Andreas Schlüter, Kopf einer Göttin (Head of a Goddess); Bode Museum Berlin, 1704. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

A new year is a good time for assessments and remembrances, for reflecting on moments good, bad, and otherwise. As well as a desire to keep more cultural experiences within the personal realm, I’d prefer look ahead, to things that spark my imagination and inspire expansion, challenge, and evolution.

Earlier this year a friend observed that my tastes have become (his words) “more adventurous” over the past eighteen months or so. Flattering as this is, it’s also a reminder of the extent to which I have layered over my past, one largely spent wandering through the vast, lusciously dark forests of curiosity and wonder. Decades of weighty responsibility cut that forest down and gave me a deep trunk, into which all the unfinished canvases of a fragrant, lush wonder were stored; I came to believe, somehow, such a trunk had no place in the busy crowded living room I’d been busily filling with the safe, acceptable predictability of other peoples’ stuff. My mother’s passing in 2015 initially created a worship of ornate things from her trunk — perhaps my attempt to raise her with a chorus of sounds, as if I was Orpheus, an instinct based more in the exercise of sentiment than in the embrace and extension of soul.

Contending with a tremendous purge of items from the near and distant past has created a personal distaste for the insistent grasping and romanticizing of history (though I do allow myself to enjoy some of its recorded splendor, and its visual arts, as the photos on this feature attest). Such romanticizing utterly defines various segments of the opera world, resulting in various factions marking themselves gatekeepers of a supposedly fabled legacy which, by its nature, is meant to shape-shift, twist, curl, open, and change. It’s fun to swim in the warm, frothy seas of nostalgia every now and again, but mistaking those waves for (or much less preferring them to) the clear, sharp coldness of fresh water seems a bit absurd to me. À chacun son goût, perhaps.

František Kupka, Plans par couleurs, grand nu; 1909-1910, on loan to Grande Palais Paris; permanent collection, Guggenheim NYC. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Rediscovering the contents of my own trunk, pulling each item out, examining it in the sunlight, looking at what it means now (if anything) and deciding whether to keep or bin, has been a slow if meaningful process; it has been a homecoming to myself, one groaning and gloriously stretching with every breath. Refreshingly, such a process has not been defined by the rather narrow tastes of a somewhat culturally dictatorial mother, but by things I like, things I miss, things have no need to feel validated for liking.

“You’re so serious,” I was once told, “serious and critical and intellectual.”

I don’t know if any of these things are (or were) true, but making a point of experiencing the work of artists who reveal and inspire (and challenge and move) has become the single-biggest motivating factor in my life. “Adventurous” is less a new fascinator than an old (and beloved) hat. Here’s to taking it out of the trunk, and wearing it often and well in 2019.

Verdi, Messa da Requiem; Staatsoper Hamburg, January

The year opens with an old chestnut, reimagined by director Calixto Bieito into a new, bright bud. Bieito’s productions are always theatrical, divisive and deeply thought-provoking. Doing a formal staging Verdi’s famous requiem, instead of presenting it in traditional concert (/ park-and-bark) mode, feels like something of a coup. Paolo Arrivabeni conducts this production, which premiered in Hamburg last year, which features a stellar cast, including the sonorous bass of Gabor Bretz.

