Today is the Super Bowl. Along with the inherent drama of watching grown men crash into each other as they engage in a kind of life-size version of a chess match and the fact that the New York Giants are involved (go Giants!), I’ll be watching because this year’s Halftime Show looks amazing. None other than Madonna herself is set to perform, along with LMFAO, Nicki Minaj and M.I.A.. Oh, and Cirque du Soleil are involved. If that isn’t entertainment with a capital “e,” I don’t know what is.

Hollywood awards season is a test of endurance for me. More of a clubby series of self-congratulatory pageants dressed in designer finery than a credible display of artistic achievement, the Oscars are perhaps the most obvious of high school popularity contests. And yet my stomach was all butterflies as I anxiously checked the list of Best Actor Oscar nominees this morning. There’s something about big-name recognition of longtime favorites that is immensely satisfying, popularity contest or not.

It was amazing – beyond amazing -to see Gary Oldman finally, at long last, get nominated for an Academy Award. Longtime friends will tell you I had a huge crush on him – or rather, on Oldman’s awesome, inspiring, occasionally terrifying talent. For all his talk of despising “the method,” he seemed to live what he acted. It was thrilling to watch him move between genres so easily, and become so unreservedly, uninhibitedly lost in a role. It still is, I’m discovering.

It’s hard to describe to someone who’s not been there. I’ve a friend who’s breaking her Big Apple cherry in March, and though the list of “you must go to”s keeps growing, I remind myself that every single person has a different experience. It’s like getting your very own personalized Ben & Jerry’s flavor: it has all the things you love, with little bits and bobs of everyone else’s yumyums, but you know it was made just for you, with a stamp in the middle when you open the lid saying START SPREADING THE NEWS. I found that flavor when I moved last year, and I had every argument with myself about why I didn’t deserve a flavor: I’m too stupid, I’m not connected, I’m too old, I’m not pretty, I’m scared. What? Gluttony’s in my veins. Gluttony shrieks for a metropolis that lives and breathes in a twenty-four hour cycle of survival, sweat, sex, sales, and rough-hewn savoir-faire. Gluttony has nothing to do with looks or connections or smarts. Gluttony doesn’t respect fear. To experience the full flavor, I only had to step outside and look around. It was so simple.

It’s hard to describe to someone who’s not been there. I’ve a friend who’s breaking her Big Apple cherry in March, and though the list of “you must go to”s keeps growing, I remind myself that every single person has a different experience. It’s like getting your very own personalized Ben & Jerry’s flavor: it has all the things you love, with little bits and bobs of everyone else’s yumyums, but you know it was made just for you, with a stamp in the middle when you open the lid saying START SPREADING THE NEWS. I found that flavor when I moved last year, and I had every argument with myself about why I didn’t deserve a flavor: I’m too stupid, I’m not connected, I’m too old, I’m not pretty, I’m scared. What? Gluttony’s in my veins. Gluttony shrieks for a metropolis that lives and breathes in a twenty-four hour cycle of survival, sweat, sex, sales, and rough-hewn savoir-faire. Gluttony has nothing to do with looks or connections or smarts. Gluttony doesn’t respect fear. To experience the full flavor, I only had to step outside and look around. It was so simple. Theorizing aside, home, for me, has f*ck all to do with where you’re born. Gabriel Byrne spoke about this very concept in May when he introduced Edna O’Brien at her reading for Saints and Sinners, his notion of Irish writerly creativity being tied up with what “home” means, of one neither comfortable in one’s adopted homeland, nor in the place one was born. I experienced that during a visit I made last month. It was bittersweet, surreal, and strange. I was home, but I no longer had an apartment. I had no base, but I was home, and I had everywhere to go. The sheer thrill of being there made me leap out of bed and thank some gritty unknown power. Living there inspired me to write page after page of ideas, observations, goals, experiences, and to get in touch with friends new and old. It scared the life out of me. It woke me up. I knew returning to Canada would kill me on some level, and it was a murder I had to accept as inevitable.

