Photo: Jimmy Donelan

Midway through our recent conversation, Thomas Hampson paused, trying to find the right word relating to a musical concept.

“You speak German, don’t you?”

He couldn’t see me, but I wanted to crawl under my desk with shame. Here I was speaking to one of the most celebrated living opera singers in history and my wall of Anglo-Canadian linguistic ignorance was as glaringly solid as ever. Hampson, ever the gentleman, patiently (dare I say enthusiastically) explained, expanded, and engaged, as is his custom in both life and in art.

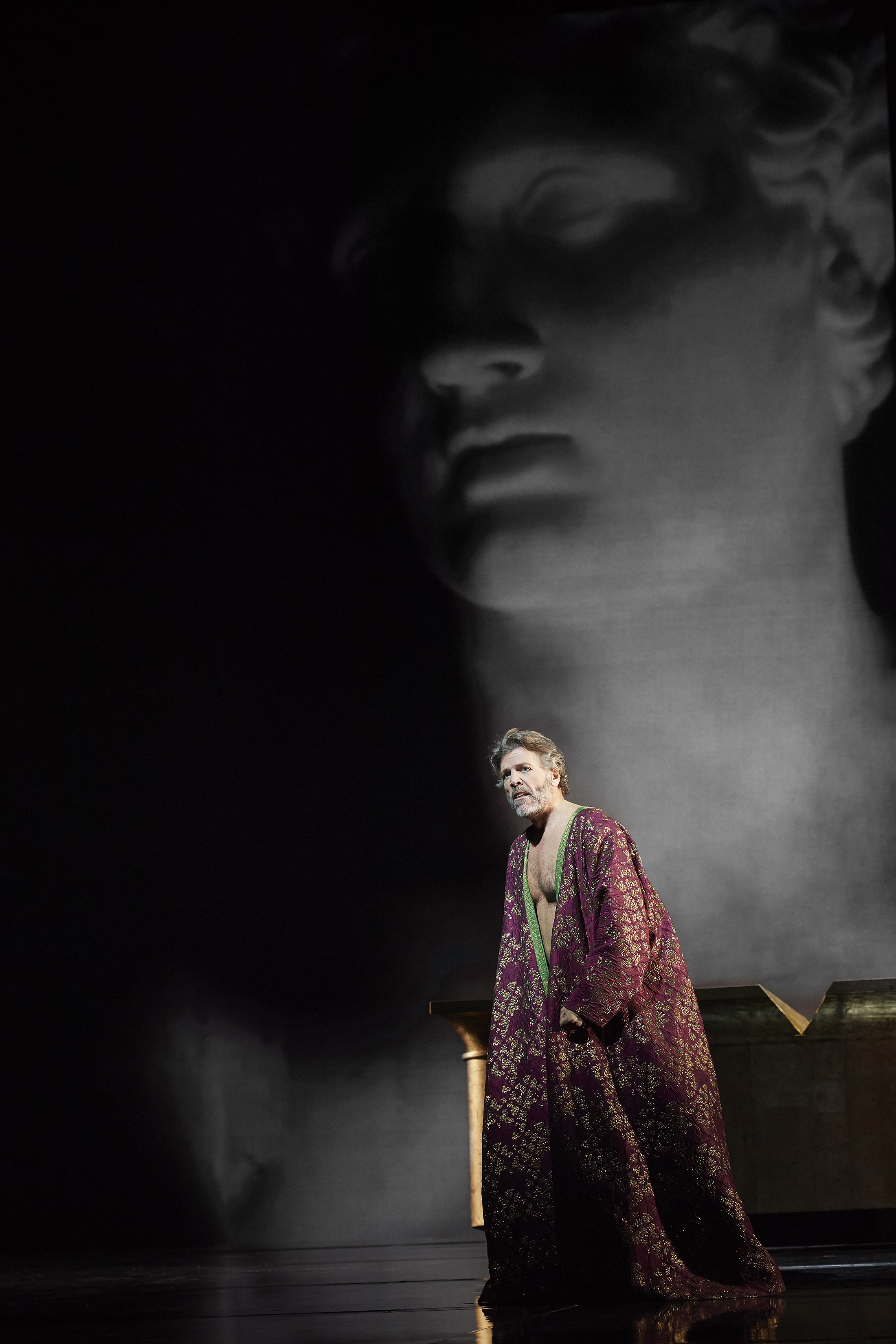

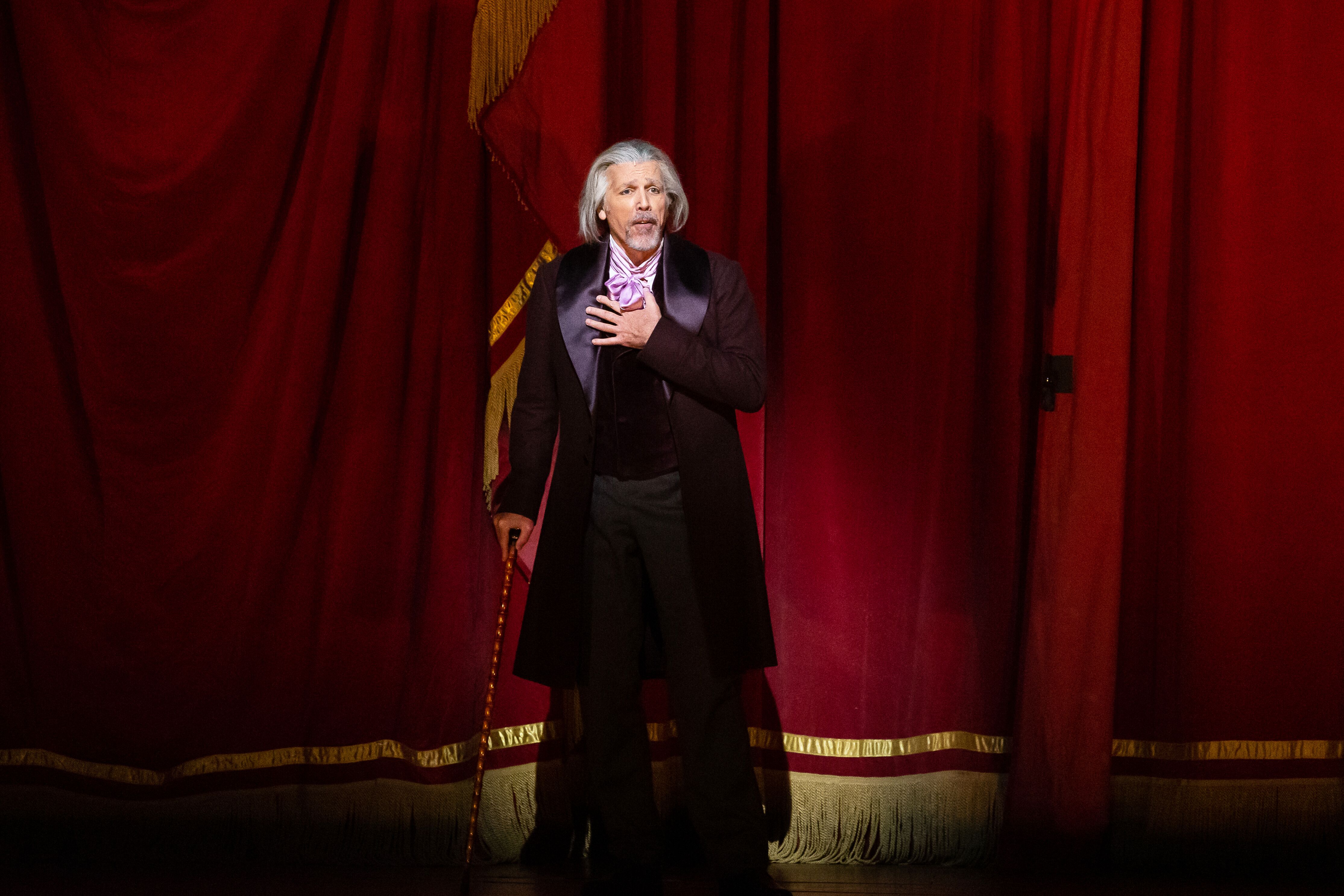

The American-born, Austria-living baritone is currently in Houston, having just opened The Phoenix by composer Tarik O’Regan and librettist John Caird, playing the role of the elder Lorenzo Da Ponte to bass baritone (and real-life son-in-law) Luca Pisaroni’s junior. The project marks the second world premiere Hampson has been part of this season alone, having performed as Hadrian in the Canadian Opera Company’s new work of the same name (by Rufus Wainwright) in October. With four decades of singing under his belt and engagements with every major house (Bayerische Staatsoper, Teatro Alla Scala, the Met, Wiener Staatsoper, Lyric Opera Chicago, Opéra National de Paris, Royal Opera Covent Garden, Salzburg), you’d think he’d be content to rest on his laurels — but as you’ll read, that isn’t who Thomas Hampson is. His voracious artistic curiosity often makes itself known, through keenly dramatic approach to his various