Photo: Catherine Pisaroni

The last time I spoke with Luca Pisaroni, he was in Toronto with his beloved Lenny and Tristan, preparing to sing title role in Maometto II. The 1820 Rossini opera is a musically extravagant showcase of high-wire vocalism, demands which Pisaroni met with both cool panache and white-hot intensity. The Italian bass baritone has a knack for combining the hot and the cool; artistic passion is combined with technical meticulousness provide a genuinely authentic and very visceral live performance experience. What could be merely a cliched “Latin heat” is, with this artist, a genuine intensity of purpose, infused with palpable intelligence and grace. It’s one of the many reasons Pisaroni is so busy, and why he was recipient of a 2019 Opera News Award earlier this year.

Known for his stellar Mozart interpretations, Pisaroni is also ace with German and Italian repertoire, and has embraced the work of French composers in recent years. The Venezuela-born, Italy-raised bass baritone trained in Milan, Buenos Aires, and New York, and has worked with some of the world’s most celebrated companies, including Teatro Alla Scala, Opéra National de Paris, Bayerische Staatsoper, Wiener Staatsoper, the Salzburg Festival, the Rossini Festival, The Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, and the Sante Fe Opera. He is especially known (and rightly celebrated) for singing the work of Mozart, having appeared in La clemenza di Tito, Die Zauberflöte, Cosi fan tutte, and Don Giovanni. His Leporello in a 2016 Salzburg revival of the latter (directed by Sven-Eric Bechtolf) remains not only my favorite performance of that role, but one of my all-time favorite opera performances all around, authentically human and very theatrically satisfying. I’m not alone in this sentiment. In 2015, Opera News writer Fred Cohn wrote of Pisaroni’s Glyndebourne Festival performance as Leporello (in 2010) that it was one which “demands that you focus on the character, not the voice. This Leporello is both thoroughly likable — sometimes goofily funny — and morally ambiguous, a willing conspirator in his master’s cruel schemes. He is bound to Gerald Finley’s Don in a relationship that’s almost startlingly intimate but still immutably governed by the power inequity between master and servant. Pisaroni achieves this characterization with an integration of music and movement so complete that you’re hardly aware that he is singing — or acting, for that matter. You’re aware only of the dramatic moment.”

As Don Pizarro in Fidelio in Milan, 2018. Photo: Teatro Alla Scala/Brescia-Amisano

Pisaroni got the chance to be the Don himself earlier this year, in a Met opera revival. He’s also added roles to his regular repertoire, not Mozart works, but French ones (and one German) — both Berlioz’s and Gounod’s Mephistopheles, the villains of Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffman, Golaud in Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, Don Pizarro in Beethoven’s Fidelio. Tonight (26 April) Pisaroni adds a brand-new, never-before-seen role to the list, that of Lorenzo Da Ponte (librettist to Mozart, among other things) in The Phoenix, by composer Tarik O’Regan and librettist John Caird, at Houston Grand Opera. Pisaroni plays the younger version of the Italian-American writer/impresario/scholar, with baritone Thomas Hampson (Pisaroni’s real-life father-in-law) playing the elder Da Ponte. In addition to being partners in the new production, the pair are presenting No Tenors Allowed at Koerner Hall in Toronto on Tuesday (30 April), a program they’ve toured to great success, featuring a mix of classical works and show tunes. Later this year he’ll be touring as part of an in-concert version of Handel’s Agrippina in Luxembourg, Spain, and the UK, returning to Golaud at the Staatsoper Berlin and the villains of Hoffman at Wiener Staatsoper, doing an in-concert version of Don Pizarro in Fidelio (Montréal), and performing lots (lots) more Mozart (Figaro, Guglielmo, Leporello as well as his boss the Don) — in New York, Paris, Munich, and Zürich.

