Performers at the Cantus Domus presentation of St. Matthew Passion in Berlin take bows. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

Easter Weekend inspires reflections on awakenings, growth, a sense of the new and fresh emerging at last. There are a number of works within classical music that deal directly with Easter, Handel’s Messiah being perhaps the most famous (programming it over the Christmas season is forever a pet peeve), but just as equally Bach’s Passions, which are widely presented and performed in halls across Europe in the weeks and months leading up to Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Easter Sunday.

During a trip to Berlin earlier this month, I attended a very special performance of St. Matthew Passion, one which asked something more than solitary contemplation; rather, the Baroque work conjured unique meditations on the convergence of heaven and earth, sound and silence, spirit and flesh, through the act of actually singing it. Cantus Domus, a choral group based in Berlin who specialize in conceptual presentations, have a number of illustrious performances under their belts, performing an array of repertoire that spans from the Renaissance to today. Formed in 1996, the group has performed works by Bizet, Mahler, Mendelssohn, and Bach, and have also enjoyed numerous appearances at the annual German open-air music fest Haldern Pop Festival. Lets you think they only work within the classical idiom, think again: Cantus Domus have collaborated with a good number of contemporary music artists including Bon Iver, The Slow Show, and most famously, Damien Rice. For the recent presentation of St. Matthew Passion, they worked with renowned period instrument troupe Capella Vitalis Berlin, creating a community event in which the act of singing became a salute to its original presentation, as well as a beautiful way of fusing theatricality with spirituality.