roles (and they’ve included all the goodies: Don Giovanni, Scarpia, Eugene Onegin, Werther, Amfortas, Macbeth, Boccanegra, Figaro) as well as through his extensive recital work, albums dedicated to song, and intense teaching time. Dame Elizabeth Schwarzkopf, whom he met during his student days at Merola, once called him “the best singer in Europe.”

Thomas Hampson and director Peter Hinton in rehearsal for the Canadian Opera Company’s Hadrian, 2018. Photo: Gaetz Photography

It was at a performance at the Metropolitan Opera in 2017 when I fully understood and appreciated the true depth of Hampson’s artistry. Verdi being an absolute mainstay composer in my childhood household, I knew is works inside and out musically, and had heard many different version of many different roles, among them Giorgio Germont in La traviata. Despite the vocal grandeur of many performances, the reading of the role always, without fail, left me cold, whether on vinyl, compact disc, or live; the character seemed little more than a stiff cliche, barking on about honor and family. Hampson’s interpretation of the role in Willy Decker’s production, however, changed all that. Similar to my experience of Pisaroni’s Leporello in Salzburg in 2016, it was a bold, beautiful opening that made me rethink not only the opera and the composer, but my relationship with each, as with music and art. Hampson’s Germont was, by turns, angry, exhausted, overwhelmed, a deeply moving portrayal of a man in full awareness of his obsessive, possibly ill son, trying to balance his own sense