There’s a simultaneous abundance and lack to summer. Yes, there’s light and heat, but lately I can be found working (or trying to work) in a darkened kitchen – barefoot, makeup free, messy-haired – listening intently to live broadcasts from Bayreuth, occasionally glancing through blinds to a barely-green garden and rows of sleepy doves parked in the shade. One feels guilty trying to hasten an end to summer’s pleasanter aspects (cerulean skies, reasonable warmth, scant clothing) – but oh, the autumn, with its jewel-like colours, cool days, cooler nights, its promise of structure through the coming months – they are not only welcome but greatly anticipated. The start of the 2024-2025 classical/opera season may be a few weeks away, but they feel closer than ever. Hopefully this overdue reading list will tie my readers through the remaining weeks of summer until regular interviews return once more.

First up: the Berlin Philharmonic is back on August 23rd. This season features Wolfgang Rihm as its Composer-In-Residence. Rihm, who first worked with the orchestra in 1977, sadly passed away on July 27th; he was 72. News of his passing inspired many tributes in the German music world, including a richly detailed feature at the Berlin Phil website. Many remembrances underlined the composer’s refusal to be constrained by dogma. Artistic Director of the Lucerne Festival Academy since 2016, Rihm composed over 600 works, including a number of operas that reached well across specific genres and styes. His opera-monodrama Das Gehege premiered at Bayerische Staatsoper in autumn 2006 and was later presented at La Monnaie in 2018 as part of a double bill with Luigi Dallapiccola’s Il prigioniero directed by Andrea Breth and conducted by Franck Ollu. Baritone Georg Nigl (the “prisoner” of the latter production) worked with Rihm on numerous occasions and appeared as the lead in Rihm’s one-act chamber opera Jakob Lenz (based on Georg Büchner’s 1836 novella) at La Monnaie in 2015. Nigl told BR Klassik‘s Bernhard Neuhoff recently that “Ich habe mir durch Wolfgang einen Kosmos erschlossen, der mir – wenn ich das über mich selbst so sagen darf – den Weg geebnet hat, ein künstlerisch denkender Mensch zu werden.” (“Wolfgang opened up a cosmos for me that – if I may say so about myself – paved the way for me to become an artistically minded person.”) German composer/pianist Moritz Eggert posted a touching a tribute at his website (Bad Blog of Musick) noting Rihm’s incredible prolific creativity, his support for his colleagues, and that “Herz schlug dabei stets für das Ungewöhnliche, Besondere und Unkonventionelle.” (“His heart always beat for the unusual, special and unconventional.”)

Earlier this year musician-dramaturg Arno Lücker delivered a music lecture in Vienna in which he shared his ideas behind the process of writing about 250 female composers, contemporary and historic, strictly classical and not-so-classical. His selections, published over four years by Van Musik, ended with 12th century polymath Hildegard von Bingen (Lücker chose not to hew to formalities around chronology) and included Margaret Bonds (1913-1972), Undine Smith Moore (1904-1989) and Florence Price (1887-1953). His lecture, transcribed in full at Bad Blog of Musick, concluded with a reminder of the link between education and transformation:

… make sure you include female composers in your music education formats. We can’t just tell the young people out there, for the thousandth time, how great Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is. There is an urgent need to catch up in this area too.

(Arno Lücker, Bad Blog of Musick, 8 June 2024)

I wish he’d written a bit more on the need for a greater breadth in education (I write this as someone who examined the Ontario music education curriculum for elementary schools in detail earlier this year) – but hopefully Lücker will offer some form of follow-up.

The need to “catch up” was in my mind as I read observations by Slipped Disc founder Norman Lebrecht on the diminishing quantity (and quality) of classical coverage in The New York Times. (“The Decline and Fall Of Classical Music at The New York Times“, Slipped Disc, June 27, 2024) The traditional media (as symbolized by the NYT) once played, and still frustratingly plays, a major role in shaping public perceptions and ideas around culture, as much as shaping the industry in which it operates; coverage, criticism, and updates were all once regular features of classical news coverage. With the rise of digital much of that changed, especially in terms of the shortening of features, the hewing to algorithms, and the concern over stepping on advertiser toes; yet another layer of challenge came via the coronavirus pandemic, diminishing already-tiny budgets and concentrating power and influence – thereby shrinking cultural discourse around classical/opera in the process. My own feeling is that the industry as a whole (media + agencies, artists, promoters, publishers, houses, educators) needs a giant catch up of its own. Intelligent solutions need to be found for those on every side of the classical wheel. (Step 1: classical/opera-specific sites, please pay your writers.) Looking to and/or relying solely on the siloed audiences of a siloed legacy media feels not only outdated but vaguely absurd. Au courage…