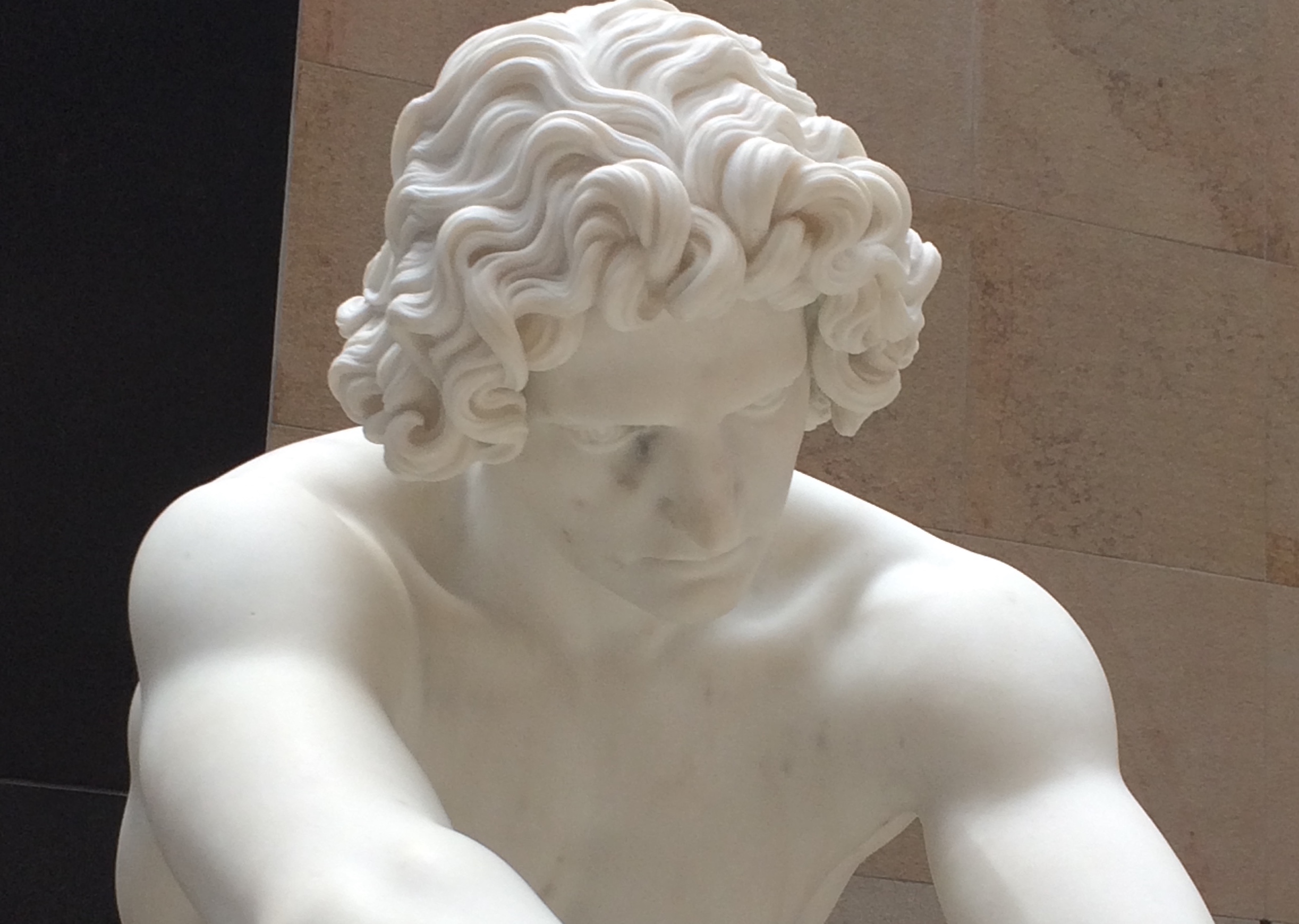

Jean-Joseph Perraud, Le Désespoir; 1869, Paris; Musée d’Orsay. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Tchaikovsky/Bartok, Iolanta / Bluebeard’s Castle, NYC, January

A double-bill exploring the various (and frequently darker) facets of human relating, this Marius Treliński production (from the 2014-2015 season) features soprano Sonya Yoncheva and tenor Matthew Polenzani in Tchaikovsky’s one-act work; baritone Gerald Finley and soprano Angela Denoke perform in Bartók’s dark tale of black secrets, last staged at the Met in early 2015. The orchestra could well be considered a third character in the work, so rich is it in coloration and textures. No small feat to sing either, as music writer Andrew McGregor has noted that “the music is so closely tied to the rhythms and colours of the Hungarian language.” Henrik Nánási, former music director at Komische Oper Berlin, conducts.

Vivier, Kopernikus; Staatsoper Berlin, January

Spoiler: I am working on a feature (another one) about the Quebec-born composer’s influence and the recent rise in attention his work have enjoyed. Kopernikus (subtitle: Rituel de Mort) is an unusual work on a number of levels; composed of a series of tableaux, there’s no real narrative, but an integration of a number of mythological figures as well as real and imagined languages that match the tonal colors of the score. This production (helmed by director Wouter van Looy, who is Artistic Co-Director of Flemish theatre company Muziektheater Transparant) comes prior ahead of a production the Canadian troupe Against the Grain (led by Joel Ivany) are doing in Toronto this coming April.

