Lately I’ve found myself re-evaluating the past with all the complicated and sometimes ugly details of the present. It’s been an important and sometimes painful journey, for a variety of reasons both personal (disposing of photo albums, many of which were my mother’s) and professional (my slow if sure transition away from journalism). Through travels, research, readings, and various creative ruminations, I’ve come to appreciate just how deeply recontextualizing materials of the past can help us understand and appreciate new ways of being fully and completely present, however uncomfortable that may sometimes be; evolution is not, after all, supposed to be a comfortable process.

I suspect this is something Georg Katzer understood. The award-winning German composer, born in what is now Poland in 1935, was a pioneer of electronic new music in the German Democratic Republic. He founded the Studio for Electroacoustic Music in the 1980s, and made a career of redefining past to understand present, setting the stakes high for future modes of expression. The weight and influence of Europe’s shifting history through the decades lent him a ravenous curiosity for exploration of the past mixed with an enthusiasm for for redefining the present; he did so much with a twinkle in his eye as well rather than the furrowed brow of a serious artiste, which gives his work a discernible humanism, even amidst the plaintive bleeps and sighing bloops of works like “Steinelied I” (1984) and “Steinelied II” (2010). Listen to his wide-ranging oeuvre, which moves easily between lyrical brutality and brutal lyricism, and you’ll hear Bartok, Stravinsky, Lutowslawski and Zimmerman, as well as bits of Kraftwerk and Einstürzende Neubauten. Sounds brush, bump, groan, and grind against each other in ways that are, even many decades after their creation, gripping, contemporary, and theatrical.

Georg Katzer (from ensemble unitedberlin program)

That theatricality is readily apparent in “Szene für Kammerensemble” (Scene for a Chamber Ensemble), premiered in Leipzig in 1975. A smart work that embraces various meta aspects of music-making, Szene was, at its inception, a meditation (and, it must be said, a sarcastic commentary) on the bureaucratic nature of the GDR and its uneasy relationship to cultural life and artistic expression. The work, first performed in 1994, was presented by German chamber group ensemble unitedberlin last month at the Konzerthaus Berlin for their 30th anniversary concert. As the program notes state, the piece is “one of the representatives of “Scenic Chamber Music” or “Instrumental Theatre,” in which performative aspects of music production and linguistic elements came to the fore.”