of guilt with a seething fury echoing that of Alfredo (apple, meet tree). Hampson’s portrayal was just as much vocal as it was physical; his watchful, smart modulation and timbre were not meant to be pretty, graceful, smooth — all the things I’d grown up hearing. His Germont was, put simply, beautifully human, and it remains one of my all-time favorite performances on the stage to this day.

As Germont in La traviata, Metropolitan Opera, 2017. Photo: Marty Sohl

There’s a true and highly committed work ethic behind such performances, and it’s one Hampson has been recognized for often throughout his career. He has a load of honors to his credit: they include a Grammy for his role as Wolfram in a 2003 recording of Wagner’s Tannhäuser (done with Daniel Barenboim); six Grammy nominations; Male Singer of the Year at the 1994 International Classical Music Awards; five Dutch Edison Awards (including one for Lifetime Achievement); four Echo prizes; a Grand Prix du Disque, and many, many more. He has worked with so many great conductors (Leonard Bernstein, Antonio Pappano, Maris Jansons, Andris Nelsons, Christoph Eschenbach, Fabio Luisi, Kurt Masur, Zubin Mehta, Seiji Ozawa, Michael Tilson Thomas, and Franz Welser-Möst) and always has kept firm commitments to both to the art of song as well as to contemporary works; next season he performs the role of Jan Vermeer in Girl With The Pearl Earring (Stefan Wirth, 1975) at Opernhaus Zürich but before that, next month, he sings Mahler’s Rückert-Lieder, a work Hampson is known (and rightly celebrated) for.