Vustin, The Devil in Love; Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Moscow Academic Music Theatre, February

It was while investigating the work of Russian composer and pianist Rodion Shchedrin that I learned about the work of contemporary composer Alexander Vustin — and became utterly smitten with it. A composer who previously worked in both broadcasting and publishing, Vustin’s opera is based on the 1772 Jacques Cazotte novel Le Diable amoureux, which revolves around a demon who falls in love with a human. Vustin wrote his opera between 1975 and 1989, but The Devil in Love will only now enjoy its world premiere, in a staging by Alexander Titel (Artistic Director of the Stanislavsky Opera) and with music direction/conducting by future Bayerische Staatsoper General Music Director Vladimir Jurowski.

Inside Opernhaus Zurich. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

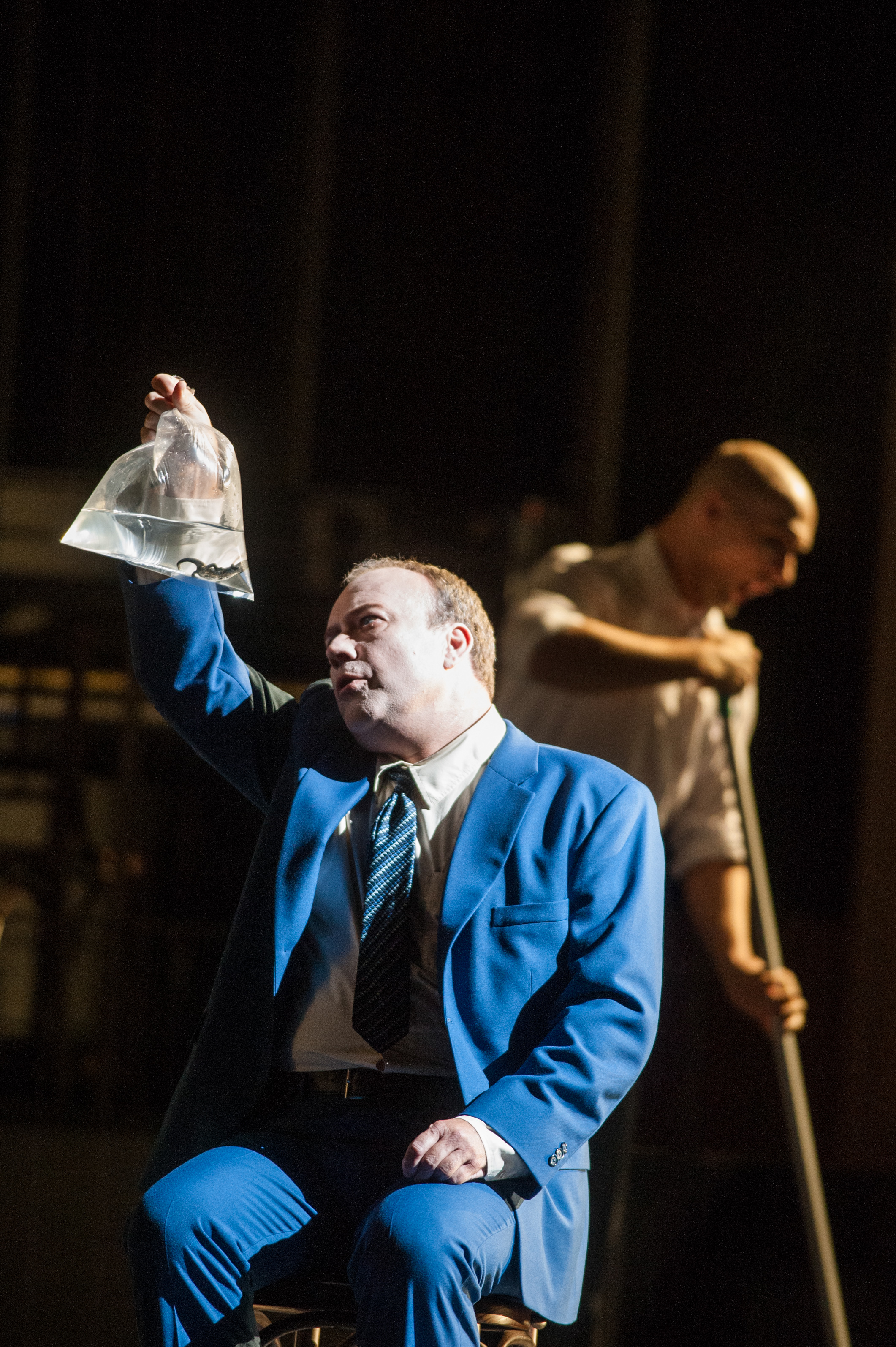

Ligeti, Le Grand Macabre; Opernhaus Zurich, February

The Opernhaus Zurich website describes this work, which is based on a play by Belgian dramatist Michel de Ghelderode, as “one of the 20th century’s most potent works of musical theatre.” It is also one of the most harrowing things I’ve seen; anyone who’s experienced it comes away changed. Directed by Tatjana Gürbaca (who’s directed many times in Zurich now), the work is, by turns, coarse, shocking, cryptic, and deliciously absurd. General Music Director Fabio Luisi (who I am more used to seeing conduct Mozart and Verdi at the Met) was to lead what Ligeti himself has called an “anti-anti-opera”; he’s been forced to cancel for health reasons. Tito Ceccherini will be on the podium in his place.

Zemlinsky, Der Zwerg; Deutsche Oper Berlin, February

Another wonderfully disturbing work, this time by early 20th century composer Alexander von Zemlinsky, whose “Die Seejungfrau” (The Mermaid) fantasy for orchestra is an all-time favorite of mine. Der Zwerg, or The Dwarf, is an adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s disturbing short story “The Birthday of the Infanta” and is infused with the sounds of Strauss and Mahler, but with Zemlinsky’s own unique sonic richness. Donald Runnicles (General Music Director of the Deutsche Oper ) conducts, with powerhouse tenor David Butt Philip in the title role, in a staging by Tobias Kratzer, who makes his DO debut.