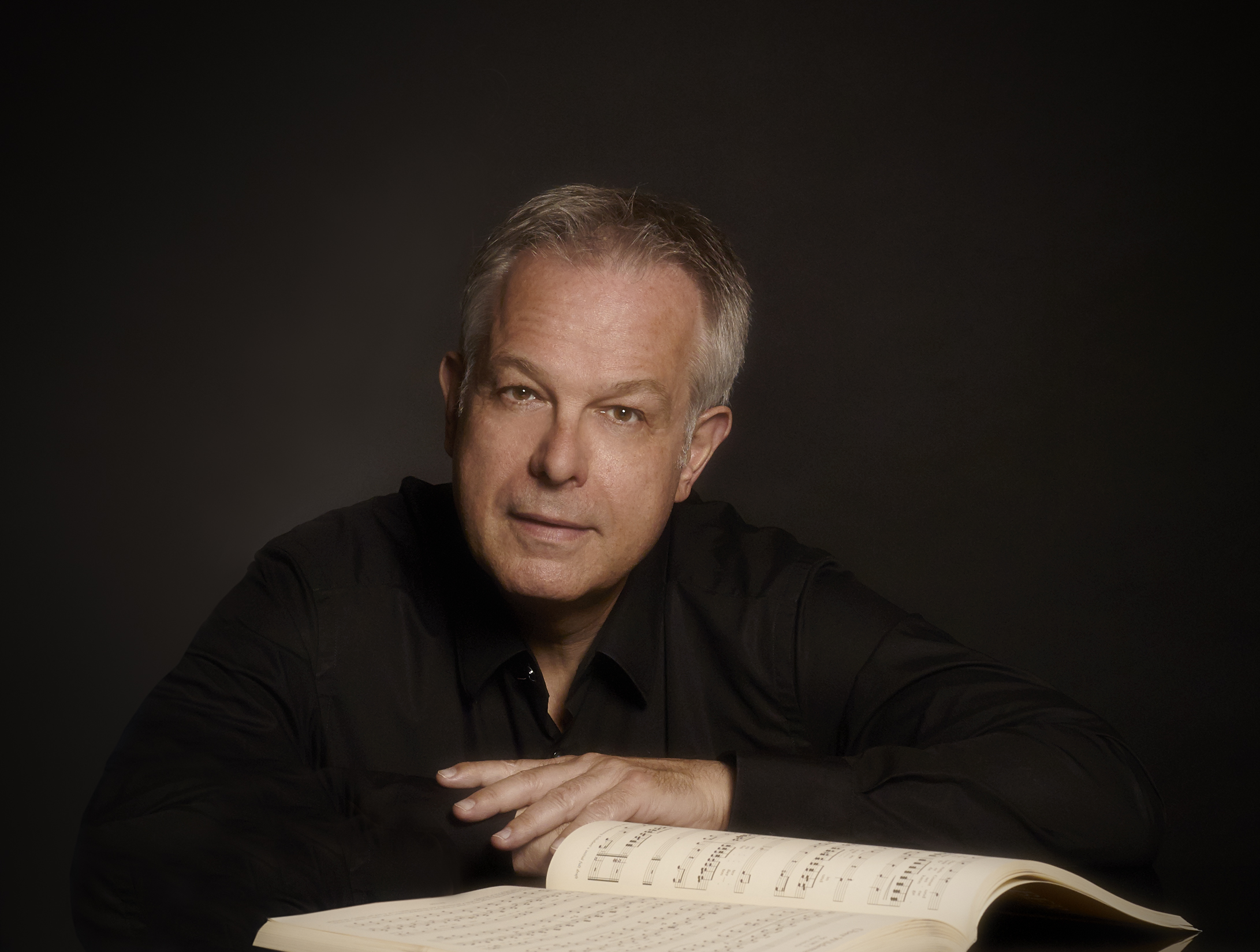

I spoke with both Pisaroni and Hampson separately; my interview with the baritone is here. What was so rewarding, coming away from each recent conversation, was the thoughtful nature of the respondents. Neither Hampson nor Pisaroni are interested in giving pat, tidy, soundbite-sized answers; they’re keen to explore various aspects of an ever-changing art form, the cultural/social/historical ideas that mingle with and transform old and new concepts of voice and theatre, and where, how, and why they fit into it all. It’s true, they are both low-voiced singers, they are family, they work together, their approaches are equally meticulous — but they’re rooted in entirely individual identities. Such uniqueness is what largely powers their real and ever-unfolding onstage chemistry. Each artist is so smart, so passionate, and very much an ambassador for their art form. Here Pisaroni muses on being an Italian singer doing a new work, vocal demands, his next (rather famous) role debut, why No Tenors Allowed is so special, and why it’s important to be more than a pretty voice.

