Photo: Hans Morren

Lieder, or art song, is one of those cultural things that took me a while to appreciate.

Only fleetingly exposed to the art form as a child by my opera-loving mother (whose tastes leaned very heavily Italian), I felt, for a long time, that lieder was simply too dense, too serious, and frankly, too… smart for me. I may have made it something of a mission the last few years to fight against long-held (and frequently incorrect) perceptions around the approachability of classical music, but I freely admit to having held some of them myself. For me, lieder was daunting. Then I went to Berlin (a lot), and heard it live (a lot, and very beautifully), and my love affair with lieder began in earnest: not dense but rich, not serious but thoughtful, and yes, unrelentingly brainy and intellectual, but equally soulful and very romantic. Lieder is, like many of the things I’ve come to cherish, a beautiful marriage of head and heart, intelligence and intuition, the divine and the earthy. Much as humans love to place things in tidy mental boxes, there are some things — sometimes the most meaningful things — which, by their nature, live in and between and around several boxes at any given moment; I’m beginning to think this is the way life, love, and culture (and some odd combination of them) should, in fact, be most of the time. The trick is making peace with it all.

Good lieder performances make that job easy. For those new to the art form and curious, I’d recommend listening to recordings by the late, great lyric baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, as well as by another German singer, one very much alive and busy, tenor Christoph Pregardien. He’ll be performing a concert of Mahler and Schubert works in Toronto tonight, with renowned pianist Julius Drake, as part of the annual Toronto Summer Music Festival. With a career spanning over four decades and several hundred recordings and live performances, Pregardien is one of those rare artists who brings a very innate yet approachable creativity to whatever medium he’s a part of. His performance as the title character in a 2005 production of Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito at Opéra National de Paris had an immediacy which brought the rich inner life of the beset Emperor to life, imbuing Mozart’s rich score with both gravitas and grace. Likewise, Pregardien’s recording of Schubert’s famous “Erlkönig” ferociously captures the total terror so inherent to the piece, as well as an enticing, manic lyricism within (and between) each note and breath. Pregardien understands drama in both broad and personal senses, and he is singularly gripping in his combination of the two.

We recently shared a wide-ranging conversation exploring the whys and wherefores of recital as art form, the challenges (or not) of bringing it to younger audiences, and why performing “naked” is so important for singers.

You’re doing an interesting recital with works by Mahler and Schubert. Do you see connections between the two?

Both of them are, for me, the most important lieder composers, and they have similarities — that’s why I put this program together If I listen to Mahler’s songs, and to Schubert’s songs, I have the immediate feeling that they grab the text and transform it into music which, for me, has a very intense and direct emotional height. And while with other music I’m using my brain to understand it, it’s not necessary for me to understand Mahler and Schubert songs the same way.

It’s an understanding of the heart…

I think, yes.

Recitals are such a big part of your career, and I’m curious what contrasts you note between European and North American audiences in doing them.

Many people who left Germany in 1930s and 1940s supported a lot of the German repertoire, especially lieder, and now of course because it’s been a long time since the Second World War was over, they’re dying. We have a great tradition of art song in Europe, especially the German-speaking part, and the same exists in England and in France and the Netherlands, so I have a good feeling about the future of recitals. I think that the reason why the English-speaking part of North America has difficulty with recitals… yes, in our time people are not used to concentrating for long periods of time, but on the other hand, I see many younger people attending recitals, and they are normally very enthusiastic about it afterwards. The problem is giving them the possibilities for the first step. There is also a huge number of young singers coming up who present song in a different context.

How so?

For example, by talking to the audience, by discussing themes with them, by preparing them for the music. Also, I think many people fear the atmosphere of the recital hall, with two men or a woman and a man in tails. Also I think programming has changed. And, so as far as I can see since I am onstage — which is now about 40 years! — everybody has complained about “white heads” in the audience, but it has been like this all the time. It’s question of generations, because younger people, when they are between the ages of 20 and 40, they are living their lives, bringing up families. Later, when they are a little bit older and with grey hair, they get more time to walk to concerts and to visit recitals. I can see that myself; I have three adult children, one of my sons (Julian) is a singer too. My elder son is now 36 and he was not very interested in classical music, but during the last five or six years he started to go more into classical concerts — not only recitals, but also opera and orchestral concerts. I think of course you have to teach young people that next to pop music and rock music there is classical music, and you need more attention and more wisdom to receive classical music, because it’s more complex.