Johann Christian Ludwig Lücke , Bust of a Grimacing Man with a Slouch Hat; 1740, Elfenbein; Bode Museum, Berlin. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Kurtág, Fin de Partie; Dutch National Opera, March

Among the many music happenings of late which could be called an event with a capital “e”, this one has to rank near the top. Ninety-one year-old composer György Kurtág has based his first opera on Samuel Beckett’s 1957 play Endgame. Premiering at Teatro Alla Scala in November, music writer Alex Ross noted that “(n)ot since Debussy’s “Pelléas et Mélisande” has there been vocal writing of such radical transparency: every wounded word strikes home.” Director Pierre Audi and conductor Markus Stenz (chief conductor of the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra) bring Kurtág’s painfully-birthed opera to Amsterdam for three (nearly sold-out) dates.

Handel, Poros, Komische Oper Berlin, March

A new staging of a rarely-heard work by legendary opera director Harry Kupker, Handel’s 1731 opera based around Alexander the Great’s Indian campaign features the deep-hued soprano of Ruzan Mantashyan as Mahamaya and the gorgeously lush baritone of KOB ensemble member Dominik Köninger in the title role. Conductor Jörg Halubek, co-founder of the Stuttgart baroque orchestra Il Gusto Barocco (which specializes in forgotten works) makes his KOB debut. The combination of Kupfer, Handel, and Komische Oper is, to my mind, very exciting indeed.

Southern Netherlands, Screaming Woman; late 16th century; Bode Museum, Berlin. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Shostakovich, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk; Opera National de Paris, April

A new production of Shostakovich’s passionate, brutal, and darkly funny opera from innovative director Krzysztof Warlikowski, whose creative and thoughtful presentations have appeared on the stages of Bayerische Staatsoper, the Royal Opera, Teatro Real (Madrid), and La Monnaie (Brussels), to name a few. He also staged The Rake’s Progress in Berlin at Staatsoper im Schiller Theater. Here he’ll be directing soprano Ausrine Stundyte in the lead as the sexy, restless Lady, alongside tenor John Daszak as Zinovy Borisovich Ismailov (I really enjoyed his performance in this very role at the Royal Opera last year), bass (and Stanislavsky Opera regular) Dmitry Ulyanov as pushy father Boris, and tenor Pavel Černoch as the crafty Sergei. Conductor Ingo Metzmacher is on the podium.

