The bonds formed and broken over the course of the past twenty-two months has led to reevaluations around relationships, and the kinds we want, and don’t want, in our lives. Complex equations relating to time and energy, volume and content, content and quality are being weighted against sheer exhaustion; many are just so tired and often feeling so much older than our years. If age is most accurately measured in moments than time, as Lord Byron implied, there are a good few of us in the arts who have been rendered ancient between March 2020 and now. That sense of aging has played a significant role in why and how relationships have shifted and changed. Sarah Miller’s “On Not Talking To Someone Anymore” (at her website) and Katharine Smyth’s “Why Making Friends In Midlife Is So Hard” (The Atlantic) are documents of people reaching a certain pandemic point and realizing things have irrevocably shifted, for good and bad. The corona era has made those positive/negative lines sharper, and blurrier, at once; has what’s been lost, especially in middle age – outside of the physical – may or may not be worth mourning.

That loss seems more pronounced in some spheres than in others; the high-wire act of balancing solitude and community, isolation and relating, very much powers cultural expression. Vanishing and being vanished on, the sorts of people we spend time with or move away from (literally and figuratively), the nature of our relating, alone and otherwise – these notions hold particular relevance in an age where community matters less and more, at once. Such presence is more fraught (again, literally and figuratively) than at any other point in recent memory. In her piece, Miller points out that the reasons behind silences can, at least sometimes (and if you ask), be reduced to the petty, the mundane, the cutting truth (or untruth) of seeing yourself and your behavioural choices through another’s eyes (whether you have vanished, or been vanished on), and of the painful divides when experiences, time, and nostalgia for the passing of both are mismatched to the onerous realities of the present. Smyth explores the strangeness of connecting in a strange place, inwardly and outwardly, in engaging in a practice one less considered than simply enjoyed, and the various nuances of experiential difference that adhere to the digital pursuance of such. The profound loss to which articles both allude has been magnified by the relentless ephemerality of digital platforms carrying the ironic title of “social”, outlets which encourage anything but phones-away, non-posting, simple, human relating. Social media platforms, as many know, play to pandemic times: avoid safely, connect comfortably. Observing endless streams of photos posted by high school/elementary school friends/exes/co-workers/colleagues/casual contacts, one tends to automatically engage in the algorithmically-calculated behavioural compunction toward comparison-making. It is a human urge which technology has become adept at identifying and exploiting. The urge toward comparison becomes all the more pronounced when some places have live performance, and some places don’t – where some places have full houses (and antecedent requirements for that to happen), and some places outright cancel events. Such contrasts have a sometimes acidic effect for those of us in the arts, who have lost work or are still looking, who are looking to bump up CVs and pay bills. Not being a part of regular crowds these last almost-two-years (and thus not working, for the most part) encourages an insularity whereby anything good that happens to someone else, and thusly advertised, is now suspect. Envy, most especially within the cultural realm, has been writ large; those who have are in such sharp contrast with those who have not. What should be unvarnished joys – a new job, a trip, an excursion, a concert, a conversation – are flashpoints for lack, reminders of non-abundance and ultimate separation.

So much of what gets shared now seems mundane, overwrought, calculated, or a strange combination therein. People have largely burrowed into the, to quote Jim Morrison, “woolly cotton brains” of the familiar, following or leading lessons online whilst baking bread, with dusty blinds, gritty floors, and rattling furnaces intact. Ah yes, we say, seeing such familiar elements of the quotidian to which we’ve been reduced, I recognize that, yes. The yeast/flour scarcity in early 2020 has morphed into current supply-chain issues; baking shortages led to furniture shortages, and now, apparently grocery shortages, the very place the money once spent on cultural excursions, now doth flow. The familiar has become a safe bubble to love and resent, a strange new counterpoint of the era. Rising economic uncertainty, coupled with financial realities, mean community, as a lived reality, grows more distant under the weight of such mundanities, only slightly flecked these days by random twinkling lights of diversion, originating from strings of lights, rows of candles, and more often than not, a panoply glowing screens that keep us apart, talking (typing, tapping) about the same mundane things we all watched or saw or tweeted. Opening up to 50% capacity in Bavaria is a big deal – to hell with the screens, hurrah!