Another famous thing Hampson does is concert tours with Pisaroni, playfully called No Tenors Allowed, which makes a stop at Toronto’s Koerner Hall this Tuesday (30 April). A mix of opera, operetta, and showtunes, the evening is a showcase of the baritone’s flexible vocality, theatrical vividness, and serious approach to his work. Even if he’s singing a Broadway number, it’s easily discernible just how much Hampson means every single word — and that applies just as much in conversation, in teaching, in rehearsal, in life, as it does in voice. Art and life fuse in a beautiful, passionate co-mingling with an artist such as he, and it’s that integration which, for me, powers his charisma, his artistic commitment, and that insatiable curiosity, which, as you will see, is such a palpable cornerstone to who he is, as artist and man.

Thomas Hampson as Hadrian in the Canadian Opera Company’s world premiere production of Hadrian, 2018. Photo: Michael Cooper

You have an immense artistic curiosity — what fuels that?

I’m just like that! How can I say this? In what I do, I’m a musician; my life and my mind as a musician is, every day, every hour, I’m exploring ways we express ourselves in a language we call music, and when that is coupled, especially in the song world, with the metaphor of our imagination through words, I find that it’s an incredible adventure into why we do what we do, who we are, how different people think of different things. That’s a grandiose answer to your question!

Something was written two years ago, or two hundred years ago, or twenty minutes ago, can, in some ways, not be the determining factor — it simply has been attempted. Of course, we to try and capture how people do what they do in a musical language. The story of Hadrian is fascinating, the story of Da Ponte is fascinating, the story of Scarpia is fascinating, the story of Boccanegra is fascinating, just to name some big characters; why do they do what they do and who are they? Some have a bit more to do with the value of humanity and the value of life, but to know a Scarpia is to understand how desperate and tyrannical humans can be to one another — and how dangerous humans can be. Tosca is just as contemporary today as the day it was written. These are things that fascinate me.

In terms of specifically new music, I feel very strongly that new opera must be supported — that sounds like more of a drudge that I mean it, but we have to give our composers the chance to become great. Verdi’s first three or four operas were not exactly amazing but they showed an amazing potential, and they’re probably all worth some kind of performance. There’s an awful lot of pressure on new opera productions today because people come, sit there and fold their arms and say, “Okay, am I going to experience greatness?” But I think that’s missing the point completely. Are we engaged in human beings? That’s my question and certainly, we were with Hadrian and certainly we are here with The Phoenix.

Thomas Hampson as Lorenzo Da Ponte in The Phoenix, Houston Grand Opera, 2019. Photo: Lynn Lane

What does that give you then, as an artist?

Everything.

A lot of people in your position would be content to rest on their considerable laurels.

That’s not who I am or who we are as musicians. Bernard Haitink doesn’t keep conducting at 90 because he is trying to stay employed and wants to remember who he is. This what we do in the morning, this is what we live for, it’s our lifeblood, whether we play for three or 3000 is not the point — it’s what gets us motivated, what motivates us in terms of being musicians. It’s not about a gold watch and 30 years service.

Teaching at the Manhattan School of Music. Photo: Brian Hatton

Does that feed into your teaching work? Chen Reiss said in a recent conversation that teaching gives her a lot as an artist.

Yes, and It gives me a great deal too. I’ve taught a lot in the last 25 years — I’ve learned a lot about it over the years and I’m thankful. When I teach for a couple days, or walk into a masterclass, just having to articulate the fundamentals or rearticulate the whys and wherefores to young colleagues, somehow reinforces your own; it’s like giving yourself a voice lesson. I thank my colleagues for letting me take the time to give myself a voice lesson! Now that I’m more extensively involved in pedagogical activities, and planning them, I see it as a wonderfully healthy way to pass it on. I’ve had some wonderful instruction since the heydey of my career — I was very fortunate; they gave me inroads into how to study and how to prepare that have stood me well. I’m confident that, at the very least, I can be a help to my younger colleagues in an experiential way, so I can say, for instance, “That’s not a path you want to go down.” In the last five or seven years, in my more concentrated studies, I’m very active in keeping abreast to pedagogical thought and to keeping it simple, and helping young colleagues truly mature into young professionals. It’s a passing-it-on situation, and it gives me a great deal of energy. To be part of someone else’s “a-ha!” moment is very intoxicating.