Berlioz, La damnation de Faust; Glyndebourne, May

Glyndebourne Festival Music Director Robin Ticciati leads the London Philharmonic and tenor Allan Clayton (so impressive in Brett Dean’s Hamlet, which debuted at Glyndebourne in 2017) as the doomed title character, with baritone Christopher Purves as the deliciously diabolical Mephistopheles, and French-Canadian mezzo-

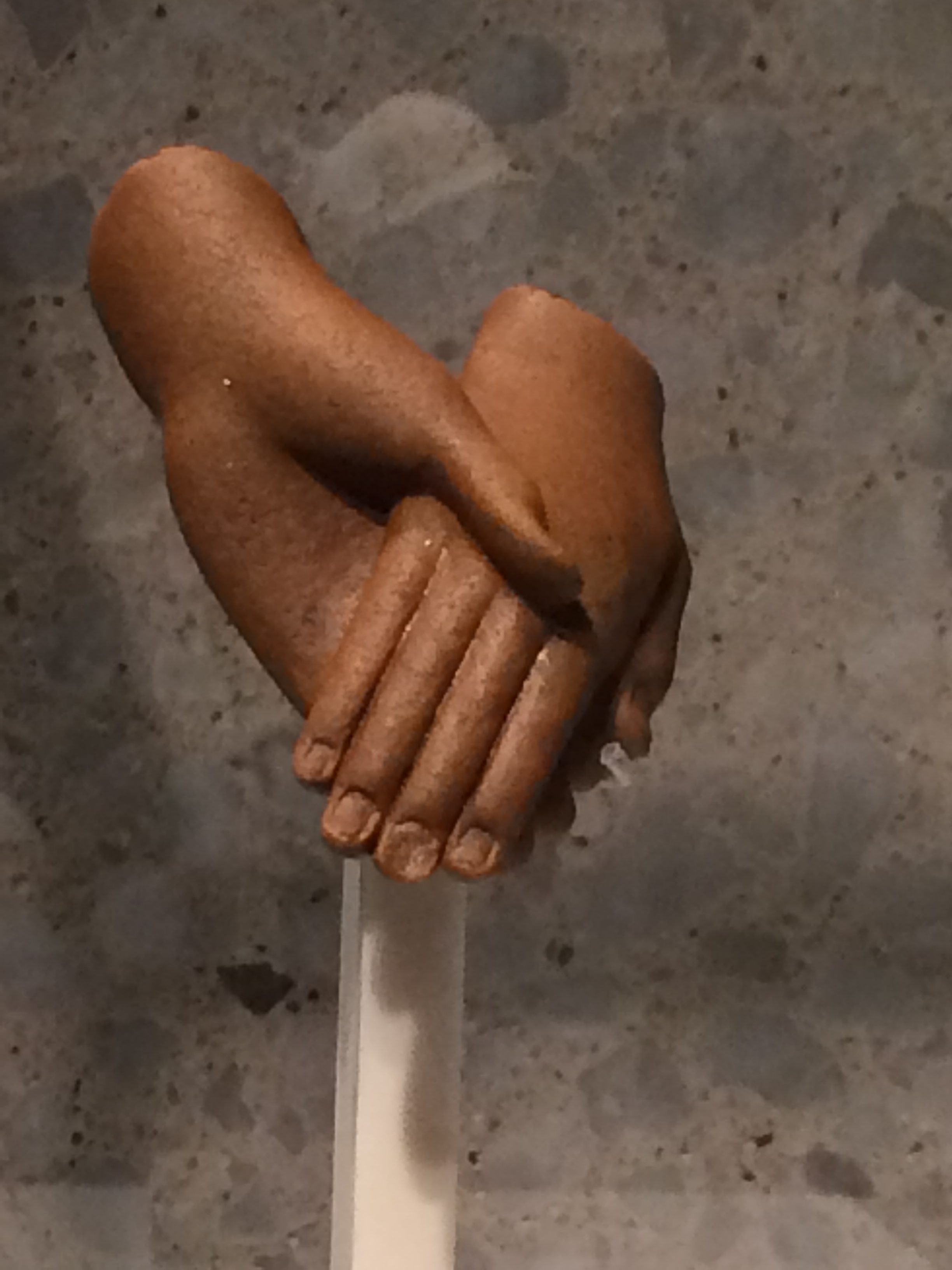

Pair of Hands from a group statue of Akhenaten and Nefertiti or two princesses; Neues Reich 18 Dynastie. At the Neues Museen, Berlin. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Gluck, Alceste; Bayerische Staatsoper, May

A new production of Gluck’s opera about self-sacrificing love with a fascinating backstory: after its publishing in 1769, a preface was added to the score by Gluck and his librettist which outlined ideas for operatic reform. The list included things like making the overture more closely linked with the ensuing action, no improvisation, and less repetition within arias. Alceste came to be known as one of Gluck’s “reform” operas (after Orfeo ed Euridice). Two decades later, Mozart used the same chord progressions from a section of the opera for a scene in his Don Giovanni, which Berlioz called “heavily in-inspired or rather plagiarized.” The Bavarian State Opera production will feature a solid cast which includes tenor Charles Castronovo, soprano Dorothea Röschmann, and baritone Michael Nagy, under the baton of Antonello Manacorda.

Handel, Belshazzar; The Grange Festival, June

Described on The Grange’s website as “an early Aida,” this rare staging of the biblical oratorio sees a cast of baroque specialists (including tenor Robert Murray in the title role and luminous soprano Rosemary Joshua as his mother, Nitocris) tackling the epic work about the fall of Babylon, and the freeing of the of the Jewish nation. Musicologist Winton Dean has noted the work was composed during “the peak of Handel’s creative life.” Presented in collaboration with The Sixteen, a UK-based choir and period instrument orchestra, the work will be directed by Daniel Slater (known for his unique takes on well-known material) and will be led by The Sixteen founder Harry Christophers.

