|

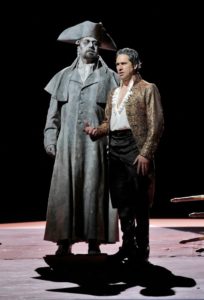

| Simon Schnorr as Don Giovanni in Jacopo Spirei’s 2016 production for Salzburger Landestheater. Photo: © Anna-Maria Löffelberger |

People come to opera with many opinions and ideas. If they’ve never seen a production, or have only caught tidbits online or the television, have gone at the behest of a significant other for a special occasion, or, they’ve worked in the industry their entire lives in some capacity, everyone has an opinion: It’s the greatest art form there is. It’s stagnant. It sucks.

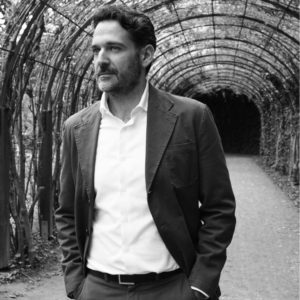

In speaking with director Jacopo Spirei recently, it seemed as if he was highly aware of all of these opinions, and moreover, had spent considerable time with groups who held a diversity of ideas around the art form. It’s this awareness, I suspect, that powers so much of his directing work; the Florence-based director has a powerful desire to reach through all the baggage a person carries (whether artist or audience member), to present something new and very immediate. Spirei, as I outlined in part 1 of our chat recently, spent the early part of his career working with British director Graham Vick, whose own stagings of operatic works have attracted their fair share of fans and critics. Vick is a figure who firmly believes in community involvement, and in reinforcing the art form as an intrinsic part of society.

Spirei has a similar approach. He has a number of acclaimed productions under his belt, including Rossini’s comic La cambiale di matrimonio (The Marriage Contract) for Theater an der Wien (Vienna) in 2012; another Rossini opera, the beloved La Cenerentola (Cinderella), for Festival Internacional de Musica (Cartagena) in 2014. He’s also worked with the renowned Co-Opera Co., helming productions of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly and Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) for the London-based organization. Spirei’s production of Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte won the audience prize for best production of the 2012/2013 season at the Salzburger Landestheatre, and he also helmed Gluck’s The Pilgrims of Mecca (La rencontre imprévue, ou Les pèlerins de la Mecque) there in 2013. Spirei’s resume is long and impressive, and extremely varied.

As he mentioned in part one of my interview with him, the busy director has been behind a few versions of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, including a popular, acclaimed version of the work staged at the Landestheater in 2011, and remounted in 2016. He’s set to direct Verdi’s Falstaff in Parma at the Festival Verdi in October.

With his recent San Francisco Opera debut, Spirei was tasked with re-envisoning Gabriele Lavia’s 2011 production of Don Giovanni. The director and I spoke just on the cusp of the production’s opening (on now through June 30th); thoughts about the dastardly deeds of the Don, as well as the centrality of women in Mozart’s famous 1787 opera, led to a broader discussion on opera attracting new audiences, the vital role of education, and the particulars of opera fashion. To go casual or not to go casual? Read on.

You recently told Newsweek that in Italy, opera is more about “pretty pictures”; I was reminded of the ongoing debate between new and old productions. Some people love the contemporary take on works; others feel there should be a return to beauty.

Yeah the problem is, what is beauty? It’s such a wide concept. When something you put onstage doesn’t help the story or doesn’t tell us anything, it hasn’t got a thing to say, then it has no place on our stages — it’s very simple. In a way you have to tell the story that is in the piece, that is written down; that’s where you start from. Of course you do it through your own intellect and creativity, but you cannot start decorating it; it doesn’t need that. The art form is absolutely fine on its own. What it needs is to be alive. It needs absolute essence, which is the live performance.

The joint work the director does with the conductor and the singers is to lift the opera from the page, to take it away from what’s written and recreate it, reinvent it. There’s no such a thing as pretty show or an ugly show; there’s a good show or a bad show. That doesn’t mean in-period not-in-period; somehow it’s a fake problem. If the work is good and relevant and done with honesty, then it’ll get through. Some work is provocative, some not, sometimes it want to be thought-provoking and hit something; each (production) has its own definition of beauty and of art, which makes us grow and develop.

… and some productions aim to be purposely unpleasant.

If you think about Caravaggio and a lot of his stuff, they’re beautiful paintings with incredibly morbid subjects: people without teeth, rotting away; fruit disintegrating. There’s a reason it’s rough, with that very harsh lighting. Beauty is, first of all, a completely subjective thing — I like purple maybe you like red, you see what I mean — in those terms it’s one thing. There are different styles, there’s brutalism, there’s a more decorative style. What I said about Italy and opera is not the fact that beauty is wrong, it’s just, instead of it being the obsession it used to be for this country — I mean, even Pasolini his own own version of beauty! — the theater has stopped developing, and become just a showcase of pretty costumes and nice scenery.

You mean museum pieces?

Right. So then you don’t need to do new productions — (old ones) were beautiful and had a lot of money (put toward them), a fantastic costume designer, what more do you need in life?

|

| Gillian Ramm, Laura Nicorescu & Tamara Gura in Cosi fan tutte from Spirei’s production for Salzburger Landestheater. Photo: © Christina Canaval |

The Met is grappling with this right now; the tension between those who enjoy what is called traditional stagings, and the group who say that’s boring and doesn’t move opera forwards.

First of all I think theater should be a leader, not a follower. The theater should lead an audience, teach an audience, make an audience grow, otherwise you end up with what TV has become, which is an endless number of reality shows, with no imagination, no creativity. In that sense the theater has to lead, in a way that works at every level; you have to show your audience a path and take them down that path. That’s one element of it, of course; the other element is the constant discussion about tradition. I find that very entertaining!

