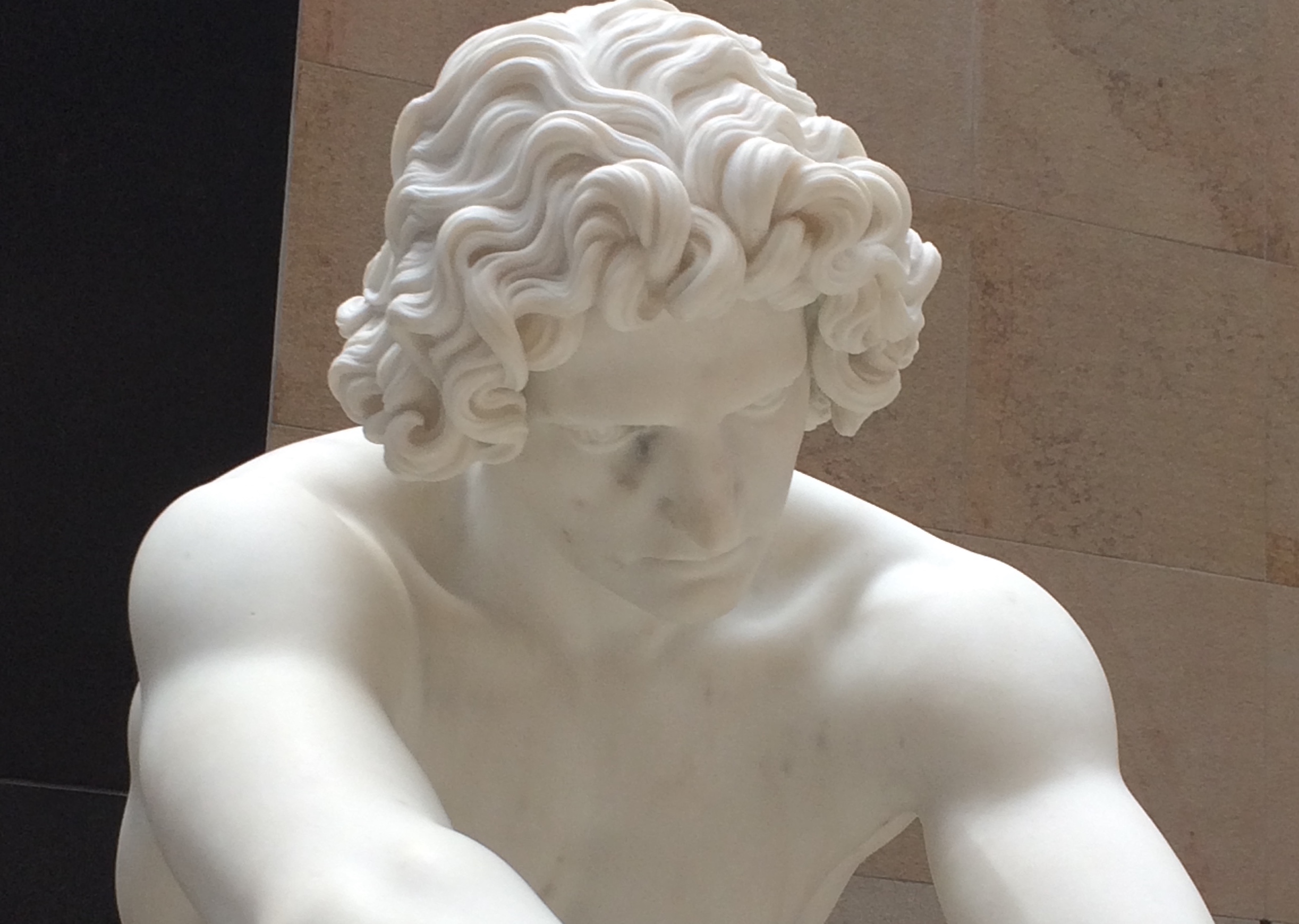

A scene from the 2013 production of Puccini’s Manon Lescaut at La Monnaie / De Munt, directed by Mariusz Treliński, set design by Boris Kudlicka. Photo © Forster.