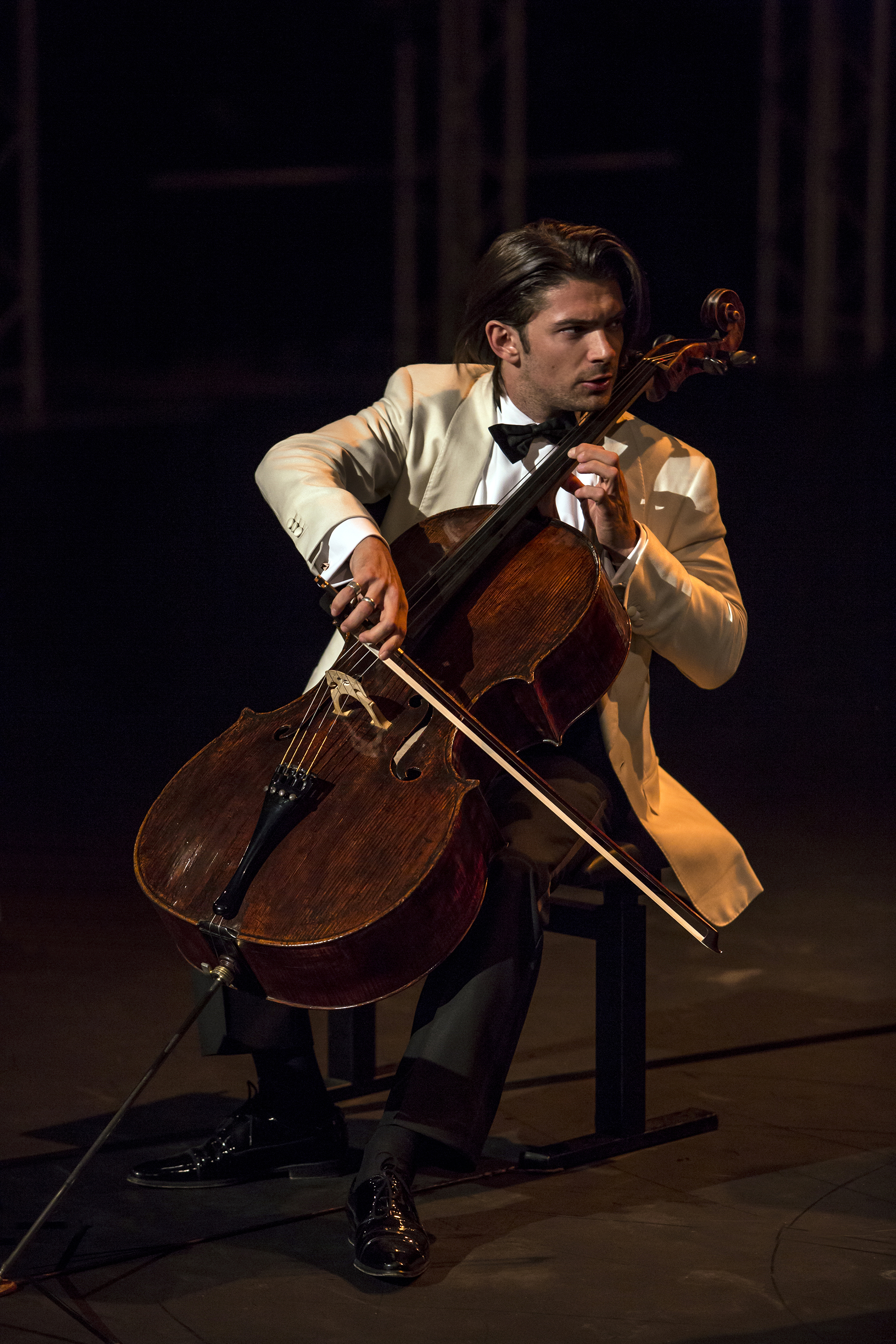

Photo: Jean-Baptiste Millot

But the attainment of that wisdom need not be intimidating.

Why should wisdom be intimidating? Young people are learning so much at school, many things which, from my point of view, are not that important — they’re not taught enough about how to handle money for example, or taught how to cook, and they’re not taught about music and cultural life.

Artist Olafur Eliasson said in a recent interview that culture was just being used for promotion now, which I found interesting to consider within context of recital work, because it’s not an art form you can necessarily reduce that way — it turns against such reduction by its very nature. Recitals are a form you have to spend time with, and which force you to spend time with yourself.

Yes, it involves everything which goes deeper into the real things of life, which are not always nice; life is not only joy, life is also struggle, and death. I think what draws people is that they can experience all these normal, natural emotions — longing, desire, love, hate, all these very important emotions — in a recital. In our time it’s so difficult to experience that in normal life.

Is that why recitals matter?

It’s one of the reasons, yes. We have a cultural heritage we have to give to our children as well, and I think as we have museums for paintings and for sculptures and architecture, we have, as human beings, a longing for tradition and for giving good things to their children, and I think classical music, which started in medieval times and goes to the 21st century, it’s a huge and important heritage. What is also important is that it is a social event to make music yourself, not only listening to music but making music yourself; the voice is the most natural and first instrument of all.