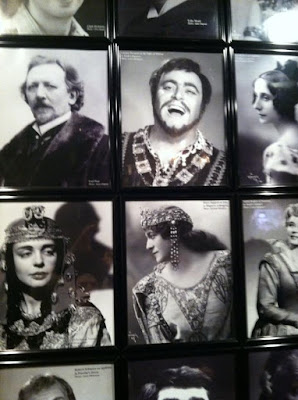

Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without express written permission.

But Mein Gott, who would go? Should I? Will I die going to see a concert or an opera? Or wanting to keep writing about such things? Will I get sick going backstage to interview, to chat, to greet, to hug and handshake? Drinks later? Oder? Was ist noch “normal”? Not being around people, or more importantly, being only around the same tightly-controlled group of people, aggravates such anxieties, leading to a reinforcement of experiential bubbles, and that is, obviously, bad for art, but it is what many are being forced to do, if not through their own choice now, than through guidelines that dictate external conditions. Thus do silence and its hurtful counterpart (vanishing) become as normal as overcrowding and cacophony, as alternating rhythms of zen and anxiety; somehow pandemic has underlined such extremes of living, and creating. I have come to understand, at a deep level, that people with families/partners/networks/busy jobs/illness are juggling heavier balls than I, a family-free freelancer. This isn’t to diminish the sharp and painful realities of solo creative life; lack of regular benefits, precipitous drops in income, whole months of work washed away, to say nothing of continuous days and weeks of isolation, makes those uniquely spiky freelancer balls difficult to keep aloft, and more than once I have dropped them all at once along with the concomitant connections meant to make them feeling lighter and less burdensome than they really are. Having needs isn’t the same as being needy, but often the two have blurred. Things which should connect – common interests, creativity, inspiration – somehow, now, do not. Conversation feels effortful, whether giving or receiving, and when it isn’t, one often feels as if there is a sense of impermanence: so if we have a grand old chat we can be silent for two months, right? We’d all cry out our grief, cry out our disappointment, to paraphrase Rumi, but we’re all too busy trying to survive, and besides who would want to make the effort to listen to such cacophony?

Trying to interact with those with whom we share such commonalities can be (often is, lately) like speaking the same language but with different dialects. Somehow Hugh MacLennan’s ‘two solitudes’ concept takes on a broader and yet more precise meaning; there is no real, shared language but for the words that indicate precise, sometimes intricate division, within the era of pandemic. Talking classical with equally-passionate others isn’t the doddle some may assume; it can rapidly devolve into ferocious spit-balling, name-calling, intransigent foot-stomping, bragging, finger-wagging, or some combination therein. It is not news that people who love the arts (and who work in the arts) hold strong opinions, but that’s where vanishing also (alas) can come in; such relating is exhausting, and everyone is, without question, already so tired, and thus such exchanges become another burdensome ball to keep aloft. The desire to engage in these tribalistic exchanges speaks to a need for (perceived) community, one which is greater than ever, one fostered by a love of culture, and more accurately, its live expression. New avenues can and are created within the heated (if hopefully well-ventilated) atmosphere of shared experience – but such communal engagement can paradoxically encourage a laziness of thought, a dampening of curiosity; there’s a fear of going against the herd indeed, but more than that, sometimes there is precisely no thought given to not fitting in with the herd, to not parrot what everyone says, to apply nuance, to apply context, to ask for clarification and to do so privately. There is an urge to simply agree and to “amplify” (that overused word of the times), an urge applauded and underlined by platforms which, as I’ve written, are ironically meant to encourage the notion of “social.”