This essay started out as a love letter to fashion, within the context of the joys to be had in buying a dress amidst pandemic. Folded into this were contemplations on dressing up – for the opera, and otherwise; there were (are) quotes from Susan Sontag, Oscar Wilde, and Marlene Dietrich. I still intend to publish this essay in some form or another in future (hopefully sooner than later), but for now, it feels smarter, especially in light of the restart of live cultural events as autumn draws near, to explore my original idea, one I was encouraged to pursue by a longtime editor friend. It’s been in my mind to write this for a while, and the combination of seeing a production of Puccini’s Manon Lescaut recently, a closet full of pinned items, an overstuffed drawer of underthings I’ve come to despise, all seemed like cosmic signs urging me on.

Following my second jab in August I had an exchange with this individual which touched on issues of body image, fashion, fit, popular perceptions, and the longtime, frequently tortuous relationship I have with my body, and more specifically, my breasts. This time last year I arranged an appointment with a doctor to see about a reduction, a procedure I had long pondered. To relieve the near-constant shoulder and neck pain; to have the stacks of ribs, distorted by years of intense weight, corrected; to have things finally, at long last… fit… it seems, even now, like a distant and incredible dream. To have a breast reduction would (could) mean I might at last look like the actually-size-2 woman I am, that I might actually for the first time in my life, be in proper proportion without the aid of acres of close-fitting fabrics. I wouldn’t have to worry about stares, smirks, or judgement; I could wear what I like – a low-cut gown at the opera; a fitted turtleneck in the classroom; my strapless sundress in the supermarket. Ultimately I decided against the operation – for now. The thought of removing chunks of my own flesh, of living with permanent scarring on a part of my body to which I have an already-troubled relationship, of navigating postoperative pain, of courting judgement (and possibly real horror) from would-be lovers at the sight of my scarred body… such concerns created a mountain of anxiety I am not, even now, able to scale. So I contend with thick straps, well-padded cups, tight, strong bands; a good bra really is a piece of marvelous engineering, and a well-fitting one is something I will pay (have paid) good money for. Finding one that fits off the rack is (like any item of clothing) a rarity; I have a litany of bras sitting in a drawer, all of them impaled with pins in a desperate attempt to fit a much-shrunken frame (I have lost a significant amount of weight over the past eight months or so). It’s good enough for now, but oh, for the freedom of awakening without pain, of moving around without aches, of fitting things perfectly, of never having another button pull or another visible strap or of having to buy things two sizes too large. Oh, to never have to feel I am inviting lecherous stares, acrid judgment, social ostracizing, or risking professional advancement, credibility, acceptance, approval.

It’s an odd thing, to write a piece which might come off as a complaint, when one admittedly receives attention, and more specifically certain types of attention, over the very thing (things) one purports to dislike. I do get a jolt of joy from the reactions I elicit through my highly-curated posts; it bolsters the shaky confidence of an isolated woman whilst reassuring some form of public worth, however superficial. That satisfaction is finite (perhaps intentionally so), as I wonder why in hell I can’t seem to get over 100 likes on anything, all the while knowing the reason: algorithms don’t favour aging female bodies, or faces, unless scantily-clad and heavily-filtered – since wrinkles, cellulite, stretch marks (more precisely, real, lived experience) are unwanted within fantasy landscape celebrated and promoted throughout much social media, Instagram in particular. A thusly-filtered photo of me in a bikini, bum expectantly up, breasts prominently displayed, head orgasmically thrown back, ultra-posed, ultra-horny, ultra-algorithm-pleasing, would unquestionably hit that magical 100 (200? 400? 700?)-likes mark. Indeed, such measurement (of worth / goodness / hotness / popularity / desirability, and much else, maybe) is an unfortunate tool in the freelance world, one worth knowing how to wield, if requiring very careful handling. Post the wrong (so-called) things, and one is ignored, along with one’s work and oeuvre; post the right (so-called) things, and one’s work is read (my own analytics bear this out) but one courts judgement in the process, along with distinct and narrow forms of categorization. One risks judgment and labels as well: dumb, shallow, vain, needy, an attention-whore, wannabe, poser, super-bitch. Bimbo. Dilettante. Sycophant.

