Baritone Dominik Köninger / Photo: Tom Schweigert

So many things struck me the first time I saw Dominik Köninger perform live. Watching him, one senses an innate musicality combined with a natural confidence and stage presence. No wonder he’s a rising star in opera.

A native of Heidelberg, Dominik was a member of the International Opera Studios at Hamburg State Opera in 2007; from 2010-2011 he was a member of the Bavarian State Opera. In 2011 he won First Prize in the Wigmore Hall / Kohn Foundation International Song Competition and was also a Recipient of the Wigmore Hall / Independent Opera Voice Fellowship. He has performed at the Stuttgart State Opera, the Theater an der Wien, the Volksoper Wien (Vienna), the Deutsche Oper Berlin, and the New National Theater Tokyo, to name a few. In 2012, he became a member of the ensemble of the Komische Oper Berlin (or KOB; I’m a fan of their work), and has performed works by Offenbach, Gluck, Handel, Monteverdi, Rossini, Puccini, Mozart, as well as Oscar Straus. He’s also done extensive festival work, tours, recitals, orchestral appearances, and recordings. This season sees him in five KOB productions, as well as performances at the Opéra-Comique, Paris and a tour to Japan in the spring. “Hektisch” seems too mild a word to describe it all.

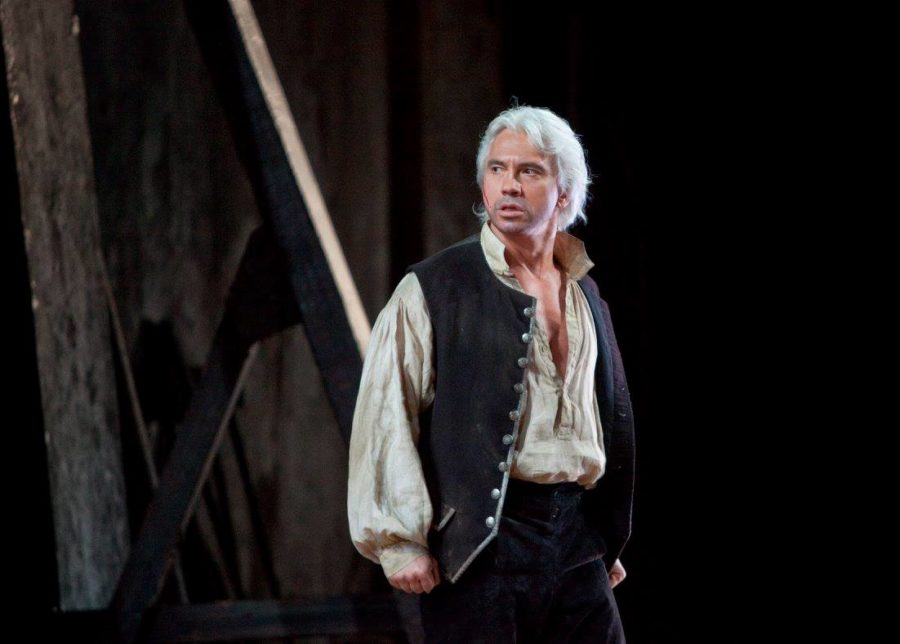

Dominik Köninger (Nero) and Alma Sadé (Poppea). Photo: Iko Freese / drama-berlin.de

We spoke this past spring just after I’d seen his riveting performance in Die krönung der Poppea (The Coronation of Poppea) as the corrupt Emperor Nero. Not only did composer Elena Kats-Chernin’s creative reworking complement the beauty and majesty of Monteverdi’s original (elements of folk, tango, and jazz were perfect), the performances, together with Kosky’s sexy direction, made it into something for the 21st century. Poppea‘s portrait of a rotting, decadent world was presented with every bit of panache, beauty, and flair one would expect from the company, but ugliness was not avoided. (The deaths of both Seneca and Octavia inspired audible gasps from the audience.) Nero, while written for a much higher voice type, perfectly suited Dominik’s baritone; he shaped the words beautifully, layered vowels with beautiful textures, modulating his coppery baritone to handle the score’s difficult runs and recitatives (recits) with complete confidence.