Festival Aix-en-Provence, July

The final collaboration between Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht (and the source of the famous “Alabama Song”), Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny will be presented in a new production featuring the Philharmonia Orchestra, led by Esa-Pekka Salonen. Director Ivo van Hove (whose Boris Godounov at the Opera de Paris this past summer I was so shocked and moved by) helms the work; casting has yet to be announced. Music writer Rupert Christiansen has noted that it “remains very hard to perform […] with the right balance between its slick charm and its cutting edge.” Also noteworthy: the French premiere of Wolfgang Rihm’s one-act chamber opera Jakob Lenz, based on Georg Büchner’s novella about the German poet. (Büchner is perhaps best-known for his unfinished play Woyzeck, later adapted by Alban Berg.) Presented by Ensemble Modern, the work will be helmed by award-winning director Andrea Breth and conducted by Ingo Metzmacher. This summer’s edition of the festival marks Pierre Audi’s first term as its new Director, and all five productions being staged are firsts for the fest as well.

Sphinx of Shepenupet II, god’s wife of Amon; late period 25th Dynasty, around 660 B.C.; Altes Museum, Berlin. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Enescu,Œdipe; Salzburger Festspiele, August

The Romanian composer’s 1931 opera based on the mythological tale of Oedipus is presented in a new production at the Salzburg Festival and features a stellar cast which includes bass John Tomlinson as the prophet Tirésias, mezzo-soprano as Jocasta, mezzo soprano Clémentine Margaine (known for her numerous turns as Bizet’s Carmen) as The Sphinx, baritone Boris Pinkhasovich as Thésée, and baritone Christopher Maltman in the title role. In writing about Enescu’s score, French music critic Emile Vuillermoz noted that “(t)he instruments speak here a strange language, direct, frank and grave, which does not owe anything to the traditional polyphonies.” Staging is by Achim Freyer (who helmed a whimsical production of Hänsel and Gretel at the Staatsoper Berlin), with Ingo Metzmacher on the podium.