All of these labels (and worse) run through my head whenever I post anything imagistic; I often wish there was a “reduce giant boobs” filter that might lessen such anxieties, but then I wonder if it’s really me who has the problem(s). My mother certainly didn’t think so. Years ago she and I attended the opening night of an opera season; it turned out to be her final one. A night of dressing up was a blessed bit of relief between chemotherapy sessions and hospital runs, and she looked so pleased and proud as watched me descend the stairs of our house wearing a black, strapless Yves Saint Laurent vintage piece (found in a consignment shop for a song), a dress that fit perfectly. I knew there would be hate-filled stares entering the members’ lounge – those always greeted me, they were predictable, if very wearing; I was good at pretending such nastiness didn’t bother me; I still am. “I love how you scoop your hair up and put your shoulders back and stick your bust out and don’t care what anyone thinks,” she said later that night. I didn’t have to look at the faces in the lounge to actually feel their all-too-clear judgments; I threw my head back indeed, jutted chin out, batted eyelashes, gave a tremendous smile. It’s a skill I have come to perfect. To quote Marquise de Merteuil (from Christopher Hampton’s Dangerous Liaisons; play 1985, film 1988), “I learned how to look cheerful while under the table I stuck a fork onto the back of my hand.” Add to that making a tremendous middle finger.

There exists in my closet a lovely line of beautiful gowns, one a sumptuous, sweeping, super-low-backed, very fitted number, ordered in a fit of restlessness amidst the worst of the pandemic last year. I slipped it on at New Year’s in an attempt to summon some needed optimism. “If I ever have the nerve to wear this publicly,” I thought, “at least I’ll know what’s required.” (Two rolls of tape, carefully applied, and even more carefully removed; I will use more if and when that time ever comes.) But dare I court the inevitable judgment if I wear it? Dare I risk dumping whatever little professional credibility I might have (and have fought for), all for the sake of my innate love of fashion, and an even more innate need to feel the joy of wearing something that actually fits, and amidst (sigh, post) pandemic times, when dressing up is a pleasure that has been so long denied? I think, to a certain extent, many women, especially us large-breasted ones, are raised to ignore, to carry on, to try to keep head held high (when our necks and shoulders aren’t screaming in agony), and to fight against the high tides of judgement while riding the big, bouncy waves of attention. The digital era has brought a keen awareness of the pressures of playing to desire, of its inherently performative nature, of the idea of “sexy” being somehow divorced from presence (in the symbolic sense), of the lines between fantasy and reality blurring, of the perceived “power” in playing to a male-gaze-y algorithm that dictates what is seen, when, how, by whom. Susan Sontag wrote, in a 1999 essay “A photograph is not an opinion. Or is it?” (published in Women (Random House, 1999), a book of photography by Annie Leibovitz) thusly:

To be feminine, in one commonly felt definition, is to be attractive, or to do one’s best to be attractive; to attract. (As being masculine is being strong.) While it is perfectly possible to defy this imperative, it is not possible for any woman to be unaware of it. As it is thought a weakness in a man to care a great deal about how he looks, it is a moral fault in a woman not to care “enough.” Women are judged by their appearance as men are not, and women are punished more than men are by the changes brought about by aging. Ideals of appearance such as youthfulness and slimness are in large part now created and enforced by photographic images. And, of course, a primary interest in having photographs of well-known beauties to look at over the years is seeing just how well or badly they negotiate the shame of aging.

As an aging albeit large-chested woman with a chosen online presence – one I require and have cultivated as a freelance writer and educator within a particularly narrow cultural field – I am simultaneously aware of both the judgement and the attention, the inherent risk of professional punishment, and virtue-patrolling, to say nothing of professional discreditation and social ostracization, all of which run concomitant with potential benefits and possible advancement. (Whether that advancement manifests in actual dollars and opportunities remains to be seen, and various classical and academic ingenues might tell you something similar, however quietly.) Damned if you do; damned if you don’t; such has always been the case for women, and never more so than now, in the pandemic-ridden 21st century, whence a screen is professional, social, political, cultural, creative, and personal, all in one. My mother’s pre-boomer, always-wear-lipstick generation didn’t have to face this, but then, if she had, I’d suspect she’d be very popular.

