December is a glum month. The cozy, communal nature of this time, reinforced by a combination of weather, occasion, social ritual, the marking of time and season, plus the digital signifiers that Surely Everyone Is Having A Better Time Than You, means, for those lacking family and/or firm social network, a keen feeling of being forgotten, whether it is true or not.

Oh, but the very many will (and do) say, we’re all so busy. Never has a word been more overused, and December is a good reminder of the ease with which avoidance is casually wielded – for fun, for comfort, and yes, for an understandable want of calm. Sometimes people, even the most popular, actually-busy, super-hyper-social ones, simply want to pull a Garbo. I appreciate that, as someone who often, pre-pandemic, felt the desire to leave hot, crowded rooms, the feeling that I was being smothered made smile-laden socializing difficult and stressful; usually I’d continue smiling and guzzle down a gallon or two of water. Such smothering feels more pronounced now, intro/extrovert labels be damned; one falls between, around, over, and under such easy categorizations, in this, the Age Of Omicron. I want to spend time… but are you boosted? Let’s have dinner… but can we get a negative test first? I’d love for you to kiss me but… ? Having viewed casual contacts with some suspicion over the years, lately I feel a deep gratitude for any miniscule crumb of kindness; amidst pandemic, little things become big things.

I was reminded of this earlier in the week when I received close to one thousand well wishes for my birthday. While I would have loved to have thrown a big party, or travelled (or ideally done both, as I had done in years past), reality dictates otherwise. Living alone as a freelance writer and adjunct Professor means being ever-conscious of illness and its effects, financial and social, as much as physical. Thus does staying in and alone become less a choice than an exercise in logic. Choosing solitude, when one has the absolute privilege of people around them at any given moment (and never let it be forgotten that having people around – partners, family, associates, work colleagues, friendly neighbours, pets – is a very under-recognized form of privilege), is far and away a different thing from solitude as a lived, actual norm. The few in-person conversations I’ve had lately are accompanied by a counterpoint of constant anxiety, wondering and worrying if I’m talking too much, too loudly, too quickly, pontificating and pondering, desperate to be heard, and desperately happy for this one (poor) individual to really be sitting across from me. I am, I fear, turning into the Crazy Old Woman cliche, minus (so far) the cats.

“You’re different, that’s for sure,” my mother used to say, furrowing her eyebrows and judging, for the thousandth time, how it was she, one of those hyper-social, popular, widely-loved, togethery-with-all-sorts, could have possibly birthed… me. The thing she perhaps didn’t see, or more directly refused to admit until the very end, was her culpability: a single, beautiful, cultured woman in a grey, artless, firmly conformist environment could not possibly be anything other than an outsider. The most powerful lessons are those done through osmosis, and her position as a divorced (and again, gorgeous, glamorous, artsy, social) parent in a bleak Canadian suburban had an effect – how could it have been otherwise? Such an upbringing screws in a keen sense of individuality, of the pain of being an outsider, and its strange, strangely-experienced joys. If, her reasoning went, everyone was to settle for being “dowdy” (her word), well… she’d be the precise opposite, and damn them if they hated her for it (they did). To hell with the cost to her daughter. Those costs were indeed great but sometimes there were benefits. I could show up most everyone who’d mocked me/pushed me over in the playground/thrown snowballs at my head with ribbons of intricate piano playing sounds that always impressed adults, namely teachers. It was a talent which sometimes got me out of boring classes and into the cool, quiet environment of a tiny teacher’s lounge that happened to have a piano; it was always a treat to be plucked out of class and be told I could, for an hour or sometimes two, practise to my heart’s content. I can still remember my shop teacher’s face when he heard me one afternoon, the way he stopped and stared, dumbfounded.

“Has your mother talked to anyone about putting you in the gifted program?”

They said no. I already tried.

His eyes widened, but he was silent. Years later I ran into other teachers from that elementary era, and all of them, oddly enough (or not), said: “You really should have been in the gifted program, you know. I mean, we all said that.”

