When people discover that I lived in Dublin many years ago, I am always asked, since I have no Irish ancestry or family, why I chose to live there.

Romantic as it sounds (and romantic as it was at times), it’s because so many of the artists I admired in my youth were from Ireland; some chose to stay, some chose to leave, but I felt, as a young woman hungry for art, adventure, and love (and some magical combination therein), that it was important to be in the place of my artistic heroes and heroines, as if by some magical osmosis their genius might seep into my own work. I was fortunate to have spent good amounts of time working with and around artists of all kinds during my time there, and though it wasn’t quite what I’d been expecting, to quote Danish photographer Krass Clement (who himself spent a good deal of time in Dublin in the 90s), “I was a bit scared, but also drawn to the atmosphere.” Amen.

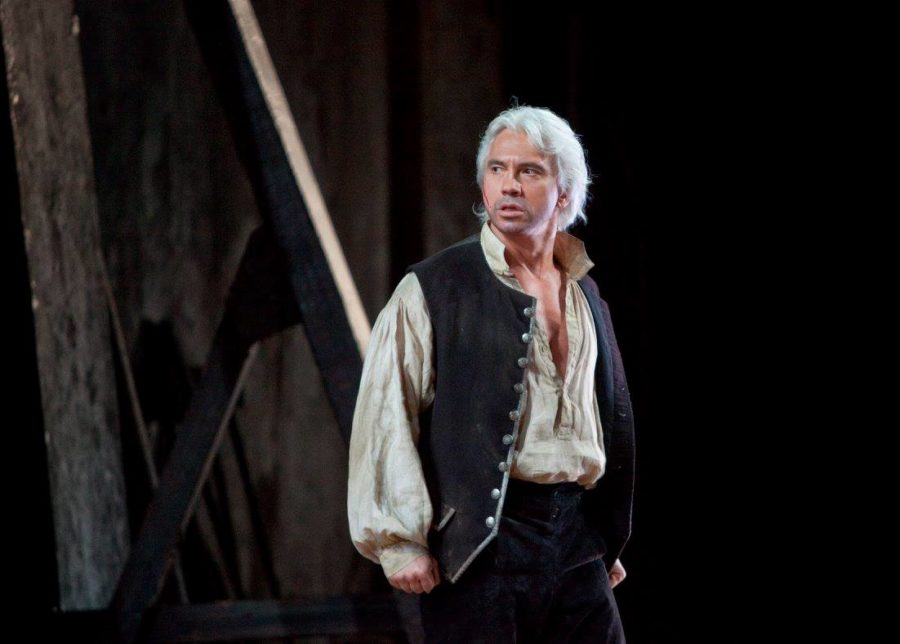

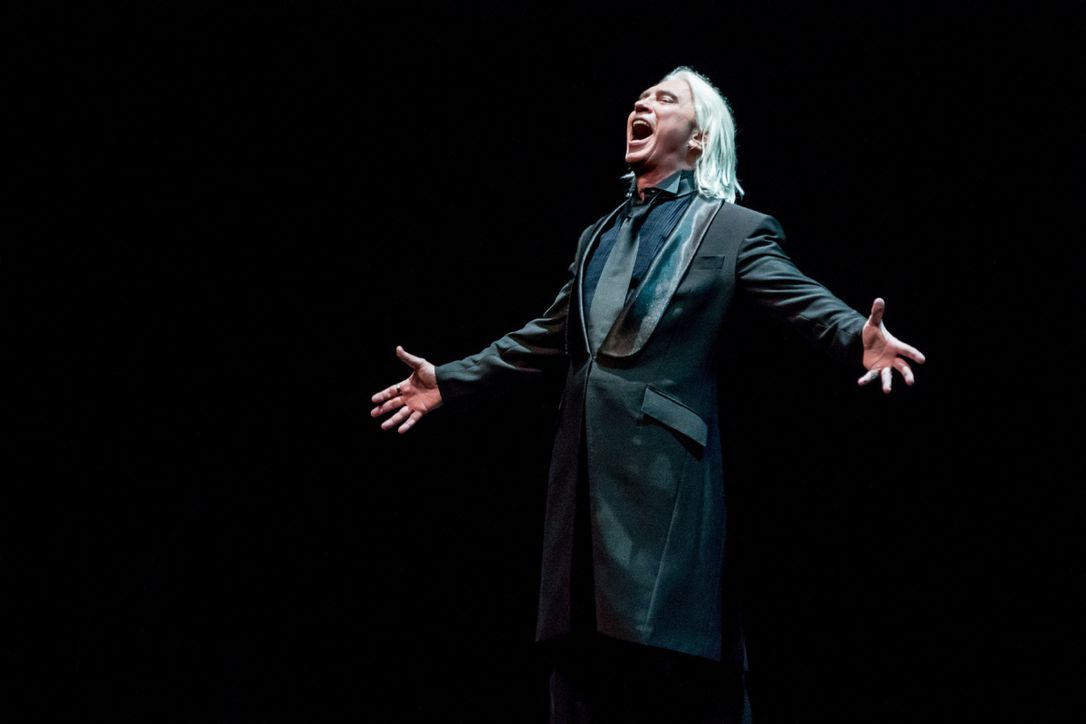

I seriously contemplated a trip to Ireland on my way back from Berlin recently. The timing meshed beautifully with the last third of the Wexford Festival Opera, an fest I have long wanted to attend, and which holds particular fascination for its blend of Irish culture and rarely-done work by famous composers. One event, The Thomas Moore Songbook, especially caught my interested. I’ve loved the work of Moore for many decades; the 19th century writer was one of the figures firmly in mind when during my initial move to Dublin decades ago. As my exposure to the music, movies, literature, theater of Ireland expanded, I became especially fascinated by such a small country, with such a difficult and very painful history, producing so very many great artists of all stripes, some wildly divergent in terms of their thoughts and feelings around the notion of Irish identity. Moore was one of the very first widely-acclaimed Irish artists to examine this question in a way that was inspiring, enchanting, and important, all at once. His work seems more important than ever now, in light of current news around borders and Brexit.

As well as being an acclaimed singer, songwriter, poet and entertainer, Moore (born in 1779) led an incredibly interesting, accomplished, and occasionally tragic life; he was one of the first Catholics admitted to Trinity College Dublin, had a brief stint living in Bermuda, and outlived all five of his children. The Poetry Foundation (who publish Poetry magazine) describes him as “a born lyricist and a natural musician, a practiced satirist, and one of the first recognized champions of freedom of Ireland.” His best-known work is Irish Melodies (1808-1834), which came to span over ten volumes and cemented Moore’s reputation in the poetry/music worlds. Composers (including Berlioz) set nine of them to music, and the works were translated into several languages including Czech and Hungarian.