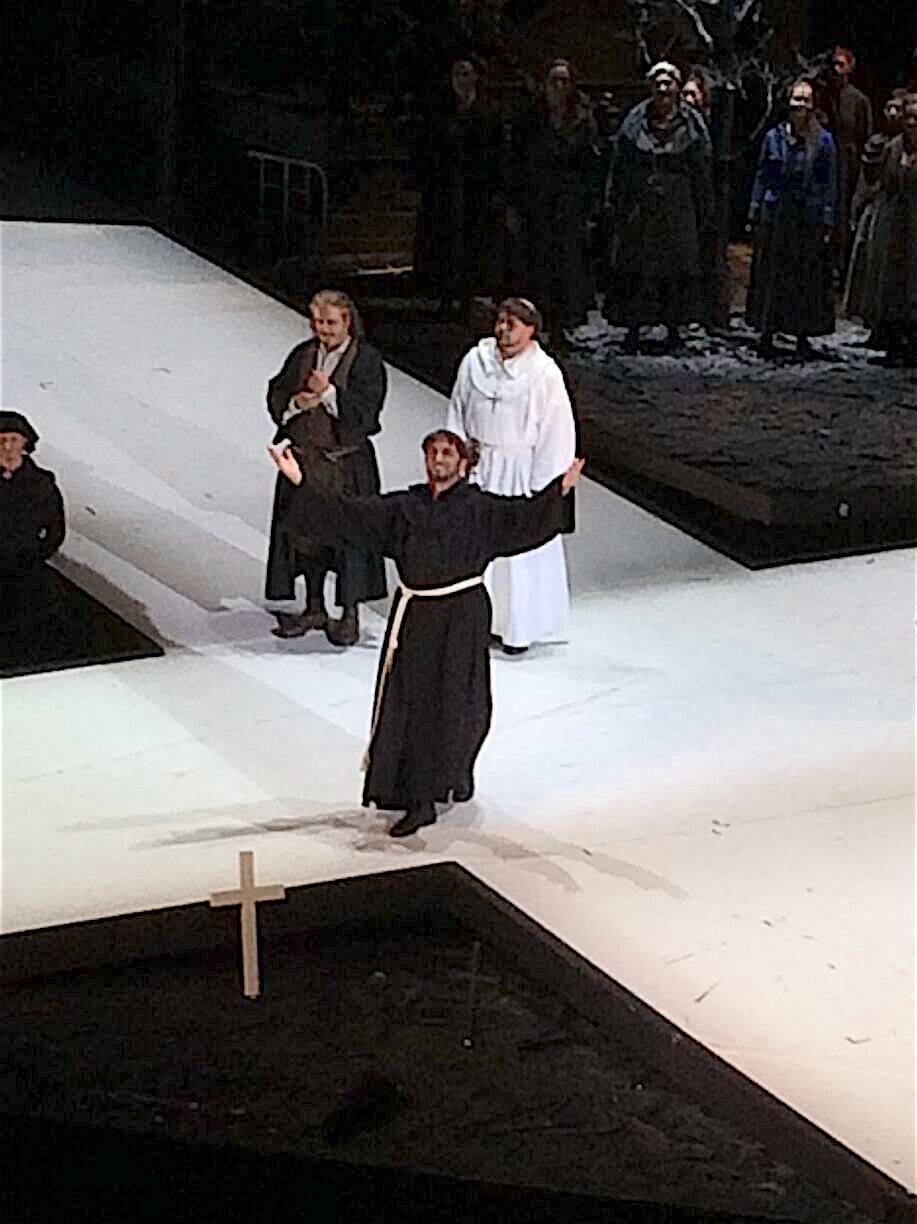

Schoenberg, Moses und Aron; Enescu Festival, September

In April 1923, Schoenberg would write to Wassily Kandinsky: “I have at last learnt the lesson that has been forced upon me this year, and I shall never forget it. It is that I am not a German, not a European, indeed perhaps scarcely even a human being (at least, the Europeans prefer the worst of their race to me), but that I am a Jew.” The ugly incident that inspired this would result in his mid-1920s agitprop play Der biblische Weg (The Biblical Way), from which Moses und Aron would ultimately spring. Essentially a mystical plunge into the connections between community, identity, and divinity, this sonically dense and very rewarding work will be presented at the biennial George Enescu Festival, in an in-concert presentation featuring Robert Hayward as Moses and tenor John Daszak as Aron (a repeat pairing from when they appeared in a 2015 Komische Oper Berlin production), with Lothar Zagrosek on the podium.