It was at my mother’s insistence that I took some classes with the gifted group and felt that I was being ferociously judged, fiercely rejected, in a more brutal manner than usual. You’re not one of us you plain-spoken, poorly-dressed imbecile. I remember the silent stares, the quiet eyerolls whenever I spoke (which wasn’t often; I was terrified). I wasn’t smart enough for them (or something), I wasn’t unique enough (or something), my work was (apparently) unoriginal; thus it was back to the land of the super-normals (or something) where I clearly didn’t fit in either. I could not possibly be a part of their club, or so their behaviour implied, repeatedly. I recognized that same anxiety in speaking with various academics, authors, managers and musicians over the years, and I can clearly count the times I didn’t feel I was being similarly judged. Not smart enough; not unique enough; stupid, unoriginal. Back to the land of normals; rinse, repeat.

Snippets of overheard conversations my mother had with close friends arrived with the sound of her sighs. She just didn’t know what to do with me. What I loved was considered “too” weird, “too” outside, “too” daring, even for the woman who had, once upon a time, tried so hard to fit in with a world that wasn’t going to accept her either; I think it hurt her to see me making the same sorts of efforts, and with the same sort of results. Her efforts to gain acceptance within the teensy-tiny bubble of small-town Canada were never going to be successful; so too, for her artsy, anti-social, book-and-music-loving daughter who had a predilection for doing things in her very own way, who’d been told by the “special” folk she wasn’t “special” enough, who learned how to hide everything behind masks of makeup, dresses, heels, who became adept at distraction and diversion, who contented herself to be the entertainment, to inspire desire and derision, envy and confusion, and of course, ostracization, exclusion, isolation. To clench jaw and smile at rejection. To give a middle finger with a bat of the eyelashes. It became second-nature; it still is.

There were eyerolls when I’d exit my high school history class early on Fridays; I was off to then-dingy New York. My mother had a subscription to the Met Opera; it wasn’t as fancy as everyone thought – we had seats in the gods – but no one in our little town knew or cared about such details. We were being fancy, snooty, pretentious; I was perceived as uppity, absurd, self-important.

“Have fun at the opera,” they’d sneer.

“Have fun at the mall,” I’d reply, slipping on my faux-fur coat over my ugly grey uniform.

Really, it wasn’t a question of my believing opera was somehow “elite” – I never thought it was; looking around at the Met on any given night, I’d see all sorts, dressed in all ways, and it was nice to feel part of a community where we could all come together and talk about this thing we all loved. How many excited conversations did my mother and I enjoy at intermission and post-performance, with people whose fashions mattered so much less to us than that they could speak about x singer in y performance with z conductor; that, to us, was every bit as magical as what we had just experienced. How could any of my fellow students, in my crappy little town, possibly understand? I didn’t try to fit in with them; I used their cliched, outmoded perceptions of the art form I loved in a way that protected my own passions, musical ambitions included. Thus my teenage weekends weren’t filled with parties and dancing and snogs with boys I barely knew, but with the sounds of Tebaldi and Domingo and Pavarotti, dinners at little Manhattan restaurants (long since gone), trying on a much-needed new coat at Century 21, cocktails mixed in our hotel room before and after performances (my mother didn’t believe in mystifying alcohol), and oh, the happy expressions during and after every performance – the sighs, the exchanged looks, my mother’s quiet “aaach!” at hearing, or remembering various musical moments, sung or played. I hated coming back after such excursions; Monday morning became tearful. I did not want to face them.

“But we’ll be back in two months!” my mother would shout over her cassette of Maria Callas arias. “Put on some lipstick – you’ll feel better!”

Rejection and defiance are close bedfellows, as recent history attests; the constant feeling of being outside the perceived (usually strict) circles of perceived norms and related social interaction mean that head-tilting haughtiness, protective thought it may be, screws in the nails of an innate, proud different-ness which led, in some cases, to a terrible if perhaps predictable isolation. “If you send out the signals you don’t want to fit in,” pronounces the school principal in the 1986 John Hughes film Pretty In Pink, “people will make sure you don’t.”

