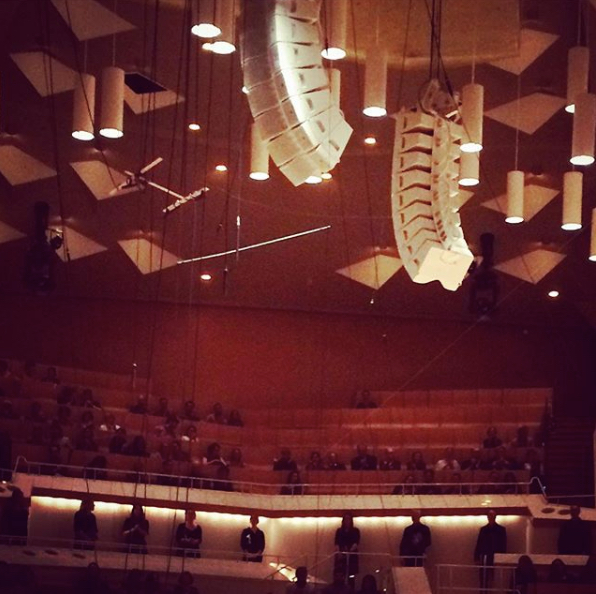

Sir George Benjamin leads the Berlin Philharmonic at Musikfest Berlin 2018 (Photo: (c) Kai Bienert)

Attending the Berlin Musikfest is quickly becoming something of a habit. Since my first experience with the event last year, I’ve become captivated by its varied and very rich programming, which features local organizations (including the Rundfunk Sinfonieorchester, the Konzerthaus Orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic, and the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester), plus a number of important chamber groups, vocal outfits, and an assortment of stellar visiting orchestras, including the Royal Concertgebouw Amsterdam and Boston Symphony Orchestra recently.

What I love about Musikfest is that it is so unapologetically varied; there is no sense of needing to appeal to a so-called “mainstream” base, because the term simply doesn’t apply. Thus the programming is what one might term adventurous, exploratory, just plain smart — and features many modern and/or living composers, like the concert given by the Berlin Phil this past weekend, led by conductor/composer (and Composer in Residence for the 2018-2019 season) Sir George Benjamin. Saturday’s performance was a chewy, thoughtful presentation that examined notions of time, impermanence, and various states of perception. Like so much of the programming at Musikfest, the concert was a thought-provoking examination of how we experience music, in time and space, according to personal and historical perceptions, and how we live in, around, and outside of sound itself.

The program opened with the work of composer/conductor Pierre Boulez. At his passing in early 2016, Boulez had affirmed his place as one of the most important artists in twentieth century music. His experimental, and frequently ground-breaking approach helped to shape so very many composers and artists (Benjamin included) who followed. “Cummings ist der Dichter” (“Cummings is the poet”) is a 1970 work that imitates through sound what the poet ee cummings attempted to achieve in text. As Anselm Cybinski’s fine program notes remind us, “(p)erception is broken up into multiple perspectives; the possibilities for reading and understanding increase.” While the work can be jagged, there is a majestic beauty at work, an undeniable forward momentum despite “its gestures seem(ing) discontinuous and spontaneous.”

Benjamin thoughtfully emphasized these multiple perspectives through careful (indeed, loving) emphasis on the relationship between harps, strings, and voices (especially female) via ChorWerk Ruhr. Their melismatic vocalizing was hugely complemented by the tremulous bass work of Janne Saksala, which made for a gorgeous fluidity that nicely contrasted the many crunchy chords and dissonant jolts. Benjamin himself has a gentle approach that is simultaneously intuitive and narrative-driven, equal parts heart and head, perhaps reflecting his own operatic considerable (and rightly celebrated) history. This gentle force would shape and define the program overall, becoming especially discernible in the final work of the evening by Benjamin himself.

Cédric Tiberghien performs with the Berlin Philharmonic as part of Musikfest Berlin 2018 (Photo: (c) Kai Bienert)

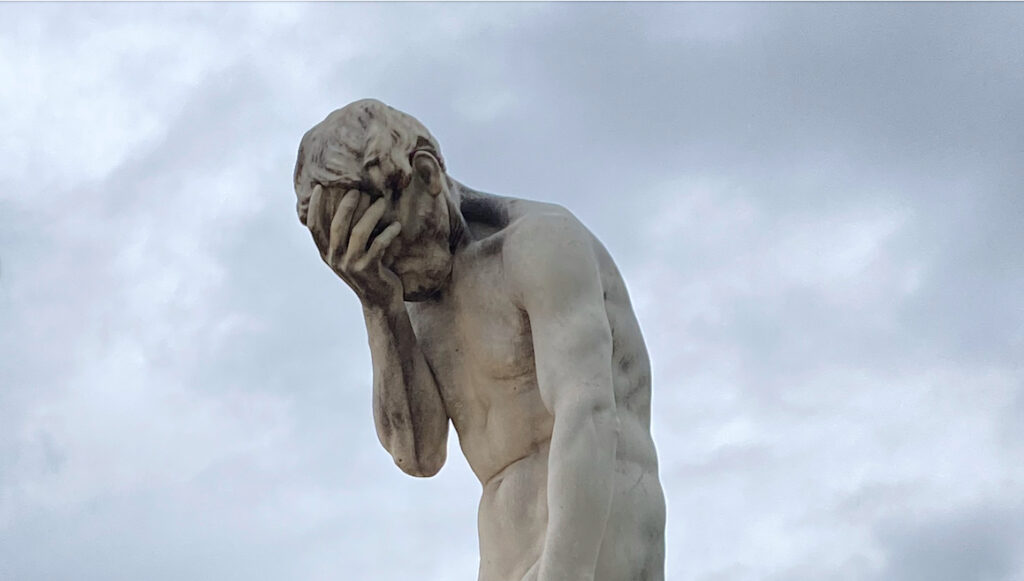

Before then, the audience was treated to a ravishing performance of Ravel’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra in D major for the left hand, with French pianist Cédric Tiberghien. The piece, written between 1929 and 1930, was commissioned by concert pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who had suffered grave injury in the First World War, losing his right arm as a result. The concerto is a fiercely virtuosic work which Ravel himself described as being in “only one movement” though its slow-fast-slow structure and allusions to various other works (some by the composer himself) make it far more thoughtful than its title might suggest.