With Thomas Hampson in The Phoenix, Houston Grand Opera, 2019. Photo: Lynn Lane

What’s it like to be part of a new project?

I would say it’s unusual for an Italian to do this. There is a tradition of people doing contemporary music but it’s like a niche; they just do that, they normally don’t do anything else. When Patrick (Summers) asked me if I was interested in playing Da Ponte, I said, “Hell yeah!” It’s such an interesting character, and he had such a fascinating life that I thought it would be really fun to play, and so here I am. The big difference is that Thomas has done quite a lot of new work and this is my first one — this is my first contemporary opera. I did a couple of modern pieces, like “Miserere” by Pärt (in 2016). It’s exciting to be able to create something that nobody has done, and have the chance to talk to the composer and be part of the process.

How do the vocal demands differ?

I try to sing it in the most natural way for me — it’s well written for the voice, but it’s definitely a challenge because it’s very rangey; it has a lot of high stuff and low stuff, high and lots of jumps, and so in that sense, yes, it’s a challenge. But I have to say it’s really well-written, and it doesn’t push my tessitura to an extent that it’s uncomfortable, so I just had to get used to it. In the beginning, the main issue was to learn the language of the composer, and that’s what takes a little bit of time — one needs to adjust. Eventually when you know it, you get it, and it’s really nice to be part of. Tarik (O’Regan)’s writing is amazing — there are some really unbelievably nice moments. At the first musical rehearsal, when we heard everybody else, the chorus and everything, we all went “WOW… “

As Lorenzo Da Ponte in The Phoenix, Houston Grand Opera, 2019. Photo: Lynn Lane

What do you think doing The Phoenix gives you as an artist? Do you come back to your more known repertoire with a different perspective?

That’s a good question. I don’t know! I’m going to do another world premiere in a couple of years, and I have to say, I actually enjoyed doing this; I’m surprised because I thought initially, “Well, I’ll try it once and see how it goes” — but it’s an interesting process, and it’s nice to be part of a creation. It gives you a good feeling. The most amazing thing is the fact the composer is there. I wish that every time I do something I could have the chance to talk to the composer and say, “What did you have in mind here”? But I think I will keep doing (new works), if they are offered it to me. It’s an exciting process.

Thomas said a project like The Phoenix feeds curiosity, a quality he feels is vital for artists.

That’s true. I always thought, the more you are exposed to new things, the better it is. For me (curiosity) is natural, though probably for some people, it isn’t. I have always tried varied things — songs, French and German repertoire — because I think it’s part of being a musician, to be curious, to try other things and explore the repertoire, to try as many styles and as many different types of repertoire as I can. I think it’s normal for a singer to try out things — and to remember that not everything you do is going to be successful; that’s absolutely normal, and it’s part of the game. Also, you may not like everything you do, but until you do it, you can’t judge. It’s like watching a bad movie and then saying you will not watch movies anymore; you watch ten, and nine are great but one is terrible. Are you never going to watch movies again?! This happens also with repertoire: until you sing it, you don’t know if it’s good, but you have to try. Only then can you say, “Okay it’s a role I won’t do again” but a priori, at the beginning, to say, “It’s not for me”, it’s not the right attitude for somebody who’s a singer / artist / musician who wants to try and evolve all the time.

Luca Pisaroni as Mephistopheles in Gounod’s Faust, Vienna, 2017. Photo: Michael Pöhn / Wiener Staatsoper

Part of your own artistic evolution has included French opera.

It’s amazing! This repertoire is just mind-blowing!

It takes a special attention and energy to do French music well; the things it often demands are things other repertoire doesn’t.