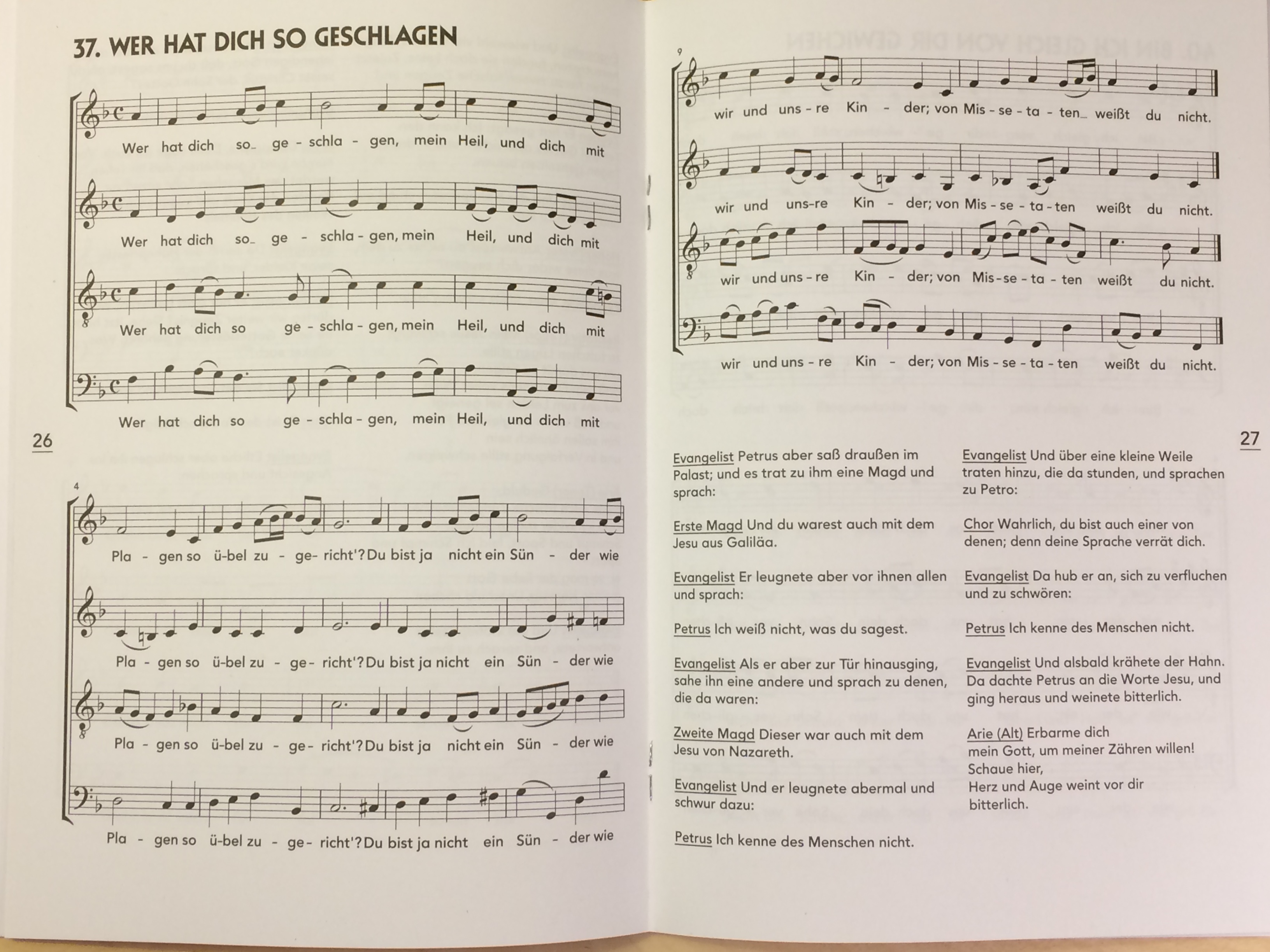

I noted that in attending an interactive performance of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion live in Berlin this past winter. It was extremely moving, this act of singing communally, yet it was totally normal, not an Instagram moment at all, but simply something people were doing together as part of everyday life.

It’s dying out in Germany too, the choral tradition, because young people don’t have time anymore, they have many hobby horses, a big schedule. I have two smaller children, 8 and 10, and they started to play an instrument, and of course as parents you have to be behind them and say, “You have to take your twenty minutes or half-an-hour to practise your instrument” and they do it — but you have to convince and remind them.

Sometimes there are singers who need to be convinced to do recitals as well. Why do you think that is?

You don’t have a costume or theatre or an orchestra, you’re nearly naked onstage! For me it was a very natural thing to do, and I have a huge experience with it now, but I can understand singers who are used to having an orchestra in their back or in their front. If you’re doing an opera, from time to time you can go offstage, eat something, drink something, rest a little bit; during a recital you are onstage for one hour or hour and a half and you have to show everything you are able to do. You are exposed. But I love the feeling to be very close to my audience. I love the feeling that I can draw them into certain moods, that there’s a certain sensitivity to the personality on stage.

Photo: Marco Borggreve

A singer has to be real for that moment.

Yes. That’s the most important thing for a singer, be it an opera or oratorio or concert singer: you have to be authentic. The moment when you deliver your voice to an audience, it must make sense, and it must have meaning. We are the only musicians with text, and you have to communicate and give your soul, or parts of your soul, to your audience, in order to grab them. We have the ability, with this beautiful instrument, to draw their attention in a unique way.