Theorizing aside, home, for me, has f*ck all to do with where you’re born. Gabriel Byrne spoke about this very concept in May when he introduced Edna O’Brien at her reading for Saints and Sinners, his notion of Irish writerly creativity being tied up with what “home” means, of one neither comfortable in one’s adopted homeland, nor in the place one was born. I experienced that during a visit I made last month. It was bittersweet, surreal, and strange. I was home, but I no longer had an apartment. I had no base, but I was home, and I had everywhere to go. The sheer thrill of being there made me leap out of bed and thank some gritty unknown power. Living there inspired me to write page after page of ideas, observations, goals, experiences, and to get in touch with friends new and old. It scared the life out of me. It woke me up. I knew returning to Canada would kill me on some level, and it was a murder I had to accept as inevitable. Photos from my Flickr photostream.

Inspiration has been hard to come by in these late November days. The greyness is thick, endless, unrelenting and unmoving, smug in its stifling tofu blandness. New tires spin aimlessly on a car that’s been flipped upside down and left to rot. Nothing goes forwards fast enough, if at all. To borrow from Beckett, “Nothing happens, nobody comes, nobody goes… it’s awful.” No kidding.

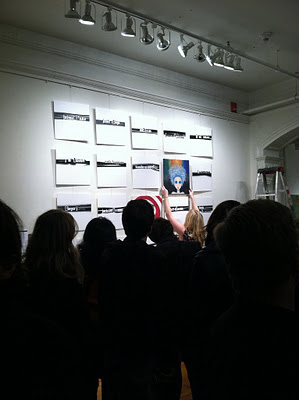

Showing the world my art was a strange experience.

Showing the world my art was a strange experience.

Many years and many canvases later, writing came calling again, as it inevitably would. Drawing came and went, as my visual side found expression in other things – a rediscovery of photography that ran parallel to technological advacenemtns in digital technology, experiments with black sharpies, trying out color conte for the first time. Drawing and painting had a surprisingly joyous union during a particularly experimental period last autumn, which, I have no doubt, planted the idea of my moving to New York City. Something about trying certain media together, at once, in totally new ways, blasted open neural pathways I hadn’t known existed.

Many years and many canvases later, writing came calling again, as it inevitably would. Drawing came and went, as my visual side found expression in other things – a rediscovery of photography that ran parallel to technological advacenemtns in digital technology, experiments with black sharpies, trying out color conte for the first time. Drawing and painting had a surprisingly joyous union during a particularly experimental period last autumn, which, I have no doubt, planted the idea of my moving to New York City. Something about trying certain media together, at once, in totally new ways, blasted open neural pathways I hadn’t known existed.

And that’s just how it felt, to look at my painting, hanging there with 24 other, entirely-other works. As Christopher observed, “Yours is so very different.” Of course my kid is different, I wanted to say. I didn’t plan it that way, but I’m not surprised that’s how s/he turned out. It’s nice to be with a crowd, but not of it. Even so, different-ness doesn’t guarantee confidence. Leaving my painting at the Gladstone was strange, and a bit stressful (it’s exhibited there with the others through Monday). I had a momentary twinge of -what, grief? separation anxiety? parental sentimentality? -when I walked into my tiny studio space at home and immediately noted that particular painting’s absence. It had become a sparky little fixture amongst the larger, older stalwarts, who seemed to hover and surround it in a protective huddle. I got cold thinking of it hanging in silence and darkness all night, alone and open to the elements of unfamiliar eyeballs and sneaky urban spiders.

A recent blog post on the organization A Work Of Heart was met with huge interest, and proved very popular across the internet. People applaud the marriage of creativity and commerce, because it doesn’t smack of the patronizing attitudes that so often dominate the conversation around aid.

Far too often there is a kind of smug arrogance over the role one may’ve played in some do-good initiative or another; one becomes more interested in our laser-pointed act of generosity to The Less Fortunate (who always, it must be said, remain nameless and faceless in their poverty) than in providing empowerment to achieve a livelihood not unlike our own. Western aid is often characterized by an agenda of righteousness, utterly lacking in awareness of history or culture. Self-empowerment, self-determination, responsibility and accountability… what’s that?

I don’t miss playing the piano. But I miss having a piano.

Watch Seamus Heaney Reads ‘Death of a Naturalist’ on PBS. See more from PBS NewsHour.

All the year the flax-dam festered in the heart

Of the townland; green and heavy headed

Flax had rotted there, weighted down by huge sods.