Keeping that “a-ha!” moment in mind, you’ve worked with some great conductors, and continue to. How much do you still find yourself surprised at learning from them? Everybody has a different style, different personality, different ways of adjusting.

That’s a good question. When I was singing a great deal of Mozart, bouncing between Harnoncourt, Muti and Levine, that was, talk about different styles and personalities! Everyone is on the same mountain, the mountain is the clarity of human emotion in musical language, and the different glaciers you might be on have different challenges. Yes, you do not sing, in a phraseology sense, the same with a Muti as with a Harnoncourt, but those are not absolutes. Both of those men are deeply dedicated, experienced musicians, and great conductors don’t happen by accident — they’re some of the greatest musicians musical minds. The best conductors have a direct and kind of uncanny ability to initiate other peoples’ making of music in a collective way, and that’s an extremely important talent. To learn from these really wonderful musicians is a privilege; having someone like Jansons feel you are the one he needs to make that musical decision or choice of repertoire viable at that particular concert, it’s a great validation. For him to want to do that with you is great — I don’t feel so engaged by him as invited to participate because we can go to this or that level with this or that piece, and that’s very important. Michael Tilson Thomas — I’ve learned so much from him, he’s so damn smart. I don’t have the musical training these people do, or the musical talent; I have a musicality and an instinct that can keep up! Bruno Walter said that about Lotte Lehmann; she was an amazing singer, she moved people enormously and was a great pedagogue, but he wrote the forward to her book, “Lotte’s curiosity has always informed her instinctual knowledge.” I think that’s a wonderful thing.

Photo: Mark McDonald

That relates to your dedication to lieder and the art of song — it seems like another symbol for your artistic curiosity. Why song, why now?

That’s a wonderful question. I’m not into a particular fach, or niche repertoire. I’m not trying to help keep the song alive because I think it’s a “cool” thing. As humans with have two options to express ourselves: we can either verbally articulate it, or we can write it. Whether that’s in a hieroglyphic or a scratch on a cave wall, or a fine use of the language any one person would call their own language, it doesn’t matter — the point is to get the experience, the emotional and intellectual experience out of your head and leave it like a footprint in the sand, and say, “Okay, this is what I thought.” Poetry has a little bit more focus to that in that someone is deciding in a particular linguistic structure to express thought and emotion at the same time. This is a wonderful source of inspiration for people whose antenna is essentially musical; these two antennae are somehow trying to figure out a way to articulate what Copland said, the moment of being alive now. And the composer fleshes out, in a musical language, more the emotional context of what that poem is about as well as participating in the intellectual side of the narrative, and that’s to think about what this or that chord represents, this or that harmonic structure or harmonic rhythm, whatever the tools of that musical composer are which indicate they’re fleshing out what they perceive that poem was about.

That’s what I feel is the alpha-omega of singing. This is what we do: we make the human experience audible, in a language called music, inspired by words, which is for the purpose of us as a community experiencing that particular moment of humanness, if you will. And I don’t think that’s a hobby, I don’t think that’s a fach, I don’t think that’s genre; I think that’s the beginning and the end of everything we do as singers, period. The idea there’s a concert fach and a lieder fach and an oper fach, “he’s this or that type of baritone” — I just think that’s a very dangerous and un-useful thing to think for singers within their own particular development.

Also, it’s not an idea to give our audiences, that we are jobbing. I think the arts and humanities is far more important than the idea that “Oh, it’s a job.” It is more than that. What we provide in the evening, what a classical concert is about, if you will, is the privilege and pleasure of any human to stop the clock just for a second. It might be three minutes or a forty-minute movement; we stop the clock for the privilege of going inside and asking ourselves, as listeners and performers, who are we? Why are we here? What does this all mean? How can we make a way forwards from this experience ? If that’s not the thrust of the classical music industry, the privilege and pleasure and the inroads of audiences we provide for their own human living development and experience, we’re in a lot of trouble. You can’t market or brand that. It has to be understood as part of the process of us asking, how can we be better human beings?