The opening, as sonically luxuriant as any from Ravel’s 1912 “symphonie chorégraphique” Daphnis et Chloé, featured beautiful bass and bassoon work, with Benjamin emphasizing sensuous tone and phrasing. The build to Tiberghien’s virtuosic entrance dripped with drama; Benjamin pulled a sparkling ebullience from the orchestra, with ringing strings and boisterous if well-modulated brass and woodwinds. A syncopated section featuring violas, cellos, and bassoons could so easily have been played cartoonishly (and in fact, frequently is), but the maestro avoided any easy sonic trappings, focusing on the probing heart beneath the plucky lines, with the piano as a blended and equal partner.

Sir George Benjamin with Cédric Tiberghien (Photo: (c) Kai Bienert)

In this he and the orchestra were matched by Tiberghien’s energetic playing, his laser focus never obscuring or erasing his highly poetic approach. The young pianist seemed less concerned with showing off his (clear) virtuosic talent than with coaxing color, modulation, a refined texture (clarified to a remarkable degree in his encore, “Oiseaux tristes”, the second movement of Ravel’s piano cycle Miroirs). The clear sonic references contained within the Concerto to Ravel’s famous “Boléro” (premiere in 1928), as well as to Gershwin works (especially “Rhapsody in Blue”, premiered in 1924) were made clear enough without belaboring the obvious; Benjamin emphasized percussion (as he did throughout the evening), with an insistent pacing echoed by cellos and bass, making the sound more akin to a grinding war machine than flamenco or jazz, a clear reference to the history of the piece’s commissioner and first performer.

The contemplative nature of the performance also underlined the temporal nature of the sound experience in and of itself, and how it might be altered with the use of only one limb; such contemplations around temporality, perception, and one’s direct experience of sound would emerge as a dominant theme of the evening, highlighted in Ligeti’s Clocks and Clouds for 12-part female choir and orchestra, written in 1972-73, and a reference to a lecture given by Karl Popper in 1972 in which the Viennese philosopher juxtaposes (as Ligeti himself wrote) “exactly determined (“clocks”) versus global, statistically measurable (“clouds”) occurrences of nature. In my piece, however, the clocks and clouds are poetic images. The periodic, polyrhythmic sound-complexes melt into diffuse, liquid states and vice versa.”

Like much of the vocal writing done by Claude Vivier (whose traces here will be noticeable for fans of the Quebecois composer’s work) the twelve voices sing, according to the program notes, “in an imaginary language with a purely musical function.” And so spindly strings contrasted with the sheet-like vocals of ChorWerk Ruhr members, before roles reversed and chirping vocal lines were set against (and yet poetically with) steely-smooth strings. Benjamin held the tension between the worlds of voice and instrument with operatic grace, creating and recreating a sort of narrative with every passing note fading in and out as naturally as breathing. Interloping woodwinds and clarinets brought to mind the image of an Impressionist painting being projected in a darkened planetarium, against a backdrop of slow-moving galaxies. This was immensely moving performance, at once as emotional as it was intellectual.

Sir George Benjamin leads the Berlin Philharmonic at Musikfest Berlin (Photo: (c) Kai Bienert)

The audience was given a good chance to reset heart, mind, and ears between the Ligeti work and the final piece of the evening, Benjamin’s “Palimpsests”, written in 2002 and dedicated to Pierre Boulez (who also led its premiere). Another stage rearrangement (many were needed this evening) allowed for numerous basses at one side, a line of violinists at the front, and good numbers of brass, woodwinds, plus three percussionists directly in front of Benjamin. The set-up, compact but equally expansive, allowed Benjamin’s titular layers (and their related, possibility-laden connotations) to come in waves around and outwards and around once again, with clear references to the works of both Boulez as well as Olivier Messiaen, Benjamin’s former teacher. Expressive violin lines here act as a quasi-choir; at Saturday’s performance, there was a small but lovely moment between Concertmaster Daniel Stabrawa and violinist Luiz Filipe Coelho, in an almost-dancing lyrical duet which brought to mind Benjamin’s own edict that he wanted the piece to be “anti-romantic and yet passionate.”

Despite the sheer muscularity of sound particular to the Berlin Philharmonic violin section, Benjamin carefully controlled and shaped for maximum dramatic (and vocal) effect, placing just as much care on their twisting lines with harp, a highly cinematic and charged series of moments which recalled the sounds of film composer Bernard Herrmann. Impressively angry horn sounds were the loudest volume heard all night, complementing a stellar percussion section, whom Benjamin made sure to recognize during bows at the close. The gentle force which had opened the program now worked to close it, with clear indications of grace and elegance. In a current interview in New Yorker magazine, Benjamin noted that in his childhood “I loved playing the piano, but it was the orchestra I went to see […] I loved the variety of instruments, the energy, and the source of drama through sound.” That drama was realized in this concert – and then some.