Speaking of courageous: this is an intriguing reimagining of the beloved ballet La Bayadère (“Pas de Deux With Cancel Culture“, Chava Pearl Lansky, JStor Daily, June 12, 2024). In place of the highly-romanticized “exotic” aesthetic meant to conjure 19th century India, a new version sets the action within the cinema world of 1920s America. The work, called Star On The Rise, premiered at Indiana University in Bloomington in March and was spearheaded by musicologist and dance historian Doug Fullington (who counts the ability to read Stepanov notation among his many accomplishments) and educator and administrator Phil Chan, the co-founder of advocacy group Final Bow for Yellowface. Rather notably, Star on the Rise retains Petipa’s steps. In a response to an op-ed published earlier this year by Dance Australia editor Karen van Ulzen in which she stated La Bayadère was “in danger of being cancelled” Chan stated:

I don’t advocate pulling works out of repertory just to be”politically correct”, but I believe we do ourselves a disservice by presenting racial caricatures from over 100 years ago. I advocate for replacing caricature with character – with the goal of greater integrity instead of a “cultural accuracy” no outsider’s vision can really claim.

Before folks clutch their pearls about changes, just remember we do this all the time with Shakespeare and in opera. Nothing has to be lost by reimagining an old story with a new location if we first understand the original context and how that influenced certain artistic choices.

(“How NOT to cancel ‘La Bayadere’“, Phil Chan, Dance Australia, 23 March 2024)

The challenge of the either/or in live presentation (i.e. staging a crowd-pleasing spectacle versus attempting a deeper dive) is one companies and creatives alike have attempted to wrestle in various contexts, but sometimes (often) context goes out the window. Vandalizing art, as happened in Bregenz recently (“Vandals Attack Billboards Designed by Artist Anne Imhof“, Jo Lawson-Tancred, July 24, 2024) and wiping out the name and work of influential Ukrainian theatre artist Roman Viktyuk (“In Moscow, they finally got rid of Ukrainian Viktyuk’s theater“, Marina Buzovska, Pragmatika, July 10, 2024), which are certainly examples of “cancel culture”, point up issues of control, power, propaganda, presentation and reception within the socio-artistic sphere.