Operetta gala in Baden-Baden with Annette Dasch, Piotr Beczala, and Pavel Baleff conducting the Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Photo: Michael Bode

Stopping the clock doesn’t have to be limited to serious music, either. As Barrie Kosky and I discussed last year, it can happen in operettas, a genre you perform in and make part of your concerts.

It’s like making fun of opera plots — talk about low-hanging fruit! But I don’t think opera is about plot; I think opera is about dilemma. Whether the door was opened or the sun went up or five years passed or whatever, it all gets condensed —the point is that a trio of people might come together to explore who they are. When the composers are gifted and the language of character is so apparent in their music — i.e. Verdi, i.e. Mozart – then I think we all go home happy. If you take that in another way, to the operetta world, yes they’re simpler but why not? The thing about operetta that fascinates me, as well as musical theatre, is that the distance between emotional language and the language of the music so much closer. And the believability factor is instantaneous with an operetta; If they don’t believe every word, you’re dead, forget about it. If you feel for a minute it’s about you and your voice, they’ll walk away. That’s not quite true in opera. It’s an experiential dimension, a wonder of what’s happening as much as why. It’s all healthy, and part of the enriching human experience of the theatre and the power of the musical language.

But we have a completely different sensibility to the language of music than the era from which a lot of these pieces were written; Bellini is not Mozart, Verdi is not Mozart, Puccini is not Verdi. I think these questions are important. As an example, Verdi, as great as he was, was vociferously criticized for the vulgarity of the beginning of Otello when he wrote it. I don’t know any conductor, esp Italian, who don’t feel the mantle of Verdi’s spirit on their shoulders. Yet all of the instruments are different — the strings are steel, the clarinets are plastic — the decibel possible out of an orchestra pit in a house now is something people in Verdi’s time would have never experienced, let alone the sheer size of the houses now. What am I trying to say? I’m saying when we do these performances, we need to be sensitive to the context in which they were performed; a forte piano in Schubert is different than a forte piano in Stravinsky I don’t care who wants to disagree with me — it’s just different. As musicians. it’s our job to flesh out the reality, to make it audible, so that the experience is contemporary, regardless of when the piece was written.

As Scarpia in Tosca at Bayerische Staatsoper. Photo: Bayerische Staatsoper / Wilfried Hösl

Part of what makes your performances so visceral is that you are such a believable stage presence. Luca and I spoke about how he prefers being known as a singing actor over being known for just his voice alone.

I know he’s said that before, and he’s right. What I would like is to be remembered as somebody you believed when you saw or heard him in the theatre. “Whether a Winterreise or in an opera or in recital, Hampson always made audible that which he was singing.” Luca’s right — in the theatre context, in an opera context, I certainly want to be thought of as a thoroughly professional singer; I don’t think that’s different than being believable in an acting sense. I think what makes Luca special is that his believability factor is so high. He searches for that dimension of understanding of why the music is saying that, and incorporates making it physical as well as audible.

A lot of my colleagues are extremely preoccupied with being remembered as a special or unique or great voice. I mean, Callas was unique in her generation, unique in several generations, with records that are still selling — people want to listen. Why? It’s not just the amazing agility and color and timbre. It’s the believability factor, giving it up to music — I believe what I do on stage has, this is going to sound incongruous, but it ain’t about Tom Hampson, it’s about what Tom Hampson can do to make that which he’s singing audible, believable, inhabitable, for the people who are experiencing that performance. Now, does that mean it’s not about me? Of course not. It’s my abilities to do that, but my whole effort is about the Schubert moment ,the Mahler moment, the Verdi moment, the Wainwright moment, the O’Regan moment.

In concert at Ingram Hall at the Blair School of Music. Photo: Vanderbilt University/Steve Green)

Those moments have to be infused with authenticity.