“That’s a beautiful theory,” retorts Andie (Molly Ringwald), maligned for her low socio-economic status as much as the unique fashion sense inspired by it. I loved that movie when it came out, not only for its style (I had wanted to be a fashion designer for years and still find myself sketching ideas for outfits to events I’ll probably never attend) but for its poor-girl-wins-for-being-weird theme. It’s one that is proven more and more within the realm of pure fantasy as a woman moves through life without hitting the predictable marks, rendering her invisible (or close to it), a position which not all of us have quite made peace with. The rise of digital media has created an algorithmically-dictated hierarchy of worth and attractiveness based on a youth that can only be conveyed through the erasure of physical indications of living – of experience, of endurance, possible wisdom. Difference comes with even sharper edges (deeper wrinkles, as it were) when one hits a certain age and is without family or close community; thus is one thrown into the bins of fetishistic sex fantasy or angry frump, with little if any room for (or interest in) nuance and all the fascinations such variance can (or should) afford. I am sure many perceive there to be something quite wrong, that my too-haughty shell has led me here, that this is “the price” of such attitudes– a simple-minded calculation to smirk at. I didn’t expect my mother to die so young; neither did she. One of the last things she said to me six years ago (when she still had the strength to do so), was, “I’m sorry” – and it wasn’t just about that morning’s snappish behaviour, I knew; it was the same apology (the same words) uttered by my father at our final meeting eight years prior, an acknowledgement of wrongdoing that manifests on the face and in the eyes. I knew precisely what she meant, and she knew I knew.

“It’s okay,” I said, choking back tears. It had to be; she was dead three weeks later.