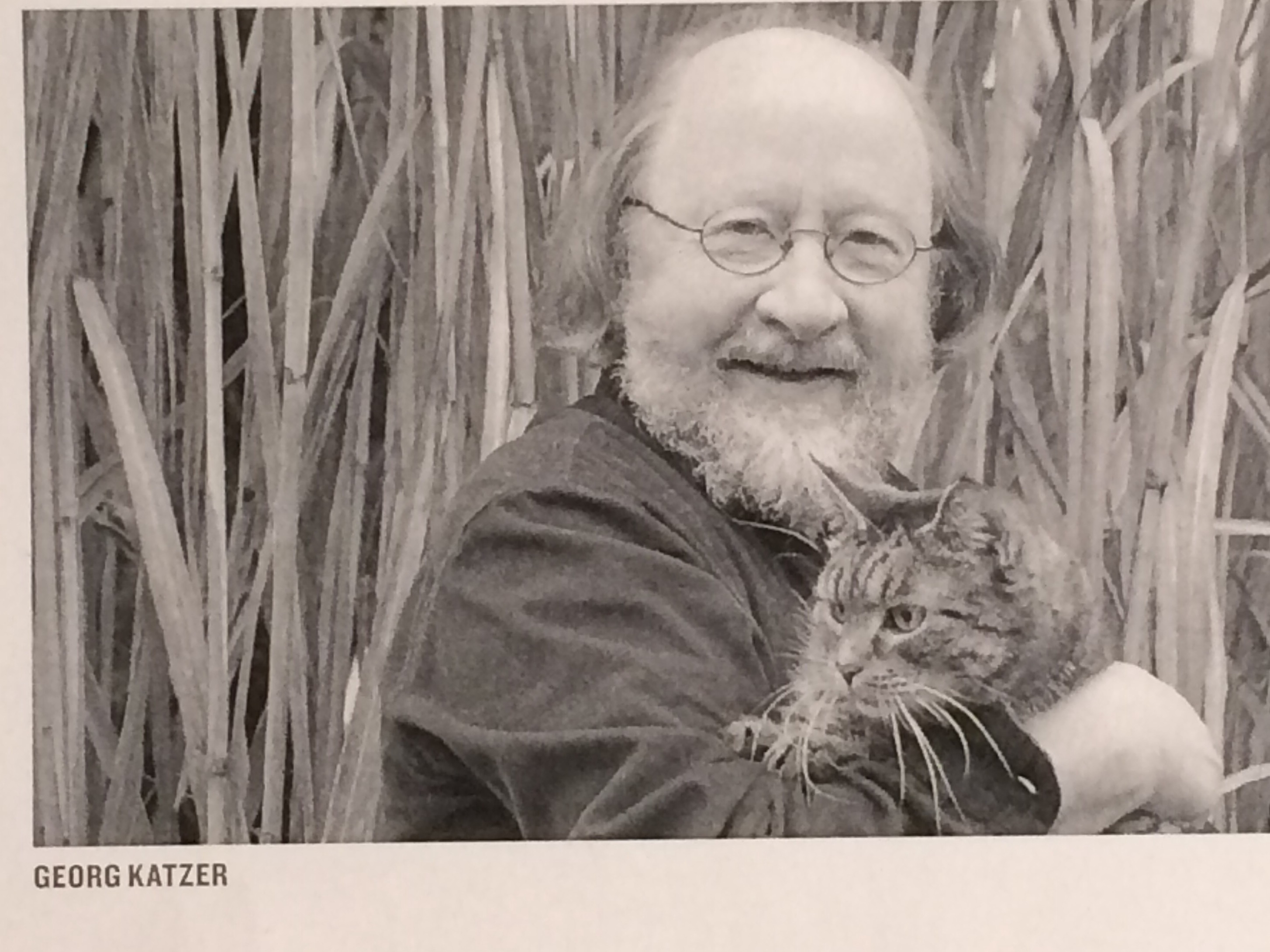

I’ve written about ensemble unitedberlin in the past (specifically in relation to composer Claude Vivier), and this concert was special in terms of its being a symbol of remembrance as well as anticipation; never did the word “present” feel so apt. Katzer has taken lines from Johann Peter Eckermann’s Conversations With Goethe and placed them directly within the piece. Delivered by the conductor to the audience, the lines relate specifically to the nature of new composition, and concern a new piece written by none other than Felix Mendelssohn. As recorded by Eckermann:

Conversation from Sunday evening, January 14 1827:

I found a musical evening entertainment with Goethe, which was granted to him by the Eberwein family together with some members of the orchestra. Among the few listeners were: General Superintendent Röhr, Hofrat Vogel and some ladies. Goethe had wished to hear the quartet of a famous young composer, which was first performed. The twelve-year-old Karl Eberwein played the grand piano to Goethe’s great satisfaction, and indeed excellently, so that the quartet passed in every respect well executed.

“It is strange,” said Goethe, “where the most highly enhanced technique and mechanics lead the newest composers; their works are no longer music, they go beyond the level of human feelings, and one can no longer infer such things from one’s own mind and heart. How do you feel? It all sticks in my ears.” I said that I am not better in this case. “But the Allegro,” Goethe continued, “had character. This eternal whirling and turning showed me the witch dances of the Blockberg, and I found a view, which I could suppose to the strange music.”

It’s interesting to note that Mendelssohn and Goethe enjoyed a great friendship thereafter.

Katzer noted in the program notes for a 2016 presentation with the Dresden Sinfonietta that his inclusion of Goethe within “Szene” should “not be interpreted as malice towards the genius. Lack of understanding of new music is a widespread phenomenon and, as we see, not a new one.” His essential point is clear, driven home by the work’s closing scene: the musicians gathered around a spinning top, silently observing. Our perception of change and its inevitable nature is coloured by a near-unconscious wiring of a past we don’t want to remember, yet cannot forget, much less look away from.