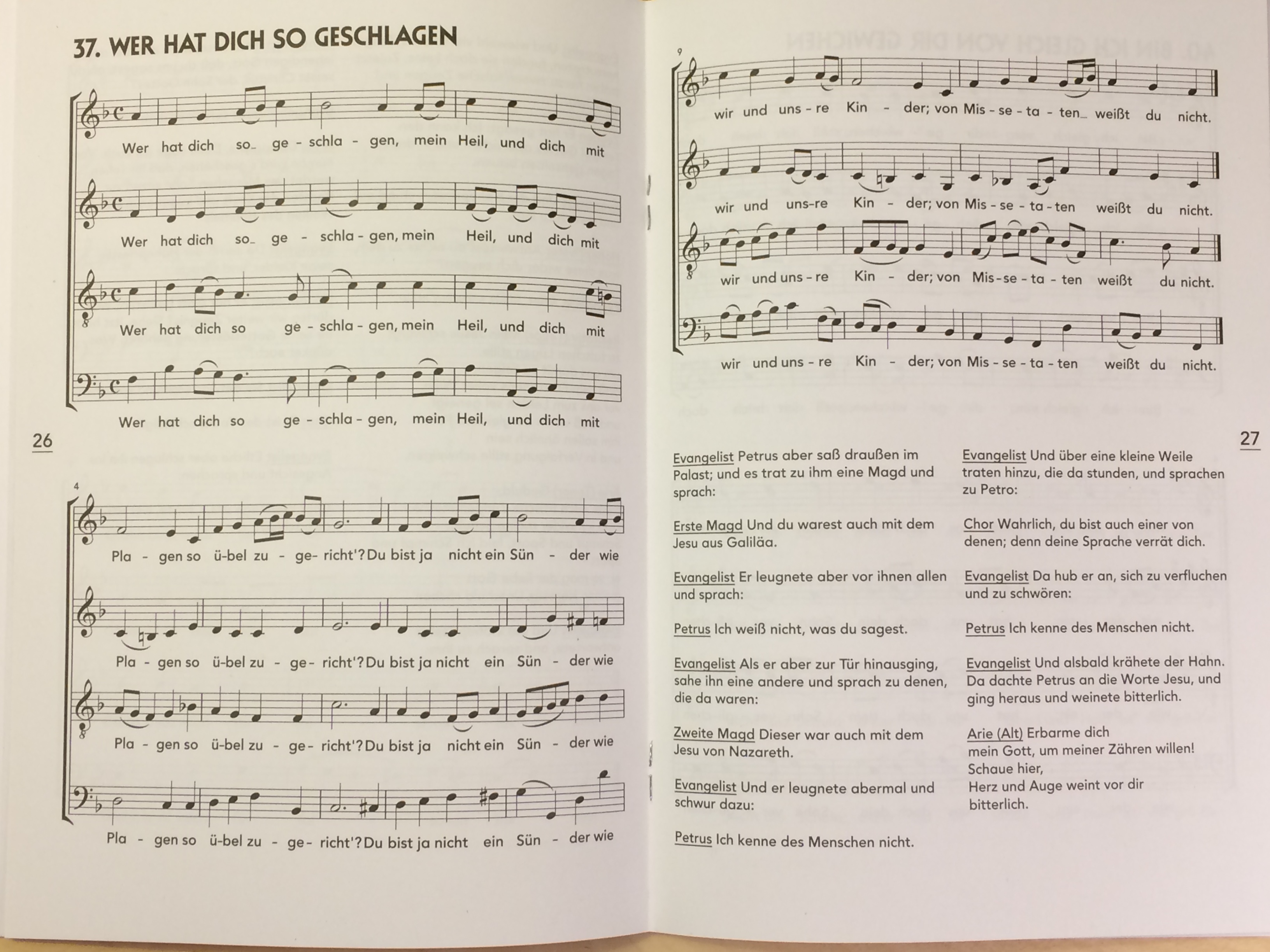

I agree. First of all you need to care about the language, and work on it. When it comes to Pelléas, it’s really the climax of French writing — it’s more like a play with notes than an opera. Music and words have absolutely the same importance; the combination is perfect. It does take a lot of work, but it’s a repertoire that I’ve found incredibly fascinating, and it’s written for my kind of voice, because it’s not really for a bass, it’s not really for a baritone, it’s right in-between, and I feel very comfortable with it. The tessitura is not constantly so high like it would be for a baritone. I’m happy I get the chance to do it, and I hope I get to do it all the time because I really really enjoy it.