Dominik Köninger (Pelléas) and Nadja Mchantaf (Mélisande) / Photo: Monika Rittershaus

Debussy’s Pelléas is a perfect vocal fit, having been written for what’s known as a baryton-martin, a range that falls between the traditional tenor and baritone. Considerably more modern than Monteverdi but no less difficult (some argue it is one of the most challenging roles in the baritone repertoire), the 1902 opera, based on Belgian writer Maurice Maeterlinck’s play, revolves around a troubling love triangle and has been described by Sir Simon Rattle as “one of the saddest and most upsetting operas ever written.”

This Sunday (October 15th) Dominik makes his role debut as the ill-fated character in Pelléas et Mélisande, in a debut production for KOB (a co-production with Nationaltheater Mannheim), conducted by Jordan de Souza and directed by Barry Kosky, who recently noted that the psychological landscape of the work reminds him of Edgar Allen Poe. The production also features soprano Nadja Mchantaf as Mélisande and baritone Günter Papendell (whose Don Giovanni I so enjoyed this past spring) as the jealous Golaud. Along with Debussy, Dominik will also be performing at the end of this month with the Deutsches Kammerorchester Berlin at the Chamber Hall of the Philharmonie Berlin in a special Halloween-flavoured program that includes works by Schubert, Purcell, Grieg, and Saint-Saëns.

Photo: Jan Windzus Photography

A beautiful voice alone is enough for some, but blending the art forms integral to opera in a way that fits score and production, and connects with the audience, while casually carrying an innate, sparkling star presence — that’s the stuff I find truly exciting, and what makes me run to the opera house, over and over. As you’ll see, this is one direct singer; he likes to be challenged by new material but has no time for social media. (Don’t expect a Facebook page anytime soon.) He likes old work but has every curiosity for new stuff. He’s fine with the “barihunk” label but refuses the pressure that comes with technology. Dominik Köninger is, quite simply, his own man.

What’s it like to prepare for concerts versus opera?

That’s a good question. It depends on the role. A full recital is much more demanding than an opera. Let’s take Le nozze di Figaro: you’re on stage half of it or even less, and so it’s demanding of course, because you have to keep up the energy and all that. But to do a recital, I would say, the longer the better for preparation — a year at least. Sometimes it goes faster. You only have this one shot, this one-and-a-half hour block of time and you want to present everything you have in your mind, and the better you rehearse it, the better you can get it out there.

… and it’s just you. It’s just a series of solos.

All eyes just on you. All ears just on you.

Just people carefully listening.

That’s why I love it. You really can communicate much better with the people, you can look at them, smile at them — or not — and you can see how they react.

It’s a more intimate relationship with your audience.

Yes, and I really miss that, and I’m happy to be coming back to it.