Daily it sweltered in the punishing sun.

Bubbles gargled delicately, bluebottles

Wove a strong gauze of sound around the smell.

There were dragon-flies, spotted butterflies,

But best of all was the warm thick slobber

Of frogspawn that grew like clotted water

In the shade of the banks. Here, every spring

I would fill jampots full of the jellied

Specks to range on the window-sills at home,

On shelves at school, and wait and watch until

The fattening dots burst into nimble-

Swimming tadpoles. Miss Walls would tell us how

The daddy frog was called a bullfrog

And how he croaked and how the mammy frog

Laid hundreds of little eggs and this was

Frogspawn. You could tell the weather by frogs too

For they were yellow in the sun and brown

In rain.

Then one hot day when fields were rank

With cowdung in the grass the angry frogs

Invaded the flax-dam; I ducked through hedges

To a coarse croaking that I had not heard

Before. The air was thick with a bass chorus.

Right down the dam gross-bellied frogs were cocked

On sods; their loose necks pulsed like snails. Some hopped:

The slap and plop were obscene threats. Some sat

Poised like mud grenades, their blunt heads farting.

I sickened, turned, and ran. The great slime kings

Were gathered there for vengeance and I knew

That if I dipped my hand the spawn would clutch it.

…when you’re beginning, you’re not sure. I mean, is this a poem? Or is it just a shot at a poem? Or is it kind of a dead thing? But when it comes alive in a way to feel that’s your own utterance, then I think you’re in business.

More often than not, it’s been poetry that’s brought me back to that uniquely personal “utterance” of late. Daily news does make a glorious, chaotic clang that is its own sexy siren song, but it doesn’t hold a candle to the more quiet meditations of poetry. That shrieking creative panic who troubles me morning, noon, and night seems like little more than an ignored muse who toes I keep inadvertently stepping on.

I’m always surprised and delighted by the sheer number of fascinating, artsy events happening in Toronto at any given time. In addition to Art Battle, A Work Of Heart, which also features live painting, is coming up soon. A Work Of Heart is an initiative that brings together artists and philanthropy in a spirit of cooperation, self-determination, curiosity and sharing. To quote its current release, “artwork is donated by seven local artists… half of the proceeds will go towards building a boarding school in Kenya’s Mathare Slum.”

Owing to conversations with TMS Ruge and other experts in the field of aid and development, I’ve developed a kind of mental alarm system for anything resembling Western-style feel-good-isms toward African nations. Too often those efforts are exercises in narcissism and brand-building, offering simplistic answers and reflecting the organizers’ romanticized (/stereotypical /racist) image of Africa and its citizens moreso than actively acknowledging the messy, complicated, multi-layered world of development and well, humanity overall. It’s easy to reduce a nation -its citizens within it, its continent around it -to easy slogans and poetic images, ones colored by celebrity visits and ad campaigns and big-ass concerts.

Casey: I also became extremely interested in aid and development issues while a student at Wilfrid Laurier. I have spent time volunteering in Morocco and Dominican Republic. Working and living with the local people in another country is a very different experience than simply visiting that location and its renowned tourist destinations. You get to really know the place, the people, their way of life and their motivations when you immerse yourself in their lifestyle.

The main thing I hear and read is that Western-style gestures don’t help in implementing long-term change – that it’s feel-good-ism for the privileged. How much of this initiative is about the long-term?

Laura: We work with an organization called Living Positive Kenya (LPK) which is located in the Mathare Slum, the second largest slum in Aftrica. This NGO is a support group for women and children living with HIV. Mary Wanderi, who founded this NGO (and is currently Director of Living Positive Ngong), is a pervious social worker who had the heart-breaking job of going into the homes of women who have died and retrieving their children. After dealing with an overwhelming amount of HIV related deaths she decided she had to take action. She then created LPK.

Why did you create A Work Of Heart?

Laura: I want to be there for the long haul. I am not looking for the the international ‘feel-good-ism’ experience and to simply walk away. These women aren’t just a group we support- they are our friends. We work together to figure out what the deeper problems are in the slum and try to find solutions that work for them and their community. After my first trip to Kenya, I felt that the amount of money needed to upgrade the LPK daycare was something I could easily fundraise. Selling my art seemed like the best bet to raise that money in my spare time. I paint as a hobby so it was nice to have a reason to do it more often.