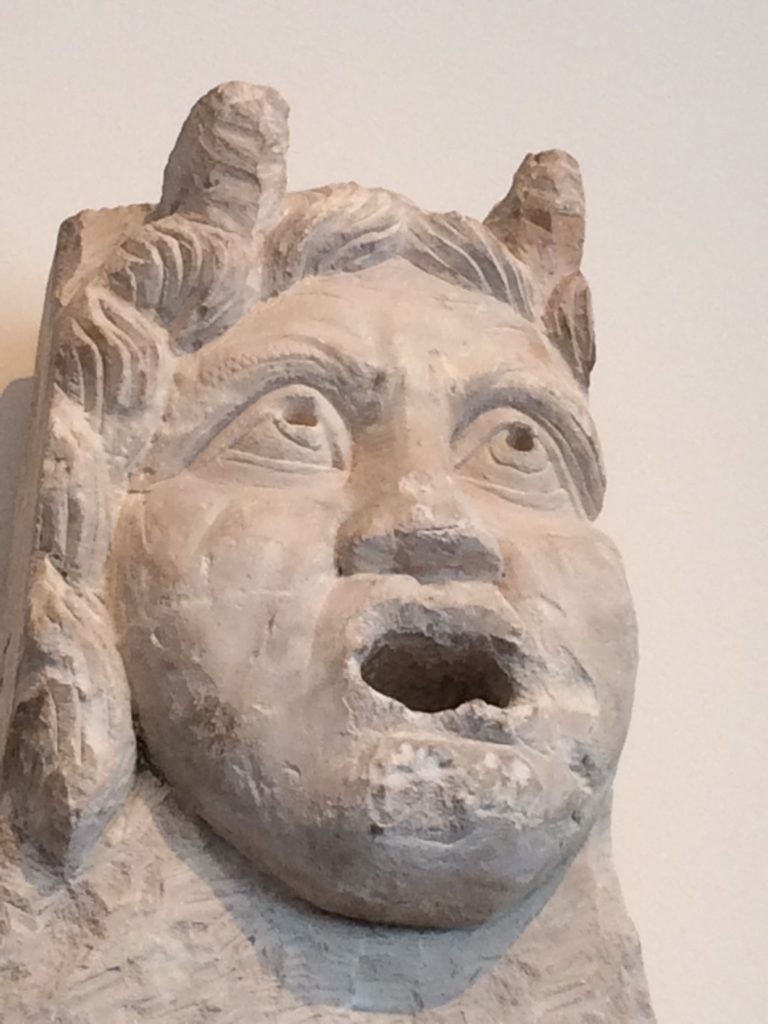

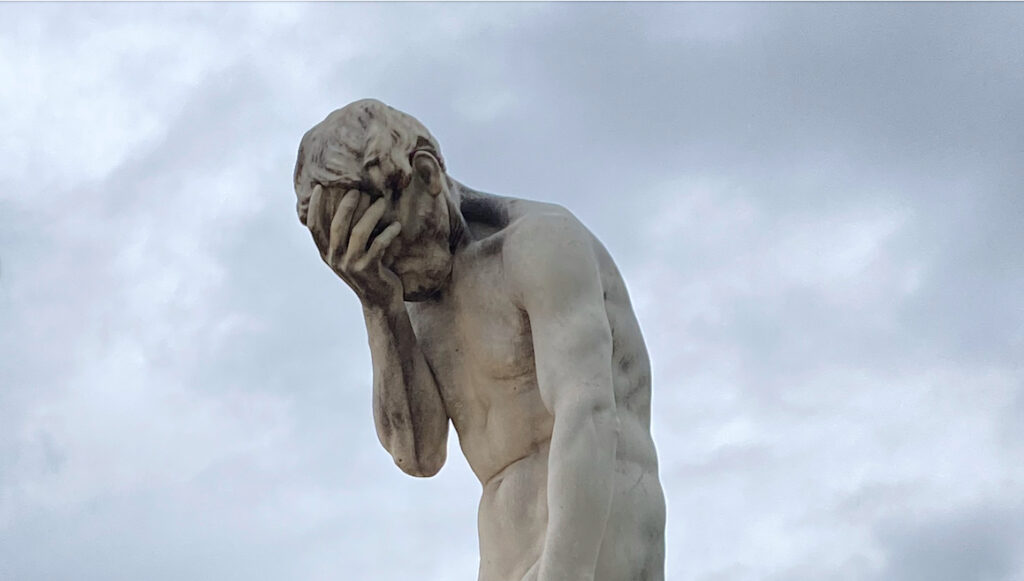

Henri Vidal, Caïn venant de tuer son frère Abel, 1896; Jardin des Tuileries, Paris. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without express written permission.

Another layer of challenge comes in recognizing and dealing with abuses of power; questions arise as to how certain artists should be viewed, engaged with, and/or covered in light of exposure of such abuse. Earlier this summer it was reported that American painter Kehinde Wiley, facing multiple allegations of sexual assault, had several upcoming shows cancelled. The National Coalition Against Censorship released a statement in June, one subsequently answered by statements from accusers. (“Kehinde Wiley’s Accusers Respond to Concerns Over Canceled Museum Shows“, Valentina Di Liscia & Maya Pontone, Hyperallergic, June 27, 2024) The recent (semi)fall of the mighty (i.e. François-Xavier Roth and John Eliot Gardiner) notwithstanding– one wonders at the role of context in such cases: how does specific knowledge of artists’ behaviours impact enjoyment/understanding/appreciation of their art? What responsibility do organizations bear in presenting their work? Who decides what is contentious? What responsibility exists to past/present victims? Should there be any? What is the role of sensitivity? Who benefits? Who pays? That last one is especially important, in both literal and figurative senses, and can serve to create (and feed) a toxic brand of resentment.