Lately I have decided to keep most experiences (cultural and otherwise) to myself, to not share, to not opine, to not publicly offer applause or evaluation unless I feel it is truly warranted. I’d rather discuss these things privately with my small if trusted circle, not of necessarily “like minds” but of what I would call “like spirits.” There is more community found with such contacts, many of whom hail from entirely different cultures and backgrounds – we might have a shared love of x-y-z art, but that isn’t the reason we’re friends, and it isn’t the reason we might forgive (or question) each other’s occasional vanishings and silences – and frankly, we have the balls (I hope) to push back at one another as needed, if not always welcome. Kissing ass isn’t the point – sycophancy doth not a friendship make – because authenticity matters more. We like context; we like nuance. These things take time and attention, and when there’s time to be made, it is wholly taken. Chemistry can be cultivated, but it cannot be created whole.

Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without express written permission.

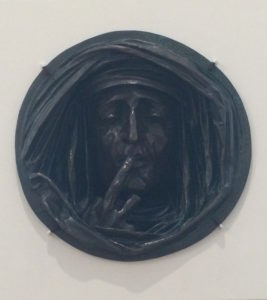

Accepting this has had personal ramifications. I have vanished on many; I have been vanished on by a great many more. I have become fussier in my interactions, and in the nature of those chosen interactions. This runs parallel with more selective listening and viewing habits; I am no longer a journalist or critic but my critical faculties now come with decidedly sharp edges, ones I wield carefully, according to that treasured context. In person, I have learned to speak with my eyes – and not. I have mastered obfuscation; I have learned silence; I thus can vanish, in many ways. Interacting from the literal and figurative safety of a monitor has given harsh if vital lessons. Rare is the moment I will drop any mask now, literally, or figuratively. The willingness to be vulnerable is what fuels meaningful connections, but its direct exercise is far more carefully considered these days. In his book La poétique de l’espace (The Poetics of Space) first published by Presses Universitaires de France in 1957, Gaston Bachelard devotes an entire chapter to shells and their paradoxical nature within the realms of creative human development. He ties artistic life with evolution of living forms, with “these snail-shells from which emerge quadrupeds, birds and human beings. To do away with what lies between is, of course, an ideal of speed… ”. In contemporary terms, that “doing away with” might constitute a great robbery, especially if one considers the heightened speed the digital world of 2022 demands, a pace which conflates perpetuation of connection with meaning, only to encourage its simultaneously illusory nature. Superficial ties are (mostly) easy to break; contacts we haven’t met (or barely met) are easy to vanish on. The people we meet and know are not immune to this virus of speed and ease, either, nor to the subsequent (and often casually done) breaking of those ties, ones which, within the creative realm, can be so inherently valuable. Bachelard continues, and offers a clue as to how to sort the vanishing/vanished-on fraught nature of modern adult relating:

A creature that hides and “withdraws into its shell” is preparing a “way out.” This is true of the entire scale of metaphors, from the resurrection of a man in his grave, to the sudden outburst of one who has long been silent. If we remain at the heart of the image under consideration, we have the impression that, by staying in the motionlessness of its shell, the creature is preparing temporal explosions, not to say whirlwinds, of being. The most dynamic escapes take place in cases of repressed being, and not in the flabby laziness of the lazy creature whose only desire is to go and be lazy elsewhere. If we experience the imaginary paradox of a vigorous mollusk – the engravings in question give us excellent depictions of them – we strain to the most decisive type of aggressiveness, which is postponed aggressiveness, aggressiveness that bides its time. Wolves in shells are crueler than stray ones.

Cruelty, it would seem, has been a hallmark of the pandemic era – cruelty, selfishness, pronounced exclusion and snobbery, bubble-think; they are behaviours that would seem to confirm beings comfortably, lazily ensconced within respective shells. For live culture and those who live by and for it, there should be another way, but we are all human, none of us (not even or especially artists) above any other with regards to the hurt humans are well capable of inflicting, and of feeling. And that capability to feel has not left, and indeed, should not.

But let us be wolves, then, in our shells, considering how best to spend and direct our energies and attentions. Energy goes where attention goes: let us hope we have learned how to direct it wisely. I want to feel such attention can be wielded, if not with great compassion (that seems like a big ask, and not a little precious), then at least with great curiosity, that such an exercise will get us out of our shells now and again, if only to breathe the cold, clean air.