, as this does. Tom’s this very happy, innocent young man who goes completely insane and dies in the end. It’s a very sad story, and Stravinsky’s music is so illustrative, and so appropriate for the time and to Hogarth. It’s brilliant he decide to do this.

The sensuality of the music can be surprising at points for newcomers.

Yes! And every single bit is exactly what it needs to be — the music is so brilliantly descriptive, some bits are so beautiful, (like) the way he uses the two voices (of Tom and Anne). There are also bits with Tom and Nick Shadow, at the end of their card game, where they sing a duet, and it’s very hilarious — the way he uses angularity and harmony is so clever.

There’s so much dramatic momentum within the musical lines as well.

Completely, though somehow it’s not quite become the great ticket seller I guess we all think it should be, but we get to spend hundreds of hours preparing it, so if audiences are able to have the same understanding as they did for the Hockney one, that would be good indeed.

Photo: Benjamin Ealovega

John Cox has said this is “an English opera written by a Russian composer” — what do you make of that?

That’s exactly what it is. As Vladimir says, there’s bits where Stravinsky quotes Tchaikovsky and Russian folk music; it’s very influenced by the Russian thing and classical music thing, and Kallman, who was American, and Auden, who was English, were putting the text together with that, so it’s an amazing collection of people and ideas. Shadow is the person who makes this story happen: he takes Tom out of this innocent place, and puts him in this situation which is opposite to that, and his life becomes worse. It’s interesting… it’s evil defeated, but not completely defeated.

He is Tom’s actual shadow…

They talk about that, don’t they — it’s his alter-ego in a way.

… but the serious stuff is balanced by comedy.

It can be done funny or sinister; it’s this brilliant script you can play with in many different ways. I think Kallman took on persona of Anne, and Auden did all the other bits as they wrote this. You have to trust what they and Stravinsky have given you, and use your own imagination too.

Photo: Lena Kern

How much do you think that sense of imagination applies to programming these days?

Who knows… people are being more and more conservative about what they’re doing, which I think is worrisome for our art form if this goes into the future. We have to believe in opera, and do it in brave ways. If you do very general, safe repertoire, in a very safe way, that won’t do anything for anyone.

Administrators would argue that those programming choices are not being made now because auditoriums are having trouble filling seats.

Yes, and they think they’ll solve that problem by programming safe stuff that won’t challenge anyone, but this art form is challenging, it’s not easy and it shouldn’t be easy. That’s the great thing about it: you are given so much information at once, and you can take so many things out of it, and perceive and experience it so many different ways. You can take it as a film and just sit back and watch, or you can think about the music itself, or whatever — it’s a great thing.

Some past productions of The Rake’s Progress made it about pretty pictures and wigs and corsets and, I think, contributed to the way it is perceived in some quarters, as this costume-heavy, non-tuneful Anglo-Russian piece.

It’s none of those things though; it’s very dangerous and sexy and brilliant. We shouldn’t be scared of these things; audiences should know about them. Also the way things seem to be going in terms of marketing and selling, you now have to have the right star — and these are people who won’t be singing things like this, or Peter Grimes. Art galleries can get people to see art of all different kinds of art, but at the same time we’re scared about cutting people off opera with new ideas; one art form can somehow do it and yet… maybe we need to help people understand what this is.

… while not dumbing it down, I would suggest.

You don’t need to dumb it down. Music is being taken out of schools and out of the core curriculum of education, and it’s a shame for our industry. If people are educated to know about stuff, then they can appreciate it, and why shouldn’t they know and appreciate this kind of thing?