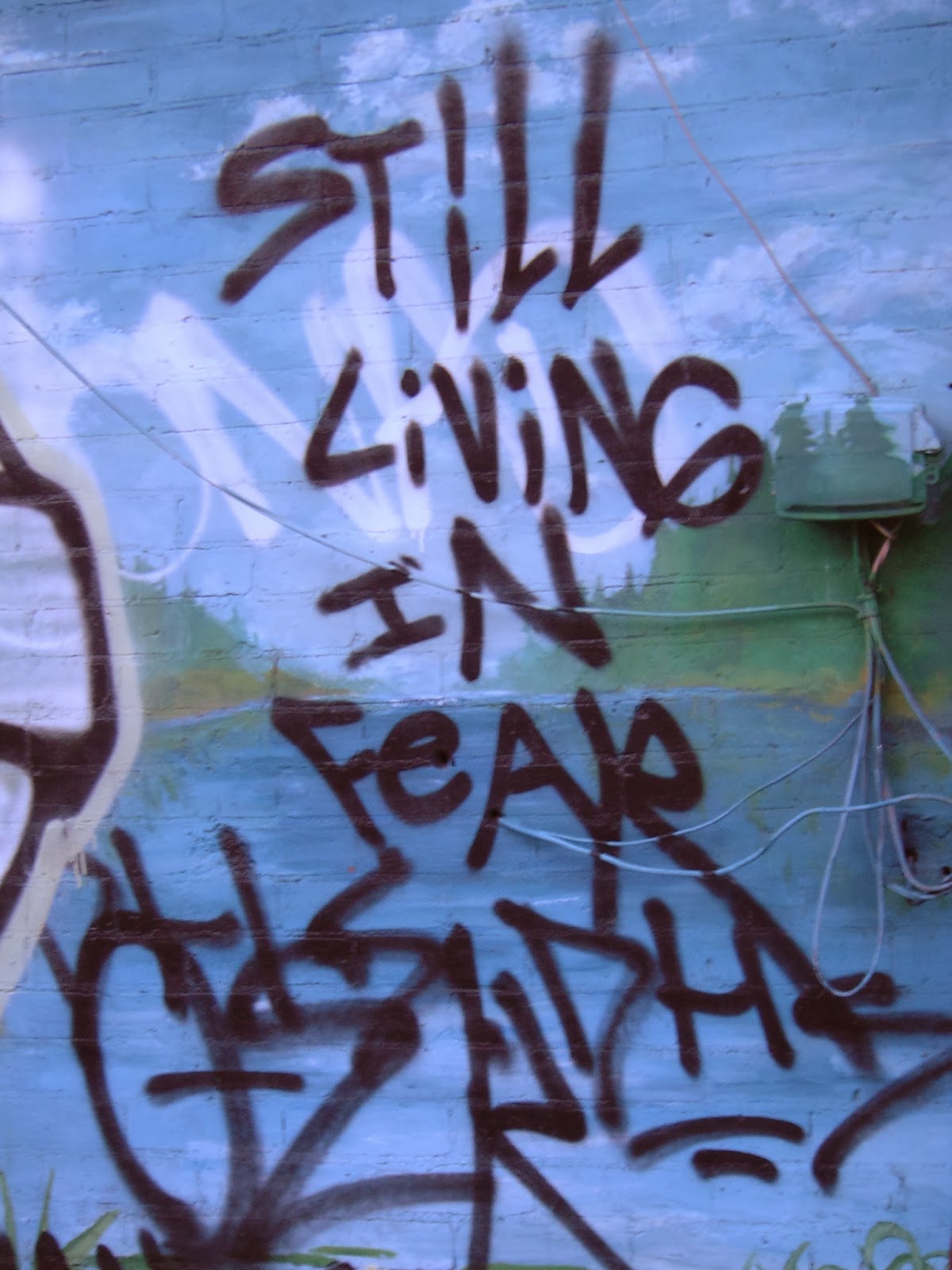

More than once I have written to close contacts that I don’t miss my mother, and it’s true, I don’t; that feeling changes in December, the most glum month, as I wrote, a month when being an outsider hurts in a way it doesn’t the rest of the year. Geography, and the cultural differences that such geography brings, can (does, in my case) make an immense difference, but of course there are a whole new set of circles and a far more knowable kind of separateness to be navigated, which is easier and more difficult, all at once. The feeling of being different never leaves, no matter the setting; it isn’t something to be celebrated, or indeed, something that should inspire any form of reaction at all. Different-ness, and its unmissable expression in life, can only be accepted, along with all of its itinerant branches, reaching like octopus arms across various facets of living, the one facet, which shows itself every December, is painful, for it is a reminder of lack. But so too is there reason to remember abundance.

The pandemic brought the worst of childish habits to the fore and social media gave such instincts a stage for amplification; recently I looked back on old postings (since deleted) with a mix of horror and fascination. Oh, the ways we continue to seek a validation we felt was always missing since childhood; oh, the means we have at our disposal to receive and encourage it. The performative aspects of social media have led to aspects of our private lives taking on the appearance of a shadow-play, stripped of the blood-and-guts messiness of real, authentic living. But oh, that real living is what is most missed; my mother made a fuss in December, the month of my birth, the month of her father and brother’s birth, the same month of their respective deaths. How to navigate such sadness with the miracle of giving birth (something I am told she never expected to do, which she did late in life, and amidst a hideous separation) – December was a loaded month for her, and it still is for me. Lately I walk around my tiny abode wishing for little more than the aroma of her annual baking: the almond crescents, the raspberry bars, the whipped shortbreads. Her frenzied gift-giving, not just to close contacts but to everyone in quotidian life – postal people, bank tellers, hairdressers, delivery drivers– was perhaps her own way to seek (and find) validation, to fill the perceived hole of her own outsider-ness, feel her presence was somehow, despite everything, valuable.

For every individual who took time to wish me a happy birthday this past Tuesday – to write on my wall, to send a kind note, to offer good wishes: thank you. Small things are big things – now, more than ever.