The lively Canadian violinist is currently on a tour that brings him to Toronto on Sunday, May 29th, where, along with pianist Andrew Armstrong, he’ll close the eclectic 21C Music Festival at Koerner Hall, a beautiful performance space attached to the Royal Conservatory of Music.

Lest you think any concert that takes place within the proximity of a conservatory is fusty, stilted, old-fashioned, or (shock!) outright boring, Ehnes’ concert will feature one Canadian debut, one Ontario debut, and one Toronto debut. All the composers for the respective works are living: Aaron Jay Kermis is a Pulitzer Prize winner who studied with (among others) John Adams and electronic music pioneer Morton Subotnick; Carmen Braden, based in Yellowknife, integrates the sounds of nature within her work; Bramwell Tovey is a Grammy and Juno Award-winning conductor and composer who was once described by Leonard Bernstein as a “hero.”

21C, launched in 2014, was created by Koerner Hall ‘s Executive Director of Performing Arts, Mervon Mehta, to, as he puts it, present “artists and composers I think have distinctive voices. […] I want to give audiences music, not medicine.” The danger with contemporary composition is, of course, that audiences might find it too cerebral, not melodic, odd, discomforting. The Ehnes concert, like so many others in the 21C program (including the kickoff concert, which featured Tanya Tagaq), mixes the old and the new with aplomb, and, in addition to the works of Kernis, Braden, and Tovey, will also feature the music of Beethoven and Handel, as well as a piece by James Newton Howard, perhaps best-known for composing the scores to The Hunger Games movies, along with numerous Hollywood hits. Oh, and it’ll be live-streamed. The online world is something many classical organizations are still coming to grips with, though some (and I’d include the Royal Conservatory here) recognize its potential and are doing very creative and unique (for the classical world) things in order to make the medium more friendly, and less daunting for newbies.

Making this world less daunting feels like an M.O. for many artists and arts administrators the last decade or so. Having interviewed Mehta prior to the start of last year’s 21C Festival, I wanted to speak with a performer at the tail-end of this year’s edition; since I’ve seen Ehnes perform many times (though I’ve never seen him perform contemporary work), I was curious to get his thoughts around the program, the role of modern music, why he uses Instgram (and makes it fun!), and what new audiences want and expect when it comes to classical music and culture.

(And for the record, yes, this new audio format is something I’m experimenting with; it may expand over the next few months. Stay tuned!)

|

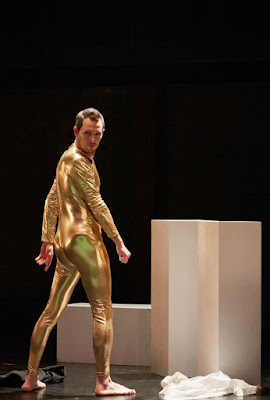

| Photo via Tapestry Opera |

What does “keeping the essence” of something really mean?

I recently attended a preview of Tapestry Opera‘s latest offering, an adaptation of DH Lawrence’s short story The Rocking Horse Winner, which opens in Toronto tomorrow night (May 28th). The tale, published in 1926, revolves around a boy who accurately predicts racehorse winners based on what he believes are tips from his rocking horse, in order to satisfy get the money to satisfy his upward-mobility-seeking mother. The company’s adaptation integrates contemporary elements with Lawrence’s original story, notably in its making Paul, the main character, autistic, and having the house he and Hester (his mother) share as being a real, actual character within Anna Chatterton‘s libretto and Gareth Williams‘ score.

During last week’s preview, Tapestry’s Artistic Director Michael Mori was asked, at one point, why such radical changes were necessary. Why alter something so dramatically from the original? What’s the point? Being curious about the art of adaptation, and passionate about opera as an art form, I thought it was worth asking both Michael and Anna for their thoughts — about the show, the adaptation, inspiration, and why and how change is a part of any adaptive process, especially for opera in the 21st century.

Why this particular story? Why did you think it would make a good opera?

Anna Chatterton (AC): D.H. Lawrence writes complex characters with a strong story structure. Composer Gareth Williams proposed the story to me, he particularly loved that the house whispers to Paul (the protagonist of the story) that was a clear singing opportunity. We could both see that the story could be distilled down and yet also expanded to tell a moving tale about greed, entitlement, and a complicated relationship between a mother and son.