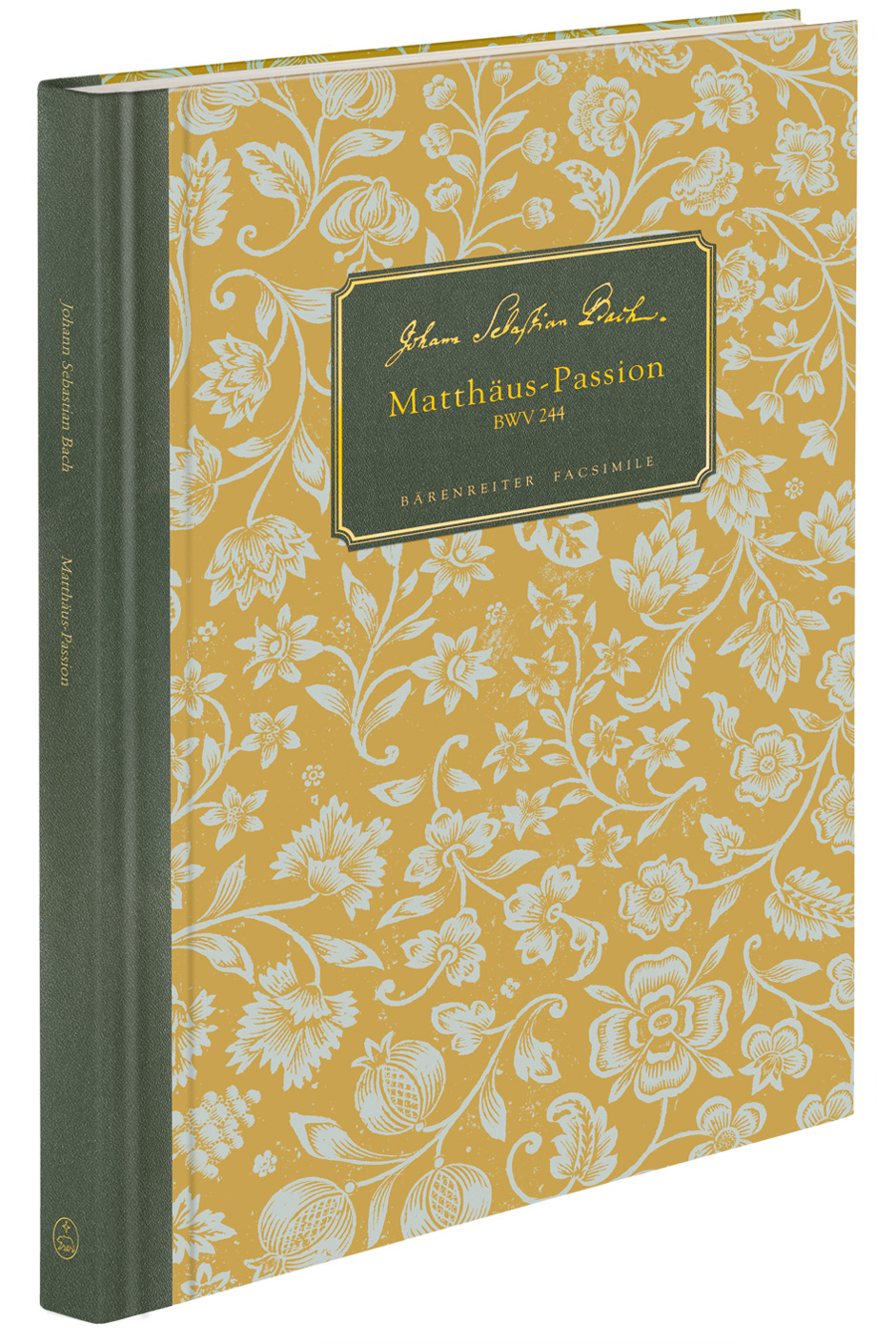

The Passion, written in 1727, was, as conductor and musicologist Joshua Rifkin rightly notes, “the longest and most elaborate work that (Bach) ever composed. It would appear that he saw significant phase of his life drawing to a close and took the occasion to produce a work that would synthesise and surpass all that he had previously done in the realm of liturgical music.” It only began to gain in popularity a full eight decades after Bach’s death (in 1750), thanks to the efforts of a young Felix Mendelssohn, who presented the work in Berlin in 1829. It is one of numerous sacred pieces Bach wrote during his lengthy tenure as director of religious music at Thomaskirsche (St. Thomas Church) in Leipzig. Based on the Gospel of Matthew, Bach worked with poet Christian Friedrich Henrici (known as Picander) for the libretto, which explores the final days of Jesus, ending with Christ’s burial. It features a fascinating interplay of musical writing between four soloists (soprano, alto, tenor, and bass) and orchestra which features, among many creative musical choices, two lead violins in the string section. “The St. Matthew Passion, the final glory of one of the most productive periods in Bach’s life,” writes Rifkin, “holds a special place in his artistic legacy.”

At the end of February, Cantus Domus held a public rehearsal before the main event, which I attended one cold, bright Saturday morning. This was, I quickly realized, more than a jovial sing-a-long; these were serious music-lovers from every walk of life engaging in what was clearly perceived as an act of commitment and consecration. The act of singing, with a roomful of strangers, in a language I don’t speak, reading music — an act I had long believed to be a thing I wasn’t smart enough to do with any real talent — was a deeply moving one. The formal performance one week later magnified this feeling; sitting in Wisniewski’s wonderfully intimate chamber hall, encircled by ever-mobile performers and an enthralled public, the music was a communal prayer; the voices of those beside, behind, and around me created transcendence which defies easy description. The strong vibrations of breaths and voices through seats, floors, hands, paper… was strange, shocking, beautiful, and the overall experience was and remains one of the most precious and profound ones of my life.

The cover to a special edition of the score to St. Matthew Passion. (Score / photo: Bärenreiter)

I spoke with two people from Cantus Domus earlier this month in Berlin. Ralf Sochaczewsky is conductor and Artistic Director of Cantus Domus; he has a long list of credits to his name in both the classical and contemporary music worlds, including gigs with the Komische Oper, the Bolshoi Theater, the London Philharmonic, and the Konzerthaus Berlin Orchestra. Carolin Rindfleisch is a member of the Cantus Domus board and a singer herself; she came up with the presentation concept for St. Matthew Passion here and was its dramaturge. We had a wide-ranging chat just before rehearsals about the work, its influences, and why presenting it, with a full score but without tricks or gimmicks, opens the door to something very special.

