As I poured hot water over my Bewleys tea bag this morning, I thought about the art of tea-making, and how much it’s changed, or at least been simplified and degraded by the busy nature of modern life. I enjoyed a thorough education in the fine art of tea and its enjoyment yesterday afternoon at the lovely In Pursuit of Tea, on Crosby Street in Manhattan.

Life has a way of turning out exactly like you didn’t plan. And yet it’s through the labyrinth of choice that we arrive at a new destination.

Life has a way of turning out exactly like you didn’t plan. And yet it’s through the labyrinth of choice that we arrive at a new destination.

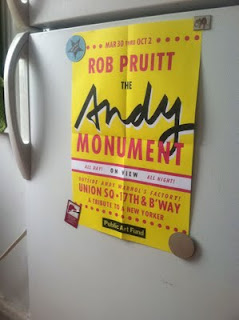

Maybe part of my inspiration is derived from the bright yellow poster for The Andy Monument hanging on my fridge. When I look at it I remember first catching sight of Rob Pruitt‘s gorgeous monument to Andy Warhol in Union Square just steps from where The Factory was once located. It was a mild, breezy day, and the public space heaved with Saturday shoppers and curious tourists who would approach the silver-chrome statue slowly, eyebrows scrunched and head cocked, camera-phone on the ready. Some people knew who it was, some didn’t, but most people were in awe of its sheen, its shine, its winking, blinking surface that glinted and glowed in the late afternoon sunshine. Some posed beside the monument; others clicked away, but it wasn’t a manic picture-taking frenzy like you’d see beside other statues of famous people.

There’s something curiously inspiring about this story. It got me thinking about the value we place on our activities, especially in the age of digital, where (especially as writers and artists) there is an expectation of “free” -a culture that has become a kind of monstrously growing pudding, one that keeps being fed by people who should know better. Whither worth? Everyone has to make a living -and has a right to. It can be, as Warhol serves to remind us, mundane, fantastical, or a mix of both (proudly), but we live in a culture where money is a vital form of energetic exchange. Those 15 minutes aren’t enough -you should either make money from it, or pay for it. Right? Wrong? It’s worth pondering, especially in an age where we choose to take and give things -talents, time, energy -without a thought. I wonder what Warhol would say.

There’s something curiously inspiring about this story. It got me thinking about the value we place on our activities, especially in the age of digital, where (especially as writers and artists) there is an expectation of “free” -a culture that has become a kind of monstrously growing pudding, one that keeps being fed by people who should know better. Whither worth? Everyone has to make a living -and has a right to. It can be, as Warhol serves to remind us, mundane, fantastical, or a mix of both (proudly), but we live in a culture where money is a vital form of energetic exchange. Those 15 minutes aren’t enough -you should either make money from it, or pay for it. Right? Wrong? It’s worth pondering, especially in an age where we choose to take and give things -talents, time, energy -without a thought. I wonder what Warhol would say.For a long time now I’ve wanted to write about my interview with Duane Baughman and Mark Siegel. The two men were in Toronto this time last year for the screening of their film, Bhutto, at the annual Hot Docs Film Festival, following their world premiere months earlier at the Sundance Film Festival. The Toronto screening came and went, life moved on, and I never seemed to properly make time to sit down and write – until now.

I discussed this in my chat with Duane and Mark last year on the radio:

There’s something deeply moving about seeing Gustav Klimt’s work in-person.

when one stands in front of these frankly very erotic drawings of young girls carried away by their own desire, eyes closed, lying on their backs with their legs wide apart and masturbating, they seem natural and are not at all embarrassing. …They are beautiful in their abandon, lascivious, but fragile and vulnerable, and one senses that the artist was touched by what he saw. There is nothing perverse or humiliating…

Hope as a concept, a feeling, a way of living and perceiving the world feels quaint, strange, and weirdly distant much of the time. And yet it’s what drives change in the world.

I thought about this after seeing Love Hate Love, a powerful documentary that had its world premiere at the tenth annual TriBeCa Film Festival lastnight. The work, directed by Don Hardy and Dana Nachman, seeks to counter society’s intrinsic pessimism with the idea of something bigger, larger, and more ultimately more important. The movie is a fantastic depiction of vision over visibility in action, viewed across three different lives and experiences. The TriBeCa Film Festival website wraps up the story nicely:

After Steve and Liz Alderman lost their 25-year-old son Peter in the World Trade Center, they took the money they were awarded as compensation and started a series of mental health clinics in Uganda, for those who have been victims of war crimes, child soldier enlistment, and more. After Esther Hyman lost her sister Miriam in the mass transit attacks in London on 7/7/05, she founded an eye care clinic in India in her sister’s name. And Australian Ben Tullipan lost his legs and suffered from massive burns in a bombing in Bali in 2002, after which he made a remarkable recovery.