Michael Mori (MM): He is one of the authors whose stories have stuck in my head ever since I was a child. And this story has great love, great loss, supernatural elements, and a house and horse that whisper and talk… so the space for music to animate the story is wonderful! Also, it is refreshing to have a break from romance and betrayal while still engaging in a subject with high dramatic stakes.

|

| Carla Huhtanen and Asitha Tennekoon. Photo by Dehlia Katz / Tapestry Opera |

AC: As it happens, that patron apologized to me afterwards, recognizing that we aren’t calling this opera “a dramatization of The Rocking Horse Winner” but “based” on The Rocking Horse Winner. (But) there’s a disconnect between everyone in the original story; so much is unsaid. We wanted to examine what was making the characters detach from one another — what barriers could be stopping them from understanding one another? From hugging one another? We’ve tried to keep this aspect of our adaptation present, yet also unsaid and under-the-surface. We wanted to explain yet still hang on to the otherliness of the boy at the heart of the story. There is a moodiness about the story, almost a nightmarish quality, which we followed; I would say in many ways the music is keeping the essence of the story intact. About a third of the original text is in the libretto.

MM: There are people who love period pieces being done in period costumes and re-constructed Victorian theatres – for example, Shakespeare at the Globe or La Traviata directed, designed, costumed, and set exactly as the score details. I am of the school of thinking that capturing the essence of the work involves interpreting it for a contemporary world. What Verdi, Shakespeare or D.H. Lawrence meant when they were speaking to the public of their generation and location would not be received the same today if performed or read exactly as it was. The essence of Rocking Horse Winner involves a plot structure, a specific dynamic between a mother and a misunderstood son, a class commentary in a period of time when entitlement is being challenged, and a loaded question of what is “luck” (which I take to mean, what is love)— all things explicitly included in the opera adaptation. Making Paul a young man on the autistic spectrum allows us to invoke a similar dynamic. Where the parenting role of an upper class mother in the early 20th century was being redefined in the time of the short story, the opera examines the role of an upper class single mother dealing with a developmentally challenged child, a situation and dynamic that, in 2016, we are continuing to learn how to better deal with.

Why have the house “talk” and not the horse?

AC: Because the house whispers to Paul in the original story, but the horse doesn’t. It didn’t even occur to us to have the horse talk…

MM: The house is the pressure, the question, the demand, the coaxing, and, therefore, the Mephistopheles to this family; a far more dynamic character and a more interesting expansion considering the potential of music.

Michael, your M’dea Undone last year was staged outside at the Brickworks, while Rocking Horse Winner is in a more traditional theatre setting. How do these locales influence and alter your decisions as a director?

MM: I would say rather that our shows influence our locales… When we see a place with the most potential for the work, we go forward. M’dea Undone has a truly expansive feel and, when we considered the scope of it, we fell in love with the idea of setting it in the Brickworks and accessing that urban, raw, and shabby-grand feeling that it invoked, so in keeping with John and Marjorie’s M’dea. Rocking Horse Winner is an intimate story, set mostly in a house… and the Berkeley Street Theatre became a wonderful place for us to bring a house to life, while inviting the audience inside.

What sorts of things within the score do you think are important to emphasize directorially?

MM: There are motifs that recur: the race, the mother, Paul… all appearing and reappearing in different ways. Since my direction is always driven by the music, I would rather say that clarity of drama in areas where the music is loud and raucous (where the words may be hard to understand) is one of the things that I strive for.

Why are works like these important for opera ecology in Canada?

MM: A simple answer would be that new works are important for the same reason that reproduction is important to any living ecology. Without reproduction, survival is endangered. If we allow the perception that opera is a museum form with an ossified and static repertoire, then growth and inspiration within the genre and its performance practice will be stymied. As we return to accepting new works (in new ways) into our understanding of opera, we not only engage new artists and audiences in a form that is more relevant to them, but we also are training a new generation of masters. Just think about Mozart or Verdi’s first two operas – they had to have had opportunities to grow towards their masterworks. This show in particular will be a valuable piece, as it proves that a beautiful musical aesthetic in opera doesn’t mean a derivative or overly programmatic composition.

|

| Photo by Darryl Block |

Attending and writing about opera on a regular basis, it becomes all too easy to take space for granted. The setting becomes almost secondary: the vast space of an auditorium, the plush nape of seats, the hushed, reverential silence during a performance. If you’re used to going to the opera, these are elements you don’t consider too deeply, if at all.