When we refer to “tradition” we’re basically referring to operas in the 1950s and 1960s. It’s a really narrow frame of time for almost 500 years of opera history. If you go and look at the operas written and performed in the 1920s and 1930s, the sets were different; if you look at some of the sets from the early music festivals, they did the most abstract, extreme productions that today would get completely trashed. We’re only referring to the system in the 1950s and 1960s, and little bit of the 1970s; what does it mean? Composers like Verdi cared so deeply about a piece, he would do anything to bring it to life. This debate on tradition, it means nothing!

What it is, is, it’s comfortable — and comfort is laziness. The comfort of it, it’s everything. Nowadays we live in a political world that is only looking backwards, thinking back at the supposed good old times, because we think we know what good old times were — but we never had good old times. Like, “oh remember the 1980s!”

|

| Ines Reinhardt and Sergey Romanovsky in Spirei’s 2013 production of Gluck’s The Pilgrims of Mecca for Salzburger Landestheater. Photo: © Christina Canaval |

People romanticizing the past…

Yes! So we have to move forward; we have no choice. As human beings, there’s no going back.

Where does art and accessibility to newcomers, fit in? A lot of people have said to me that they find opera intimidating, they don’t know where to start, they think they won’t understand.

You’re absolutely right when you say “intimidated” — we just need to take the aura off it. It’s not a church, it doesn’t matter what you wear so long as you come and watch it. The San Francisco Opera is doing this thing where they’re showing the opera at the baseball stadium. It’s fantastic! I’ve been taking Uber cars around, the drivers all ask me where you from what you do, and when I tell them, they say, “Oh how cool, I’m curious!” And I say, listen if you want to see it, go to the baseball stadium, on thirtieth of June, you can see it, and they all say, this is great, cool!

|

| The opening of the 2013-2014 Met Opera season; Eugene Onegin (with Anna Netrebko), broadcast live in Times Square. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission. |

It’s like the Met broadcasting its opening night in Times Square — I’ve gone to that more than once, and it’s fun. People bring thermoses and sandwiches.

Wonderful! Really, there’s nothing wrong with the art form, it’s fine, it just needs to be taken to the people. Of course, if the people don’t come to the theater, the theater has to go to the people, and find a way to go to the people, maybe not via the big institutions — you need the big institutions to keep the art form alive — but you also need the new world of young companies to bring the artform to the people and even take the people into the theater, or not, at least then it’s an educated choice. People can then reasonably say, “I’ve seen it and I don’t like it” or “Wow, that’s great!”

At least plant the idea…

Yes.

My attitude is, if you do want to come with me to the opera house, please make an effort to look smart; I like doing something special, and it’s nice to see people having the desire to do that. That doesn’t mean opera is snotty or elitist —dressing up doesn’t mean those things. I feel like we have to demystify the opera house as an overall experience, and that extends to fashion.

Absolutely. If a person says, “I’m not wearing a suit but I’m still going,” in a way, from my point of view, that’s the priority (getting them in). It’s like going out on a Saturday night: you dress up, but it shouldn’t feel like, “OH MY GOD I HAVE TO PUT ON MY BEST TUX!”

|

| Simon Schnorr und Sergey Romanovskys in Spirei’s 2013 production of Cosi fan tutti for Salzburger Landestheatre. Photo: Photo: © Christina Canaval |

But seeing jeans and sneakers sometimes frustrates me; I feel like we’ve coddled everybody, especially in North America, to constantly feel the need for comfort, throughout every single experience. It seems as you say, lazy. You can look smart casual, but that’s not the same thing.

Ah, sneakers and jeans, you see them everywhere. You can spend more on jeans than an actual tuxedo, D&G and Cavalli make some very fancy jeans! Times change, and all that develops, it’s absolutely fine, and again, one can like it or not like it. You have all the right to say, “If you come with me, look decent” — I don’t have a problem. What I think is crucial is to bring opera to the people, as well as people to the opera.

Nowadays, unless you live in Germany or Austria or a few other countries, you don’t grow up with music, it’s not taught in schools, the opera house is not a place where you go. I worked a lot in Germany and Austria, and it’s completely part of the culture. You take your kids to it, they grow up watching music and go to the opera and they are completely unfazed by it. They are not shocked, they have a relationship to culture; they know what they’re talking about when they discuss it.

It’s woven into the fabric of society there.

Yes, moreso than in Italy. I’ve worked so little in Italy; life has brought me outside. There’s a lot one has to say “no” to; it also has to do with the funding, (Italian companies) can’t really plan ahead because they don’t know if they will have money next year or how much money they might have. Italy has been cutting things regularly, every year, sometimes mid-season. So theaters are trying. It’s harder for sure — but Italy has also mismanaged money for a really long time.

And now it’s catching up with them?

Of course.

|

| Hannah Bradbury, Raimundas Juzuits, Florian Plock, Kristofer Lundin und Lavinia Bini in Spirei’s 2016 production of Don Giovanni for Salzburger Landestheater. Photo: © Anna-Maria Löffelberger |

It’s always the arts that gets cut first…

Always, and it’s the biggest mistake a society can make.

Education and arts are essential; theater is essential; if you study it, if you go, if you do it, you learn to be in somebody else’s clothes, somebody else’s problems, you start to empathize with those problems and become more tolerant and less judgemental, you are a better person. And being an audience in a theater makes you a better person also. It teaches you to be in a room packed with other people, and to really listen to something, not interfering with it or with others, but sharing an experience.