Where did the idea come from to do an interactive performance of the St. Matthew Passion?

Caroline: We’ve done something like this before, with the St. John Passion in 2014. When Bach wrote the Passions, people knew the chorales very, very well — they were part of daily life; people knew the texts by heart, the melodies by heart. They were musical elements that brought everyone together. Even though people didn’t sing it, they were involved immediately because they knew it so well, and it’s something which is hard to recreate nowadays because most people don’t have this kind of religious involvement or knowledge of texts or melodies with such immediacy anymore. So if you invite them to rehearse with you, and to sing them during the concert, we hope to create the same kind of involvement, which was the original purpose of the chorales.

This music is associated with a very sacred time on the Christian calendar. What’s it like to bring it into secular world now?

Carolin: I think the focus might shift a bit. Our lives are not focused so much on religion, it’s not part of our daily lives that much — but the story behind (this work) has so many different levels and dimensions, and so many different things people can relate to, even if they can’t relate to the religious aspect of it. It’s also a story of how groups and individuals relate to each other, how people treat each other, how relationships between individuals develop, and what problems there may be. There are so many levels people can relate to. If you ask people to sing the chorales with you, then they have to relate in a different way to the piece — they have to position themselves. If you say something out loud, you can’t distance yourself from it that much anymore, you have to think, “How does this relate to me? What am I singing here?” If you only listen, it’s much easier to cut yourself off from a part that doesn’t agree with your worldview — but if you say it loud yourself, you have to think, “What is my position within this piece?”

Singing is such an intimate act that makes some people self-conscious — they think, “I can’t sing!” and moreover, “I can’t possibly sing Bach!”

Ralf: You will!

What do you think the audience gets out of these kinds of experiences?

Ralf: We did a similar (singing) project four years ago with the St. John Passion, and what the audience told us after the concert was that they were deeply involved. One woman told me that her relationship to her religion changed because of the reflection and the meditation while singing — it touched her so deeply in a way she couldn’t believe. So I think maybe many people will experience this at a deep level of feeling and believing.

Carolin: It’s not “Look at me singing!” — and even if you don’t want to sing yourself, if people are sitting all around you participating it creates an atmosphere where you can’t but relate to it in a way.