And yet, Against the Grain wants you to think, and feel, and reassess — and to approach opera in a whole new way. The Toronto-based independent company has built an acclaimed reputation on producing opera in unusual spaces; La Boheme took place in a bar, Don Giovanni was staged in an old theatre set up as a wedding reception, and now, Cosi fan tutte takes place in a television studio. Why should this matter? Well, for those of you who may never consider going to the opera, who find its formalities daunting, who feel it has “nothing for them,” AtG aims to make you re-think.

For opera fans like me, entering Studio 42 at the Canadian Broadcasting Company’s so-called “mothership” building in Toronto for A Little Too Cozy (AtG’s updated title for Mozart’s 1790 opera) was a strange if exhilarating experience — there’s a thrill of the new combined with a slight anxiety over gimmickry, and how much the old will be incorporated without being arch. While many directors approach operatic works with an attitude approaching holiness, some new productions are also occasionally done with an art-for-capital-A-art’s-sake approach. There’s still a widely held perception (one not completely incorrect) that curiosity, mischief and whimsy are missing in the opera world; Joel Ivany (who is AtG’s Artistic Director) keeps the proper reverence for the music (as he has in all his past works) but loses the poe-faced seriousness which opera neophytes might perceive comes with the territory, instead injecting a playfulness into the proceedings that is entirely fresh and creative.

|

| Photo by Darryl Block |

A Little Too Cozy is presented as a reality TV dating series, with each of the work’s characters as contestants vying to win love, and, it would seem, a measure of fame and validation. Felicity (soprano Shantelle Przybylo), Fernando (tenor Aaron Sheppard), Dora (mezzo soprano Rihab Chaieb) and Elmo (baritone Clarence Frazer) perform with phones in-hand, delivering punchy, swear-word-laden songs dressed in swishy club clobber, with sleazy Donald L. Fonzo (Cairan Ryan) hosting the proceedings and randy Despina handing the show’s talent relations. The latter two characters are, in the Mozart original, somewhat “controllers” of the situation, and the adaptation of them here, with more than a frisson of underlying sexual tension extant, makes perfect, zesty sense. What also makes this transposition work for the opera crowd is Ivany’s keen awareness of the source material being somewhat… silly, shall we say. In using a popular, mainstream medium to both mock and milk it at once, Ivany creates a foundation that is at once satisfying to opera regulars and enlivening to newbies.

After all, Cosi fan tutte (which translates roughly as “women are like that”) is not exactly what I’d call a work of great narrative genius; some of us (myself included) find the plot (which revolves around couples testing one another’s affections) rather unsatisfying, if not entirely asinine. But, by using a recognizable cultural outlet that has gained particular traction in the last decade-plus, Ivany betrays a deep awareness of both the power of media and the power of music, and marries them in a way that is entirely beguiling and extremely familiar. A Little Too Cozy is smart and fun and modern — it’s also very much opera. More fully than in past productions, Ivany and the AtG team here heartily embraced old and new, forging a sexy, sassy mix that will (and does) appeal to the social media set.

And so it was, the audience was reminded of related hashtags (#TeamDora, etc) and encouraged to use cell phones during the production. The immersive taping experience was deepened with “commercial” breaks, which allowed Ivany’s adapted libretto the opportunity to cleverly utilize and explore the re-imagined recitatives and arias (translated into English and matched to the proceedings) that provided further characterization and insight. It would be merely clever if it wasn’t also involving, entertaining, and deeply respectful to its source material.

|

| Photo by Darryl Block |

Perhaps AtG’s next project should be called, “So, You Think You Hate Opera” — I’d bet by the end of the night a few hearts and minds would be changed. Never mind the plush seats, here’s a beer and Twitter — sit back and enjoy. Opera can, and should be, for everyone.

| photo via my Instagram |

At this time last year, I was laid up on a sofa, tissues at the ready, sick with the flu. My mother had gone to a nearby friend’s for the New Year’s Eve countdown, with my assurance that was fine to leave me alone; I just needed rest and relaxation, and there was nothing further she could do past the jello-making and soup-heating and tea-freshening she’d been doing for twenty-four hours.

Wrapping herself in a thick, woolly, vintage Hudson’s Bay coat, a jaunty hat, and chunky knitted scarf, she sauntered down the snowy street around 8pm, returning just after midnight, eyes watering from the cold, but her face flushed with happiness.

“I had three glasses of wine!” she marveled.

It seems incredible, thinking back on that night, how physically strong she was, how capable I was, even with the flu, and how much 2015, as it rolled further and further along, took out of us both.