In an individual sense, one wonders at the vast and largely invisible network who help to power the art world, those who endure abuse and ensconce others within their positions of privilege that perpetuate abusive practices. A fascinating piece posted at Hyperallergic last month explores this question within a socio-historical context, examining the many unknown scribes who were responsible for the first transcriptions of biblical text. Writer Sarah E. Bond opens her historically detailed article with a brilliant distillation of the “lone genius” image that powers perceptions of culture, even now:

Art and literature work in tandem to fortify myths of single-handed brilliance, creating a reverence for the proverbial “solitary genius.” Romantic depictions of the ancient author toiling away at his desk or the medieval bishop writing letters while alone in his study reinforce and reinscribe the aesthetics of authorship as a lonely, inspired endeavor. In truth, these are far from authentic depictions of true authorship.

(“The Enslaved People Who Wrote Down the New Testament“, Sarah E. Bond, Hyperallergic, July 28, 2024)

Conductor Hannu Lintu recognized his assistant, James S. Kahane, ahead of the opening of Bayerische Staatsoper production of Pelléas et Mélisande last month. More of this please, classical/opera world!

And less of this (way less – stamp this kind of thing out entirely, please): it was recently revealed that any artist working in Russia must adhere to the country’s new cultural policy, one tied to promoting/glorifying the war in Ukraine if they want any form of funding whatsoever. (“‘Everything from love to heroic death’: The Kremlin’s new cultural policy puts the war against Ukraine front and center in Russian art“, Meduza, July 24, 2024). The country’s recent prisoner exchange with the U.S., which saw the releases of Vladimir Kara-Murza, Ilya Yashin, Sasha Skochilenko, Oleg Orlov, and Evan Gershkovitch among others, seems particularly poignant given that immediate artists will be basically unable to explore the lives of these figures in any meaningful sense throughout creative media – unless a distinctly pro-Kremlin narrative is taken, that is. Many of the works being presented and performed by exiles now are filled with rage, and with good reason.