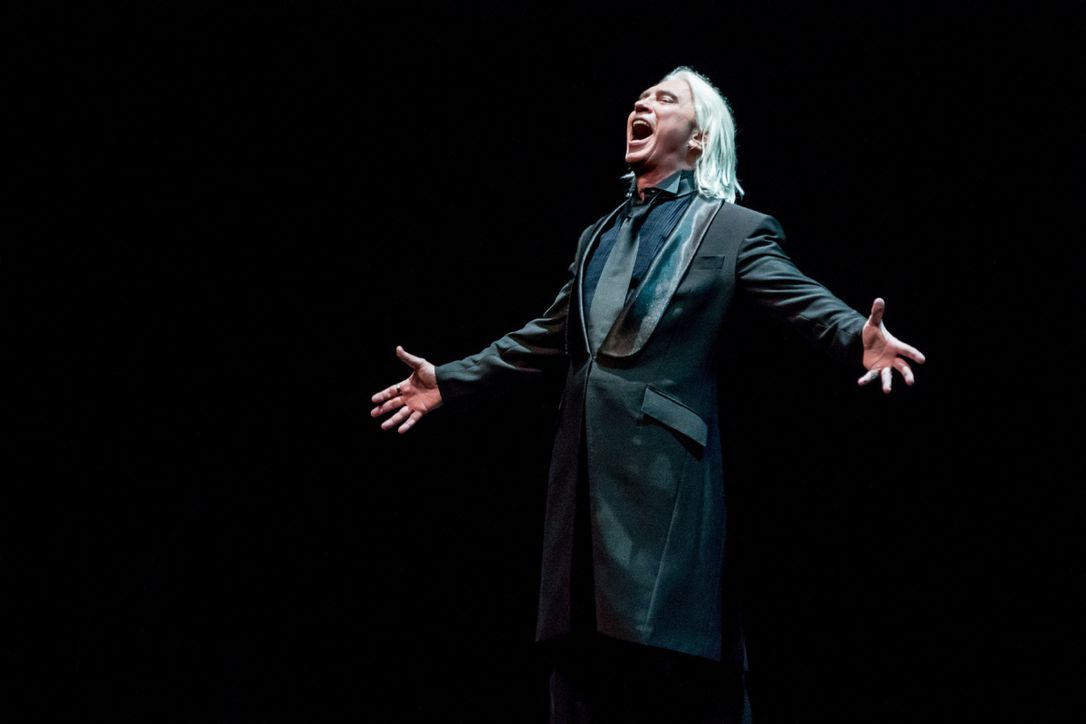

Günter Papendell (Golaud) and Dominik Köninger (Pelléas) / Photo: Monika Rittershaus

And you’re singing Pelléas as well.

This is my absolute dream role since I was 21.

What’s that like to prepare for something that’s been your dream for so long?

Difficult, to be honest. On the one hand I’m already familiar with it, because I sung parts of it in university but … on the other hand you have so many expectations of yourself, and this means pressure. So you have to release the pressure a little bit. It’s actually not so much a vocal issue, it’s more of a brain issue. I just need to stay relaxed. I’m really looking forward to it.

Is French opera something you enjoy?

I think it fits quite well to my type of voice. You know the lighter, higher-placed baritone, not the deep booming sound, that’s not me. French music is beautiful. I love it and I love the language. It’s my favorite language to sing in. I would love to sing Mercutio in Roméo et Juliette . This sounds cocky to say, but sometimes you discover that your soul —this means the combination of your soul and voice and all that — is predisposed to certain composers. Like, when I start a new Mahler song for example, I feel like I am already there. There’s still lots to improve of course, but it’s just… there, and it’s the same for Debussy songs and Fauré songs, it’s just there. That music goes into my voice so much quicker.

Dominik Köninger with Dagmar Manzel in “Die Perlen der Cleopatra” (The Pearls of Cleopatra) / Photo: Iko Freese / drama-berlin.de

Owing to live streaming and the Live in HD series, many singers feel they have to look perfect — what is that like to deal with?

That’s the reality today. That’s the thing. The better you look, the better you sing, the better you sell.

And you are on Barihunks.

This is really flattering, I have to say. I was and am always flattered when I read things about me. Those guys are ripped!

Keeping in shape is important for singers, though.

I feel better singing when I’m fitter, of course. I have great respect for older singers who can still produce all that sound and stay through a whole Tristan, or whatever they sing. I need to do just a little bit of sports to sing better.

What about after a performance?

I want to go home and watch “House of Cards”!

Do you ever see other productions?

When I was in Amsterdam this past spring, what I did was a bit crazy. I had a day off and nobody was there with me, so I enjoyed my time and went, on the first nice spring day — it was the end of March, really nice weather, at 2pm in the afternoon — I went to see Wozzeck at the opera. Really dark, really depressing, but good singers… great singers.

So many things are live-streamed these days. Does being filmed ever make you self-conscious?

If I started to think about all that onstage, I would be even more tense, so no. Somehow I manage to make myself free of it. I don’t think about how many people are watching and “Can they see into my mouth?” or whatever.

L-R: Günter Papendell (Golaud) Dominik Köninger (Pelléas), Nadja Mchantaf (Mélisande) / Photo: Monika Rittershaus

Is this why you’re not on social media?

I’m not interested. I have my family, I have my friends — there’s enough going on in my life. I’m always loyal to my friends, I write them on Whatsapp or message or call, but it’s enough. Sometimes people say to me, “If you were on Facebook, maybe your career would’ve been much better!” I’m like, “Or not!” It’s not my thing.

But being part of the Komische ensemble is pretty good, isn’t it?

This is how you see it, it’s how I see it, some people see it differently, and some need to sing in Vienna and LA and Moscow.

And you might do that anyway.

Yes, everything comes in its time.