Katzer passed away earlier this year — on May 7th, to be precise, which is the date Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony made its world premiere, in 1824. The two composers shared a program last December thanks to the Rundfunk Sinfonieorchester Berlin, when Katzer’s “discorso” for orchestra was given its world premiere just prior to the orchestra’s annual New Year’s presentation of Beethoven’s famous symphony. I thought about this strange confluence experiencing “Szene”, and of Beethoven’s reported meeting with the very man Katzer quotes. The composer created incidental music for Goethe’s 1788 drama Egmont, as well as lieder incorporating his texts. The two came from utterly different worlds — Goethe being Privy Counsellor at the Weimar court, Beethoven, decidedly revolutionary — but despite such vastly different experiences and worldviews, the composer was effusive in his praise of the writer, and Goethe may have enjoyed the new sounds Beethoven created, however much he would complain about his sticky ears to Eckermann just four years later. According to an account in Romain Rolland’s famous book Goethe and Beethoven (1931):

On October 27th (1823) a Beethoven trio was played at Goethe’s house. On November 4th, in the great concert given at the Stadthaus in honour of Szymanowska, Beethoven figures twice on the program. The concert opened with the Fourth Symphony in B Flat, and after the interval his quintet, op. 16 for piano, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon, was played. Thus Beethoven had the lion’s share, and without mentioning his name, Goethe confessed to Knebel that he was again “completely carried away by the whirlwind of sounds (da bin ich nun wieder in den Strudel der Tone hineingerissen).” Thus there had been opened to him a new world, the world of modern music which he had hitherto refused to accept — “durch Vermittelung eines Wesens, das Geniisse, die man immer ahndet und immer entbehrt, zu verwirklichen geschaffen ist (through the medium of one who has the gift of endowing with life those delights which we resent and of which we deprive ourselves).”

Classical music lovers tend to enjoy —nay, expect —the so-called canon to never change, let alone the ways it’s presented (something Washington Post classical writer Anne Midgette addresses in a recent piece). However, contemporary composers have mostly embraced change and risk, frequently at the cost of widespread popularity and acceptance; they, and the artists who perform and program them, stand at the vanguard of creative evolution, come hell or highwater, fully present of time, place, space, and relationships. The ensemble unitedberlin was formed at the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989; like many German cultural institutions, it’s using 2019 to mark the changes wrought over three decades — how past merges with present, in sculpting possibilities for the future. As the program states, the group’s aim has been to explore “areas of tension, between the past and the future,” presenting works that incorporate and inspire a “joy of musical discovery.” Experiencing many works live that I’d not been given an opportunity to hear live before was not only a discovery, but a revelation; it’s been akin to squeezing out a tube of a color never seen before and then experimenting with its application on different surfaces. There are certain works I’m happy to take a (lengthy) break from, but contemporary works I heartily want to explore; I have ensemble unitedberlin, in part, to thank for stoking that long-suppressed curiosity.

Hans-Jürgen Wenzel (from ensemble unitedberlin program)

Hans Jürgen Wenzel is one of those composers whose work I hope to know better. Along with “Szene”, his intriguing “Eröffnungsmusik” (opening music, 1978) was performed as part of their birthday celebrations; the program charmingly describes the composer (who passed away in 2009) as the “the initiator of the formation of the ensemble.” Wenzel was dedicated to introducing young people to contemporary music, and many of his students went on to become composers in their own right. It was a perfect opening to the evening, and enjoyed a perfect follow-up: the world premiere of young composer Stefan Beyer’s “зaukalt und windig” (cold and windy). Katzer’s “Szene” was followed by Vinko Globokar’s “Les Soliloques décortiqués”, premiered in 2016 by Ensemble Musikfabrik. The France-born Globokar, whose creative process involves writing music based around stories he’s written first, told The Globe & Mail in 2011:

“I was part of a group of friends, an avant-garde that was based on risk. The idea, collectively, was to find something new. But even if you didn’t find this end result, it was still okay, because you were exploring ideas. That kind of collective thinking we did has disappeared.”

Based on cultural experiences over the past few years, I’m not so sure that spirit has entirely disappeared — it’s just become more of an effort to find and subsequently commit to. It was a decidedly stirring experience, to observe Katzer’s widow interacting with Globokar (elegant in a suit), the young Beyer, and ensemble co-founder Andreas Brautigam casually interacting post-concert — generations of past and present, all moving into the future, in their own ways and methods. Here’s to the unbound joys of new discoveries, sonic and otherwise; may we never deprive ourselves of them, but welcome them, with open arms, clear ears, and brave hearts.