My mother had a ballet dancer’s body: a long torso, long legs, just-right shoulders, a long neck, and perfectly (to me) small hips/bum/breasts. She had my ideal body shape, one I still covet and dream of having. Anything else, to my mind and literal body), is chubby, gross, vulgar. She was a “model” in the definition that still largely fuels the definition of Very Beautiful today. “You didn’t get those from me,” she’d say, staring at my chest. Shorter, fleshier women have a history of being placed into the tiresome bin labelled “curvaceous” (or the like), one that is wholly fantasy-driven and easy to discredit; she always used the word “voluptuous” as a compliment, but it never felt like one. I could never (and indeed cannot) find things that properly fit. While I’d watch my thin, small-breasted school friends go off and meet decent men, I always felt I’d been left with horny ones wanting naught but masturbatory entertainment. The work world was just as bad, if not worse. An early episode of the American television sitcom Three’s Company (1977-1984) features a large-breasted if wholly unqualified woman promoted over the more small-breasted Janet by a bug-eyed man in a cheap suit who speaks in a lusty rasp. The woman later visits Janet at her apartment, resigning in a fit of shame and exasperation, and explains the realities of navigating a world in which men only see breasts (and their related sexual desires) without seeing the attached whole person. “They say things like, “why don’t you stand over me and keep the rain off, baby!”” she says, holding back tears.

These days of course, that woman would have a huge Instagram following, post pictures of herself in tiny bikinis, call herself “empowered” and many would simply seal-clap along. I’m not so sure; to borrow from Charles Laughton’s character in the 1957 film Witness For The Prosecution, that line of thinking feels “too neat, too tidy, and altogether too symmetrical…” (Note: most breasts are not, in fact, symmetrical, let alone sitting at attention when one lies on one’s back; they tend to sloppily nod off to armpits, gravity being the great downer in all senses.) Swimwear always presents a challenge; modest is realistic if boring, but finding something that fits is impossible. I don’t own a bikini, and if I did, I wouldn’t wear it publicly, let alone post pictures of myself in it. “Be proud!” shout the masses, “do your thing!” The problem is, all the male things go up whenever I reveal too much tit in public, and though i can’t control the reactions, I hate that I inspired them at all, and find myself wishing, at such moments, after a galling incident or smutty, unwished-for attention, that I had those perfect, tiny, pert, ballet-dancer breasts. The scars, the pain, the thought of going into a hospital at all right now… tell me to sit, round-shouldered, and do another round of dreary sit-ups. Apparently strong abs are helpful, but they’ve yet to relieve an ounce of the pain.

Following my second vaccination, I came home and changed into a low-backed bodysuit, one I would never wear in public – too revealing, too honest, too real. (I love it.) ‘Real breasts versus fantasy ones’ is a distinction that needs to be made (one might say this about female bodies overall) – I consciously thought this, putting that bodysuit on – but the need to recognize that distinction points more directly at a need to acknowledge real people versus fantasy figures. A 2013 production of Manon Lescaut from Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie (Brussels), directed by Mariusz Treliński and featuring Eva-Maria Westbroek in the title role, caught my attention for just this reason. How refreshing, to see the soprano floppy-haired and braless and perspiration-soaked in the last act; yes, it’s the character, and yes it’s the opera, and of course, it’s part of the setting, but this was not the highly-stylized, romantic, dewy-doe-eyed suffering so often seen on opera stages. The transformation felt real, raw, and very visceral; it dared to explode the sexy-babe mythos into a thousand pieces, and dared its audience to see what was left. I wondered about two things, concurrently, as it concluded: Westbroek’s corseting (or apparent lack thereof, which is brave, and shouldn’t be, and yet) and, what would my opera-loving, glamour-obsessed mother make of it. In her younger years she so much resembled the younger Manon, poised and smiling across numerous images in photo albums spanning many decades. One shot features her wearing a green polka-dot bikini; she used to like to tell people how much she weighed when it was taken, some ridiculously low number, hiding the actual truth of her self-starving then, her utter self-loathing in fact, dating someone who eventually threw her over, having treated her like a diversion, a bit of fantasy, a sex doll. She wasn’t “curvy”; she didn’t have large breasts. I remember meeting him years ago, before she passed, wondering at her being so reserved around him then; I don’t wonder now.

And so I look at my closet-fulls of dresses, some of them my mother’s, many of them, like my underthings, full of pins and awaiting the skilled touch of my ever-patient tailor, and I wonder if I’ll ever wear any of them again. Do I want to? Dare I? Can I be floppy-haired, braless Manon and still have any worth? Still ignite any true desire? Does it matter? Can I be busty, non-music-degree-holding Catherine and still be perceived with any seriousness? Should I feel okay with being reduced? Am I not already? Oh, how I long for a good fit. A trip to the moon, even for a few hours, would not be so bad either; my shoulders, like much else, could use the rest. Maybe this is the season to fly, to not feel small, to not shrink, but to jut chin out, pull shoulders back, and at last, to truly smile, even, as the times dictate, it will be behind a mask or two.