In a world of cynicism, doubt, anger, vengeance, and fear, the idea of hope stands as a shy, if powerful presence that can change the entire center of gravity.

I didn’t know a thing about Win Win when I walked into the cinema to see it lastnight. I only knew it had award-winning actor Paul Giamatti as the lead, and it’s been popular with cinema-going New Yorkers who’s tried to get tickets, only to find screenings have sold out.

Lastnight wasn’t too crowded with people, but the film itself is chalk-full of ideas -and that corny old concept of heart. Except that in writer/director Thomas McCarthy‘s capable hands, it isn’t corny. He takes what could’ve easily been a very sentimental, schmaltzy concept and delivers with panache, subtlety, and a genuine human feeling for the characters and situations depicted.

The rain started in light spurts when I got off the subway Tuesday night. Fast-gathering clouds leaned down on an glassy towers and old concrete masses alike with bullying persistence. People glanced up nervously at the sky as they scurried along the sidewalks like nervous beetles. I’d just turned on Peter Gabriel’s beautiful cover of Elbow’s “Mirrorball” on my iPod and was wondering if anyone could hear the magnificent genius that was ringing, bell-like, in my ears. The track is taken from his gorgeously poetic album of covers, Scratch My Back, released in February through Virgin Music. The album contains a myriad of thoughtful, sometimes surprising cover versions, including Lou Reed’s sigh-worthy “The Power Of The Heart” (his proposal to now-wife Laurie Anderson), Paul Simon’s “Boy In The Bubble”, as well as David Bowie’s much-loved “Heroes”. The album is fast becoming a favorite on my iPod. It’s a million miles away from the noisy, posturing, abrasive world of modern pop. It’s not exactly get-up-and-boogie music, but rather, sit-down-and-shut-up music -and I like that. I wish more of that genre existed.

Far from being the bleeping, bloopy, busy electro-pop sound Gabriel became known for in the 1980s, Scratch My Back features minimalist production, a quality that immediately caught my attention. It’s very dramatic for its lack of instrumentation, and its careful consideration of orchestration in the way of what to put, and where. “Mirrorball” is a stand-out for its phenomenal string arrangements from Guy Garvey that, to quote Gabriel himself, “use all the colours of the orchestra to provide the heart, passion, intensity and groove” that lay dormant, if vibrantly alive, within the Elbow original. It does sound like Stravinsky -and Eno, and opera, prayer, incantation, invocation, moan and shudder, all at once. Upon first listen, walking through the ever-dampening, rapidly-darkening street in a New York borough, I wanted to weep, laugh, run, and stand still, all at once. Gabriel’s knowing, intimate delivery offers a beautiful, world-weary understanding of life and its variance. This begs for a video made in New York, complete with the huge, white flash of light and earth-shaking eruption of thunder that greeted its end the evening I listened to it.

Far from being the bleeping, bloopy, busy electro-pop sound Gabriel became known for in the 1980s, Scratch My Back features minimalist production, a quality that immediately caught my attention. It’s very dramatic for its lack of instrumentation, and its careful consideration of orchestration in the way of what to put, and where. “Mirrorball” is a stand-out for its phenomenal string arrangements from Guy Garvey that, to quote Gabriel himself, “use all the colours of the orchestra to provide the heart, passion, intensity and groove” that lay dormant, if vibrantly alive, within the Elbow original. It does sound like Stravinsky -and Eno, and opera, prayer, incantation, invocation, moan and shudder, all at once. Upon first listen, walking through the ever-dampening, rapidly-darkening street in a New York borough, I wanted to weep, laugh, run, and stand still, all at once. Gabriel’s knowing, intimate delivery offers a beautiful, world-weary understanding of life and its variance. This begs for a video made in New York, complete with the huge, white flash of light and earth-shaking eruption of thunder that greeted its end the evening I listened to it. It was beautiful in New York today.

It was beautiful in New York today.

The sun was shining, the sky was a lustrous blue, it was mild. The rain that had been threatened all weekend didn’t materialize. People were happy to welcome the spring weather, walking around in loose t-shirts and perhaps-too-soon rubber sandals. I got off work and decided I’d make a trip back to Strand Books. Poetry was calling, along with a general desire to walk around Manhattan on a gorgeous Monday afternoon and observe, reflect, walk, and breathe. The rhythm of street life -of peddlers, poets, con artists, lovers, dreamers, stragglers, strugglers, tired parents, scared tourists, oblivious locals, obnoxious students – all co-mingle here with a natural harmony that is both breathtaking and choking. Get out of the way!, I wanted to shout every few steps, if you want to yap with your boyfriend, don’t try to walk at the same time! Surely it’s a sign of becoming a local, though I still get shocked looks whenever I say “thank you” in a store. Habits from home die hard.