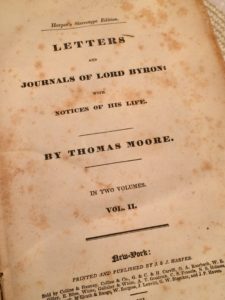

Volume 2 of Moore’s biography of Lord Byron. (Book and photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

Moore was also good friends with Lord Byron, who described various Moore works as his “matins and vespers.” The two had a long association, and Moore wrote a biography of his famous friend (who died in Greece in 1824), one Mary Shelley particularly admired. My intense love of the work of the so-called “dangerous-to-know” poet in my university days led me to Moore and made me a forever fan. This love expressed itself most clearly via loss; when a very close friend of the family’s, passed away in the late 1990s, my grieving mother asked me what should be carved on his gravestone. With nary a hesitation, I choose a few passages from a poem of Moore’s, words she loved. When my mother herself passed away in 2015, I couldn’t imagine the words of any other poet on her gravestone.

Wexford wasn’t in the cards this year, alas, but when I return to Ireland, it will be for a lengthy visit; there’s so much to see, to rediscover, to reconnect with and to explore anew. The Wexford Festival Opera is at the top of that list, and I am hoping there will be more of Moore’s work presented — that is a given if Una Hunt has anything to do with it. Hunt is an accomplished broadcaster, musician, coach, and scholar, and is a leading authority on Irish music history, particularly within the realm of forgotten composers. She has been at the forefront of the new Archive of Irish Composers at the National Library of Ireland and has taught at many of Ireland’s most prestigious music academies. She was Executive Producer of My Gentle Harp, a six-CD compilation (released in 2008) that is a complete recorded collection of all 124 songs from Moore’s Irish Melodies. In 2010, she presented the Melodies at Carnegie Hall (to two standing ovations, no less) and a year repeated the concert in Russia as part of the unveiling of a sculpture honouring Moore at the University of St Petersburg. Along with extensive publishing and performance work, Una has also produced a number of documentaries for Irish broadcaster RTÉ, including a tribute to French composer tribute to Claude Debussy.

The Thomas Moore Songbook was a huge hit at this year’s Wexford Festival Opera; both of its presentations sold out, something Una wasn’t surprised by, but, as you’ll hear, led to more questions, and more opportunities. As you’ll hear, Una has very strong opinions about the role Moore has played in Irish culture as well as identity. Why should you care about Moore? What does his work say to us now? How can a country forget (and/or ignore) its classical composers entirely? Blame not the bard...