Yes, you have to do your homework. You have to work to do that. it’s a tremendous amount of study and detailed sensitivity. People who talk about the spontaneousness of this or that performer onstage simply don’t understand the dimensions of performing. Of course we want to be thought of as spontaneous, there’s nothing more miraculous than someone saying, “It sounded as if he was composing it as he sang it!” That’s one of the greatest compliments, but that is only possible with the minutest, most detailed sensitivity and homework.

And sometimes it’s nice to experience artists where you can see the gears turning, you can feel them, you can smell them. I love that.

Yes! I must say, I am not preoccupied with what people think about me. I’m preoccupied what what I think about me. It’s one of the things I talk about with my young colleagues: if you go onstage like a golden retriever, wanting people to like you and think you’re the cutest dog ever, you’re going to be a nervous wreck. I am not concerned with what people think about the Winterreise when I sing it; I am concerned that I achieve what I believe Schubert was trying to achieve in that cycle. I cannot convince anybody of anything from the stage. The energy in a concert hall or opera house is not from the stage to the audience, it is from the audience to the stage. And if you embrace that, and you know your technique and you know why you’re standing there and go into your zone as quickly as you can in that public context, as a performer your nerves will be more controllable. If you go out thinking the applause-o-meter is important, or “Oh God, there’s blank faces in the first few rows” … I mean, I don’t know who’s in front of me; I don’t want to know. That’s not why I’m there.

Photo: Catherine Pisaroni

There’s a real intimacy with singing — you don’t have an instrument; it’s just you, your body, the space, and sometimes conductor or accompanists, and the music. There’s something vulnerable about that.

Yes, for sure.

It’s a real pity when you see singers who’ve lost that vulnerability.

Yes, that’s so true — and their sense of wonder. I do this piece called Letters from Lincoln by Michael Daugherty, and it ends with him signing a letter,”Yours very sincerely, Abraham Lincoln.” I mean… wow. You have to sing it a few times not to get emotional.

The German phrase “stehen für” means “represent” but it doesn’t quite grasp things— it means someone who stands in place of someone else. That’s what I feel like when I sing the great music I’m allowed to sing; I am there at their service. The only megastars are the composers and poets, in my opinion. I know Pavarotti felt the same way. We all come and go. You do the best you can. My responsibility is a final link to the greatness of thought and captured in a language called music.

Photo: Jiyang Chen

And that includes fun music.

Yes, there’s different constellations. With the concert performances, yes it’s clever, we’re family, “no tenors allowed” — that’s a total tongue-in-cheek joke, it has no validity to our tenor colleagues or anybody else, it’s just a smirk and a hahaha. What is in these programs is Mozart. Bellini, Verdi, Massenet, then we get into Lehar, Kalman, Cole Porter, Gershwin, and our last encore is Donizetti’s Don Pasquale, which is the precursor to Verdi. This is great music, these are great moments — admittedly some are lighter, but audiences will take this roller coaster ride, from a Don Giovanni duet, which is brief but white-heat kind of stuff, to this enormous contemplation of freedom and self-determination with that Don Carlo duet, to ending with “Anything You Can Do, I Can Do Better”. I defy you to put a brand on that evening. It is interesting, some of the reactions we get, but audiences get it completely, they go with us. Most people respect who we are but some have had to chew on this: what is it? A vanity evening?

“That isn’t real opera!”

Yes, and I think that’s missing the point of a duet evening, this bouquet of great musical moments of human experience. Is it the Winterreise? No. Is it Don Carlo? No.

Wolfsburg concert. Photo: Andreas Greiner-Nap / Soli Deo Gloria

But it doesn’t have to be.

Exactly! Something in the back of ours minds is, maybe it’s the first time some of our public is introduced to some of this great work. We could’ve programmed nothing but duets — I did a record with Sam, I love duet evenings, I’ll do one with Opolais and another Gheorghiu this year. I think it’s a big evening, it demands everything from Luca and I — it is not a walk in the park. We are out there on the line, but we believe the program is very user-friendly and has a lot of value as well a big enjoyment factor for all of us. I want to believe some of that snobbery is because I’ve not had a chance to talk to the naysayers and offer a different perspective.

Maybe No Tenors Allowed in itself already offers that perspective?

That’s what our hope is!

9 Pingbacks