There’s a belief that hardships are sent to teach us something — about ourselves, about our attitudes; we endure them as a means of hardening our survival instincts and honing our notions of identity. It’s true, I’m grateful for the lessons each year has brought me, but no year has taught me more, on so many levels and in so many ways. No year has made me more cynical and yet more curious, more angry and yet more accepting, more honest and yet more aware of the drive to deceive and the great, frightening need some have to throw a theatrical, rosy cover across motive, intention, behaviour, and character. 2015: harsh, painful, important. I’m glad it’s over.

Realizing many of my local relationships aren’t as true as I thought has been a good thing, but it’s also been a painful lesson. I’m grateful to the good souls who call to check on me, who take time to visit or meet up despite poor weather and busy schedules, who don’t make excuses but make time. I’m equally grateful to the far-off people who send good wishes via social media, who follow my updates and share my work —they’re people who engage, interact, actively encourage and communicate; they take the initiative to stay in touch. They get it. Expressions of support and basic concern over the course of this horrendous year, many from quarters I hadn’t expected, were, and remain, very moving. It’s meaningful to know there are people out there listening and watching, who take the time and energy to stay in touch despite busy lives and schedules.

| photo via my Instagram |

Of course, nothing beats an in-person conversation. Taking the initiative to gently, lovingly pull me out of the cave of grief I frequently (and often unconsciously) retreat into is something I cherish, and to be perfectly frank, I wish it happened more often. In years past, I would always be the one planning, producing, pulling people together. I stopped doing that in 2015; illness and death left me too exhausted and grief-stricken. When the realization recently hit that the only holiday party I attended this year was the one I threw myself, I became both troubled and curious; should I work on being more popular? Should I find an outside job? Ought I to subscribe to the hegemony of coupledom? What about me needed to change? Then I realized, as I have so often throughout 2015, that some people — many people — are, in fact, self-involved assholes. There’s no getting around that harsh, if unfortunately true, fact.

Good moments from 2015 happened in direct relation with, or as a direct result of, my work. Teaching in the early part of this year was one of the best professional experiences of my life; being around students with an abundance of energy, curiosity, and so many incredible stories and passions was a life-enriching thing, and I am greatly looking forward to returning to it. Deeply satisfying writing and reporting opportunities blossomed with CBC, Hyperallergic, Opera News and Opera Canada magazines, as well as the Toronto Symphony. Likewise, many of the best conversations, connections, and concentrations happened in and around, or because of, music and art. Good people and great moments came into my life because of shared passions. Such happenings were like shooting stars: bright, magical, brief. That is, perhaps, all they were meant to be, but their memory is beautiful, a work of art, something I go to and stare at in mute wonder.

Wonder is what shimmers around my favorite cultural things from 2015. I generally dislike “Best of/Worst of” year-end lists — to use one of my mother’s old phrases, it’s no fun looking up a dead horse’s ass — but there are certain moments that stick out: the thick, heavy lines of Basquiat’s paintings, bass baritone Philip Addis’ expression as he leaned, Brando-like, against the set of Pyramus and Thisbe, Daphne Odjig’s bright, vital colors, the way soprano Kristin Szabo and bass-baritone Stephen Hegedus looked at each other in Death and Desire, Carrol Anne Curry’s laugh. I don’t want to get too trite and say “art saved my life this year,” but, in many ways, working in and around culture, sometimes through very harsh conditions and circumstances, was the best kind of therapy. My mother worked for as long as she could; it gave her a sense of accomplishment, pride in a job well and thoroughly done. Work for her was, I realize, a necessary distraction through the horrible illnesses she faced in her fifteen years of her cancer. More than a distraction, work was a kind of beacon of security, even when the nature of the work wasn’t entirely secure; the nature of the work, and the feeling it gave her, were. I get that.

| photo via my Instagram |

And so, as 2016 dawns, I’m tempted to want for more: more art, more magic, more satisfying work. But as 2015 so succinctly taught me, you can’t plan for pain; you can only ride its high waves, and hope, when you get sucked under, you don’t swallow too much salt water. I didn’t emerge from that sea a tinfoil mermaid; I emerged battered, bruised, with an injured foot and a sore heart. I don’t feel strong as 2015 comes to a close; I feel different. I’m more suspicious of peoples’ motives, less tolerant of bullshit. I love my work, and the possibilities it affords. There are places I want to travel, people I want to meet, things I want to see. I wish for more sincerity. Such a desire isn’t on a timetable, unfolding precisely over the course of one year, but I suspect that it helps to stay curious, critical, controlled in reactions and devoid of drama.