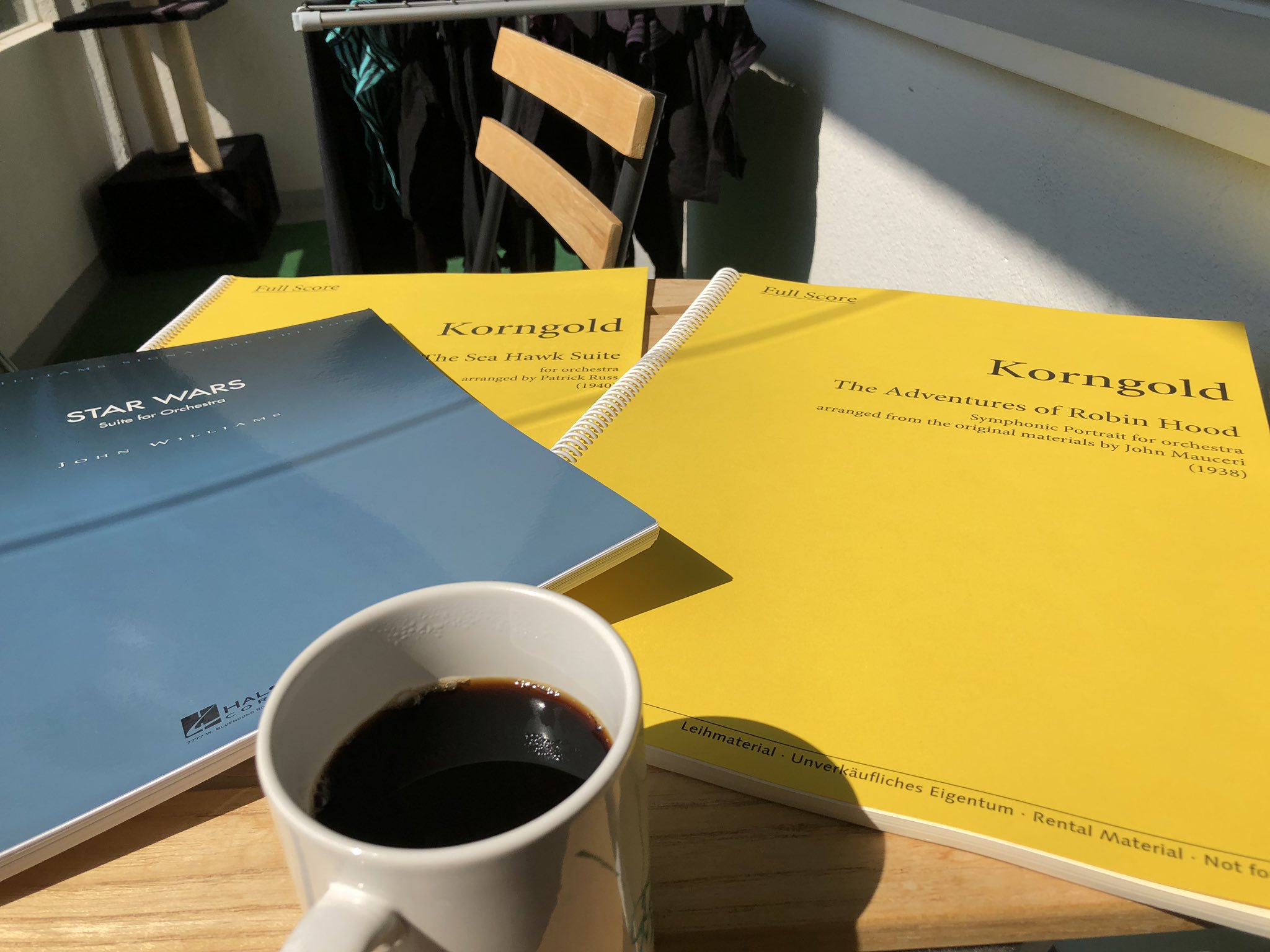

Rage, of course, can sometimes feel like the outer shell of grief. This year’s edition of the Edinburgh Festival features three works which deal with various aspects of grief. (“‘We want it to feel like a wake’: the Edinburgh Fringe artists exploring grief on stage“, Natasha Tripney, The Stage, July 29, 2024). Kelly Jones’ semi-autobiographical play My Mother’s Funeral: The Show, explores issues of class, grief, and privilege, while Look After Your Knees, created by Natalie Bellingham and director/performance-maker Jamie Wood, explores the difficulties following the death of a close relative – in this case, Bellingham’s mother. “My mum took up quite a lot of space in my life,” she says in the feature. Reading this I was reminded of the words of conductor Giordano Bellincampi in our conversation last year, when he was preparing to lead the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra (APO) in a concert presentation of Korngold’s Die Tote Stadt. “We have a lot of operas about death – in the sense of revenge and power,” he said at the time, “but we don’t have many about grief, how it is when people actually die.” Bellincampi will be leading the APO in a concert presentation of Tristan und Isolde on August 10th directed by Frances Moore, with Simon O’Neill and Ricarda Merbeth in the respective title roles, together with Albert Dohmen as King Marke, Katarina Karnéus as Brangäne, John Reuter as Kurwenal, and Jared Holt as Melot.

Speaking of teamwork: the fourth season of Prime series The Boys recently concluded. I wrote about the series’ literary-operatic corollaries in 2022, and it was interesting to read Inkoo Kang’s essay in The New Yorker earlier this summer (“‘The Boys’ Gets Too Close For Comfort”, June 26, 2024). Taking a less artsy if decidedly timely approach, Koo underlines the show’s embrace of a more blatant political commentary via the character of Homelander (who, for all the superhero trappings, is alarming familiar) and, along with noting how such embrace has risked turning off longtime fans, makes a salient point: “Even as (showrunner Eric) Kripke delights in the gruesome and the absurd, he advances a question that too few actual political actors seem to have asked themselves: How many norms and institutions are they willing to destroy in order to “win”?” A Faustian question indeed, and also a very operatic one.

Finally: the UEFA European Championship has wrapped up for another season – I watched the final with an unseen but very-heard audience of many windows-open neighbours. Shrieking with unseen strangers on a summer night: fun! Throughout the game my mind kept returning to this, captured on the very first weekend of the Championships in Hamburg; the voices, the coordination, the props, the theatre, the design, the choreography: … soc-opera?

Until September: read, listen, walk, think, smile… and remember the c-word. 🙂