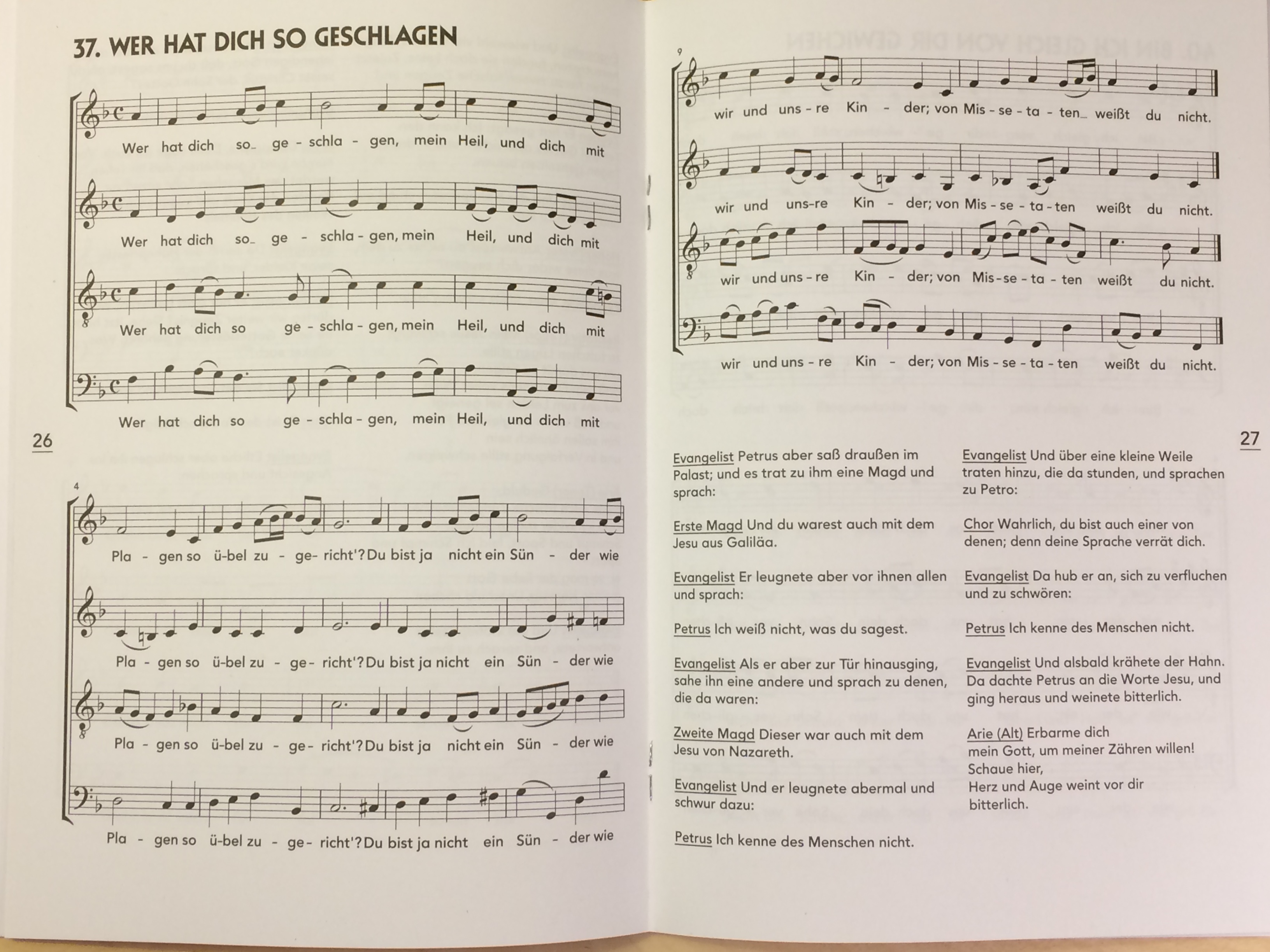

A portion of the program from the Cantus Domus presentation of St. Matthew Passion in Berlin. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

How do you keep the drama within the score? Is it important?

Ralf: Absolutely. I think the person of Judas is maybe the most interesting part in this Passion. When you perform it you have to find a position about the guilt of Judas: is he maybe a hero? Is he maybe the Edward Snowden of this? What the music says and what the libretto says is a bit ambivalent. So we will try to find a solution to make later what Judas means to us, but…

Carolin: The Passions have a lot of changing places, between intimacy and public life. You can make the public experience those different atmospheres by how close you get to them or how much you concentrate the action into one corner, or spread it into all over, especially in the Philharmonie Chamber Music Hall — it’s such a nice room. You have the stage and the places where the audience sits, but you also have places you can position soloists at different corners of the room, and make visible how close or how far they are, and how they relate to each other, and what’s really powerful about working with a choir scenically onstage is that if even thirty or, say, sixty people do a very tiny little thing at the same time, it’s incredibly powerful but still subtle. You don’t have to have someone tearing his heart out…

Declaiming?

Carolin: Exactly, but you have sixty people that maybe do a specific gesture at the same time, and the whole focus shifts into another direction, and this is giving little guiding posts to where the action moves in the room, so we move very little, but the action shifts and the focus shifts in the room, and this can be a really interesting way of preserving the drama while not really acting.