2016: less assholes, more authenticity. It’s a start.

There was once a time when Christmas was a very big deal in my life. Christmas Eve was a swirl of hot chocolate, cartoons, and peeks under the tree; the day itself was filled with a bevy of boxes, shiny ribbons, stockings filled to the brim.

Value comes in many forms, of course. Having dear friends coming over through the holidays this year, people close to both of mother and me, is a gift in and of itself. I thought it would be fitting (and fun) to look back at old times. Going through the many old photo albums stored in my basement has forced me to admit it something I’ve been avoiding the last month or so: the holidays hurt. I’ve been keeping myself busy with writing, baking, all manner of household thing, but the shock of my mother’s absence this year is sharp, unrelenting, brutal. Beyond going to the Royal York, and, more recently, my cooking up a beautiful Christmas dinner for us, we didn’t have many traditions. That doesn’t mean her presence in and around the house — as I baked, wrapped presents, drove her to friends’ for merry deliveries — isn’t sorely missed. She’d always laugh whenever I’d put on How the Grinch Stole Christmas and Merry Christmas, Charlie Brown.

Other memories of her at this festive time of year are dim, though I have some lovely photos to remind me of the wonder of childhood; a veritable smell of gingerbread and vanilla wafts off them, dreams of sugar plums and plush red dresses and the smooth threads of a Barbie’s hair. My world was cozy, cradling, perfect. Small snippets of that feeling came through in subsequent years; though I don’t have any photos from last year’s Christmas, I distinctly remember the absolute thrill I felt at seeing her take a second helping of turkey, exclaiming, “your chestnut stuffing is sooooo good!”

An overpowering love pervades everything; that is what I see and what I feel when I think of Christmases past. The tidal-wave-power of that love is one I’m not sure I’ll experience again; I chose not to have my own children a long time ago, and I am really not the maternal sort (something my mother also acknowledged), though I admit it’s been very joyful to see updates of others’ families on social media. “Christmas is for kids,” my mother dryly observed over the last few years. I couldn’t agree more. So it’s nice to experience the joy of the holidays vicariously, through the many hilarious/touching/smart updates I’ve seen on my Facebook feed; those photos and updates have brought many much-needed smiles and even laughter. To those who’ve provided such therapy: thank you.

|

| Heather Ogden in The Nutcracker. Photo by Bruce Zinger |

There’s always something special about seeing The Nutcracker every December. The story of two children who, joined by stable boy Peter, enter a magical Christmas land, is a perennial favorite, and a compulsory part of many ballet companies’ holiday programming. The work, first premiered in 1892, features a libretto adapted from German author E.T.A. Hoffmann’s story “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” and the National Ballet of Canada’s annual production, which features dancing bears, skittering chefs, and a sword-wielding King (of rodents, that is) — is a feast for the eyes and ears. James Kudelka, choreographer and librettist, has created a visual feast that captures the glittering beauty of a snowy Christmas but still retains all the warmth and merriment of the season, with the perfect mix of grand and intimate movements reflecting Tchaikovsky’s famous score.

This year marks its 20th anniversary, and opening night, the company featured its first Peter, Rex Harrington, along with his partner, Bob Hope, as Cannon Dolls (various “dolls” through the years have included Toronto Mayor John Tory, author Margaret Atwood, skater Kurt Browning, and astronaut Chris Hadfield). The show, which is an opulent riff on Russian design motifs (it even features a giant, decorated egg from which the Sugar Plum Fairy emerges), is a clever blend of old and new, European and North American, art and entertainment, and it’s these integrations that make it so successful. You know you’re seeing something artful and beautiful (Santo Loquasto’s set and costume designs are truly stunning), but at the same time, you can’t help but smile, even chuckle, at the panoply of delights being presented, whether it’s the dancing horse, skating bears (my personal favorite) or the giant Christmas tree, with its gracefully waving branches and bobbing baubles.

|

| Artists of the Ballet in The Nutcracker. Photo by Bruce Zingerr. |

It’s equally heartening to see students of all ages from the National Ballet School onstage, proudly strutting their stuff; such a buoyant presence gives one hope for not only the future of the art form, but for cultural presentation and passion. Ninety-eight students in total are featured in the production; they’re from the Ballet School as well as local Toronto schools. That’s an incredible achievement in and of itself —I imagine the backstage area of the Four Seasons Centre this time of year to be something akin to organized chaos— so full kudos are in order to National Ballet School Rehearsal Director Laural Toto and assistant Patrick Kastoff, as well as Stage Managers Jeff Morris and Lillane Stillwell, and Assistant Stage Manager Michael Lewandowski. Thumbs way up.