Post-opera strolling in Wexford. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Wexford Festival Opera, October

It’s hard to choose just one work when Wexford is really a broader integrative experience; my visit this past autumn underlined the intertwined relationship between onstage offerings and local charms. The operas being presented at the 2019 edition include Der Freischütz by Carl Maria von Weber, Don Quichotte by Jules Massenet (which I saw, rather memorably, with Ferruccio Furlanetto in the lead), and the little-performed (and rather forgotten) Adina by Gioacchino Rossini, a co-production with Rossini Opera Festival. The latter will be paired with a new work, La Cucina, by Irish composer Andrew Synnott.

Strauss, Die ägyptische Helena; Teatro Alla Scala, November

A reimagining the myth of Helen of Troy (courtesy of Euripides) sees Paris seduce a phantom Helen created by the goddess Hera, while the real thing is held captive in Egypt until a long-awaited reunion with her husband Menelas. In a 2007 feature for the New York Times (published concurrent to a then-running production at the Met), music critic Anthony Tommasini characterized Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s libretto as “verbose and philosophical,” and posed questions relating to Strauss’s score thusly: “Is a passage heroic or mock-heroic? Opulently lyrical or intentionally over the top?” I suspect those are precisely the questions the composer wanted to be raised; he questions not just the tough questions around intimate relating, but ones connected with audience and artist. The piece features some breathtaking vocal writing as well. Sven-Eric Bechtolf (whose Don Giovanni I so enjoyed at Salzburg in 2016) directs, and Franz Welser-Möst leads a powerhouse cast that includes tenor Andreas Schager, baritone Thomas Hampson, and soprano Ricarda Merbeth as the titular Helena. This production marks the first time Die ägyptische Helena has been presented at La Scala.

Oskar Kallis, Sous le soleil d’été; 1917, on loan to Musée d’Orsay; permanent collection, Eesti Kunstimuuseum, Tallinn.

Messager, Fortunio; Opéra-Comique, December

I freely admit to loving comédie lyrique; the genre is a lovely, poetic cousin to operetta. Fortunio, which was premiered in 1907 by the Opéra-Comique at the Salle Favart in Paris, is based on the 1835 play Le Chandelier by Alfred de Musset and concerns a young clerk (the Fortunio of the title) caught in a web of deceit with the wife of an old notary, with whom he is enamored. Gabriel Fauré, who was in the opening night audience (along with fellow composers Claude Debussy and Gabriel Pierné) noted of André Messager (in a review for Le Figaro) that he possessed “the gifts of elegance and clarity, of wit, of playful grace, united to the most perfect knowledge of the technique of his art.” This production, from 2009, reunites original director Denis Podalydès with original conductor Louis Langrée. Paris en décembre? Peut-être!

Auguste Herbin, Composition; 1928, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.

This list may seem extensive, but there’s so much I’ve left out — festivals like Verbier and Les Chorégies d’Orange, houses like Wiener Staatsoper and Teatro Real, outlets in Scandinavia (Den Norske, Royal Swedish Opera, Savonlinna) and Italy (Pesaro, Parma) and the UK (Aldeburgh, Garsington, ENO, and of course the Royal Opera). It’s still too early for many organizations to be announcing their upcoming (September and beyond) seasons; I’m awaiting those releases, shivering, to quote Dr. Frank-n-furter, with antici…pation.

And, just in the interests of clarifying an obvious and quite intentional omission: symphonic events were not included in this compilation. The sheer scale, volume, and variance would’ve diffused my purposeful opera focus. I feel somewhat odd about this exclusion; attending symphonies does occupy a deeply central place for me on a number of levels, as it did throughout my teenaged years. Experiencing concerts live is really one of my most dear and supreme joys. I may address this in a future post, which, as with everything, won’t be limited by geography, genre, range or repertoire. In these days of tumbling definitions and liquid tastes , it feels right (and good) to mash organizations and sounds against one another, in words, sounds, and spirit.

For now, I raise a glass to 2019, embracing adventure — in music, in the theatre, in life, and beyond. So should you. Santé!