But you’re also going to be doing your first Escamillo this summer, in Barrie Kosky’s production of Carmen at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. It’s an opera that tends to come with a lot of baggage, musically, historically, culturally, for a lot of people. What’s it like to step into? Some artists refuse to do it because of that baggage.

That’s why I haven’t done it earlier either — it has a lot of baggage, for sure, and there’s a lot of preconceived notions about the piece. I’m looking forward to seeing what I can do with it. The fact I haven’t done a production before, and I’ve never sung the role, will definitely help.

Thomas Hampson and Luca Pisaroni. Photo: Jiyang Chen

There may be some people who aren’t familiar with all of the music you and Thomas do in No Tenors Allowed — Mozart, bel canto, Verdi, show tunes. Why this kind of concert, now?

I remember when I was studying at the Conservatory, I bought the CD Thomas had recorded with Sam Ramey, ”No Tenors Allowed”. I think too often the repertoire between two male voices is kind of neglected, or not known as well as repertoire for soprano and tenor, but it’s so dramatically interesting, and it gives you a different perspective on the duet world in opera. To go from Puritani to Don Carlo and Don Pasquale and then to Broadway, I just think it’s interesting. We’re giving people a broad stroke of repertoire — we have fun doing it, and the audience have fun listening. It’s been a great project. Everywhere we go people say it’s fun to see us onstage, there’s such a connection. I’m happy to come back to Toronto for this. We’re singing one of my favorite duets, which is the Don Carlo duet — one of the best duets ever written. It’s just so powerful and so Verdi — so well-written and, dramatically, so intense. We try to give a dramatic sense to what we do, and to hear the reaction of an audience… it’s really gratifying. I do an Italian song also — after all, I am Italian! — and we do American stuff; I’m a huge fan of Cole Porter and Gershwin. It’s a really lovely evening and it’s very entertaining. There is such a range of emotion. There’s a little bit for everybody to enjoy.

As Caliban in The Enchanted Island, NYC, 2012. Photo: Metropolitan Opera / Ken Howard.

The drama within some of those duets reminds me of something you said a while back, that you weren’t interested in being known as a pretty-voice singer, but in being a singing actor.

When people come to an opera, they need to experience something that is not a voice lesson. Don’t get me wrong; the basis of being a great singer is that you should have a good voice and great technique. But our job as interpreters is to give somebody a dramatic experience and to tell stories and to make them go places within the opera they didn’t think they could go — and this is not just about singing pretty. I think a great voice without emotional connection is really… it works if we’re talking about Pavarotti; that voice was amazing, he didn’t have to act much because of that voice. But it’s one voice that exists in every 100 years. If you are not that kind of a voice, you need to tell a story. Even if I had the voice of Pavarotti, it would be the most important thing for me to tell a story, because without it, it’s not what we as performers are called to do. I just want to go onstage and tell somebody else stories; it’s not about me, it’s about the stories I’m telling. When I did The Enchanted Island at the Met, people didn’t even know it was me — I had to tell them. That was the best compliment I could have received.

There’s authenticity in that approach.

It requires, I don’t want to use the word “courage” because it’s not that, but it requires this desire to try, to risk. Sometimes it doesn’t work, because people might not get it, or your reading is not what people expect, but every time I’m onstage, I want to be somebody else, not me. It’s like when you play Don Giovanni, you don’t have to be a Don Giovanni in real life — but when you’re onstage, you have to think like him, act like him, and ask yourself: what would he do? You have to let yourself go and try to be somebody else. When I did Golaud onstage for the first time, a castmate said later, “My God, you looked really scary in that moment!” — I’d looked at him with such hatred — but it was the character. You have to push boundaries and try to tell the story. This has always been my target, and my desire. My idea of hell would be to do the same characters, the same roles, in the same way, every time. The great thing about this art form is that every night is different. You can have a fixed idea about the character, but you can also say, “Okay, I want to try something else”— that’s what makes this art form incredibly enjoyable, because every night you don’t quite know what’s going to happen.