As with any proper professional production, none of the backstage chaos is, ever sensed onstage. The audience is left to wonder over the myriad of riches being presented, and, because of this richness, there’s always something new for us to consider and marvel over. This year I felt drawn to the team of young male dancers who have an especially impressive ensemble number near the beginning of the show. From my own vantage point, 2015 has been a year littered with numerous (and frequently painful) examples of machismo gone awry, so watching this year’s presentation of The Nutcracker, it was deeply refreshing to note the young male dancers and their smiles, their light-footedness, their utter lack of self-consciousness. This isn’t to say ballet can’t be macho — ballet history is littered with many dancers, male and female in fact, who have channelled a particular brand of raw power that has thrilled audiences over the decades — but there was something, for me, awfully touching about seeing young boys onstage, engaging in an art form frequently thought of as “girlie,” from of a purely joyous, non-gendered place. “I love doing this!” their bodies seemed to hum, “I love it!”

|

| McGee Maddox with Artists of the Ballet in The Nutcracker. Photo by Bruce Zingerr. |

Greatly complementing this pure instinct on opening night was dancer McGee Maddox, who, as Peter, radiated a cuddly, floppy-haired boyishness in his impressive turns, pas-de-deux routines, and great leaps of James Kudelka’s choreography. Less swagger and more sweetness, Maddox is a lovely, deeply likable stage presence, the perfect fit for a production that is candy-apple sweet and spicy-cider cozy. Joining him was Heather Ogden’s Sugar Plum Fairy (a gorgeously warm performance) and Robert Stephen’s Uncle Nikolai, whose great leaps and dizzying turns nicely integrated both commanding authority and playful whimsy. There’s something so special about walking out of a production feeling plain old good, and in this, the National Ballet’s production of The Nutcracker absolutely excels. Smiles are in short supply these days, on both epic and intimate levels; it’s nice to have a work that channels pure joy, unapologetically. We need it.

|

| Chris Mann as The Phantom and Katie Travis as Christine Daaé. Photo: Matthew Murphy |

Many of my regular readers will know I’m an opera fan. Through my formal reviews, features, and profiles, as well as my blog posts and tweets, I’ve not exactly made my opera passion a secret. I feel deeply blessed to have been able to so frequently combine my two loves — writing and opera — into a professional pursuit. I’ve always had mixed feelings toward musicals, however. Classic works like Guys and Dolls, Showboat, and Oklahoma! are forever favorites, while the more recent(ish) ones, like Les Miserables, Jersey Boys, and Miss Saigon, leave me with a vaguely discomforted feeling. Productions values in all of them are consistently exceptional, it’s true, but emotionally, much of their content leaves me utterly cold.

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s 1986 work The Phantom of the Opera, was, until recently, very much in the latter category, with the damning addendum that it was also unnecessarily mean-spirited to actual, real opera, something I still believe to be partially true. But the new production of Phantom (currently running at Toronto’s Princess of Wales Theatre as part of a North American tour) was a delightful surprise from my first viewings in the 1980s and 1990s. Based on the 1909-1910 serial novel (Le Fantôme de l’Opéra) by Gaston LeRoux, the musical follows strange and scary happenings at the Paris Opera House in the late 19th century; a ghost (the phantom of the title) haunts the theatre, living beneath the house and controlling what productions and performers will and won’t be on its stage. Ingenue dancer/singer Christine Daaé catches the phantom’s attention, and his fancy. Initially she is fascinated by him, and the connection he seems to have with her late musician-father, but she instead falls for childhood love Raoul, Vicomte de Chagny. When the Phantom’s real background, and then underground lair, are both revealed, tragedy ensues.