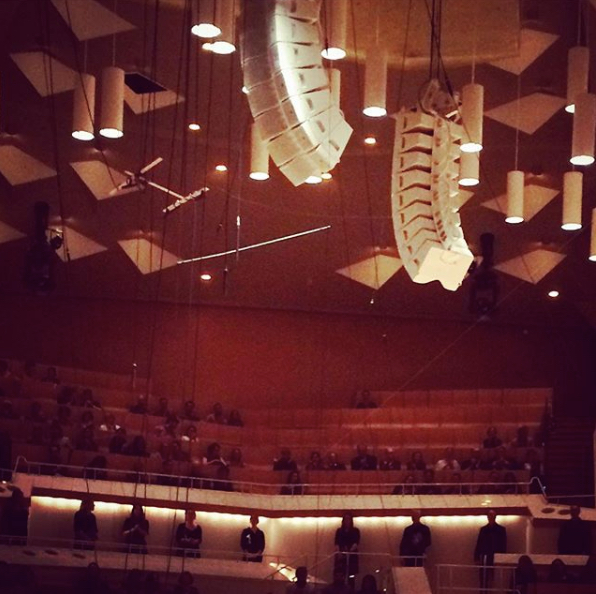

The Philharmonie Chamber Hall is encircled by performers at the close of Cantus Domus’s St. Matthew Passion in Berlin. (Photo: mine. Please do not reproduce without permission.)

Ralf: We just have small hints! Also you find interesting things in the music. For example, the opening of the second part is text from the Song of Solomon, sung by the choir: “Where has my Jesus gone?” The outer part is relating to Petrus, so you have a quite direct connotation it’s Petrus who’s talking. But in the earlier version (of the work) it was sung by the bass soloist, the aria section that is, which is related to Judas, which is interesting. I think it was meant by Bach, in the early version, that it’s Judas who sings, “Where has my Jesus gone?” And the chorus sings the Song of Solomon, it’s a very intimate and like … a love song. In many places in the bible, it’s said Judas was the most beloved of Jesus, and I think this is something which is really interesting in the relationship between Jesus and Judas, which gives a different color to this man, who in our perception is a very bad man.

We even have the term “the Judas kiss” because of it.

Ralf: Yes but even this kiss, it’s still a kiss!

… which some believe is the ultimate betrayal of intimacy.

Ralf: I’m not sure that this is the only way of interpreting this kiss. Bernard of Clairvaux, a very important clerical figure and one of the most important mystics, preached about the Song of Solomon, especially the symbol of the kiss, and many texts in the Passion from the chorales go back to Clairvaux. There’s a close net of mysticism in (the Song of Solomon). So the Judas kiss, in a way, when you look at it from the point of view of Clairvaux and directly after that, within this Solomonic love song, it means something different.

I’ve always found inclusion of portions of the Song of Solomon sends a message about the links between spirituality, sensuality, intimacy, and meditation — things that can get lost because of the tendency to present spiritual experience within a strictly defined religious framework.

Ralf: If you look deeper into (St. Matthew Passion) you will find real human beings who existed in the 18th century, and who exist in the same way today. And Judas needs to betray him, otherwise the story couldn’t work: no cross, no Christianity. It’s clear Judas has to do it, in a way, it’s fate. But on the other hand, you have the people and they do not understand, they condemn him, many people condemn. It’s a really interesting relationship. Also, Petrus is a very modern person, he’s very strong, a powerful man, but in the important moment, he’s very weak and he has fear, and he does not know how to behave. He’s uncertain what to do, which we all recognize. So this is the aim of our performance, that you understand while singing and reflecting, reflecting while singing, that you are Petrus… maybe you are also Judas… maybe you are also Pilatus, who washes his hands like, ”I have nothing to do with this.”

Through singing, you taking these human dimensions and complexities into your own body. Do you think you ask a lot of your audiences?

Carolin: Yes, we know we do, but I think it’s a really good thing to do. You don’t have to do it all the time, there are performances that are more relaxed and have a more loose connection to the audience, but it’s refreshing to ask an audience to commit.

It’s unique to find a presentation of a Baroque work that asks its audience to have a direct relationship with both the score and its spiritual subtext without feeling the need to use tricks or gimmicks.

Caroline: There’s a point which is really important for us as a choir: we have the feeling that with every project we do we grow a little, because we demand something we haven’t done before or haven’t done in this exact way. And this is something you can offer to audience as well in this fashion: you demand a lot of them. But if you, as an audience member, are willing to commit to it, it gives you something you hadn’t experienced before.