What role do you see for art in helping to create social change?

Laura: Artists in general have a lot of passion and are always looking for ways to push boundaries with their talent. A Work of Heart allows them to push a new boundary because their art can now physically change a life for the better. Art is impossible to define but can be best described as something that makes us feel less alone. We want to take this concept and broaden it beyond the painting. Through the selling of our art we can connect to people across the world who are in grave need. It’s not just about painting a great picture; it’s about ‘painting a better world.’

Casey: Art is a positive practice that crosses language barriers and can be experienced globally. Art is exciting because it can mean something different to different people and create an emotional response. There is no right or wrong way to paint or be involved with art. I think that this project exemplifies how one person really can make a difference and that visual art, along with all types of art, like music, dance, can have a global reach and connect the world.

How do you find artists?

Laura: Networking. I have friends who paint who know other artists. It has slowly been growing over the past year. People I have never met want to donate pieces to me because they love the concept. It’s a great feeling to see how other artists connect to it so quickly and so passionately.

How do you hope to expand Work Of Heart and its reach?

Laura: We have decided to push our goals and limits further each year. Last year we aimed to raise $1,000.00 and this year we want to raise $10,000.00. This is our first art show. We hope to have larger ones down the road and have more artists from the GTA involved. We have a deep connection to the women and children we work with in Kenya and want to help them build a sustainable community for their children and themselves.

Casey: I hope to continue to raise positive awareness for A Work of Heart through the media and help to build a solid base of supporters. I am passionate about this project and happy to pitch something I truly believe in.

Faust is one of my favorite legends. The story of a man who defied the limits of mortality and the chains of morality has a resonance far past its German origins. I devoured both the Marlowe and Goethe tales as a child, enchanted by the mix of the dark and the divine. Years later, I discovered the operatic, musical, cinematic, and rock and roll adaptations. Faust reverberates a lot through popular culture, even making an appearance at the Crossroads, with one Robert Johnson. It brings up questions around how much you’re willing to trade in order to get what you want – not necessarily what you need, as the Rolling Stones astutely noted, but what your ego shrieks at you to go after, whether it’s love, money, fame, or a gilt-edged, flourescent combination of all three. “Careful what you wish for; you just might get it” -truer words were never more ironically bleated.

Director F.W. Murnau, best known for the creepy vampire flick Nosferatu, filmed a much-lauded version of Faust that was released in 1926. It would be his last German work before going off to Hollywood. Though we can’t surmise the sorts of sounds Murnau might’ve wanted for his classic work, we can at least use our imaginations, something that’s less and less common in the movie house these days. Accomplished Canadian composer Robert Bruce runs a series of live scoring events for silent films. He’ll be performing live musical accompaniment to Faust this coming Friday (tomorrow) night. We exchanged ideas about the film and the role of music in cinema.

Why Faust? What’s the attraction?

In this particular case, it is the film more than the legend for me. I have looked at many silent films in search of finding ones that still hold up well today, and ones that do well with my musical scores. I have to believe in the film quite a bit to even get started. Faust was a special case -the film is truly wonderful! What I have done with it musically is easily my best and most effective effort out of all the silent films I have scored. This sort of thing doesn’t happen too often in any multimedia project, where the planets just line up so well.

How did composing for Faust compare with other silent films you’ve scored?

More work went into composing special original music for Faust. The score is also longer than any other one (it’s just under two hours), and it’s one of the very rare silent film scores I’ve done that uses more of my deep, more (obviously) classical/ambient music, as opposed to the comedy programs which generally use lighter music. It is more involved -but also more rewarding, for me, and, seemingly, for the audience too.

Why do you think live scoring has become such a popular phenomenon in 21st century culture?

I’ve been lucky to have done extremely well with my silent film programs so far. Audiences have been very receptive and happy with my programs. Since I only work with select films, I’ve had the opportunity to really develop the scores and see that they blend and work well with the story/visuals. That’s something that probably didn’t happen too much back in the 1920s, as new films came in the theaters pretty much every week, and the house musicians had to keep up. It’s almost an advantage today to go back and revisit like this.