The dread-filled atmosphere and rich, velvet-vintage production stylings of The Phantom of the Opera conjure up Jean Cocteau’s beautiful 1946 film Beauty and the Beast and Tim Burton’s stream of goth-y outsider movies (notably Edward Scissorhands). There’s something about that aesthetic I enjoy immensely –the dark opulence of each feels comforting, cozy, a good place to hide. Lloyd Webber’s score is one I taught a seemingly endless stream of piano students two decades ago; now, I can honestly say thumbs up to the whole package. Though it has some creative production differences from the original (including a very cool revolving tower with plank-like, pop-out steps), the new production of The Phantom of the Opera has a fascinating and very involving atmosphere that is less owing to the mechanics (which are impressive, to be sure), and more to do with casting and chemistry. Gone is the pseudo-Grand-Guignol dread that hung over the original, and firmly in place is a sense of relationship between characters, and, notably, a greater, richer sense of the titular phantom. Chris Mann, a finalist on The Voice, infuses his portrayal with a sense of damaged, lovelorn isolation; the commanding, nasty character of old has been (wisely) replaced by a deeply lonely, desperate, rather pathetic figure. Any sense of terror is inextricably linked to (and catalyzed by) a sense of deep despair.

|

| Chris Mann as The Phantom and Katie Travis as Chris tine Daaé. Photo: Matthew Murphy |

When, in the final act, we see him surveying the underground world he’s known for so long, we don’t see a monster, but a damaged little boy begging for love; this is an important revelation, and it goes a long way to validating the kiss Christine plants square on the mouth before she departs. Truthfully, it was a kiss I used to flinch at — it seemed forced, corny, gross, especially considering how the Phantom had been less an “angel” to her than a domineering demon, shouting commands to “sing for me!” (here, that scene is presented as a formal voice lesson, with Mann gesturing across his chest and making wide motions with his arms, imploring her to “breathe”) — but that kiss is now one of acceptance and understanding, and it goes a long ways to unpacking the character’s psychology. In other words, it’s touching. Mann’s portrayal is less boorish, more boyish, and reveals the man, not the monster. The Phantom’s dangerous pranks — the slamming sandbags, the falling chandelier (which is, in this production, perched literally above the orchestra section of the audience), even the murdered stagehand who’d made fun of him — feel more like childish antics, more emo, less abomination. That may not be what traditional musical-theatre audiences want, but it’s what works for 21st century musical theatre. A more identifiable (and indeed, familiar) Phantom is one that hopes to attract a younger audience, one with higher expectations in terms of characterization, and specific cultural touchstones when it comes to portrayals of romantic, tormented outsiders.

In watching this new Phantom, one couldn’t help but be reminded of the moody anti-heroes from the Twilight series. The resemblances are, in many respects, striking, and it’s smart of producer Cameron Mackintosh to mainline this vibe for a whole new audience. His efforts are greatly enhanced with a young, dynamic cast, and Mann, along with Katie Travis (as Christine) and Storm Lineberger (as Raoul) turn in performances that give this Phantom a youthful vigor, one filled with intense emotions and operatic reactions that, while not matching the dread of the original source material, mines the story for its hormone-laden, tainted-love storyline, not to mention Andrew Lloyd Webber’s eminently hummable score. The sense of the work being mean-spirited to opera is still one I can’t quite shake (does the formal “opera” presented here have to be so utterly disjointed, snobbish, and generally discordant?) but soprano Jacquelynne Fontaine’s stellar performance, as the opera singer Carlotta, helps to elegantly quiet that notion. As with Mann, Fontaine’s portrayal is far richer than a cartoonish, one-dimensional, diva cliche. In performing the pseudo-opera “It Muto” (clearly a satire of Mozart’s works, particularly The Marriage of Figaro), Fontaine expertly balances annoyance, pathos, humor, ambition, and terror in equal measure, softening the harsh lines between “opera” and actual opera presented in the work, and succeeding, through her remarkable voice and stage presence, in bridging the two worlds with grace and a wink-nudge smile.

|

| Jacquelynne Fontaine as Carlotta Giudicelli. Photo: Matthew Murphy |

Still, one comes out of this new production of Phantom less smiling and more haunted at the impression it leaves; the portrait of a damaged, damaging loner with delusions of grandeur and the weak link in a wretched romantic triangle feels uncomfortably near. Never before have I emerged from a Lloyd Webber work hearing a melody in my head long after the curtain comes down, but the famous Phantom tune (a kind of unofficial theme) “Music of the Night” sat, ear-worm like, for several days, its Baroque-influenced lined and haunting orchestration seeping into consciousness along with Mann’s entreating expression. A Phantom for all times? I’m not so sure. A Phantom for the 21st century? Definitely. See it and decide for yourself.